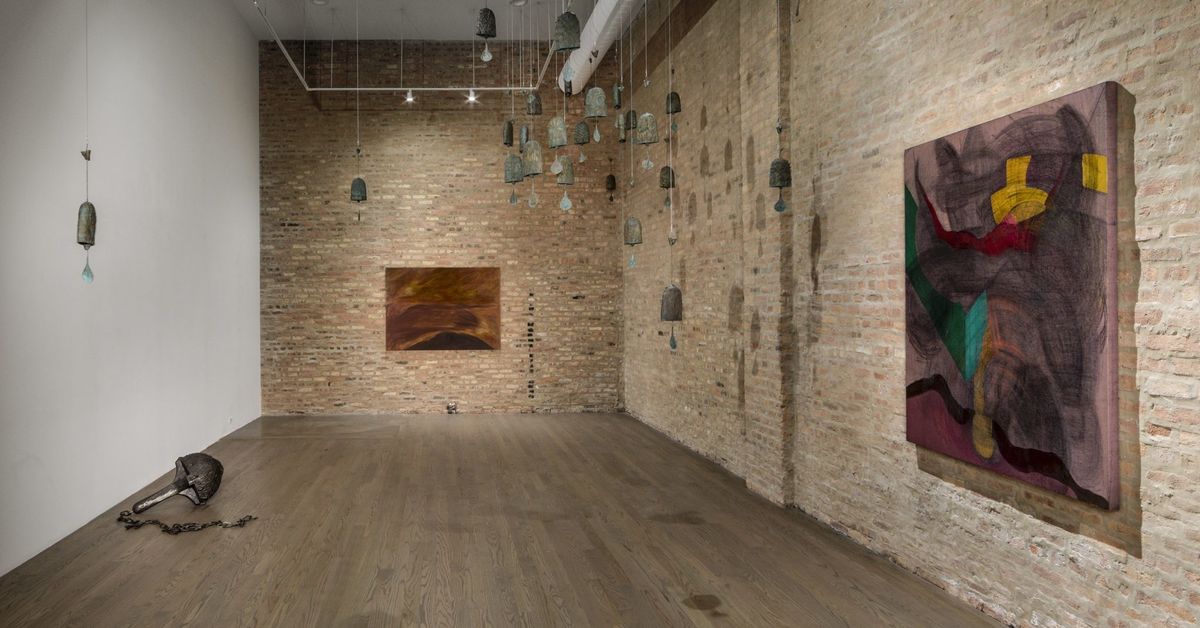

PATRON is proud to present Heft, a three-person exhibition featuring works by Daniel G. Baird, Dominique Knowles, and Kaveri Raina. Occupying all four galleries of PATRON, these paintings, sculptures, and installations stage a ceremonial procession of loss and becoming.

