An artistic life

Chicago Reader / May 3, 2023 / by Kerry Cardoza / Go to Original

At 90, sculptor Kay Hofmann still works every day. “I think that’s what’s kept me young.”

I always said I was going to be an artist,” Kay Hofmann says. “It’s all I was interested in.”

The 90-year-old artist has a startlingly clear statement of purpose: to make art, primarily hand-carved stone sculptures, no matter what. And she has done exactly that, creating countless works over her long and storied career, just a sliver of which are on view at PATRON in her solo exhibition “Being and Becoming.”

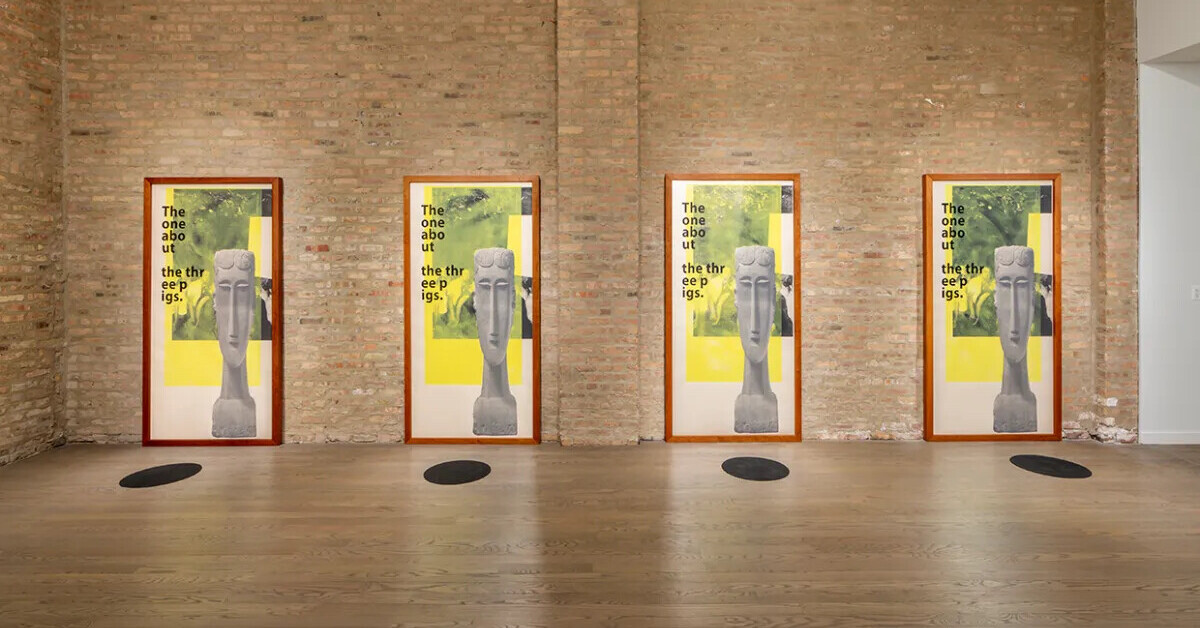

The show includes a bevy of small, paperweight-sized sculptures and a handful of larger works, all made out of various stones and all created over the course of the pandemic. Her pieces are typically of female forms, depicted somewhere between abstraction and representation. They’re flowing, organic compositions—with long, windswept hair or in various states of repose. Sometimes the forms are intertwined with another body; sometimes they’re swimming or appear to be emerging half-formed from the stone. They are flawless in execution, polished to a glossy brilliance.

Hofmann, who was born in Green Bay, Wisconsin, reckons that she first became interested in sculpture at around three years of age. Her father, a stonecutter by trade, was also a duck hunter. He used to carve wooden duck decoys in their basement, and Kay would watch him for hours. Though she wanted to try woodcarving herself, her parents told her she was too young and instead gave her sculpting clay. She sculpted everything in sight: likenesses of the neighborhood dogs, horses. Her father called these early works “her statues.”

After high school, in the early 50s, Hofmann attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, then a much different establishment than the corporatized environment it is today. Classes were held in a basement, she recalls, with no windows. But students and teachers alike were dedicated to their work. “I just thought everybody was a genius,” she says.

She then won a fellowship to spend a year in Paris at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, where she studied under the sculptor Ossip Zadkine. Paris had not yet finished rebuilding after World War II, and Hofmann and her classmates would scour the city for material: chunks of buildings or stones. One day she happened upon workmen cutting down trees along the Champs-Élysées, and they were kind enough to cut her some pieces to take back to her studio. Moving, one of the pieces made out of that tree, was on view in Hofmann’s first exhibition with PATRON in 2019. Standing 19 inches tall, the dark horse-chestnut piece shows a standing, full-bodied figure, one hand on their hip and the other raised to the side of their face. Moving is chunky and angular, the pose both tranquil and spirited.

