Jennie C. Jones: New Compositions, installation view. Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, Patron Gallery. © Jennie C. Jones.

Jennie C. Jones: New Compositions, Alexander Gray Associates, 510 West Twenty-Sixth Street, New York City, through October 23, 2021

• • •

On its face, the title of Jennie C. Jones’s exhibition at Alexander Gray Associates, New Compositions, is decidedly innocuous—the kind of moniker that nearly seems a placeholder. But, in fact, the artist’s choice of the ostensibly neutral composition is quietly telling in the context of her practice: the word is used often enough in visual art with respect to form, yet plays a singular, defining role within the discipline of music. And it is around the surreptitious potential of such a double life, openly proposed by Jones’s works but easily overlooked, that her practice revolves.

Indeed, for decades, she has made abstract “compositions” that initiate a taut dialogue between the fields of visual art and music. The zips and planes of her wall-mounted pieces steeped in geometric abstraction immediately articulate the optics of Minimalism. Yet those paintings’ material abstraction (and structuralist specificity)—comprising as it usually does not only monochromatic canvas but also affixed panels of acoustic foam—points to musical performance or, more broadly, sound. In this way, she suggests an artistic tradition that occludes the eye, opening another front on which to address art. Indeed, over the years, Jones has plainly expressed her aspiration for the history of music and specifically jazz (the genre most explicitly explored in her audio works) to provide her an entryway into that of Minimalism. By invoking sound to recast the latter in different perspective, she engages and infiltrates the legacy of a movement predominantly associated with the endeavors of a handful of white male artists and lays out a new set of coordinates and possibilities.

