PATRON is pleased to announce our first solo exhibition with Los Angeles based artist Harold Mendez.

Harold Mendez

At night we walk in circles

September 23 - October 29, 2016

Opening Reception: Friday, September 23, 2016 from 6 -9pm

The Fugitive body

by Yesomi Umolu

Two wrought iron figures stand proudly in the gallery. The first, Margarita (2016) has a flamboyant crown fashioned from feathers, glass, dried foliage and the upturned foam lining of a baseball helmet. The other, I did not become someone different / That I did not want to be (2016) has a dead Staghorn fern encased in a coconut for a head. These figures have travelled a long way from the lush mountains of El Astillero in the Mexican state of Zacatecas and the artist’s front porch in Houston’s third ward respectively. They were but disparate objects before Mendez happened upon them. With his abounding curiosity for the material world and the histories embedded in earthly things, Mendez reclaimed these objects and imagined them anew in his sculptural assemblages. For the artist, this moment of transformation is slow to come; he often collects things and keeps them in his possession for some time, waiting for the right moment to intervene. Once it happens, change can be deceptively simple and occur in an expedited manner, as was the case with these two figures. Of course, to think of the elements of Mendez’s sculptures as being in stasis before the artist makes his mark would be untrue, because they were in fact subject to metamorphosis of form and function due to other natural and man-made forces. So like the Senegalese artist, poet and philosopher Issa Samb remarks with respect to humankind’s relationship to worldly things, Mendez like others simply “takes part [my emphasis] in changing the world, the order of things.”

Beyond this fascinating story of artworks coming into being through the creative process, what do these things tell us about Mendez’s preoccupations with material, form and meaning? For me, Mendez’s figures are counterparts: a crown without a head and a head without a crown. In the gallery they stand diagonally across from each other, as if in conversation. Perhaps we can imagine that they were once united in the form of a single regal figure? If this is the case, then what transpired to dislodge the head from its crown and vice versa? What act of violence has led to this displacement? The answers, like everything in Mendez’s practice are embedded in the specificity of his choice of materials and the narrative clues offered by the other works in the exhibition.

