Descendant of slaves: This artist’s work is dedicated to his ancestors

MallorcaZeitung / Jan 20, 2023 / by Brigitte Rohm / Go to Original

Noé Martínez belongs to the Huastec people. In the Kewenig Gallery, the artist brings Mexico’s painful colonial past to light - and strives for healing

Nóe Martínez gently rustles a chain of crystals . Then he creates sounds with a bone scraper instrument that is intended to induce a trance state during ceremonies. The sound seems to resonate after the touch has ended. “For us, the world of the dead is more closely linked to sounds than to images,” explains the artist, who was born in 1986 in Morelia in the Mexican state of Michoacán. What he is showing from January 19th in the Kewenig Gallery in Palma de Mallorca is not an ordinary exhibition, but rather a ritual. A memorial to his ancestors from the Huastec people, whose origins lie in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica.

“I want to close the cycle of life and death with some of my ancestors, whose enslavement began five centuries ago,” says Martínez. The Huastecs were most affected by a little-known, dark chapter of the past: the Spanish conquerors enslaved indigenous peoples, tore them from their homeland and shipped them mainly to the Caribbean, to the sugar cane plantations.

Iron and tobacco

“I’m talking about a moment in history of which no images exist . These are the first,” the artist emphasizes. That is why his imagery was chosen with immense care. Every material, every element has meaning and significance . Martínez created the five works for the exhibition “El hierro y el tabaco” during an artist residency at the CCA Andratx - one of Kewenig’s cooperation partners for the project, along with the Llano Gallery in Mexico City.

