PATRON is pleased to present Partings, Swaying to the Moon, a solo exhibition with Brooklyn-based artist Kaveri Raina. The exhibition will open with a reception for the artist on Saturday, February 29th and will continue through May 30, 2020.

Partings, Swaying to the Moon

Kaveri Raina in conversation with Sangram Majumdar

I first came across Kaveri Raina’s work while she was an undergraduate at the Maryland Institute College of Art. Since then her work has developed immensely. In 2018, soon after she moved to New York from Chicago, I stopped by Kaveri’s studio while she was a resident at the Triangle Arts residency in Dumbo. The paintings on burlap and the graphite drawings on paper initiated a conversation around the body, abstraction, the immigrant narrative and the poetics of language. Recently we picked up the conversation as she prepared for her exhibition at Patron Gallery in Chicago.

Kaveri Raina: More recently, I am constantly going to my notebook to find a word. And then the word helps me navigate through the painting. It’s a new thing. It helps me associate it to a feeling or a meeting.

Sangram Majumdar: The verb “to hover”, is a really specific verb specific to existing, but also a type of movement that is within a very narrow spatial location. I think about “hover” simultaneously with hummingbirds and helicopters. What is it about that verb or that phrase that has been so generative for you?

KR: It started in the summer of 2017. I was writing a lot, and then this word struck me - hovering. So I started giving myself some questions like what does it mean to hover, what does it mean to be suspended, what does it mean to be held, what does it mean to hold someone. But hovering as a concept was something that I was constantly thinking about. Even if I have to go, for example, to my studio, which requires going from here to there, I know I have to do that, because we all know what we have to do—but the mind loves to wander and that space of wandering to me is hovering.

I feel like I’m constantly in this lull, like I’m constantly suspended. I don’t think I always see it as a negative. But hovering can have a negative connotation. I don’t even know if it’s not knowing; I think sometimes I am just waiting. As you said, the helicopter, they’re waiting for the clear signal. But I don’t know if there’s a signal. I don’t know what I’m waiting for, but it’s this constant la-laa- laaaa. It’s just that I don’t know what I’m doing. But even though I will do what I’m doing to get to a point, I think I’m constantly in this stage of … distinctive wandering.

SM: Do you think part of that is a way of withholding judgment, of acknowledging and accepting and taking in what’s around you and really waiting before you insert your own ego, your own biases, into the mix?

KR: Yeah. I think it’s a lot of we’re filled with uncertainty on a daily basis. I think hovering could also perhaps mean this idea of just working with what I’ve been given in a way. Just like before the phone call with you I was talking with this friend of mine, and we were chatting about having grudges. I was like, “I think I still have this grudge for not being able to decide at the age of 10 or 11 to have the freedom of just staying where I was and not moving.” We were talking about our parents. And I said, “I’m really close to my parents and my family and all of that.” But this idea of not being able to choose at that age.

When you bring this up, yeah, things just happen; we go with the flow because you kind of have to lead a life. It’s kind of like this mutual, “Do I go here? Do I go there? Or do I just stay in between?” So yeah, I think it has to do a lot with just doing what you’re given. Of course, I choose a lot of things. I choose to paint. I choose to write. I choose to eat. But I think there’s the fundamental thing that I still feel was like I didn’t have the freedom to choose at that age that this is my life. Because I always think about what life would’ve been, and that doesn’t go anywhere. But I still think about it, I guess.

SM: Well, that’s interesting you’re talking about this because maybe we talked about this in terms of a shared narrative. I was 12 when I moved, and I am always fascinated by classic questions that immigrants get, such as, “What was it like to move?” It’s a strange question because I’m being asked to pass judgment on a choice I didn’t have.

I feel like there are really two types of forms in your paintings, the closed shape and the porous shape, and sometimes there are linear components. But they all really resist naming. They stay in a type of metaphoric existence. It never feels like any of the forms want to be anything other than what they are. This gives them their actual autonomy in reality and particularity. It’s the insistence of their nature that makes them believable.