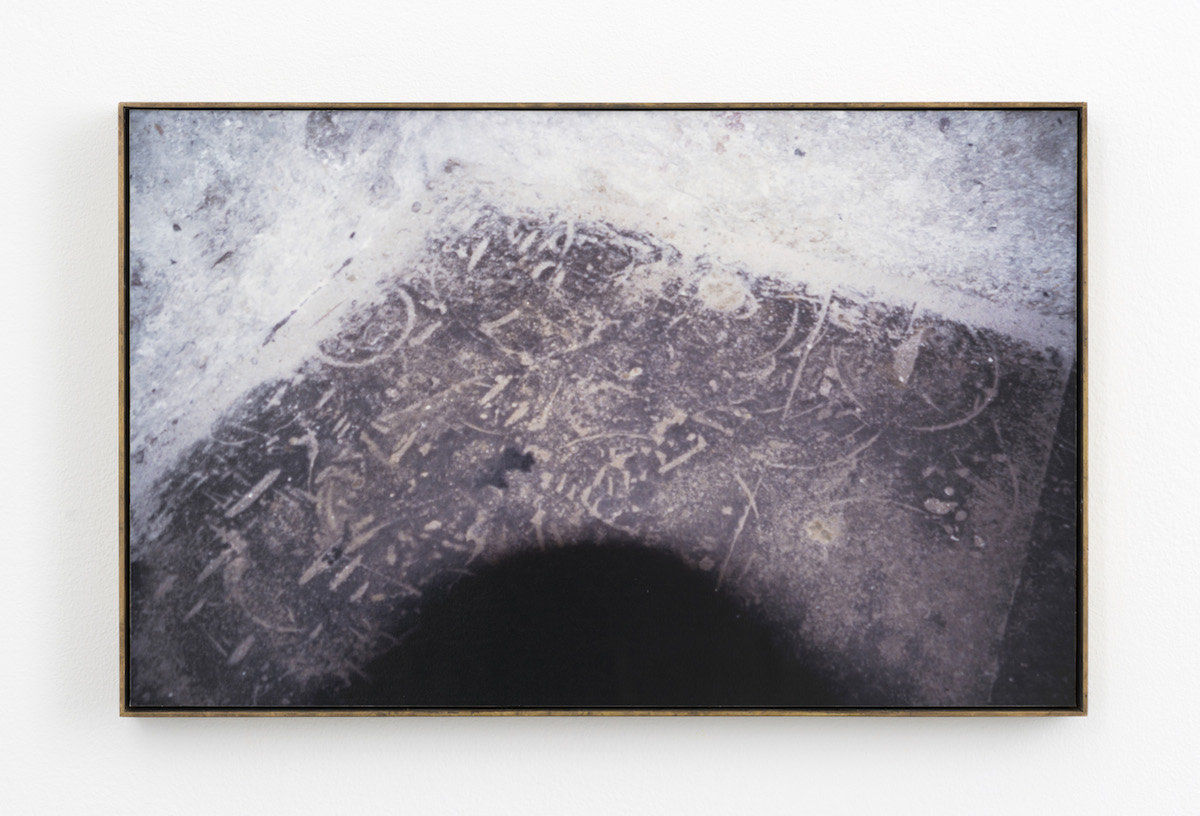

In the far left corner of the front gallery, a print hangs low on the wall as if weighed down by its distressed bronze frame. Mendez took this image (a self-portrait of sorts as it features the shadow of his head), during a visit to Elmina Castle in the Ghanaian city of Elmina in the late 1990s. Chroniclers of history will tell you that Elmina was a key location in the Gold trade in the pre-colonial era. Thereafter, the Portuguese built the castle as a trading post and subsequently with the arrival of the Dutch and the British it was used as one of the main stops in the transatlantic slave trade. Like the other works on view, Elmina Castle (2016) suggests historical narratives of possession and dispossession that are deeply tied to capital, and the exploitation of natural resources and human labor.

Let us gather in a flourishing way (2016) takes us to another location marked by empire. A huge slab of travertine marble acts as a base for a copper vessel imprinted with an image of a pre-Columbian death mask from the Museo del Oro (The Gold Museum) in Bogota, Colombia. Stooping low and focusing the eyes, this ghostly visage comes into view underneath a shallow pool of water. The symbolism at play here is apparent. The combination of travertine marble usually used for monuments and the petals of white carnations that symbolize love and admiration match the honor bestowed upon the deceased who wears the death mask. Consequently, Let us gather…(2016) is to be read as a memorial to a noble and respected figure – possibly the one that lost his or her head?

Throughout the show, this figure’s body comes in an out of view. It is a fugitive body as it appears in fragments of face, head and shadow, and is never fully whole. Peering into the copper vessel, you might catch your reflection fleetingly approximated to the death mask. Are you the missing figure? Is this work therefore a memorial to the self? The anxiety inherent here speaks to the artist’s own ruminations on selfhood and his role in the world. Mendez’s work meditates on notions of belonging that often occupy the minds of those from transnational backgrounds. The different geographical locations represented in the show directly reference his personal trajectory as an American artist of Mexican and Colombian descent, and explore the range of cultural histories and realities that inform his work.