Hofmann’s relationship with PATRON began in 2017; the backstory of their meeting seems both random and predestined. It all started on Craigslist, where Hofmann had listed some lucite display cubes for sale. It was December 2015, and she was in the process of trying to sell some property in Elmwood Park, where she had lived and worked for many years after being priced out of Chicago. There, she had her studio and a retail shop, named Forever Young, where she and her daughter sold collectible toys.

Mary Eleanor Wallace came to buy the display cubes for her retail project space, Tusk, which had opened in Logan Square in 2013. “She had mentioned to me that she had more of them if I was interested, but her sculptures were on them, and they were very heavy,” Wallace says. “Of course that sparked my curiosity… . Like, she’s standing in her collectibles toy store in Elmwood Park. I can only imagine, what kind of work does this woman make? You know, what could this be, and it’s heavy?”

So Hofmann took Wallace into her studio, which was packed with dozens of sculptures of various sizes, displayed on platforms of different heights. “I was in awe, to say the least,” Wallace says. She was immediately drawn to the work and asked Hofmann that day if she’d be interested in showing some of her pieces at Tusk.

The two have since become dear friends, completing a StoryCorps interview for NPR in 2021. Wallace marvels at Hofmann’s generosity in sharing her work that day. “I think maybe we did have some instant connection or trust. I think that I kind of identified with her pretty immediately,” Wallace says. “Just seeing how active she was made me want to try and celebrate and do whatever I could to share her work.”

Wallace displayed some of Hofmann’s sculptures in a corner of the store and posted images on Tusk’s Instagram, trying to drum up interest in the artist’s work. In the summer of 2016, Wallace installed a pop-up exhibition of Hofmann’s work, surprising her with an impromptu opening.

The display at Tusk is how local artist Mika Horibuchi discovered Hofmann’s work. She lived near Tusk at the time but hadn’t been inside until one day when she was passing by and saw Hofmann’s sculpture through the window. “I went in and I was like, ‘What the heck are these?’” Horibuchi says. She was struck by the work and Wallace helped the two connect for a studio visit. Horibuchi helps direct the Hyde Park artist-run gallery 4th Ward Project Space and was interested in organizing an exhibition of Hofmann’s work.

“Meeting her for the first time was totally astounding,” Horibuchi says. In those days, Hofmann’s dove Sweetie would keep her company in the studio, cooing from its perch. (Hofmann raised doves for many years, and the birds often make their way into her pieces.)

Horibuchi was drawn to Hofmann’s devotion to her work. “I guess it’s something that is immediately recognizable, this type of craft, this type of labor that you just don’t see anymore,” she says. “I think you could immediately see like an unimaginably long, lifelong practice built into one piece.”

Horibuchi says Hofmann’s show, in 2017, was one of her favorite exhibitions at 4WPS. “She’s one of the purest artists I’ve ever met.”

Horibuchi’s enthusiasm for Hofmann intrigued her gallerists at PATRON; the gallery’s owner-directors, Julia Fischbach and Emanuel Aguilar, decided to visit Hofmann’s studio after seeing just one image of her work on an exhibition postcard. By that time, Hofmann had moved to the more affordable Rockford, where she works out of her sunroom and her garage.

“When you sort of step into her universe, it’s kind of magical,” Fischbach says. “After we had conversed for a while and been standing in her studio area, I just said, ‘I don’t want to walk out of here without something.’” She bought a piece on the spot.

Hofmann works every day, whether it’s for an hour or a full day. She says her most productive period was probably after her divorce. (She was married for 23 years.) “All of a sudden being able to do what I wanted to do and having all the time in the world. I probably got more done in the ten years after that—larger pieces, more pieces,” she says.

Hofmann likes doing the work by hand, from carving the stone to polishing, even though it takes a toll on the body. Sometimes when she works, her hands turn purple. Still, besides a brief period when she worked with granite, she has shied away from using power tools. “There’s something that you can’t do with a pneumatic tool that you can do with your hands,” she says. “They just sort of blur over shapes.”

She doesn’t keep track of how long it takes to make a piece. She seldom sketches out an idea before starting to work, though she does a lot of drawing, sometimes drawing directly on the stone. Many of her stones she got raw from Europe or Colorado, where she used to teach occasionally at Blackhawk Mountain School of Art. She would hike out to the nearby stone quarries and pick out stones to ship back to Illinois. She preferred pieces that were dynamited out into raw pieces rather than cut into rectangles. “I could see myself inside the shape.”