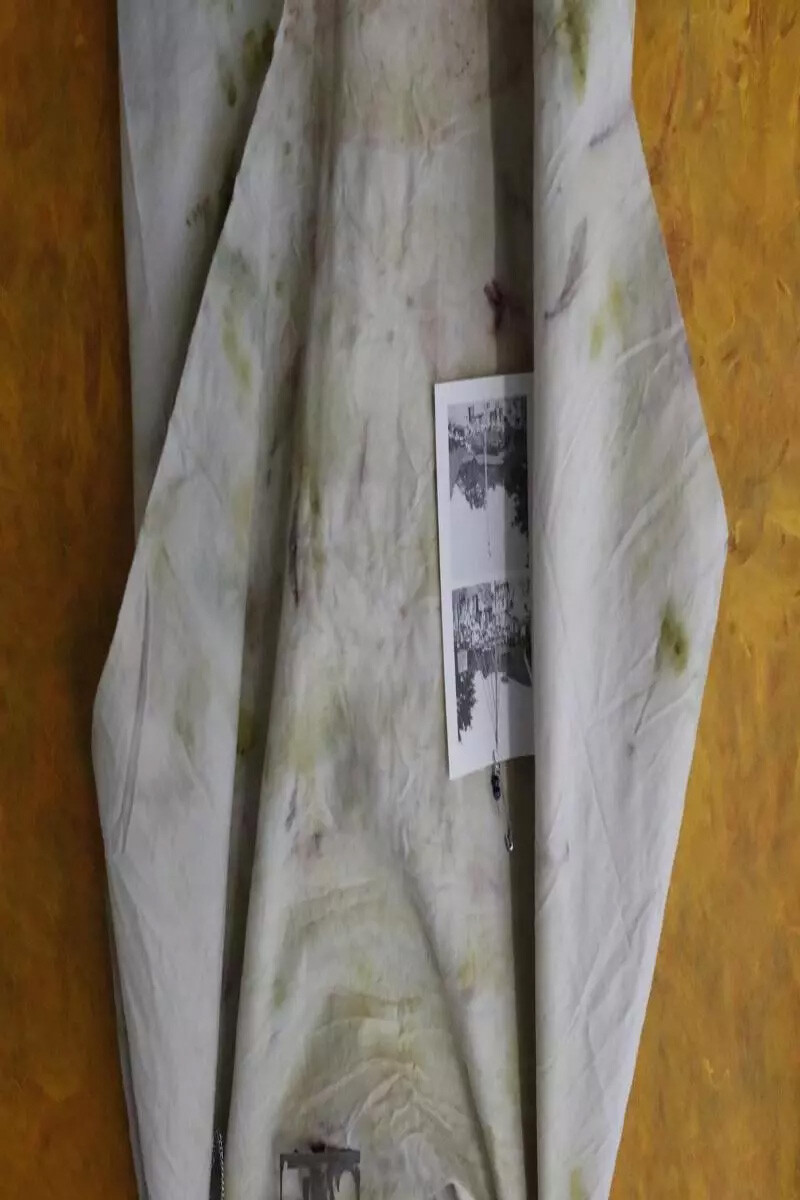

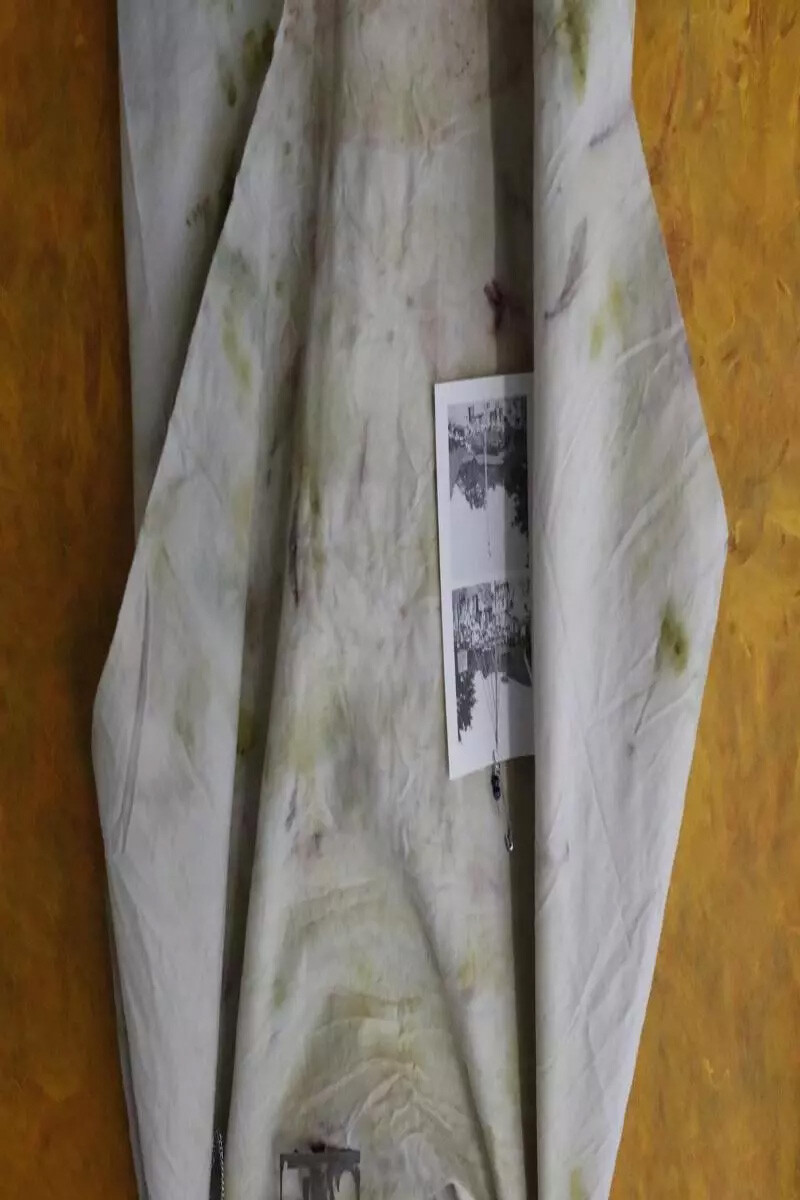

The works move between painting on fabric, installation and conceptual collage and represent the cardinal points to which certain colors are assigned in Mesoamerica. They are based on the types of corn grown there : yellow, white, black and red. The latter corresponds to the area of the Huastecs and therefore appears twice: Martínez has the strongest personal connection with the color, for him it represents the beginning and the end of the circle. The works in red - centerpieces - hang directly next to the former altar of the Oratori de Sant Feliu. For the artist, this is fitting: “This place was made for the Catholic faith. I now take some of this connotation of the sacred , but dedicate it to my ancestors.”

Transformation of Leids

Every detail is charged with meaning, with references to his body - for example, when he stretches out his arms while lying down, this gives the exact measurements of the cotton cloths - and with symbols from his culture. The clothes hanging on the pictures are his own, embroidered with symbols that his people used for tattoos, which he considers a “lost script”. The crystals on the chains allude to the glass from the haciendas and churches of the European conquerors that was scattered to the winds after the fall of the colonial empire. “Huastec shamans dream where exactly these fragments are and they use them to heal and to predict the future,” explains Martínez.

He also wants to transform the suffering he has experienced in his work. For example, a piece of fabric printed with medicinal plants is attached to one work : marigold or rosemary, but above all with the eponymous tobacco , the most powerful and important medicinal plant. He also uses the black semi-precious stone obsidian, which symbolizes the sea - a dark and at the same time shining place that is the seat of the gods in his culture. Martínez uses the obsidians to decorate European symbols that were once used to brand slaves - in order to heal the irons. “Objects and places can also become sick in our imagination,” he says.