KR: Right. I definitely like the open-endedness. Of course, we can kind of place it. It’s good if you can say, “Oh, it’s a lemon,” but sometimes you can also say, “Oh, it’s kind of an orange.” I don’t like the idea of forcing my thoughts in any way. For me, I’m painting my thoughts and my feelings and all that. But for the audience, I very much like it to be open as much as it can be for interpretation and for the idea of being generous—about having a lot of forms, having more than less is what I think about a lot too.

Even when I have a show or something, thinking about it as a dinner party or something where everything is kind of hung, and someone comes in, they’re like, “Okay, this is a lemon.” And then someone looks at the painting and they’re like, “Oh, this is like a stream of water.” Having variations of emotions, feelings, experiences is what makes a dinner party engaging. I strive to make that happen at my exhibition as well. I think people coming into the space and relating to the work is really important to me. Things could have multiple identities, multiple personalities, and can be fluid in that sense.

SM: When you say open-endedness it’s a way of presenting information that stops before it becomes dogmatic or didactic. You’re letting the viewer complete the thought or make it into what they want. In a way, you’re respecting the viewer, respecting the person at the other end of the table, if you take the analogy of the dinner table.

KR: Exactly. And it’s funny because someone said this to me relatively recently. We were just talking about life in general, and then the paintings came up too, and they mentioned, “I find ambiguity particularly frustrating,” and I said, “Well, actually, I’m giving you a lot with these paintings.”

I think people want to know so much. Specificity is huge … they want to know, “Is this a lemon? Is this a leaf? Is this a person crying?” I think people crave specificity. A lot of these figures and forms, the more open-ended they are the more ambiguous they are. But it’s weird because for me they’re also very particular, but how they’re translated become this figure that’s very general in a way, that this figure is laying down but don’t know if there’s a pillow there if this is a man or a woman. They’re not very gender specific either. For me, you fill in your own experience. When you look at this, you envision what you want to envision. I don’t like the idea of telling you my particular, specific story.

SM: Kaveri, do you think your threshold for this indeterminacy or liminality is greater because of how you participate in the world and your own personal biography?

KR: You’re asking if my biography, my narrative, my upbringing, and all of that, situations that I was put in, if that is in a way, the uncertainty or in between-ness reflected in the work?

SM: Yeah. If you feel like that gives you a certain familiarity.

KR: I think a lot of it has to do with my reservations of societal pressures and norms. I think I’m constantly thinking about how I behave with my parents versus my sister versus my best friend, and how no one really knows me fully, and how I have to change my behavior according to people that I’m presented with.

SM: Right.

KR: Of course, we never know ourselves to the fullest. I don’t think I’m even fully aware of who I am. It is a process. There’s a lot of uncertainty and questioning that’s continuously happening. Honestly, I’ve been trying to embrace this unknown and embrace uncertainty. I think that’s why I am drawn to particular words like hovering. I think that helps me be more grounded because then I relate that word to these feelings of lull, these feelings of uncertainty. I think that helps me to be more specific for myself in the paintings, the words.

There isn’t a huge secret or anything that I am trying to hide, but I think there’s some sort of reservation I have, and I think that’s why the paintings have this layer of open endedness because I worry at times that if it becomes too specific for the audience then I’m revealing too much. But sometimes subconsciously you reveal things you don’t even know. I don’t think I’ve ever done that yet in a painting where I subconsciously say, “Oh, I’m going to let it out and just paint,” up to this point. Maybe I will in the future. I don’t know, perhaps.

I am interested in the idea of being secretive and coded. Through paintings—I’m trying to figure something out, I guess, through each and every stroke, each and every painting, and then putting it out in the world. But I don’t think that’s selfish. But a sense of secrecy is alive. It’s contradictory. Of course, there’s something secret about things that I’m trying to reveal because I’m putting them on the surface and the viewer sees them. I’m welcoming, but I’m also not giving them all the information. There is so much to see for you to make your own picture of it, in a way. Somehow, they still feel generous.