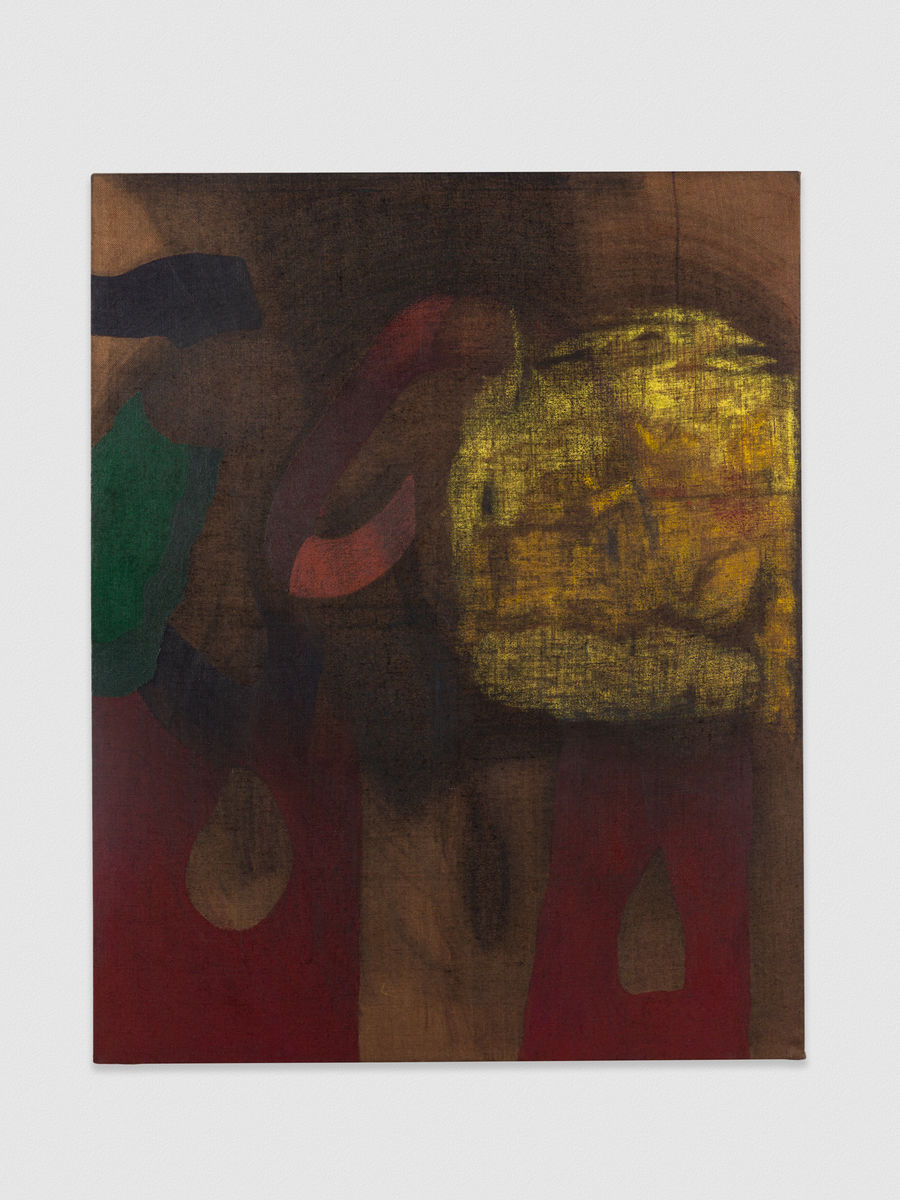

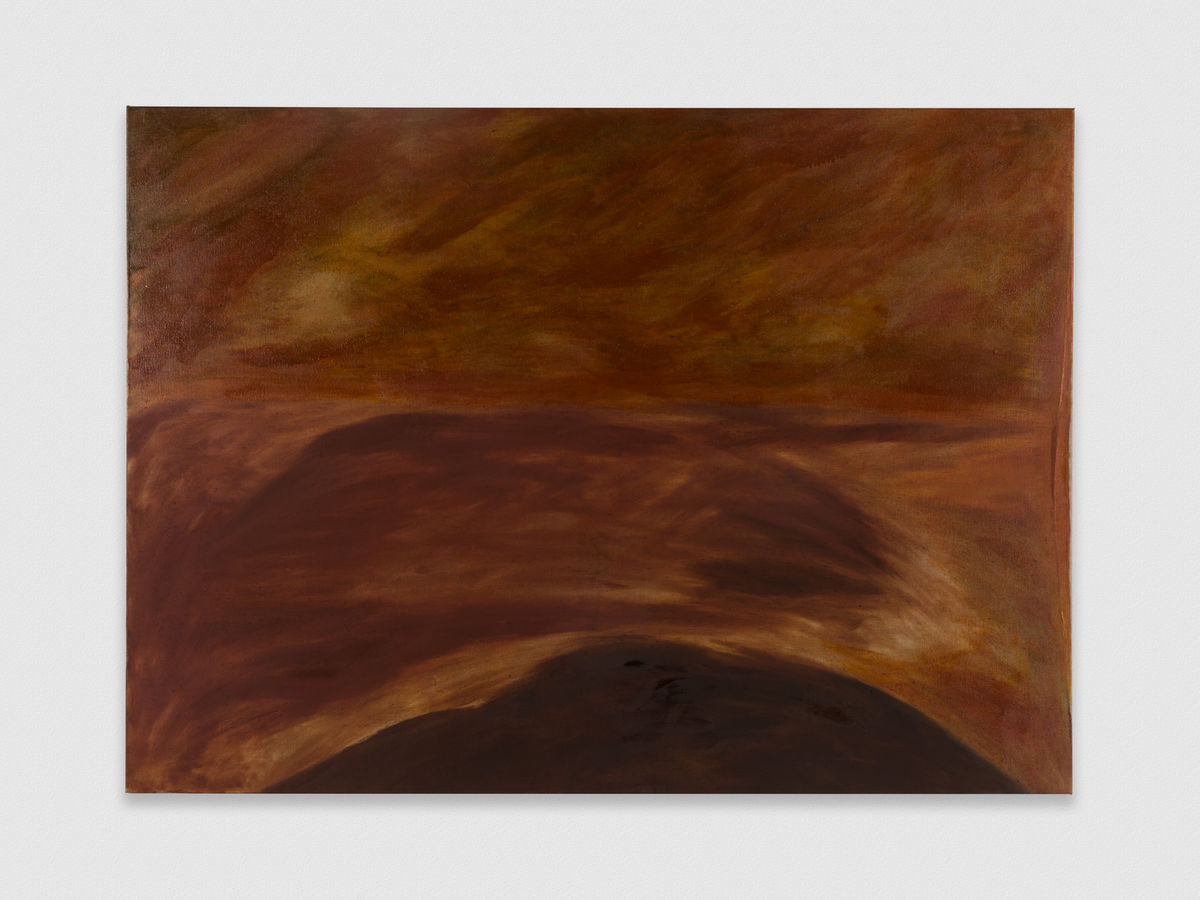

The exhibition includes Dominique Knowles’ suite of dark ochre paintings, The Solemn and Dignified Burial Befitting My Beloved for All Seasons that express the passing of the artist’s beloved horse. The warm, moody amber tones and painterly gestures articulate the movement of the animal against dream-like landscapes that appear to collapse figure and ground. Within the individual compositions and amongst them as a suite, the form of spirit is disembodied and re-embodied, forces flowing in between states of shapes. The larger oil on linen painting in the rear exposed brick gallery comprises a somber, amorphous sweeping gesture which appears to hover over an even darker burial mound.

Also presented is Daniel G. Baird’s installation of sixty-five brass and bronze bells, titled Knell (2021), which refers to the sound of a bell for a death or funeral. In the early Middle Ages, it became tradition in Catholic churches to baptize bells before “birthing a new sound.” Baird here imagines the bell as a type of birthing metaphor, simultaneously incorporating masculine and feminine forms. Each unique object includes a 1:1 cast of the artist’s fingers at the top of the dome shape and within them are phallic-like clappers. The contour of the lip of the bell is in the shape of a threshold of a cave. He began working with the subject of caves in 2017 within a body of work where he created large-scale casts of a cave wall using 3D-printed hardware. Thinking through notions of interiority is a recurring concern for the artist. Resting on a carpet fragment derived from the floorplan of the artist’s childhood bedroom lies a charcoal grey sculpture of Baird’s feet. The positioning of them was inspired by the Greco-Roman statue Sleeping Hermaphroditus.

