Noé Martínez explores Indigenous ancestry and trauma of colonialism in ‘The Body Remembers’

The Bay State Banner / Mar 20, 2024 / by Celina Colby / Go to Original

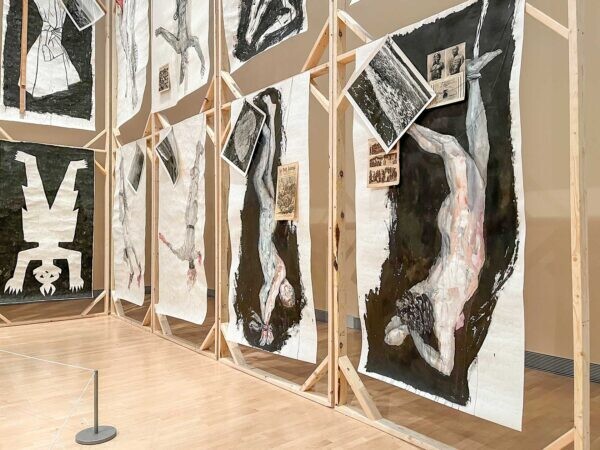

Drawings of mangled bodies, hanging upside down and at times shown in chopped parts, create a towering wall around the “Noé Martínez: The Body Remembers” installation at the Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University in Waltham. The confrontational show addresses the violence and brutality of colonialism on Indigenous people, particularly in Martínez’s own Huastecan heritage.

“I identify as Huasteco, one of the cultures most severely dismembered by the mercantile trade system of the viceroyship and, at the same time, one of the most forgotten by the official story or academic studies of Mexico,” says Martínez. He is the 2024 Ruth Ann and Nathan Perlmutter artist-in-residence at the Rose Art Museum and the latest in a long history of contemporary artists supported by the museum in the earlier stages of their careers.

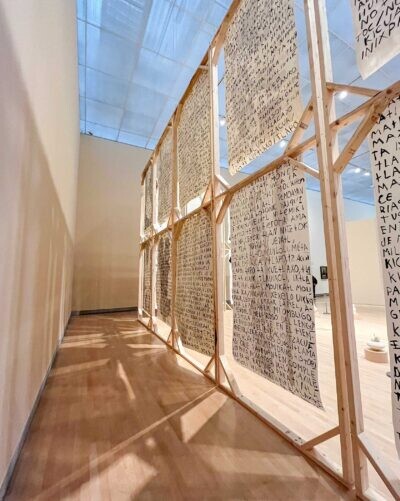

Poems in Spanish and in Martínez’s native, Indigenous language are written on the back of drawings in “The Body Remembers.” PHOTO: CELINA COLBY

Curated by Dr. Gannit Ankori, the museum’s Henry and Lois Foster director and chief curator, with independent curator and scholar Circe Henestrosa, the exhibition brings together three separate bodies of work that create a stirring dialogue about slavery and Indigenous abuse. This is Martínez’s first solo exhibition in New England and it’s the first time any of these bodies of work have been shown in the United States.

The drawings that frame the installation show an array of artistic styles. Some are fleshly and painterly; others are wisps of shading and shadow; a few are stark black-and-white block figures.

“He has to collect and collate different visual markers and visual cues to reconstruct an untold history where there is no documentation,” says Ankori. “This resurrection of his Indigenous culture is a response to the attempt to eradicate it.”

On the back of the drawings, Martínez has written poems in both his native Indigenous language and in Spanish, further resurrecting and preserving a history and culture that is slipping out of collective memory.

Installation view of “Noé Martínez: The Body Remembers” at the Rose Art Museum. PHOTO: CELINA COLBY

In the center of the drawings sits a circle of clay figures styled in the pre-Hispanic art fashion. Martínez has said that these vessels may contain the souls of people who died under colonial rule, the very people depicted in the drawings behind. At the center of the vessels is a cluster of clay figures bundled together.

The third body of work in the installation, working in tandem with the drawings and clay pieces, is a film. In a contemporary apartment, shot upside down in a way that mimics the drawn figures, a line of people move through the rooms, shaking and clutching branding irons used on Indigenous enslaved people. Heavy breathing and cries of desperation create the heart-

wrenching audio.

“I think that learning both about the specificity of Huastecan culture and Indigenous culture in general, before the European colonialism took over the Americas, is important — but also a more general human experience of resilience in the face of trauma and exploitation,” says Ankori.

“The Body Remembers” both revives and educates viewers about the history of the Huastecan people and the atrocities inflicted on them. Martínez probes ancestral trauma here: What from these events lives in his own genes? What gets passed down? The works also connect with the legacy of slavery here in the United States, where similar brutalities were perpetrated on African Americans.

Ankori says, “For us at the Rose, amplifying the untold stories, and the voices that have been silenced, is a really important task.”

“Noé Martínez: The Body Remembers” is on view at the Rose Art Museum through June 16. The museum is free to all.