SM: Yes, definitely. Something I wanted to talk to you about, and I think this touches on it, has to do with creating a space through your artwork that allows the view in. You’re not telling a specific story. These are not illustrations that accompany text. The paintings need to somehow pull the viewer in and keep the viewer connected.

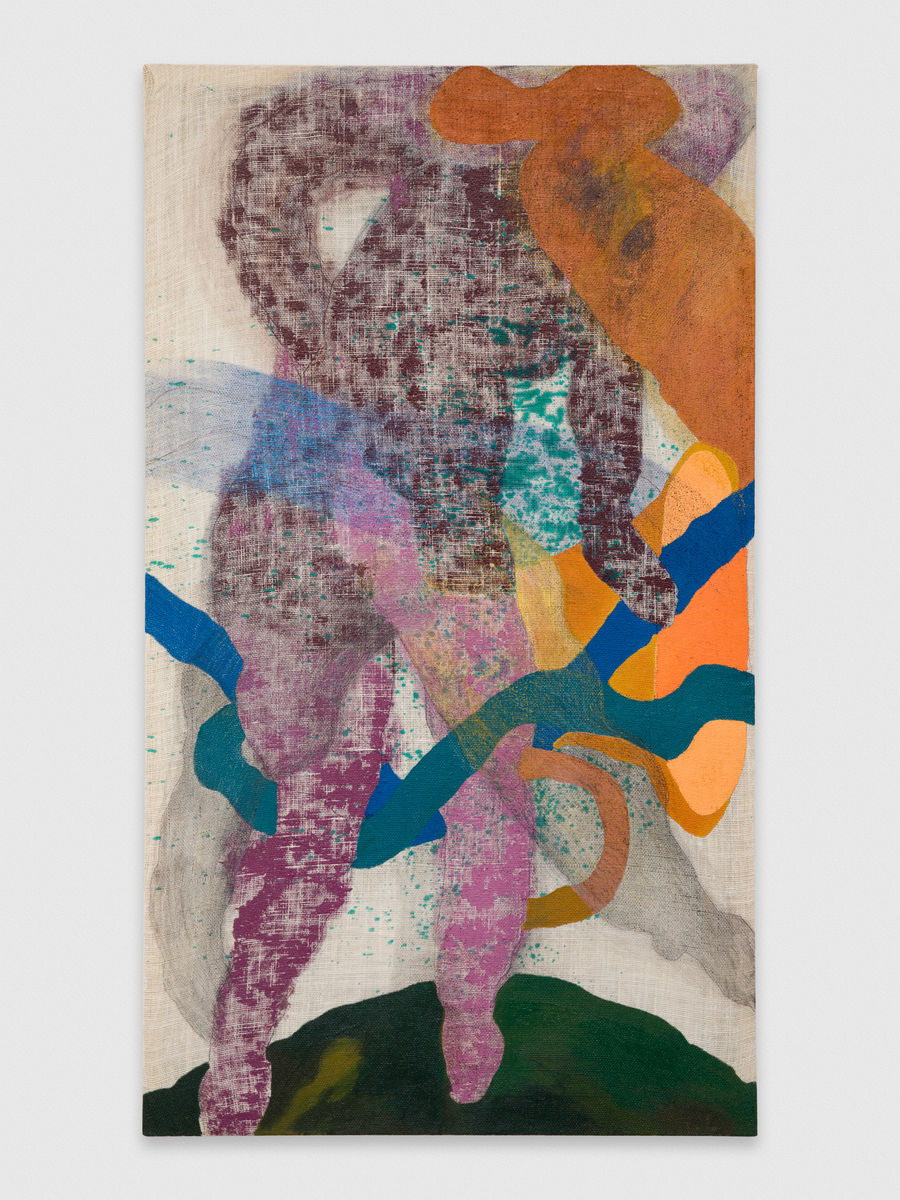

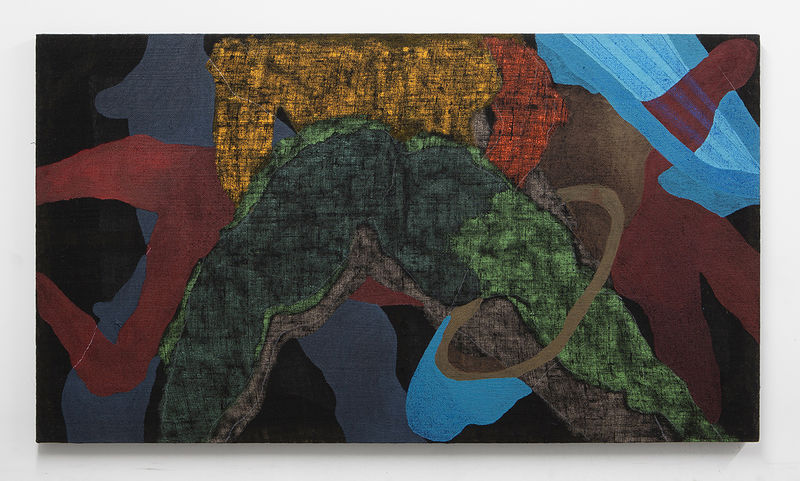

If I look at the ways you build the painting, there seems to be multiple decisions that happen that simultaneously acknowledge a space that is behind the surface, but at the same time keeping you engaged with the surface. So whether it’s a silhouetted form that’s really rich in color, or that we become aware that there’s paint on the back of the open weave burlap, or the third being that we see a form and realize it’s something we can’t really name, I find myself constantly moving.

You seem to be constantly telling us that the surface is important, but it’s not the full story. The surface is the invitation, the greeting, the announcement that tells us that we’re invited to this place of action.

KR: Right. There’s this constant push and pull. There’s front and back. I’m really hoping the viewer, even if they’re not a painter, can feel that the sense of location is really important, where the paint is coming from. Is it the back? Is it the front? Is it the side? I think sense of place, sense of location makes it even more important for me. The act of lingering, I’ve been doing that more. And the more you sit with something, I think time plays a huge role in things too, of course. Sometimes after knowing someone for five days, I feel like I’ve known them for such a long time. Also, sometimes you know a person for five years, but sometimes you can’t even get to know them fully. But through painting, I guess the hope is that it makes it you’re just wanting to look at it to a point where they create their own narratives.

