Between the Strange and Sublime: A Review of Heft at Patron Gallery

Sixty Inches From Center / Aug 22, 2022 / by Pia Singh / Go to Original

Featured image: Daniel G. Baird, Aedne, 2022, and installation view of the exhibition Heft. A gallery with white walls and large windows is brightly lit by the sun. In the center of gray oak wood floors, a patch of beige carpet with a protruding edge on the bottom left edge, holds a gray fiberglass cast of two feet crossed over as though the absent figure were lying in repose. There is a foot distance around the carpet and the walls, and a bench by the window. Two tarnished brass bells hang diagonally opposite each other, framing the central installation. Image courtesy the artist and PATRON Gallery, Chicago. Photography by Evan Jenkins.

“You take it in your hand suddenly

and it is kind of empty

Where are these mountains of grief?

Do not think about them anymore

all of that will fit

in the human hand”

– Konstantin Biebl, Warsaw 1986

In Aedne, 2022, two severed fiberglass feet lie in quietude on the carpeted floor of a child-sized bedroom. It is unclear if the absent figure is in repose, or caving under the weight of carrying something too far, for too long. Evoking Bernini’s Sleeping Hermaphroditus, Daniel G. Baird can be imagined lying, cheek to pristinely-trimmed gray-beige carpet, enclosed in a border. A subtle outlet at the bottom left edge marks a doorway, as found on an architectural plan. The threshold, a recurring leitmotif in Baird’s work, becomes a space of negotiation where internalities and externalities extend, a sign that is extremely telling of the works on view at Heft, a three person show at PATRON featuring recent work by Chicago-based Baird, Paris/Chicago-based Dominique Knowles, and Brooklyn-based Kaveri Raina. Proposed by Knowles, Heft is “not so much a group show as much as three solo shows”, explains director Kristin Korolowicz. We examine the cold fleshness of Aedne’s soles, moving to its reverse to find a deep blue oil stained interior cavity that oozes clear resin, contaminating domestic interiority. The deep blue chasm is a metaphor for the emotional, sentimental remnants of what is left behind with the living. The abruptly severed feet, a symbol of the temporal disjuncture that strikes at the time of death.

Aedne is paired with two of sixty four brass and bronze bells, each titled KNELL, 2021, that form a visible continuum between the four galleries that compose Heft. The first pair hang down, from ceiling to eye level, on either side of the carpet. Pointing to the tactility of their making, primordial fingerprints, strokes, and organic oxidized brass colors and textures lend a unique quality to each bell, forcing the question of form and function. I’m reminded of listening to Cosanti bells chime in the summer wind of the high desert, of the ritual of entering a temple in South India where bells of undulating sizes anoint the beginning of an encounter with the divine. Operatively, KNELL seeks to be rung but instead functions as a wayfinder, moving the body from gallery to gallery.

A five part oil on linen panel by Knowles titled The Solemn and Dignified Burial Befitting My Beloved for All Seasons, 2021, initiates the second gallery where a wave of KNELLs stagger diagonally across Knowles’ and Raina’s enclaves. Knowles’ painting reads as a relief, as the scalar variation between panels point to their contingency. Summoning Degas’ Étude de Cheval studies, Knowles captures the tenderness of equine intimacy in sinuous strokes that form a head and nape of a horse’s neck turning left to right, right to left. This discombobulation, away from Muybridge and Meissonier’s equestrian imagery, removes cinematic referent, drawing our focus to the faithful, deep care the artist has for his muse. Central to the exhibition are this suite of Knowles’ earthen hued paintings that form an ode to the passing of his childhood horse, Tazz. The fleeting spirit of love and equine companionship is captured in flesh-like abstraction, where bone and sinew meld into voluminous gestures. The non-sequential nature of the panels mimic the circularity of grieving like memories that come and go in waves.

Image: Daniel G. Baird, KNELL series, 2021, and Kaveri Raina, Untitled (To Hover), 2020. A brightly lit gallery interior with white walls, this is the second room of PATRON’s gallery space. A series of brass bells hanging at various heights occupy the central space of the gallery. Their clappers have drop shapes extending down from the bell that catch shadows and reflections from ambient light. On the far left corner, the shadows of the bells guide the eye to two small, framed graphite works on paper. Image courtesy the artist and PATRON Gallery, Chicago. Photography by Evan Jenkins.

