Artist Noé Martínez questions and heals part of the country’s colonial and slavery history

La Jornada de Oriente / Jul 17, 2024 / by Paula Carrizosa / Go to Original

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f9WQdAK7kOA

The artist as a builder of memory. As an entity that asks how each person has related to the past, noting who has remained silent and who has had the opportunity to speak. The artist who poses a question about history and its relationship with objects that are now historical, that were once everyday, and which need to be questioned and healed from their colonizing past, in an exercise related to one’s own future.

These are the paths that the artist Noé Martínez (Morelia, Michoacán, 1986) carried out in the Museo Amparo ‘s collection of viceregal art as part of the installation The History of the Roads, in which at least 100 objects from the collection - including ivory, polychrome sculptures, paintings, ceramics and textiles - are “cured” in the manner of the indigenous Huasteca worldview to heal their colonizing past, in which slavery was present.

Curated by Tatiana Cuevas, recently appointed director of the Museo Universitario de Arte Universitario de la UNAM , the exhibition was conceived more than five years ago, based on a project commissioned by the Museo Amparo and the questions that Noé Martínez had about the slavery of indigenous peoples during the colonial era, which led him to consult the Archivo de Indias and open the panorama on how indigenous people - not only black people - were taken to countries in Europe, the Caribbean, what is now South America or the African coast, exchanged for horses or cattle, and for other people, and where - around 1631 - a black person was equivalent to three or five Indians, whose “value” amounted to 500 pesos at that time.

“It made sense to me to think about the trade routes that were seen in the collection - from the Amparo Museum - and how each of the objects spoke of a transit, and although not all of them were produced in Europe or outside the Americas, the techniques, the material and the Christian imagery were. For me, each trade route was a route for human trafficking at the time of the Colony,” said the artist.

He continued that by linking these ideas together he began to wonder what was happening with these objects, how he would approach them and how he would question them. Thus, grounded in the worldview of his family of Huastecan origin that “thinks of objects as animated entities,” he knew that these objects in the museum had moved from one place to another, between oceans, carrying a colonial history.

“I was thinking a lot about how to heal those colonial wounds that we have as a society, which I myself carry in my body, so I began to think of the objects as people who needed to be healed, because they are alive,” Martínez said.

He therefore pointed out that, also supported by the questioning of what “we have seen and what has been hidden from us,” and confident that “sometimes by hiding we can see what was not obvious,” he proposed making “a third or fourth reading of what our history is,” and “healing the objects” just as his ancestors had healed him.