I know I’m not trying to force my idea of anything because I’ve already done that. I’m putting the painting up because I’m happy with it and I’m satisfied, content. And it’s now doing the job of hopefully the viewer can enter it in a different way, not my way, because there is no way to enter it my way. For me, it doesn’t make sense to make it specific. Even if it’s specific, I don’t like the idea of hitting it over the head, “It has to be this way,” because I don’t believe in convincing beyond a point. I think seeing my idea, thought, emotion, experience in a painting is something that I’m more interested in. Hence, abstraction, a love for abstraction.

SM: I have to say, it’s difficult for me to look at your paintings as purely abstract.

KR: Totally.

SM: I know this has come up, and people have talked about your work in that way, that they’re abstract, and to the degree that Elizabeth Murray’s paintings are abstract. I did want to ask you, or create a space for you to talk about something a little different if you’re interested. There is always an impulse from the writer’s standpoint to contextualize an artist’s works by creating a biographical framework. I’m curious how much of that framing, whether it’s as an immigrant, whether it’s coming from a specific cultural background, how much of that do you feel you want to own, that you want to acknowledge, and where do you feel like there’s a slippage and that you feel disconnected with?

KR: I have some sort of a close relationship with all the people that have written on my work. The most recent being Megha Ralapati. I’ve known her for three or four years now. She’s a close friend, and although she is not an artist, she is a curator, art historian, and also works at an art center. Her text is the most personal—because she’s known me in a more in-depth, more personal way. I think how she describes a lot of the paintings, like Le Mon to Hover, ominous figure from before, limbs set off in the distance, etc. I love the fact she mentioned the Kaveri river and the importance of that. Very poetic and touching for me. She mentioned about the 1.5 generation, I thought that was really great because I feel that I’m constantly looking above at what’s happening in a way. I like how she delves into identity in that way. And then she talks about these are not really abstract paintings and continues to talk about other artists like Francisco Clemente too. I think I do relate to her text very much.