The large-scale installation of KNELL meets Raina in the polysemous forms of shadows cast near two dense graphite on paper drawings, Untitled (To Hover series), 2020. Raina’s drawings are densely stratified, concealing forms that may (or may not) have existed before their burial in thick, sooty silvers. In conversation, the artist shares her experience of meeting Mario Ybarra Jr. at Skowhegan and beginning to work with graphite on paper during a residency at Lighthouse Works in 2018. Characteristically recognized for her large scale abstract paintings on burlap, Raina’s new works break away from the formerly anticipated pleasantness of urgent, emboldened paintings — her markings now expressly introspective, burdened, and misanthropic to a degree so as to not affiliate with purely formal concern. Layering and congealing in central compositions, graphite contaminates the edges of each sheet. We speak about the origins of the forms. Walking to the studio at the beginning of the pandemic, alone and masked in the thick of summer, Raina started taking videos of her shadow: “We were all becoming hyper aware of environments — like what did I just do? What did I touch?” The shadow became an omnipresent entity, moving from life on to the surface of her paintings. The anti-skilled nature of rough graphite strokes are a nod to Lee Lozano’s antithetical compositions — looming, uneasy, and ubiquitous like an anxiety that hovers.

Baird’s KNELL takes form based on the shape of its opening, with lips determined by the contour of a threshold of a cave the artist encountered in Iowa, back in 2014. Inside the cavernous interior, clappers resembling the rounded head of a lingam make the sculptures androgynous, a symbol of creation and quietus all at once. Each bell is held by a cast of Baird’s fingertips, interrupting a linear hanging system and pointing to the artist’s imprints upon its surface. Solitary signifiers arranged in a procession, Baird describes his work as an act of “radical tactility”, where sculptures ponder collapsed time and the act of preserving the transient through the processes of casting. Rethinking the symbolism of the subterranean, Baird returned to the cave equipped with a high powered 3D scanner, three years later. Forced to decipher the location of the scanner to scan the cave in its entirety, he estimated a ‘beginning’ point, accidentally drawing a threshold that forever changed his trajectory. Hollowed yet weighted, the bells are staggered, grotesque, and subliminal anatomical studies that, like Raina and Knowles, blur the division between psyche and body.

Image: (at center) Kaveri Raina, Untitled (To Hover), 2020. Two graphite on paper drawings of ambiguous shapes and figures moving in all directions, yet weighted in the center of the composition, sit side by side in walnut frames. In the foreground, out of focus details of oxidized brass and bronze from Baird’s KNELLs fill the gaps. Image courtesy the artist and PATRON Gallery, Chicago. Photography by Evan Jenkins.

The first of two paintings by Raina, To Perceive is to Suffer; Revisited, 2021-22, characterizes the third gallery. In her ‘drawing-painting’, complex, swelling strokes of graphite partially conquer deep green, bright yellow, and dusty off-pink contours like a rhapsody of forms outside plenary concern. A 2018 graphite drawing sits across the painting, confessing the artist’s unease with the hovering — be it shadow, alter-ego, the weight of history, or the sticky conscience of a silhouetted figure. Four KNELLs hover to the left of the painting, throwing shadows in a magnanimous conversation.

Knowles’ intention to engage with the liminality between life and death, and of shared mourning, demonstrates a certain generosity characteristic of each of the artist’s practices. There are a variety of death rituals that come to mind, such as ceremonies before and after funerary processions in India, or Sky burials amongst Tibetan Monks and Parsi communities where bodies are offered to birds to ascend the soul. I’m also reminded of what it means to live in an internet-driven era of no secrets, caught in a circular system of death and anticipated resurrections. Baudrillard once posited that under the condition of the hyperreal, the event of death is no longer real and can only be present through mimesis. It is thus in the mimesis of the encounter with death, that we can consider those who have passed, either by accident or by choice. This danse macabre between Knowles, Raina, and Baird is of interest as I am taken by the simplest premise of breaking past the individuation of artists in institutional exhibition-making. Facilitated by artist-curator Knowles, in close collaboration with the gallery’s directorial team, the exhibition largely functions as a transitional space, a conjuring that summons experience. Questioning Knowles’ absence from the third room, I move through an arterial corridor only to be met by darkness. The viewer is handed a heavy epilogue written by concealed anatomical masses that refuse to perish.

