In collaboration with LLANO (Mexico City) and CCA Andratx, KEWENIG presents the first solo exhibition of Noé Martínez (b. 1986, Morelia, Michoacán, Mexico). His work of speaks from the memory of the colonial past of his native Mexico to reconsider a historical narrative, which from his point of view must be contextualised and understood from new perspectives. Through ethnographic research and his own memory and family history, the multidisciplinary artist creates works that translate into sculpture, writing, photography, sound, video and performance. Martínez offers a critical look at the interpretation of the colonial past of the Huasteca culture and the consequent construction of its present.

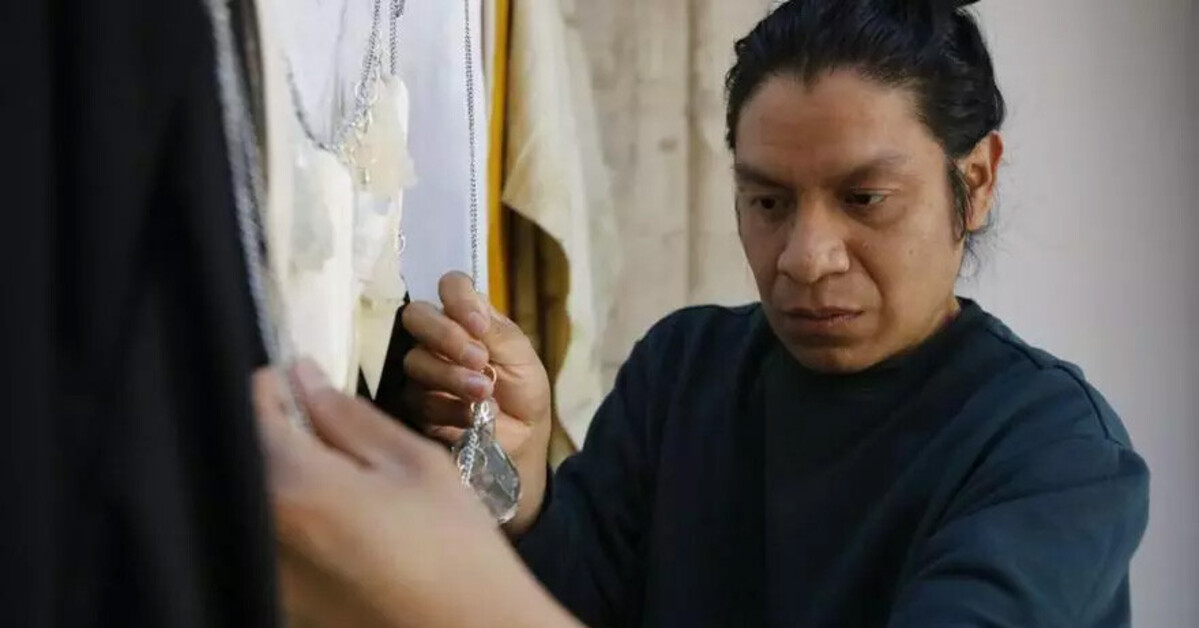

The selected works, created during his residence at the CCA in Andratx, are exhibited in the Sant Feliu oratory under the title “El hierro y el tabaco” (Iron and Tobacco). On five cotton fabrics painted with acrylic primer, embroidered garments are superimposed along with large pendant necklaces – composed of crystals – and pages the book ¨The Dance of the Flyer among the Indians of Mexico and Central America“ by the French anthropologist Guy Stresser-Péan. These compositions meander between painting, installation, and conceptual collage.

The four background colours of the fabric, refer to the colours of corn, depending on the climate of each area. Red in the east, white in the north, black in the west, and yellow in the south. These in turn point to what was the cosmic axis of the pre-Hispanic world. To the Huastec , red corresponds to the red of the eastern sea, the Atlantic. Hence, the red fabric has a double presence, in relation to the artist’s own identity, and as a symbol of the closing of the cycle. Leave the sacred sea and return to it. In Nahuatl, the Yuto-Aztec language, Toki is the Sea and is also the Grandmother, it is considered the place of the Gods. From the yellow cloth hangs a second fabric, the coloured spots on which are the result of infusion and printing with the leaves of ritual plants. The leaves themselves are treated in water with alum and then boiled inside the rolled-up fabric, resulting in a unique impression due to the temperature and ambient factors at the time. The importance of the cloth as a cure is to do with tradition, according to which when placed on the front of the head, one could feel and inhale the smell of infused plants such as rosemary, calendula, tobacco, or rue.

Elongated crystals from old lamps that used to be in bourgeois houses or churches make up the necklaces. These crystals were scattered in nature when the system fell 100 years ago, and since then they have been used by shamans to diagnose illnesses or predict fortunes. They are understood to be charged with power. In the same way, another type of polyhedral crystals and sugar crystals, refer to history. They allude to the the trade of indigenous Mexican slaves to Cuba and Haiti for the cultivation of sugar cane at a time when the growing demand for this crop in Europe established priorities in production. Bone is another material present in the necklaces, referring to ancient musical instruments made from scratched bones. When repeatedly scraped, they create a sound that would bring the listener to the trance-like state necessary for a connection with ancestors. The pieces of clothing hanging from the canvases were worn by the artist himself, which, like a second skin, contain embroidery in the manner of tattoos or body paintings, a sign of Huasteca cultural identity.

An installation composed of 20 pieces of iron that are chained together seems like a crack on the floor of the Oratory. Ten pieces of iron contain the letter G and another ten the letter R, for prisoners of war (in Spanish prisoneros de guerra) or ransom (rescate). These iron letters were used to mark slaves. Each of these has been inscribed with a fragment of a poem by Martínez. Two audiovisual pieces complete the exhibition. One focuses on the transition from the human body to the animal body – the horse. The other one, body percussion, the language codes established by the slaves on board to communicate with each other.

Rescatar la cultura huasteca

El Mundo Primera Edición

Jan 27, 2023

Jan 27, 2023

Descendant of slaves: This artist’s work is dedicated to his ancestors

MallorcaZeitung

Jan 20, 2023

Jan 20, 2023