SM: I agree. One thing in speaking of that text, I was curious what do you think about her reference to the Sanskrit term neti, neti, that loosely translates to “neither that nor this”. As soon as I read that, I was thinking of kind of a broad cultural gesture that most Southeast Asians are familiar with, which is the head shake.

KR: Right, right. You never know what they mean.

SM: Right. It could mean yes, no, or maybe. And to me that’s a great visual analogy of a form that hovers, to return to that verb.

KR: Right. I didn’t even think about that. That’s so true. Growing up with that, I think seeing my parents behave that way too like, “Do you want this? Do you want that,” but a lot of things never got discussed. What is that phrase, putting things under the rug? I don’t know. It’s just like putting things off, and then you don’t acknowledge it, and then it becomes awkward when you don’t acknowledge it. So yeah, I think that phrase neti, neti is really great and the head shake you’re talking about, because I think that’s just culturally very much so true in my family. We all know what we want and what the other person wants but this idea of not conveying fully or admitting fully.

SM: It’s like a level of familiarity that is beyond naming, right? If I make a jump visually to your paintings, the forms in your paintings are very clear; they’re very acknowledged. They have a clear sense of boundary in color and shape and presence spatially within the logic of a painting or a two-dimensional space. But I can’t imagine them having a formal name or phrase.

KR: I am trying to be realistic about a lot of things and trying to see for how things are and embracing what I have, and not even naming particularly what I do have. I think since I’ve lived in New York for almost two years now, I think about the light in my studio a lot. So much. I have grown to enjoy painting in the morning, getting up in the mornings. I used to be a late-night painter, and now I’ve shifted to getting up quite early and spending the whole day with natural light.

SM: If you don’t me jumping in, do you feel like it has a little bit to do with living within your means or working with what you have, which is not necessarily a negation of drive or ambition, but about making the most of what is given to you?

KR: Yeah. I think about that a lot. I also think about how I wouldn’t have been a painter or an artist if I wasn’t in India. I can’t think of anything else that I would be rather doing. I think that makes me feel content. A big part of the move to the States was that I found out I love art, painting in particular. I didn’t choose to be an artist for money or fame. I know that I have a love for it and the fact that I enjoy doing it and I’m somewhat content with it so I’m going to continue doing it.

Ӭ

It gives me great satisfaction, and it gives me this level of content that I purely enjoy.

SM: What is it inside yourself that you feel solid about that makes you do this day in and day out?

KR: I’ve had many jobs, but I haven’t had a job that I have fully been engaged in. I’ve worked at a grocery store, as a deli clerk, at a call center, I’ve worked as a photographer at a zoo, and museums. Amongst all of these jobs, nothing is as meaningful as painting. I was just sitting in my studio the other day and I called up my father and said “I think despite everything that I still want, right now I feel this basic feeling of being content. I have the luxury of being in this studio with this giant window and light.

And I’m actually painting at 2:00 PM.” I just felt like I was extremely lucky in that moment that I could actually do what I like, which is painting and being in the studio.

I think at this point, and the fact that I’m making a living out of it is something that I didn’t think that I would be able to do even after going to undergrad and MFA and all of that. Even moving to New York and living here for almost two years, it just seems surreal. And a lot of artists do this. I’m not the only one who’s doing it. I have a lot of friends who’ve lived here for 10+ years. Success comes and goes. But when you do it yourself and you’re going through this journey and emotion, I didn’t think that I was going to be able to sustain or live in a city and be able to paint. I think just the daily act of painting is something. Of course I can keep painting and just be better and better at it as time goes. But I think just the idea of just even being able to do what I’m doing, I think it’s pretty big. Because coming from a family of no art background, but my family embracing it and learning so much about art now and all of that. It’s of course a very non- traditional route. That’s why also I just feel like this is in a way given to me, even if it’s something I chose, which I did. But I don’t know if I would be able to pursue it if my family didn’t support me. But I also feel like I have to make the best use of this time, best use of the studio. That’s why I also think that it’s given to me, but this is what it is. There’s nothing else to do other than paint.