Image: Installation view of the final gallery room of Heft. An atmospheric, dimly lit gallery with gray oak wood floors has one white wall to the left hand side, and two exposed red brick walls at the far and right wall. Knowles’ piece The Solemn and Dignified Burial Befitting My Beloved for All Seasons, 2022, hangs spotlit at the far wall. A broken, black stain runs down the wall, a foot to the right of the painting. On the right, we see Raina’s Revolt; Internal Brewing Slow Rage, 2021, and in between the two, a series of Baird’s KNELL bells hang down from the ceiling at undulating, steeper heights. To the left is an iron and steel ball held by a claw and chain titled, Anchor, 2022, by Baird. Image courtesy the artist and PATRON Gallery, Chicago. Photography by Evan Jenkins.

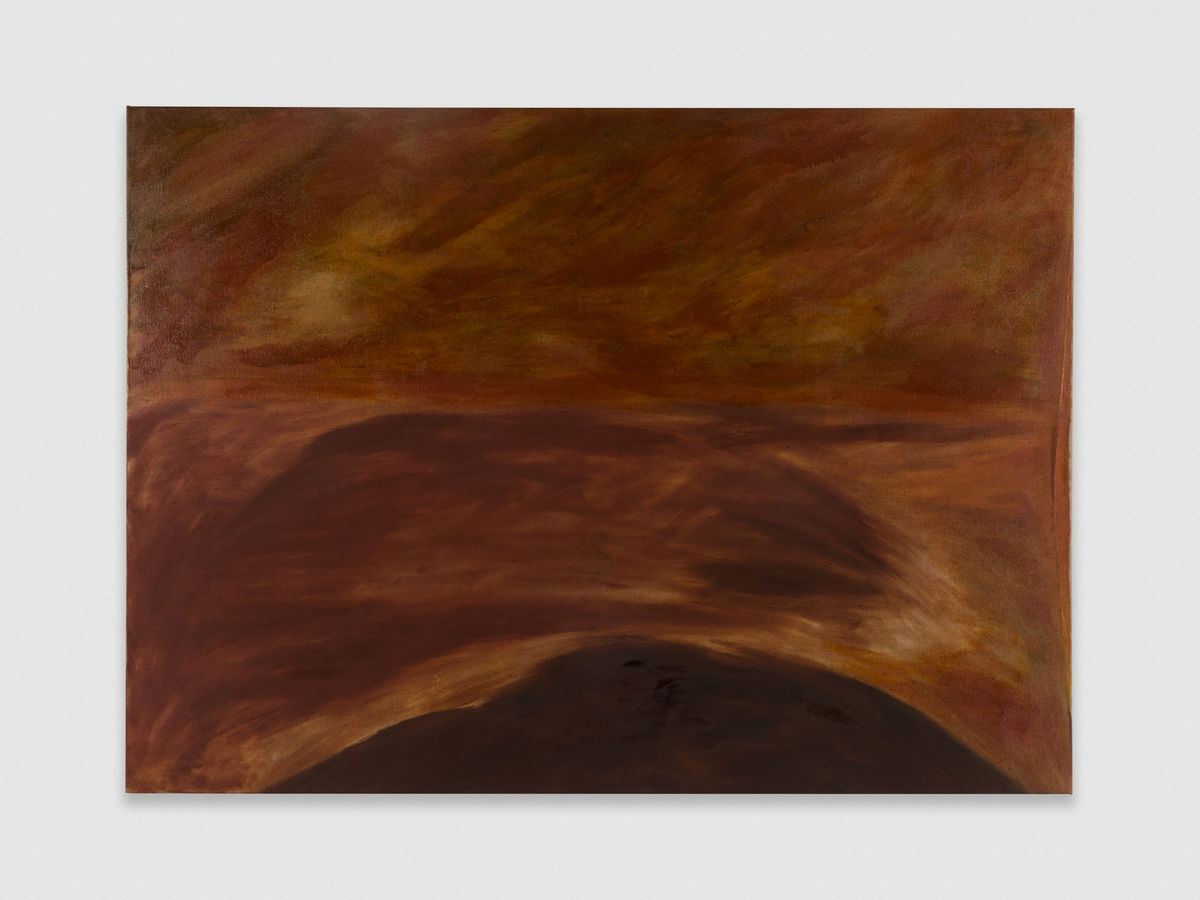

My footsteps grew noticeably weighted under the heft of bereavement. Like an underwater rock climber, I approached The Solemn and Dignified Burial Befitting My Beloved for All Seasons, 2022, starkly lit at the far end of the gallery. The painting depicts a burial mound for Knowles’ beloved in the quietest sanctuary, returning us to the ground underneath where Baird once lay. Dense strokes of deep soil brown demarcate the earth that cradles the animal’s body. Like the cracking of a human skull before Hindu cremation, or the severing of a horse’s head before burial in ancient Icelandic ritual, there is a primal reaction, a repulsion despite knowing the gentility of the subject’s interspecies relationship with the artist. Tawny yellow ochre-brown strokes mixed with dirt create an atmospheric presence above the mound; the spirit of the muse lingering, suspended in animation against Knowles’ internal landscape.

Mounted on an exposed brick wall that wraps around the gallery, the wall bearing Knowles’ grand peinture meets a polished segment of concrete floor to the left. Drawing syncretic meaning from what was once a Vaudevillian stage, the artist’s boundless grief wanders through brick, coming into contact with Raina’s Revolt; Internal Brewing Slow Rage, 2021. Dimly lit, specific undertones of lavender-brown hold Raina’s forceful, metallic strokes that press upon the threshold of burlap, disturbing sharp-edged painted forms. Across the floor, Baird’s Anchor, 2022, mimics