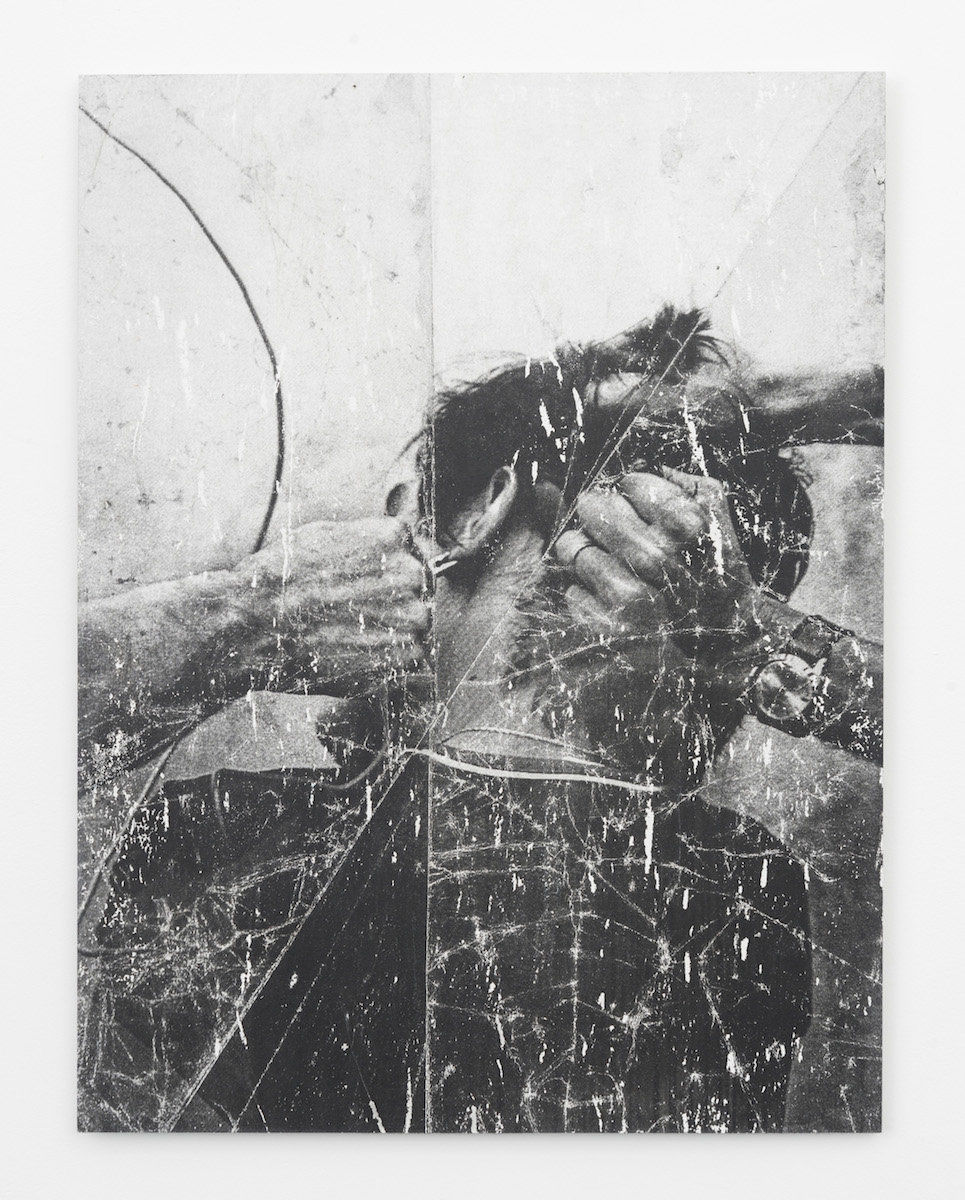

A reflection might also emerge in the mirror featured in If they are not fears, they’re contritions. If they are not doubts, inabilities (After Melitón Rodríguez) (2015). This work represents a more intensive production process on the artist’s part as he deconstructs Xerox prints of images drawn from his archive. Here Mendez engages the sculptural qualities of paper by removing layers of paper pulp through a variety of means including taking to it with a high-pressure water hose. If they are not fears… depicts the studio of Melitón Rodríguez’s, a Colombian photographer known for his work chronicling the modernization of the cities of Medellín and Antioquia in the late nineteenth century. Rodríguez, like many other ghostly figures that materialize in the show is someone that Mendez draws inspiration from. Given this reference, it is important to consider Mendez’s work as exploring modes of image making across sculpture and photography with each artwork existing as a document of a given space (both physical and psychic) and time.