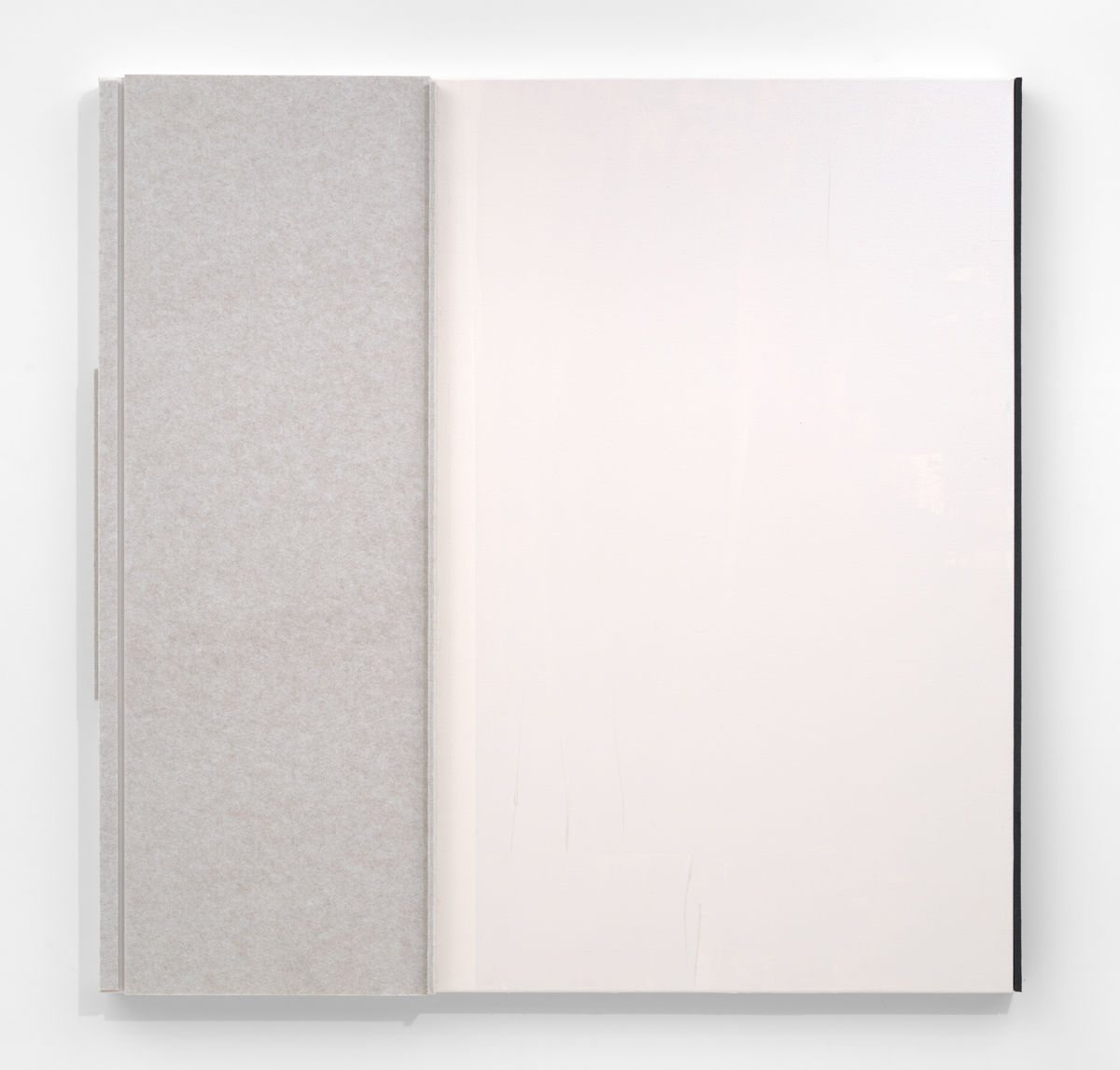

Jennie C. Jones, Soft, End, Measure, 2021. Architectural felt and acrylic on canvas, 48 × 48 × 3 inches. Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, Patron Gallery. © Jennie C. Jones.

The technique that propels this counterpoint of sound and vision seems straightforward enough. But even within the vocabularies of visual art, the theoretical implications of Jones’s approach defy any such ostensible simplicity, proving instead to be provocative and expansive. For example, Jones has continually made a subtle yet crucial turn on Minimalism’s critical tropes around theatricality (whereby the viewer’s presence “completes” the work). The acoustic foam she deploys in her wall pieces—beyond citing the discipline of music—is by design oriented around the shaping and control of sound’s timbre or, more plainly said, the quality of sound’s reverberations within a room. This attention to sonic materiality underscores how her painting might address an individual viewer, but only while calling out other (unseen, unnoticed, or taken for granted) material terms of the surroundings. In the artist’s current exhibition, such attention to space is made all the clearer as Jones has now—in addition to her longtime usage of acoustic foam—introduced architectural felt designed to dampen environmental noise. (Felt in an art context will also prompt thoughts about interactions in social space, given its unavoidable reference to Joseph Beuys.)

