“If every human death entails an irrevocable absence, what can we say of this other absence that continues as a sort of abstract presence, like the obstinate denial of the absence we know to be final? That was the missing circle in Dante’s Inferno, and the supposed rulers of my country, among others, have taken upon themselves the task of creating and populating it.”–Julio Cortázar, “Denial of oblivion,” introduction to the 1981 Paris Colloquium against the policy of enforced disappearances in Argentina.

For the anthropologist Michael Taussig, the inscription of Latin American political history into social landscapes has frequently outlined a space of death that has a long and rich culture, “where the social imagination has populated its metamorphosing images of evil and the underworld.” As a consequence of imperial politics and colonial exploitation, the space of death is a heterotopian expanse where terrestrial beings and supernatural creatures live, die and are reborn. It is also where, as suggested by Argentinian writer Julio Cortázar, a “missing circle” in Dante’s inferno prevails, one that was created and populated by our ruling classes.

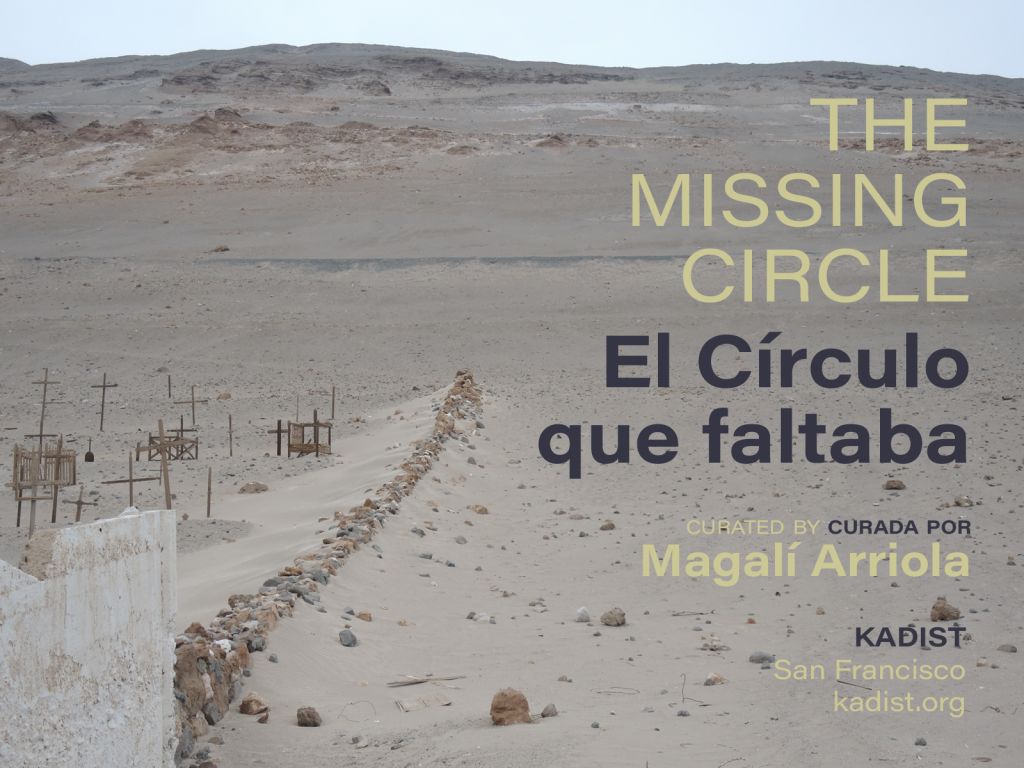

Adapted from its large-scale iterations at the Museo de Arte Moderno de Medellín and the Museo Amparo in Puebla, the exhibition The Missing Circle at KADIST San Francisco departs from the shared experience of death, extinction, and its various manifestations that have permeated Latin America and the Caribbean since colonial times. The figure of the undead has embodied early capitalist slave economies such as the exploitation of the Brazilian gold miners, the Black slave labor that sustained the US cotton plantations, the endlessly toiling Haitian zombies in sugar plantations, and the forced labor of Indigenous people at Colombian rubber plantations or Mexican henequen ranches. Effigies of the desaparecidos (the missing) have incarnated the victims of military dictatorships, guerrillas, and civil wars in Guatemala, Paraguay, Chile, Peru, or Argentina for a large part of the twentieth century. And, more recently, the haunting bodies of the undead have appeared as the lost souls of those fallen to drug wars that countries such as Mexico or Colombia have waged on their own citizens.

Like a fable providing an allegorical approach to the Latin American social landscape, The Missing Circle revisits particular episodes in the region’s political history to explore the role that counted corpses and unaccounted souls play in the world of the living. These latter take part not only as casualties of institutionalized violence and bare life, but also as the emancipating agents at the heart of new political formations. In other words, the dead without bodies and the bodies without life that not only haunt our memories of the past but also linger in our expectations for the future.

By convening historical individuals, fictional characters, tangible facts, and mythical stories, The Missing Circle draws a space in which temporary markers acquire a different morphology, and reveals the connective pathways between facts and places, objects and subjects, witnesses and narrators, and actants and spectators. Yet, rather than aspiring to unearth truth or fabricate fiction, the resulting narrative addresses the politics of interpreting and representing facts in what Taussig refers to as “the social being of truth.”

Image courtesy of Museo Amparo.