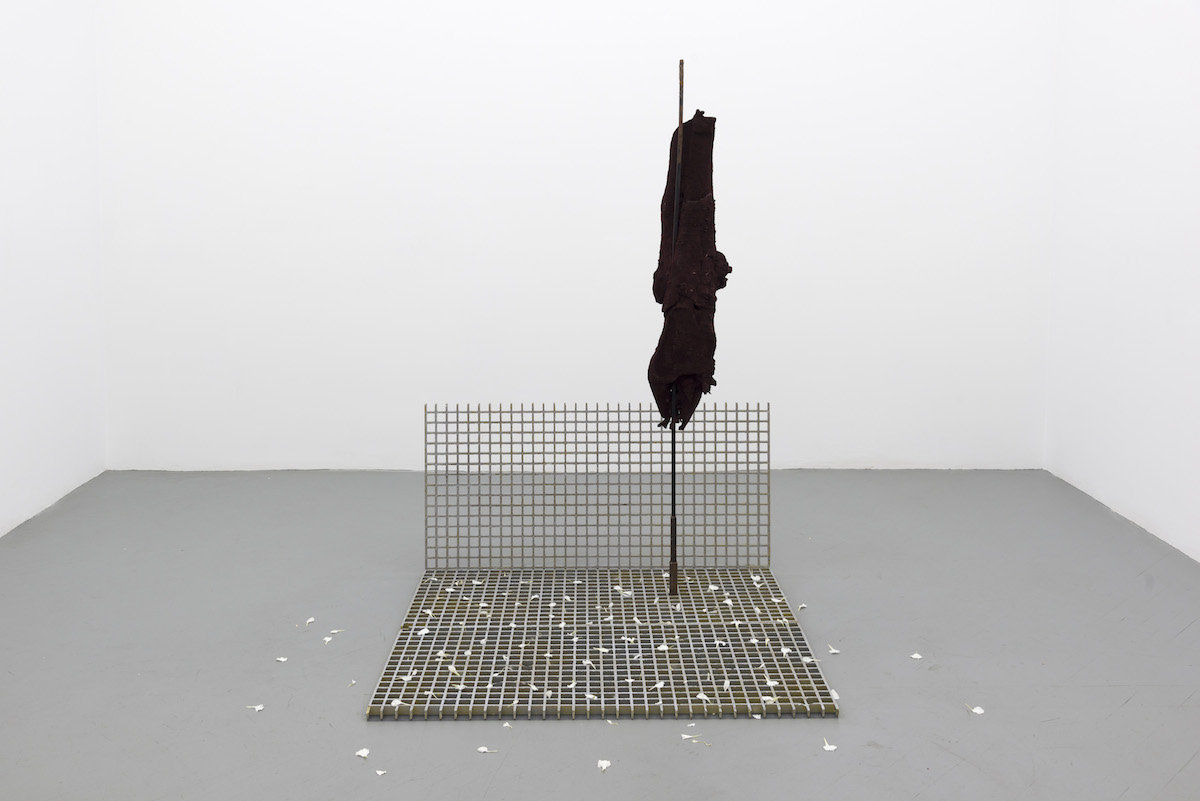

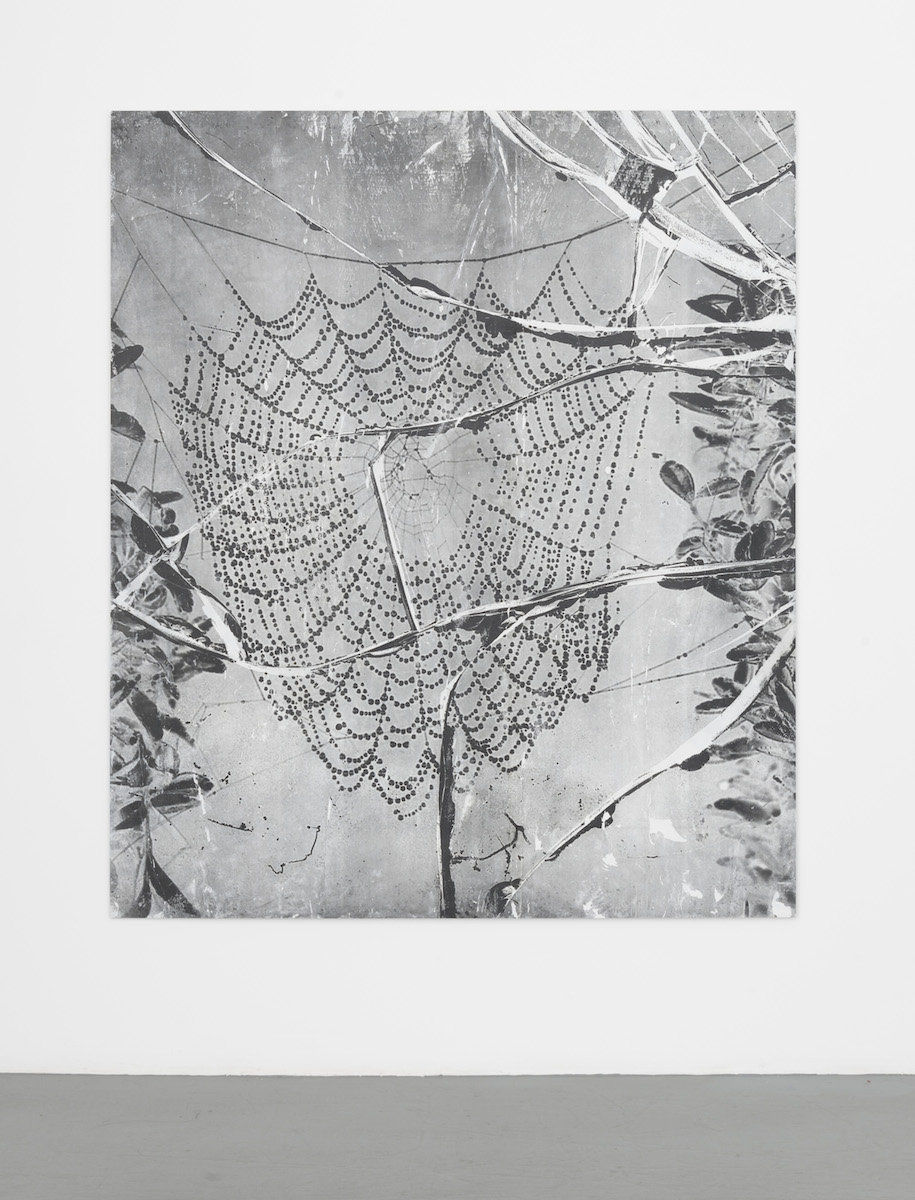

American Pictures transports us to urban memorials. In this work a salvaged tree trunk growing around a piece of wrought iron fence stands on industrial work mats. A velvety layer of crushed cochineal insects transform the surface of the bark into a deep blood red. The sculpture has the air of a carcass left out to dry, the sprinkling of carnation petals at its base consecrating its final resting place. For the artist, it subtly infers the specter of violence in America’s urban centers, which has become ever so pronounced in recent time. In the maddening haze of this moment, where specific bodies are indiscriminately denied their right to breath, where does one find home and solace? A solitary spider builds his web in At night we walk in circles (2016) and we are reminded that what Mexican conceptual artist Abraham Cruzvillegas terms autoconstrucción or “self-construction” or rather “self-determination” is the only respite.

Like the carnation petals that will wilt over time and be replenished regularly, the artworks on view in At night we walk in circles are engaged in a cyclical process of decay and renewal. As well as evoking the practice of Cruzvillegas, Mendez’s work is much indebted to practitioners such as David Hammons, Doris Salcedo, Jean-Luc Moulène and Mona Hatoum who recognize the potential in inscribing meaning to abject objects. Like his predecessors, Mendez merges the poetic and the political to give form to narratives of power, loss, remembrance, and redemption. At the center of this is a fugitive body – that of the artist – who must continuously move between different modes of working and imaging the world in order to give form to our ever shifting realities.

- Yesomi Umolu, Exhibitions Curator, Reva and David Logan Center for the Arts

Harold Mendez

At night we walk in circles

September 23 - October 29, 2016

Opening Reception: Friday, September 23, 2016 from 6 -9pm

The Fugitive body

by Yesomi Umolu

