Chicago's Concept-Based Group Exhibitions Show Strength in Numbers

Art Slant / Oct 20, 2015 / by Stephanie Cristello / Go to Original

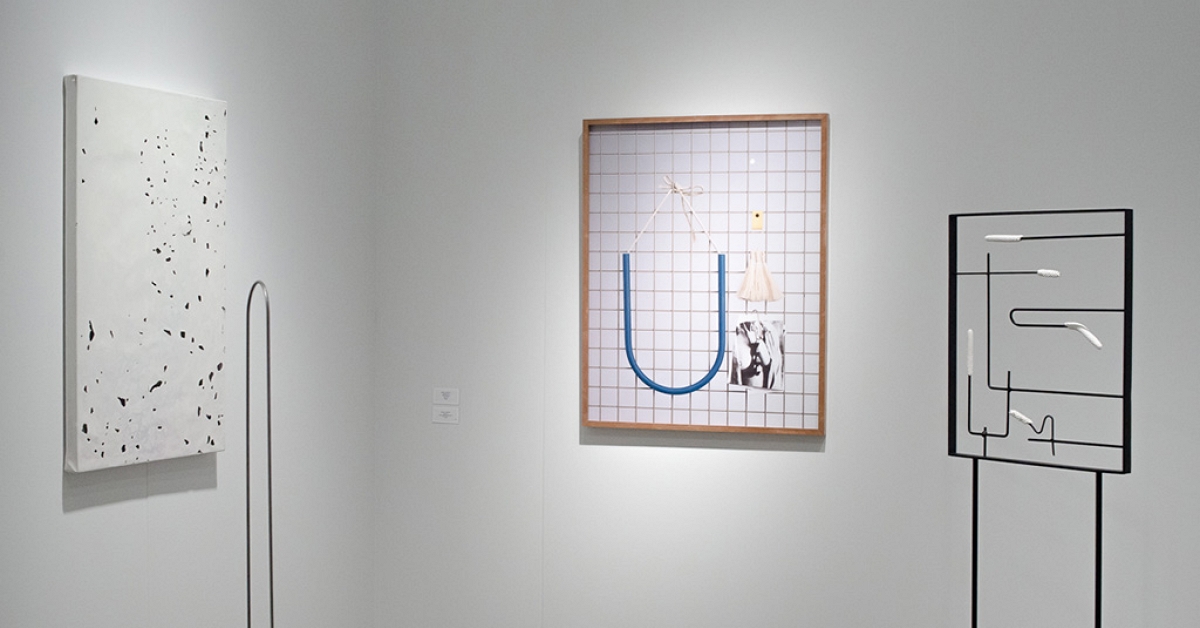

Theory of Forms at Patron Gallery

We start, fittingly, with Theory of Forms, currently on view at Patron Gallery—a new space headed by Emanuel Aguilar and Julia Fischbach, former Directors at Kavi Gupta Gallery. The Platonic nod in the title, while it certainly applies to the work on view—a collection of painting and objects that employ trompe l’oeil, material malapropisms, and other challenges to the paradigm between the shapes works take versus the concepts they propose—is also done on a very basic level of the exhibition itself. Theory of Forms is aware of its status as a group show. Curatorially, it strikes every chord, featuring 11 artists under the broad guise of including work that challenges reality. This of course is a wide field, yet the view of the exhibition remains focused and steady, reaching a balance between quotational references to art history and the optical function of the work. The installation is economical and straightforward, relating small to medium-scale pieces to one another in an airy and buoyant manner that could leave the seasoned viewer wanting for something more extravagant. But this exhibition is a slow burn, and what it lacks in the awe-inspiring multiplicity and grand gesture of an installation such as Rosenkranz’s, it rewards with closer looking. It is well worth the effort.

One of the first pieces the viewer encounters is a painting of the sea by Daniel G. Baird, a two-sided picture encased in a glass vitrine. The treatment of the surface is photographic, its other face material—covered in a texture of sand. The mechanism of the installation combines the image and the potential experience of the sea to make a whole that is never viewable at once. Here, it stays suspended in separation. As in other works in the exhibition, there are a series of clues within the image or the form that indicate a mediated experience. This is not a space for the singular; the singular no longer exists in an image-based world. In the age of integrated networks, one has to challenge Plato: while we can accept that yes, reality is the shifting entity, constantly changing through perception and context, how different are our ‘ideals’?

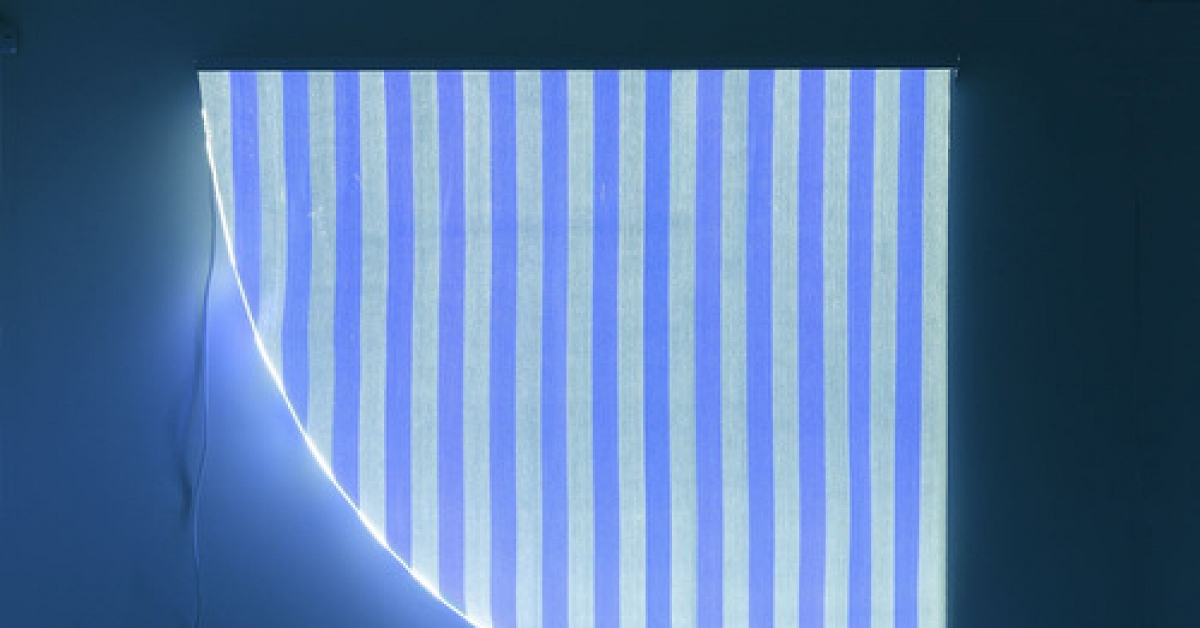

In the second gallery, a collection of paintings by Mika Horibuchi lines the wall, mirroring the composition of playing cards. Instead of diamonds and hearts there are soft and voluminous snow-white peaches, peaking out from a wall of crisp green leaves, gently rendered to achieve a level of sameness on the surface of the painting. Textually, these paintings are “read,” ushering with them a string of aphorisms whose echoes lightly hum in the viewer’s ears: luck of the draw; painting the roses red; wild card; follow suit; she has it in spades. These words, of course, are fantasies, but serve to underscore the paintings’ otherwise anxious relationship to the concept of tranquility—while the images seem serene and entirely convincing, their form places them in jeopardy. Horibuchi sets us up; our chips are all in, but what are we playing for?