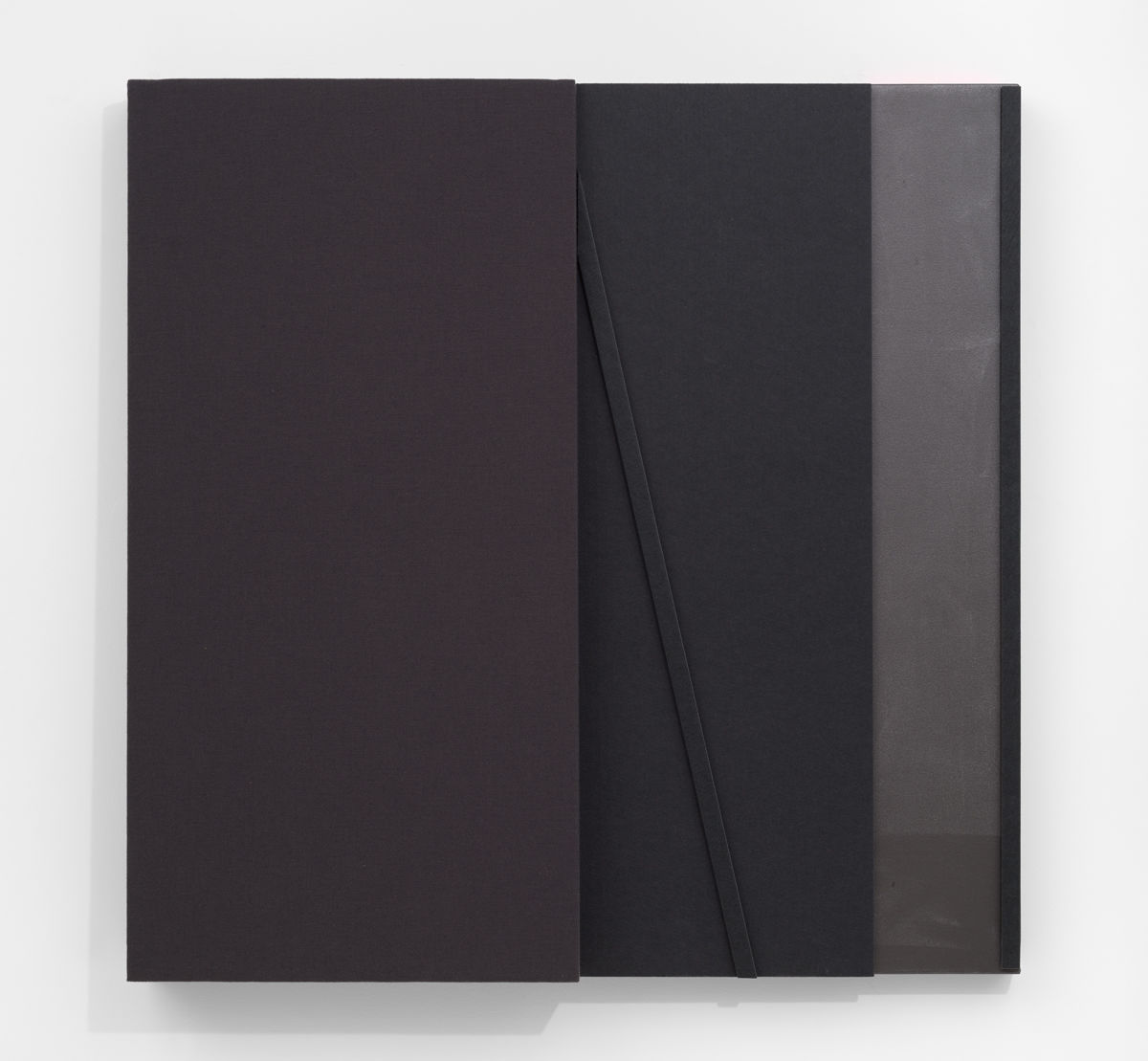

Jennie C. Jones, Fractured Extension, 2021. Acoustic panel and acrylic on canvas in 2 parts, 48 × 48 × 3 inches each. Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, Patron Gallery. © Jennie C. Jones.

Jones takes up the musical expression glissando in the title of two paintings here: a word pertaining to the “glide” between musical pitches; or, put another way, to what cannot be strictly defined within a fixed system of notes. Such in-betweenness is also captured by Jones in numerous visual passages in her new works, where strips of red on the edges of both panels in a diptych, for example, create a pink reflection on the wall’s white surface (blurring the neat distinction between artwork and environment, or figure and ground, and suggesting a permeability). This dynamic appears, too, where the rectilinearity of some pieces, like Deep Glissando (all works 2021), is augmented or conjoined by a graded volume or angled strip, or where color fields host imperfections so that an apparently taut formalism never allows for the denial of objecthood. The works constantly elide neat definition.