Two wrought iron figures stand proudly in the gallery. The first, Margarita (2016) has a flamboyant crown fashioned from feathers, glass, dried foliage and the upturned foam lining of a baseball helmet. The other, I did not become someone different / That I did not want to be (2016) has a dead Staghorn fern encased in a coconut for a head. These figures have travelled a long way from the lush mountains of El Astillero in the Mexican state of Zacatecas and the artist’s front porch in Houston’s third ward respectively. They were but disparate objects before Mendez happened upon them. With his abounding curiosity for the material world and the histories embedded in earthly things, Mendez reclaimed these objects and imagined them anew in his sculptural assemblages. For the artist, this moment of transformation is slow to come; he often collects things and keeps them in his possession for some time, waiting for the right moment to intervene. Once it happens, change can be deceptively simple and occur in an expedited manner, as was the case with these two figures. Of course, to think of the elements of Mendez’s sculptures as being in stasis before the artist makes his mark would be untrue, because they were in fact subject to metamorphosis of form and function due to other natural and man-made forces. So like the Senegalese artist, poet and philosopher Issa Samb remarks with respect to humankind’s relationship to worldly things, Mendez like others simply “takes part [my emphasis] in changing the world, the order of things.”

Beyond this fascinating story of artworks coming into being through the creative process, what do these things tell us about Mendez’s preoccupations with material, form and meaning? For me, Mendez’s figures are counterparts: a crown without a head and a head without a crown. In the gallery they stand diagonally across from each other, as if in conversation. Perhaps we can imagine that they were once united in the form of a single regal figure? If this is the case, then what transpired to dislodge the head from its crown and vice versa? What act of violence has led to this displacement? The answers, like everything in Mendez’s practice are embedded in the specificity of his choice of materials and the narrative clues offered by the other works in the exhibition.