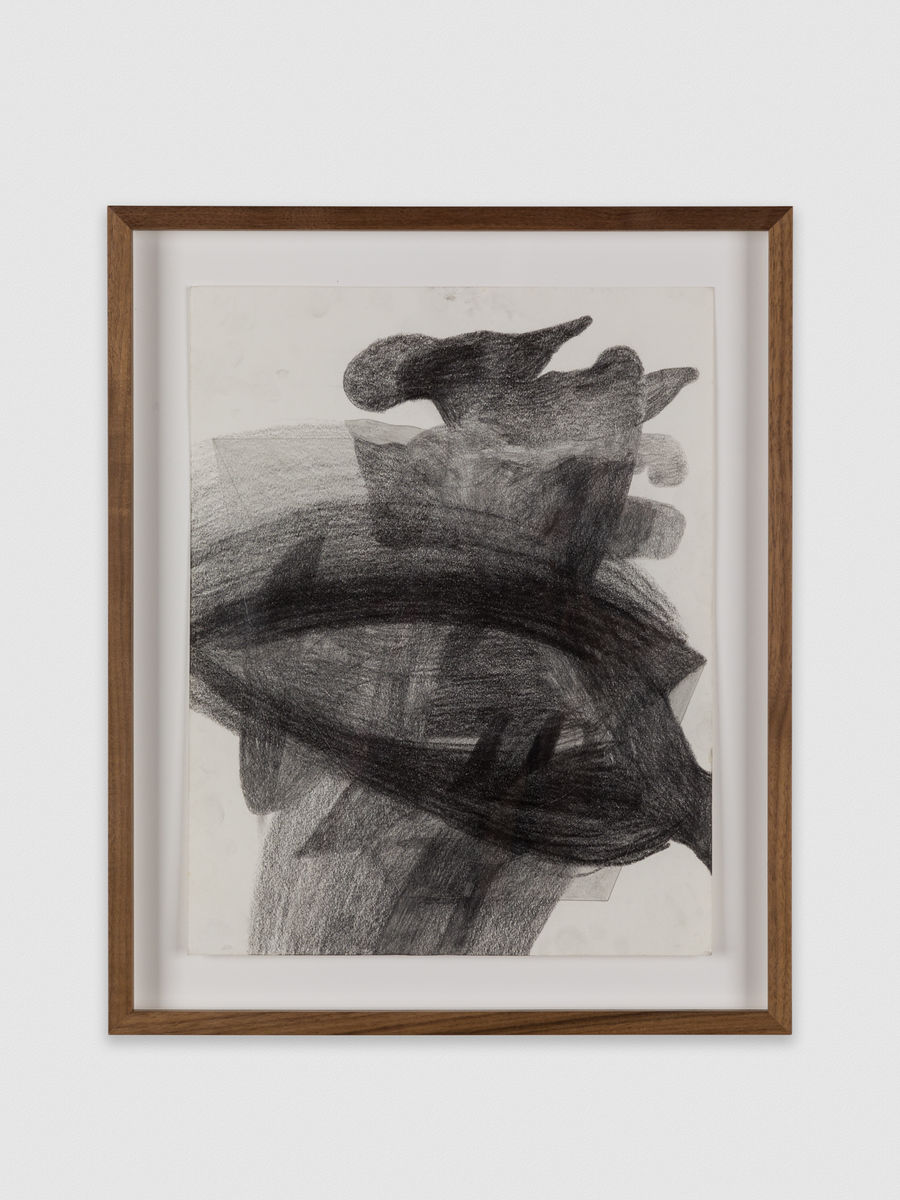

Kaveri Raina’s sumptuous acrylic paintings on burlap, To Perceive is to Suffer; Revisited (2022) and Revolt; Internal Brewing Slow Rage (2021) as well as recent graphite drawings contend with the notion of a figure hovering, or the feeling of a presence or entity that one cannot see. Her interest in this unknowable subject is akin to the shadow described in Amy Sillman’s essay The Shape of Shape, “If you think of shape as figure/ground, then every shape is a figure and the ground is the whole world. Shapes are how you make distinctions, get the lay of the land, or even tell time. And doesn’t everyone have two shapes, really? The first is your own body, which you can’t get out of, and the second is your shadow, which you can’t get rid of.”[1] Raina’s paintings introduce this shadow self where the swirling parts of figures can be understood as an internal dialogue between her own subjectivity and the rest of the world.

Heft, as an exhibition, aims to capture the weightedness of subjectivities: muddied shadow forms that shift slowly, contrapposto on the heated hips of cavities and recesses, absent of being grounded. These works embody parting shapes, comprising both the feminine and masculine, floating toward sheens of brass and graphite, suspended in between a sense of loss and becoming.

[1] Amy Sillman, The Shape of Shape, exh. zine (New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art, 2020), p. 2.

The exhibition includes Dominique Knowles’ suite of dark ochre paintings, The Solemn and Dignified Burial Befitting My Beloved for All Seasons that express the passing of the artist’s beloved horse. The warm, moody amber tones and painterly gestures articulate the movement of the animal against dream-like landscapes that appear to collapse figure and ground. Within the individual compositions and amongst them as a suite, the form of spirit is disembodied and re-embodied, forces flowing in between states of shapes. The larger oil on linen painting in the rear exposed brick gallery comprises a somber, amorphous sweeping gesture which appears to hover over an even darker burial mound.

Also presented is Daniel G. Baird’s installation of sixty-five brass and bronze bells, titled Knell (2021), which refers to the sound of a bell for a death or funeral. In the early Middle Ages, it became tradition in Catholic churches to baptize bells before “birthing a new sound.” Baird here imagines the bell as a type of birthing metaphor, simultaneously incorporating masculine and feminine forms. Each unique object includes a 1:1 cast of the artist’s fingers at the top of the dome shape and within them are phallic-like clappers. The contour of the lip of the bell is in the shape of a threshold of a cave. He began working with the subject of caves in 2017 within a body of work where he created large-scale casts of a cave wall using 3D-printed hardware. Thinking through notions of interiority is a recurring concern for the artist. Resting on a carpet fragment derived from the floorplan of the artist’s childhood bedroom lies a charcoal grey sculpture of Baird’s feet. The positioning of them was inspired by the Greco-Roman statue Sleeping Hermaphroditus.

Kaveri Raina’s sumptuous acrylic paintings on burlap, To Perceive is to Suffer; Revisited (2022) and Revolt; Internal Brewing Slow Rage (2021) as well as recent graphite drawings contend with the notion of a figure hovering, or the feeling of a presence or entity that one cannot see. Her interest in this unknowable subject is akin to the shadow described in Amy Sillman’s essay The Shape of Shape, “If you think of shape as figure/ground, then every shape is a figure and the ground is the whole world. Shapes are how you make distinctions, get the lay of the land, or even tell time. And doesn’t everyone have two shapes, really? The first is your own body, which you can’t get out of, and the second is your shadow, which you can’t get rid of.”[1] Raina’s paintings introduce this shadow self where the swirling parts of figures can be understood as an internal dialogue between her own subjectivity and the rest of the world.

Heft, as an exhibition, aims to capture the weightedness of subjectivities: muddied shadow forms that shift slowly, contrapposto on the heated hips of cavities and recesses, absent of being grounded. These works embody parting shapes, comprising both the feminine and masculine, floating toward sheens of brass and graphite, suspended in between a sense of loss and becoming.

[1] Amy Sillman, The Shape of Shape, exh. zine (New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art, 2020), p. 2.

Between the Strange and Sublime: A Review of Heft at Patron Gallery

Sixty Inches From Center

Aug 22, 2022

Aug 22, 2022