That’s how the miniatures in her PATRON show came to be; they were sculpted from cast-off chunks of previous works that she collected for decades. The “minis,” or “chips,” as she calls them, sit on geometric-shaped bases, in the same or contrasting materials. They come from samples from her father’s stonecutting business, that he’d saved for her.

Hofmann often works on several pieces at a time. As she was working on the minis, she’d line up a row of other pieces, so she could look at them and get ideas at the same time. She made about 75 of the small works during the pandemic; there are 19 on view at PATRON.

“When I’m doing these little chips, and I’m working on one, I’m ready to start the other one because I know what I’m going to do,” she says. “Sometimes before I polish the one, I’ll start another before I forget the idea. That’s why I keep saying I’m gonna live to 100; I need that extra time to do the rest of them.”

Looking back on her multidecade career, Hofmann is satisfied with what she’s accomplished, including her late-in-life renaissance and popularity with a younger generation of artists. She says she’s always done what she wanted to do, working supplemental jobs when she had to pay the bills but focusing on her art. “I like doing it. It’s physically hard, but I think that’s what’s kept me young. I enjoy having something come out of the stone.”

The sculptures in “Being and Becoming” were made over the course of the pandemic.; Credit: Courtesy PATRON

I always said I was going to be an artist,” Kay Hofmann says. “It’s all I was interested in.”

The 90-year-old artist has a startlingly clear statement of purpose: to make art, primarily hand-carved stone sculptures, no matter what. And she has done exactly that, creating countless works over her long and storied career, just a sliver of which are on view at PATRON in her solo exhibition “Being and Becoming.”

The show includes a bevy of small, paperweight-sized sculptures and a handful of larger works, all made out of various stones and all created over the course of the pandemic. Her pieces are typically of female forms, depicted somewhere between abstraction and representation. They’re flowing, organic compositions—with long, windswept hair or in various states of repose. Sometimes the forms are intertwined with another body; sometimes they’re swimming or appear to be emerging half-formed from the stone. They are flawless in execution, polished to a glossy brilliance.

Kay Hofmann; Credit: O. Kristina Pedersen

Hofmann, who was born in Green Bay, Wisconsin, reckons that she first became interested in sculpture at around three years of age. Her father, a stonecutter by trade, was also a duck hunter. He used to carve wooden duck decoys in their basement, and Kay would watch him for hours. Though she wanted to try woodcarving herself, her parents told her she was too young and instead gave her sculpting clay. She sculpted everything in sight: likenesses of the neighborhood dogs, horses. Her father called these early works “her statues.”

After high school, in the early 50s, Hofmann attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, then a much different establishment than the corporatized environment it is today. Classes were held in a basement, she recalls, with no windows. But students and teachers alike were dedicated to their work. “I just thought everybody was a genius,” she says.

She then won a fellowship to spend a year in Paris at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, where she studied under the sculptor Ossip Zadkine. Paris had not yet finished rebuilding after World War II, and Hofmann and her classmates would scour the city for material: chunks of buildings or stones. One day she happened upon workmen cutting down trees along the Champs-Élysées, and they were kind enough to cut her some pieces to take back to her studio. Moving, one of the pieces made out of that tree, was on view in Hofmann’s first exhibition with PATRON in 2019. Standing 19 inches tall, the dark horse-chestnut piece shows a standing, full-bodied figure, one hand on their hip and the other raised to the side of their face. Moving is chunky and angular, the pose both tranquil and spirited.

Moving, from 1956, was made from a horse-chestnut tree cut down along the Champs-Élysées.; Credit: PATRON

Hofmann’s relationship with PATRON began in 2017; the backstory of their meeting seems both random and predestined. It all started on Craigslist, where Hofmann had listed some lucite display cubes for sale. It was December 2015, and she was in the process of trying to sell some property in Elmwood Park, where she had lived and worked for many years after being priced out of Chicago. There, she had her studio and a retail shop, named Forever Young, where she and her daughter sold collectible toys.

Mary Eleanor Wallace came to buy the display cubes for her retail project space, Tusk, which had opened in Logan Square in 2013. “She had mentioned to me that she had more of them if I was interested, but her sculptures were on them, and they were very heavy,” Wallace says. “Of course that sparked my curiosity… . Like, she’s standing in her collectibles toy store in Elmwood Park. I can only imagine, what kind of work does this woman make? You know, what could this be, and it’s heavy?”

So Hofmann took Wallace into her studio, which was packed with dozens of sculptures of various sizes, displayed on platforms of different heights. “I was in awe, to say the least,” Wallace says. She was immediately drawn to the work and asked Hofmann that day if she’d be interested in showing some of her pieces at Tusk.