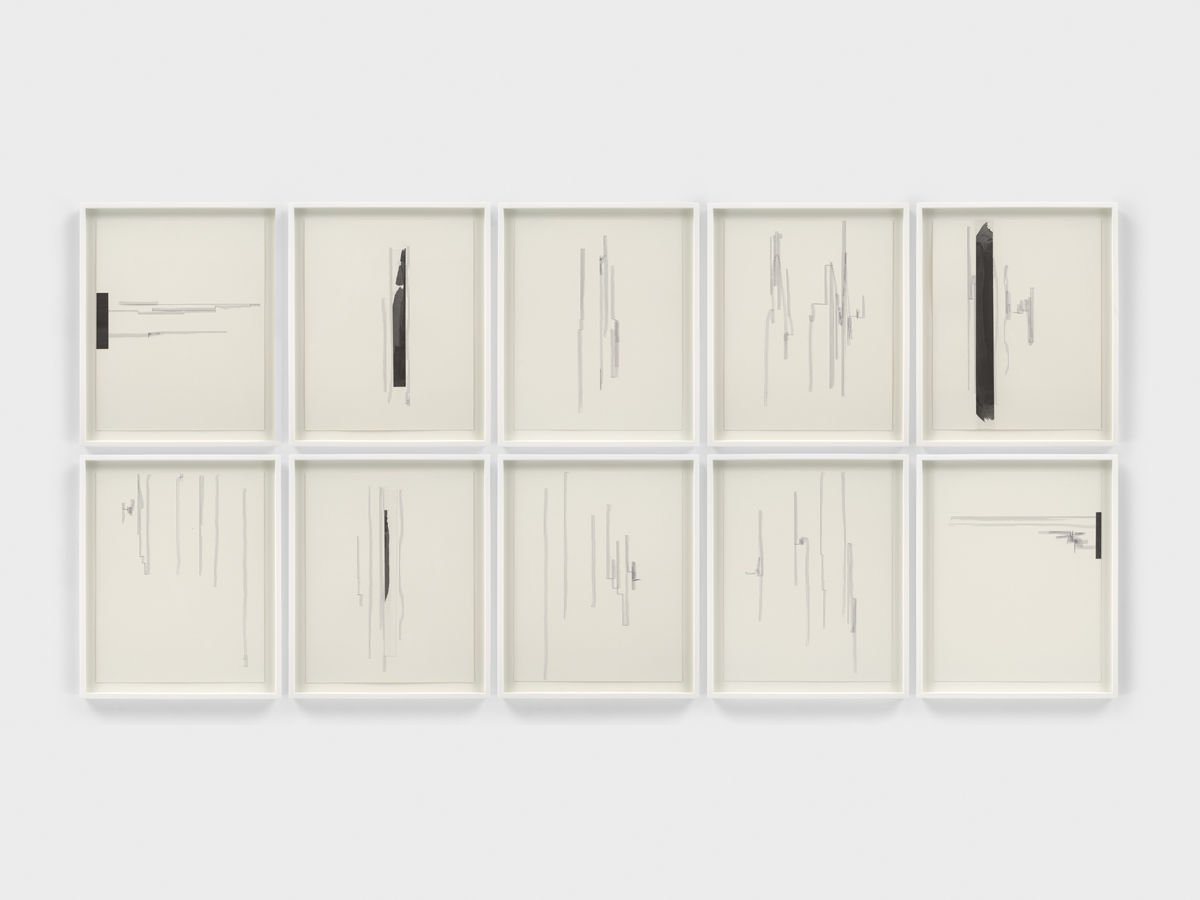

Appropriately, then, while the exhibition primarily includes abstractions made from stretched canvas, acoustic foam, and panels of felt, viewers entering the main gallery will first encounter a large grid of drawings, Graphite Score, whose spare and fine compositions comprise dynamic and distorted warps and weaves of musical staffs. All are notably missing any clef or note that would articulate a specific pitch. Instead of connecting any sound to a fixed grammar, the artist—while summoning the speculative musical notations of modern composers like John Cage or Cornelius Cardew—puts forward the underlying systems by which sound might obtain specific meaning, effectively subverting their functionality and opening up their structures for play. In a sense, the very absence of sound’s notation (a kind of material “silence”) leaves room for the contemplation of those things that would define sound and, further, give shape to its circulation, whether architecturally, socially, or phenomenologically.

Jennie C. Jones, Graphite Score, 2021. Collage, acrylic, and ink on paper in 10 parts, 20 × 16 inches each. Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, Patron Gallery. © Jennie C. Jones.

An intriguing aspect of these drawings is that many individual pieces feature a strip or block of paper laid on the larger ground’s surface, often marked with a heavy band of black. While one would be forgiven for thinking of Marcel Broodthaers’s famous blocking out of Mallarmé’s Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard, the overlapping realms of musical notation and artwork here create the question of whether the block is intentionally obscuring something beneath or is itself presented as something to be “read”—or both.

Jennie C. Jones: New Compositions, installation view. Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, Patron Gallery. © Jennie C. Jones.

Such tension is also found everywhere in the abstract constructions on view. Most works typically take a monochromatic canvas (with some slight variation in paint application) as their ground, which is then overlaid by panels of similarly hued acoustic panel and architectural felt, with optical zips made by strips of felt dividing some canvases or affixed to the frames of others. These panels and strips are at once part of the piece and mask its ground, rendering inaccessible whatever lies beneath. What comes to mind is another anecdote occasionally told by Jones regarding Miles Davis’s disposition to perform with his back turned to the audience: while clearly invoking Minimalism on first sight, her pieces in a sense also have their backs turned (at least partly) to the viewer, prompting some greater cognizance of the exchange and scene, and of the conditions of engagement created and offered by the room in which one stands. One’s attention is redirected, just as the discrete histories Jones addresses might yet be as well.

Written by Tim Griffin is a curator and writer moving to Los Angeles. During the past decade he was executive director and chief curator of the Kitchen, where he organized projects with Chantal Akerman, ANOHNI, Charles Atlas, Ralph Lemon, Aki Sasamoto, and many other artists. His writing has appeared in publications such as Bomb, October, and Artforum, where he was previously editor.