and enlarges the shape of the clapper from KNELL, plummeting the artist face down to the depths of the ocean. At the bottom of the anchor are two closed eyes with petal-like finger imprints radiating outward. The artist’s cast fingertips morph into claws, holding on to a weighted mass that is linked to a chain; each link a duplicate of the threshold of the cave.

Image: Dominique Knowles, The Solemn and Dignified Burial Befitting My Beloved for All Seasons, 2022. Oil on linen, 46”³ x 64 1/4”³. An atmospheric abstract painting in earthy yellow ochre-brown tones shows a patch of dark soil at the bottom edge of the canvas, similar to that of a mound. Above the mound, the painter mimics the motion of the curved lines using gestural strokes in reddish earth tones. Atop, strokes in the same tones float up, skywards, implying a separation between monochromatic planes. Image courtesy the artist and PATRON Gallery, Chicago. Photography by Evan Jenkins.

The tragedy of death and the history of grand peinture at the final stage of Heft evokes a space that is both unwanted and intriguing, unspoiled and chaotic, ritual and taboo — and in some sinister way, ambiguous enough to know we are all walking in the same direction, towards death, inevitably. The juxtaposition of weighted subjectivities and contemporary representation of loss is essential as we continue to collectively process mass death and suffering across the world. Immobilized by this gravitas, I surrender to feeling rather than seeing. The Delphic whisperings from another place, the immeasurability of the afterlife (if there is one) and the timelessness of grief is haunting. The multiplicity of human experience lends itself to a more intuitive reading of Heft, proposing a threshold amidst social, economic and political chaos. An improbable altar, a stage for making sense, unbound by existential dread and pictorial rulemaking. Heft is more than an enclosure of valuable objects and ideas. Knowles’ and Raina’s mediation and endeavor to obscure the centrality of human perception, coupled with Baird’s predilection for collapsing the distance between past and present, ground the viewer in subjective interiority, where reason, will and memory are eclipsed by silence and stillness — antidotes to our forever accelerationist tendency.