Alex Chitty produced this series of wall-based sculptures and photographs over the course of two years—the two extraordinary years of the initial Covid disruption, to be specific. In this extended period of close looking and unhurried experimentation, she developed the pieces presented here as a single, ongoing body of work: She refers to the first work we encounter in the gallery, Figs break open of themselves (I, II, III) (2020–22), as “an index of ideas” that holds the “individual chapters” of the other pieces. Within this triptych, we are introduced to the full array of artistic strategies that reappear across the rest of the exhibition—the back and forth between surface and depth, striking configurations of textures and finishes, moments of humor and withholding.

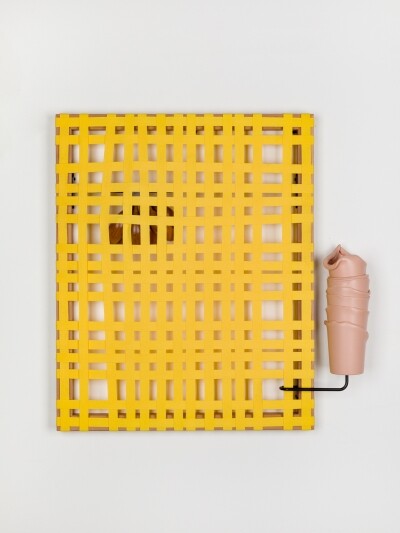

Chitty has long engaged with aesthetic and material elements of the domestic, which she reflects on here as a site of gathering and conversing, of transmitting knowledge, of sharing pleasure and pain, and of cultivating the new. These activities play out slowly over time and across various scenes of everyday life, experiences that she suggests here through repetition and iteration—stacks of bowls and pistachio shells; shelves, windows, grids, and slats; the flat circles of drink trays and the dense orbs of fruits and nuts. The domestic has, of course, traditionally been coded as feminine; the modest scale and detailed construction of these sculptures reference the furniture and architecture of the home—the surfaces and spaces of “women’s work”—while also nodding to the way female contributions to modernist design have largely been erased from its history. Like a Mule through Honey (2022) is held together by the tension in interwoven dowels and strips of fabric, while the spoons seem to be sinking or melting into the bowl below. The artist cites the long and unfinished struggle for gender equality as a theme of this work, with indispensable labor remaining largely invisible. And yet, by refiguring objects of the household, from its wood and metal bones to bits of interior decor, Chitty initiates quietly radical openings for imagining what else might be possible beyond the prescribed structures and routines of our current existence. In three related works—Nudge (2021), Divot (2022), and Nook (2022)—cast brass seeds, however small, create space for themselves as they interrupt and reorder their surroundings.

The artist plans her compositions from the back of the sculptural plane, imagining herself as the work, looking out toward the world. Here in the gallery, the assemblages further insist on a multiplicity of perspectives. We become especially aware of our bodily position in relation to the pieces as we move around them, trying to see. The works tease us, obscuring tucked-away objects like the leaf-patterned shirt peeking out from around the edges of Lush Understory (2022) or presenting us with images that defy immediate apprehension, such as in the black-on-black embroidery of Idle (Blue Tape) (2022). In the case of the diptych, In Other Words (2022), we must complete our experience of the sculpture by moving from one room of the gallery to another. The components of each of the two parts—including leaves from Chitty’s grandmother’s table and antique glassware—are identical but for their placements. “Same but different,” says the artist.

These dynamics points to the questions about representation that lie at the core of Chitty’s practice—who can do it, how it’s done, and why it so often fails its subjects. In dialogue with the histories of still life painting and female figuration, her sculptural works ask us to consider how we understand these constellations of materials and objects in a form on the wall where we might otherwise expect to view an image. What can we recognize in the intimacy of these arrangements? When do we create our own placeholders, our own abstractions? The photograph Skin of a Grape (2022) features an enigmatic scene of images within the image: a reflection of a foot, a torn newspaper photo featuring a pair of what appear to be a woman’s hands. The layering extends to the frame, with its thick ipe wood (often used in decking, here it extends the plane of the tiled floor of the photograph), off-center aperture, and counterbalancing corner with colored-pencil shading. The artist similarly opens up a depth of space and time in Ancillary (2022), where she pairs two nearly identical images of a citrus tree branch, the only difference being that she removed a single leaf between shots (“Same but different”). With these subtle actions, she demands that we approach these photographic works as sculptures, too—individual, complex entities that require a different, more involved way of looking.

This care and attention—to the multitude of elements and processes that make up each work, to the experience of the viewer, to the interplay among all these—begin to move us away from the pitfalls of representation and toward the possibilities of embodiment. Within the exhibition, we see burnished wood and polished brass, rubbed over and over to a shiny finish. We see secondhand items gradually collected and objects fabricated in collaboration with a community of artisans Chitty has built over her sixteen years in Chicago. It seems fitting, then, that the final element of the presentation unfolds in Patron’s living room area, where a number of Chitty’s older works are placed among the sofa, chairs, and tables, and back toward her site-specific and ever-changing plant wall, Midnight Gardening (2021) at the entryway. The artist weaves the chapters of the exhibition together by a trail of threads, some knotty and entwined, others divergent or still indeterminate, looping us into a vital dialogue on perception, understanding, interdependence, and change.

- Anna Searle Jones

Alex Chitty

Visual Art Source

Jan 14, 2023

Jan 14, 2023