Branding iron and poetry

The metal branding irons are another central element of the exhibition. The reproductions snake through the room like a row of slaves chained together. They bear the letter “G” for “guerra”, i.e. prisoners of war, or “R” for “rescate”, i.e. slaves whose souls were supposedly “saved” by Christianity. There are exactly twenty of them , because this number stands for the limbs and thus for the body.

They are inscribed with lines from Martínez’s poem “El sudor de las plantas.” They are fragments, like the story, which has only been passed down in fragments. With the text, Martínez impressively put into words a nightmare that haunted him several years ago: It sent him on his way from the port to a slave market . “In the Archivo General de Indias in Seville, I found documents that described almost every detail of my dream. That was shocking for me,” says the artist, who bases his work on careful research . What were once symbols of slavery, burned into the skin of the Huastecs, are now irons that, infused with words, tell us of the pain suffered.

Nóe Martínez gently rustles a chain of crystals . Then he creates sounds with a bone scraper instrument that is intended to induce a trance state during ceremonies. The sound seems to resonate after the touch has ended. “For us, the world of the dead is more closely linked to sounds than to images,” explains the artist, who was born in 1986 in Morelia in the Mexican state of Michoacán. What he is showing from January 19th in the Kewenig Gallery in Palma de Mallorca is not an ordinary exhibition, but rather a ritual. A memorial to his ancestors from the Huastec people, whose origins lie in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica.

“I want to close the cycle of life and death with some of my ancestors, whose enslavement began five centuries ago,” says Martínez. The Huastecs were most affected by a little-known, dark chapter of the past: the Spanish conquerors enslaved indigenous peoples, tore them from their homeland and shipped them mainly to the Caribbean, to the sugar cane plantations.

Iron and tobacco

“I’m talking about a moment in history of which no images exist . These are the first,” the artist emphasizes. That is why his imagery was chosen with immense care. Every material, every element has meaning and significance . Martínez created the five works for the exhibition “El hierro y el tabaco” during an artist residency at the CCA Andratx - one of Kewenig’s cooperation partners for the project, along with the Llano Gallery in Mexico City.

The works move between painting on fabric, installation and conceptual collage and represent the cardinal points to which certain colors are assigned in Mesoamerica. They are based on the types of corn grown there : yellow, white, black and red. The latter corresponds to the area of the Huastecs and therefore appears twice: Martínez has the strongest personal connection with the color, for him it represents the beginning and the end of the circle. The works in red - centerpieces - hang directly next to the former altar of the Oratori de Sant Feliu. For the artist, this is fitting: “This place was made for the Catholic faith. I now take some of this connotation of the sacred , but dedicate it to my ancestors.”

Transformation of Leids

Every detail is charged with meaning, with references to his body - for example, when he stretches out his arms while lying down, this gives the exact measurements of the cotton cloths - and with symbols from his culture. The clothes hanging on the pictures are his own, embroidered with symbols that his people used for tattoos, which he considers a “lost script”. The crystals on the chains allude to the glass from the haciendas and churches of the European conquerors that was scattered to the winds after the fall of the colonial empire. “Huastec shamans dream where exactly these fragments are and they use them to heal and to predict the future,” explains Martínez.

He also wants to transform the suffering he has experienced in his work. For example, a piece of fabric printed with medicinal plants is attached to one work : marigold or rosemary, but above all with the eponymous tobacco , the most powerful and important medicinal plant. He also uses the black semi-precious stone obsidian, which symbolizes the sea - a dark and at the same time shining place that is the seat of the gods in his culture. Martínez uses the obsidians to decorate European symbols that were once used to brand slaves - in order to heal the irons. “Objects and places can also become sick in our imagination,” he says.

Branding iron and poetry

The metal branding irons are another central element of the exhibition. The reproductions snake through the room like a row of slaves chained together. They bear the letter “G” for “guerra”, i.e. prisoners of war, or “R” for “rescate”, i.e. slaves whose souls were supposedly “saved” by Christianity. There are exactly twenty of them , because this number stands for the limbs and thus for the body.

They are inscribed with lines from Martínez’s poem “El sudor de las plantas.” They are fragments, like the story, which has only been passed down in fragments. With the text, Martínez impressively put into words a nightmare that haunted him several years ago: It sent him on his way from the port to a slave market . “In the Archivo General de Indias in Seville, I found documents that described almost every detail of my dream. That was shocking for me,” says the artist, who bases his work on careful research . What were once symbols of slavery, burned into the skin of the Huastecs, are now irons that, infused with words, tell us of the pain suffered.