SM: Let’s talk about a couple paintings. One is called DT: Reminiscence, Will I Be Missed and then the other one is Squinting While Fading, I Became. They’re both like internal dialogues. In the first one there’s a yearning. And then there is also a potential for that hope to not be followed through. In the second painting, both verbs ‘squinting’ and ‘fading’ refer to a form of disillusionment, something literally going away that is meaningful, perhaps an image, perhaps something that is meant to be maintained. But the result being ‘I became’ suggests a formation on one end and a formlessness on the other.

KR: It’s really good how you describe the titles. I really like that.

SM: Thank you. I think they’re great. I think they really capture a type of confluence. The image of an old, hand-held balance comes to mind. You put this little weight on one side, and you put something else on the other; you’re just keeping things in balance. I feel like your paintings are very much about this type of balancing on a very high-wire balancing act of just how much on one end will help balance, which to me is different than a formal. To me, it’s more of a felt experience.

KR: Yeah, it’s definitely a feeling.

SM: And I love how feeling is so tied in the writing, in the color, in the way how the paintings are made.

KR: I think that’s where the words come from. Honestly, where there are lived experiences or things that I have actually felt or experienced in real life or have wanted things and haven’t happened yet or maybe won’t happen or anything. They’re all very much an extension of me basically. For example, Squinting while Fading is an actual feeling I have a lot. I have slowly started to think about what it means to sway. Referencing the title for the exhibition, Partings, Swaying to the Moon. Swaying is not as negative as hovering. The idea of swaying feels more poetic and more resolved in a way and I think coming to terms with who you are in a way. Here in this last painting, Squinting While Fading, I Became this idea of still being constantly overwhelmed, constantly not knowing what you’re doing, but this idea of trying and trying and eventually, hopefully there is a knowing, a result. It’s also a real feeling of when you’re trying to squint with your eyes. There’s a point where you’re trying to be clear, but in a way, that idea of squinting actually makes me dizzy.

SM: I didn’t think of it this way, but even with the act of “squinting while fading”, if a person is fading the assumption is that they have no control over it; they’re fading away. But squinting is something they have control over. They’re working really hard to make the world blurry while they themselves are becoming blurry, which is what they have no control over. It’s a strange use of energy, right? Squinting is a bit like hovering in the way that a lot of energy is expended to maintain an experience or to retain a phenomenon that is not necessarily about image clarity.

I like when you’re talking about that you’re swaying, it introduces the idea also of play. When I think of swaying, I’m thinking of somebody on a swing and they’re moving back and forth and there is a space that begins to get activated that is between two poles, between the high and the low. Perhaps maybe a parallel could be poles of whether it’s abstraction or representation, whether it’s the figure in the landscape, whether it’s chromatic, really strong color and really muted color, the different poles that exist in image worlds. That feels very playful, and I think it acknowledges a certain type of rigor, but also experimentation, which I recognized when I came to your studio. It seems you are constantly drawing, that you’re constantly putting things on paper, revisiting the same image motif, and seeing what can come out of it.

KR: Right. When I think of hover or hovering it’s this fast-paced motion because I’m very anxious and I’m constantly a restless soul— no matter, coffee, no coffee, tea, I’m jittery, full body jitters constantly. I think that’s what I think about restlessness and hovering. And then I think slowly I’m trying to enter in this realm of swaying. I was thinking the other day, because when I paint, I’m standing a lot and moving things, but I did this movement— when you’re looking at something for a while. I did this motion where I was still of course on my feet, but just movement from left to right was happening. And I started thinking of this word ‘swaying.’ What it means to sway.