The two have since become dear friends, completing a StoryCorps interview for NPR in 2021. Wallace marvels at Hofmann’s generosity in sharing her work that day. “I think maybe we did have some instant connection or trust. I think that I kind of identified with her pretty immediately,” Wallace says. “Just seeing how active she was made me want to try and celebrate and do whatever I could to share her work.”

Wallace displayed some of Hofmann’s sculptures in a corner of the store and posted images on Tusk’s Instagram, trying to drum up interest in the artist’s work. In the summer of 2016, Wallace installed a pop-up exhibition of Hofmann’s work, surprising her with an impromptu opening.

The display at Tusk is how local artist Mika Horibuchi discovered Hofmann’s work. She lived near Tusk at the time but hadn’t been inside until one day when she was passing by and saw Hofmann’s sculpture through the window. “I went in and I was like, ‘What the heck are these?’” Horibuchi says. She was struck by the work and Wallace helped the two connect for a studio visit. Horibuchi helps direct the Hyde Park artist-run gallery 4th Ward Project Space and was interested in organizing an exhibition of Hofmann’s work.

“Meeting her for the first time was totally astounding,” Horibuchi says. In those days, Hofmann’s dove Sweetie would keep her company in the studio, cooing from its perch. (Hofmann raised doves for many years, and the birds often make their way into her pieces.)

Horibuchi was drawn to Hofmann’s devotion to her work. “I guess it’s something that is immediately recognizable, this type of craft, this type of labor that you just don’t see anymore,” she says. “I think you could immediately see like an unimaginably long, lifelong practice built into one piece.”

Horibuchi says Hofmann’s show, in 2017, was one of her favorite exhibitions at 4WPS. “She’s one of the purest artists I’ve ever met.”

Horibuchi’s enthusiasm for Hofmann intrigued her gallerists at PATRON; the gallery’s owner-directors, Julia Fischbach and Emanuel Aguilar, decided to visit Hofmann’s studio after seeing just one image of her work on an exhibition postcard. By that time, Hofmann had moved to the more affordable Rockford, where she works out of her sunroom and her garage.

“When you sort of step into her universe, it’s kind of magical,” Fischbach says. “After we had conversed for a while and been standing in her studio area, I just said, ‘I don’t want to walk out of here without something.’” She bought a piece on the spot.

The PATRON exhibition features 19 mini sculptures, out of around 75 Hofmann made since the start of the pandemic.; Credit: PATRON

Hofmann works every day, whether it’s for an hour or a full day. She says her most productive period was probably after her divorce. (She was married for 23 years.) “All of a sudden being able to do what I wanted to do and having all the time in the world. I probably got more done in the ten years after that—larger pieces, more pieces,” she says.

Hofmann likes doing the work by hand, from carving the stone to polishing, even though it takes a toll on the body. Sometimes when she works, her hands turn purple. Still, besides a brief period when she worked with granite, she has shied away from using power tools. “There’s something that you can’t do with a pneumatic tool that you can do with your hands,” she says. “They just sort of blur over shapes.”

She doesn’t keep track of how long it takes to make a piece. She seldom sketches out an idea before starting to work, though she does a lot of drawing, sometimes drawing directly on the stone. Many of her stones she got raw from Europe or Colorado, where she used to teach occasionally at Blackhawk Mountain School of Art. She would hike out to the nearby stone quarries and pick out stones to ship back to Illinois. She preferred pieces that were dynamited out into raw pieces rather than cut into rectangles. “I could see myself inside the shape.”

That’s how the miniatures in her PATRON show came to be; they were sculpted from cast-off chunks of previous works that she collected for decades. The “minis,” or “chips,” as she calls them, sit on geometric-shaped bases, in the same or contrasting materials. They come from samples from her father’s stonecutting business, that he’d saved for her.

Hofmann often works on several pieces at a time. As she was working on the minis, she’d line up a row of other pieces, so she could look at them and get ideas at the same time. She made about 75 of the small works during the pandemic; there are 19 on view at PATRON.

“When I’m doing these little chips, and I’m working on one, I’m ready to start the other one because I know what I’m going to do,” she says. “Sometimes before I polish the one, I’ll start another before I forget the idea. That’s why I keep saying I’m gonna live to 100; I need that extra time to do the rest of them.”

Looking back on her multidecade career, Hofmann is satisfied with what she’s accomplished, including her late-in-life renaissance and popularity with a younger generation of artists. She says she’s always done what she wanted to do, working supplemental jobs when she had to pay the bills but focusing on her art. “I like doing it. It’s physically hard, but I think that’s what’s kept me young. I enjoy having something come out of the stone.”