In the far left corner of the front gallery, a print hangs low on the wall as if weighed down by its distressed bronze frame. Mendez took this image (a self-portrait of sorts as it features the shadow of his head), during a visit to Elmina Castle in the Ghanaian city of Elmina in the late 1990s. Chroniclers of history will tell you that Elmina was a key location in the Gold trade in the pre-colonial era. Thereafter, the Portuguese built the castle as a trading post and subsequently with the arrival of the Dutch and the British it was used as one of the main stops in the transatlantic slave trade. Like the other works on view, Elmina Castle (2016) suggests historical narratives of possession and dispossession that are deeply tied to capital, and the exploitation of natural resources and human labor.

Let us gather in a flourishing way (2016) takes us to another location marked by empire. A huge slab of travertine marble acts as a base for a copper vessel imprinted with an image of a pre-Columbian death mask from the Museo del Oro (The Gold Museum) in Bogota, Colombia. Stooping low and focusing the eyes, this ghostly visage comes into view underneath a shallow pool of water. The symbolism at play here is apparent. The combination of travertine marble usually used for monuments and the petals of white carnations that symbolize love and admiration match the honor bestowed upon the deceased who wears the death mask. Consequently, Let us gather…(2016) is to be read as a memorial to a noble and respected figure – possibly the one that lost his or her head?

Throughout the show, this figure’s body comes in an out of view. It is a fugitive body as it appears in fragments of face, head and shadow, and is never fully whole. Peering into the copper vessel, you might catch your reflection fleetingly approximated to the death mask. Are you the missing figure? Is this work therefore a memorial to the self? The anxiety inherent here speaks to the artist’s own ruminations on selfhood and his role in the world. Mendez’s work meditates on notions of belonging that often occupy the minds of those from transnational backgrounds. The different geographical locations represented in the show directly reference his personal trajectory as an American artist of Mexican and Colombian descent, and explore the range of cultural histories and realities that inform his work.

A reflection might also emerge in the mirror featured in If they are not fears, they’re contritions. If they are not doubts, inabilities (After Melitón Rodríguez) (2015). This work represents a more intensive production process on the artist’s part as he deconstructs Xerox prints of images drawn from his archive. Here Mendez engages the sculptural qualities of paper by removing layers of paper pulp through a variety of means including taking to it with a high-pressure water hose. If they are not fears… depicts the studio of Melitón Rodríguez’s, a Colombian photographer known for his work chronicling the modernization of the cities of Medellín and Antioquia in the late nineteenth century. Rodríguez, like many other ghostly figures that materialize in the show is someone that Mendez draws inspiration from. Given this reference, it is important to consider Mendez’s work as exploring modes of image making across sculpture and photography with each artwork existing as a document of a given space (both physical and psychic) and time.

American Pictures transports us to urban memorials. In this work a salvaged tree trunk growing around a piece of wrought iron fence stands on industrial work mats. A velvety layer of crushed cochineal insects transform the surface of the bark into a deep blood red. The sculpture has the air of a carcass left out to dry, the sprinkling of carnation petals at its base consecrating its final resting place. For the artist, it subtly infers the specter of violence in America’s urban centers, which has become ever so pronounced in recent time. In the maddening haze of this moment, where specific bodies are indiscriminately denied their right to breath, where does one find home and solace? A solitary spider builds his web in At night we walk in circles (2016) and we are reminded that what Mexican conceptual artist Abraham Cruzvillegas terms autoconstrucción or “self-construction” or rather “self-determination” is the only respite.

Like the carnation petals that will wilt over time and be replenished regularly, the artworks on view in At night we walk in circles are engaged in a cyclical process of decay and renewal. As well as evoking the practice of Cruzvillegas, Mendez’s work is much indebted to practitioners such as David Hammons, Doris Salcedo, Jean-Luc Moulène and Mona Hatoum who recognize the potential in inscribing meaning to abject objects. Like his predecessors, Mendez merges the poetic and the political to give form to narratives of power, loss, remembrance, and redemption. At the center of this is a fugitive body – that of the artist – who must continuously move between different modes of working and imaging the world in order to give form to our ever shifting realities.

- Yesomi Umolu, Exhibitions Curator, Reva and David Logan Center for the Arts

Newcity's Top 5 of Everything: Visual Arts

Newcity

Dec 15, 2016

Dec 15, 2016

Harold Mendez

Artforum

Jan 12, 2017

Jan 12, 2017

Editor's Pick: Harold Mendez

Visual Arts Source

Oct 27, 2016

Oct 27, 2016

Show Up: Harold Mendez

Arts + Culture

Oct 21, 2016

Oct 21, 2016