When I thought about the title, Partings, Swaying to the Moon—somehow the moon just came to my mind while I was painting. I was even thinking about Bollywood music videos because they’re constantly running around trees. There are a lot of love songs in which they are swaying, just constantly swaying around each other. But the characters in the movie, in the videos, they want something. This yearning. I am assuming love. Ha! They want a life of fulfillment?

You mentioned playful—it is a good word. But embracing journeys, embracing the restlessness, but being also calm and peaceful about it in a way. We’re all multi-faceted, and we all have those different variations of ourselves. But the sense of calm I think is what I was thinking about when I was thinking of swaying to the moon and just staring at the ground. You stare at the sky, and the idea of what it could be, of what life can be, I think is something that I’m kind of moving the word towards in a way. I think Squinting While Fading is this potential figure somehow becoming something while moving in this upward motion.

What I’m trying to say is swaying is perhaps the next chapter. Or like a buildup on hovering, more encouraging in a way. A lot of people come to the studio and we talk about hovering and what it means to hover, and I think it gets overshadowed by sad memories or past and all of that. I think there’s so much more than just being always talking about sadness or things that you couldn’t get or things that you don’t have or what you could have meant or people you could have been with or something like that. I think constantly thinking about what could have been because I think I was thinking about that for such a long time that it’s not really helpful.

SM: Or healthy, yeah.

KR: I think there’s this shift in perception that things are what they are, what you do to better them, and whatever better means for you. But how do you sway them to a point where it’s more encouraging and not dependent on a moment from the past or something?

SM: It’s just really exciting to see somebody making paintings that are meant to be experienced. What I love about them is that they really feel like a story or a song; they feel like they exist in time. That to me is very exciting. I love that I can’t really describe the paintings any one way, that language fails in trying to describe your paintings.

KR: Which is weird because I feel like words have been so helpful recently. But I like that it doesn’t necessarily translate into that specific verbiage or that word that I’m thinking. It’s more of an experience or a feeling than the person or the viewer experiences, instead of it being very specific. That’s kind of where I’m headed. Because I feel like there’s only so much you can go on based on intuition.

SM: Your titles are a lot like your paintings in that they carve out an area. I’m looking at the yellow painting In An Area Of Grey, Out In An Area Of Grey. So, in and out, and out, in, and the repetition of an area of gray. When in fact there’s no gray in the painting. So gray is not a color space; it’s a metaphoric space. It’s a psychological space.

The more we spend time with the painting, it begins to parse out a zone just the way the forms create an arena. I think there’s a great parallel relationship between visual and the written language, even in the way the forms are not fully anything, but yet they’re full. Just like if I think of the word gray, it is so contextual, whether in terms of color theory or in a sociological sense. It’s really amazing the way the body is suggested, whether it’s a long format like the blue burlap painting, which evokes the shape of a reclining body, or the slightly more vertical paintings that have somewhat of a portraiture format. I love those slight hints of the body through format, through material, through color, through touch. These are exciting, and in person they’re even more beautiful.

KR:Thank you. Yeah. I like that you noticed the grey one. I’ve been thinking about that phrase a lot, in an area of gray, out of an area of gray. I think going back to spiraling, wandering, hovering— the frustration of not knowing something specifically. Because in a way, what’s the point of doing things if there isn’t an intent, or a sense of achievement? It’s constantly going in this area of unknown. And if you’re going to come out in an area of unknown, where does that lead you in a way? It’s a cycle, right? We repeat back and forth. Perhaps there is a progression, but there’s no way of measuring that progression if we don’t learn from those spirals. We keep on doing this over and over. I appreciate all you’ve said. It’s good to hear what you think and process these emotions.

Sangram Majumdar is a painter and a Professor in Painting at Maryland Institute College of Art. He lives and works in Baltimore, MD.

Critics’ Picks: Kaveri Raina

Artforum

May 30, 2020

May 30, 2020