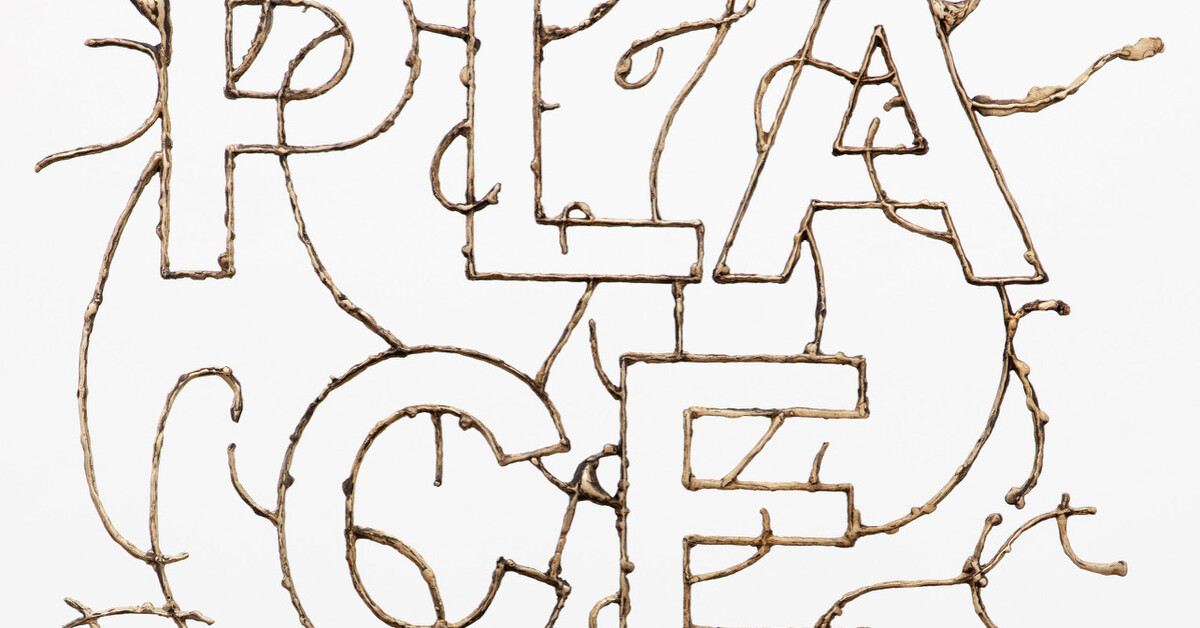

“They cured us with a blanket on top, my grandmother cured us with the steam of endemic plants. I started working on printing plants - muitle, cempasuchil, rue and tobacco - on a series of textiles - blanket and wool -, with which I covered part of the collection so that the materials could be cured: the wood could be cured, the silver could be cured, the textiles could be cured, the ceramics,” she mentioned while touring the installation.

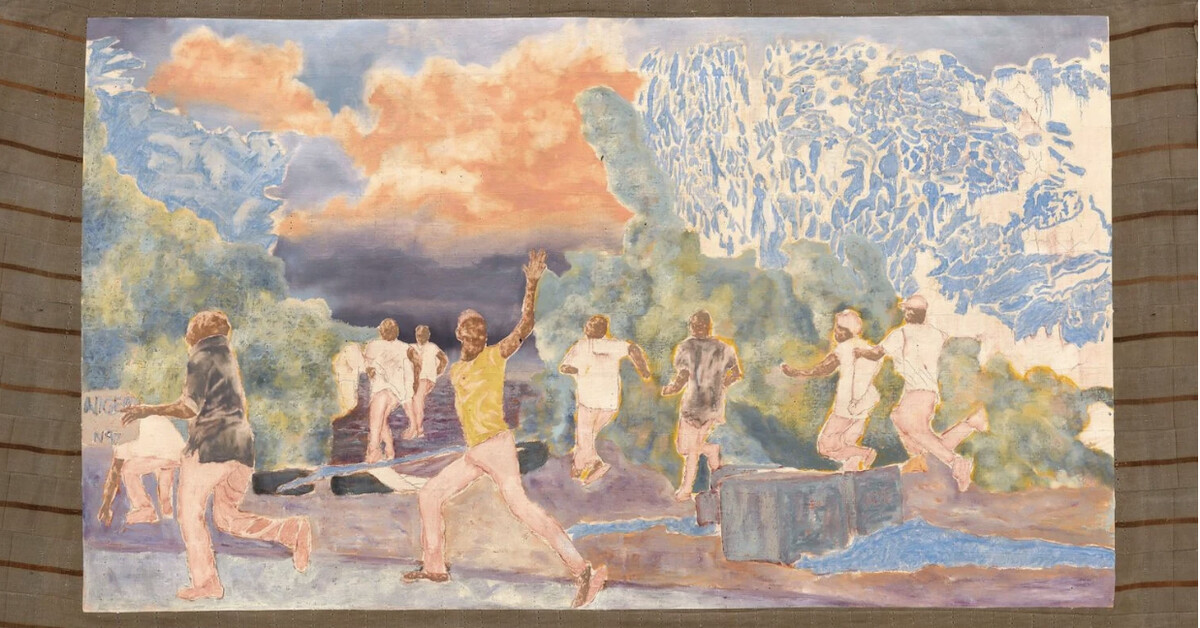

He continued that this healing with the blankets is complemented visually and audibly by the series of videos that he recorded with actors and dancers, who in front of the camera perform jumps, movements, sounds, gestures, silences and many other body exercises that imitate, for example, the neighing of a horse because the population was exchanged for these species, or by an exhaustive walk, just as the indigenous slaves of Pánuco did when they carried 150 kilograms for 25 days, without food or rest, towards the coasts of Veracruz, where their life was worth less than the load itself or any equine.

There is also a map that “synthesizes” these trade and people routes, which allows us to understand how robust this line was in colonial times. “For me it is a personal story, the direct history of my slaves from Pánuco, from the now Huasteca area, the most documented area.”

To close, Noé Martínez highlighted the way in which the Amparo Museum understood the process and allowed the pieces, the same ones that are shown to the visitor, to be veiled as part of the installation. “It was a different way of approaching the objects, which for me are now being cured,” he concluded.