Material World

News Review / Jan 29, 2015 / by Brad Bynum / Go to Original

Nick van Woert is one of the names often mentioned during conversations about Nevada-bred artists who have gone on to proverbial bigger and better things after leaving the state. He graduated from Reno High School in 1997, earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of Oregon, studying architecture, then moved back to Reno for a few years before moving to New York in 2005 to attend Parsons the New School for Design. He’s been based in New York ever since, working full time as an artist and attracting international acclaim. In 2014, he had high-profile solo exhibitions in Italy and the Netherlands. And from January 29 to April 9, his solo exhibition Pink Elephants on Parade will be on display at the University of Nevada, Reno’s Sheppard Contemporary gallery.

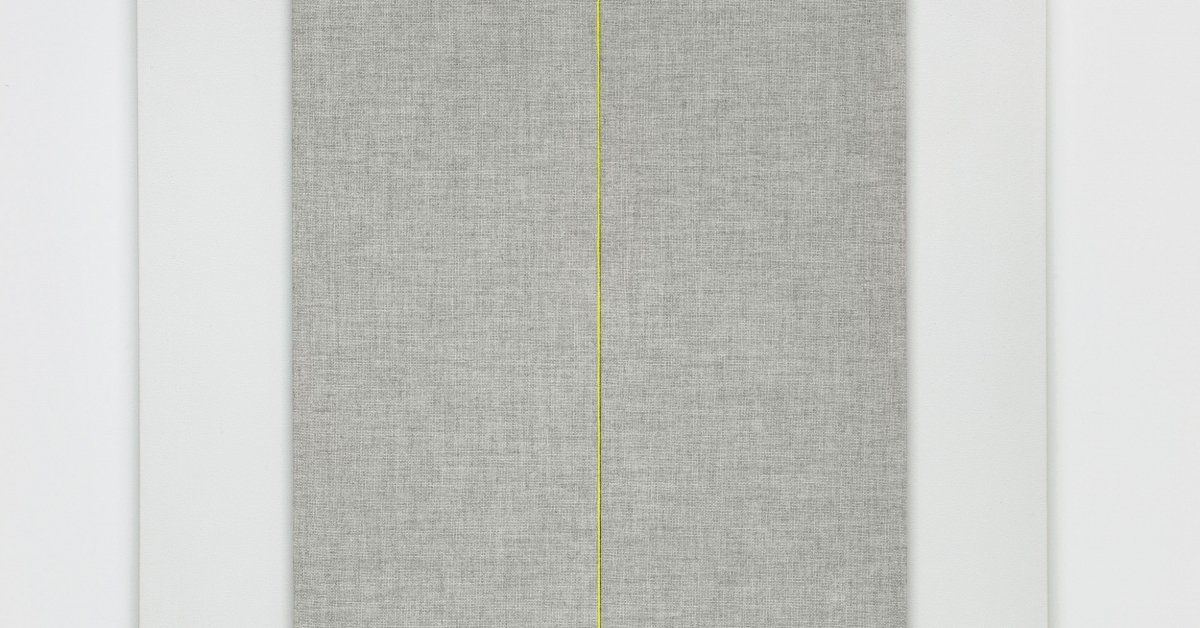

The exhibition includes several large untitled sculptures. Most of van Woert’s work is an investigation of materials. He’s a sculptor, but he views his work as connected to the traditions of landscape painting—art that aspires to recreate the beauties of the natural world.

“There’s only two types of beauty, in a sense,” he said. “There’s natural beauty, which is this uncontrollable, unpredictable beauty, and there’s man-made beauty, which is tools and machinery.”

Like landscape painters, van Woert’s sculptures often draw direct inspiration from the artist’s environment, but van Woert acknowledges that his immediate environment is urban, so he often makes art using materials like cleaning products and cat litter. Some of his work is an investigation of synthetic materials made to replace natural materials—like how cat litter is a manufactured substitute for soil.

“I have this running catalog of materials that we have made as replacements for natural ones,” he said. “If you want to go pee, you go pee outside in the dirt. But, we have cat litter.”

One sculpture in the exhibition is a chair made from plexiglass cases with different materials, including cat litter and pulverized plastic, layered like sedimentary rock in shifting, uncontrolled patterns. It’s an example of a man-made artwork that unexpectedly evokes the beauty of the natural world.

As an artist who investigates materials, van Woert has had misadventures with materials that have gone bad, specifically horror stories about exploding containers of domestic materials, like chlorine.

“I started to see the comfort these materials can provide as a camouflage for the violence underneath,” he said.

His work seems to comment on the different levels of value that humans place on materials—the disposability of domestic products, the volatility of plastics, or the often overlooked beauty of tree bark. His interest in materials is rooted in his architectural background.

“Buildings that were made a thousand years ago are still here,” he said. “Ones that were made 40 years ago aren’t here. We’re constantly driven to create these newer materials. … Plastic has a certain immortality to it. It will never die, but it’s not going to last as long as stone, probably. And we’re on a planet made of stone. It’s in no short supply.”

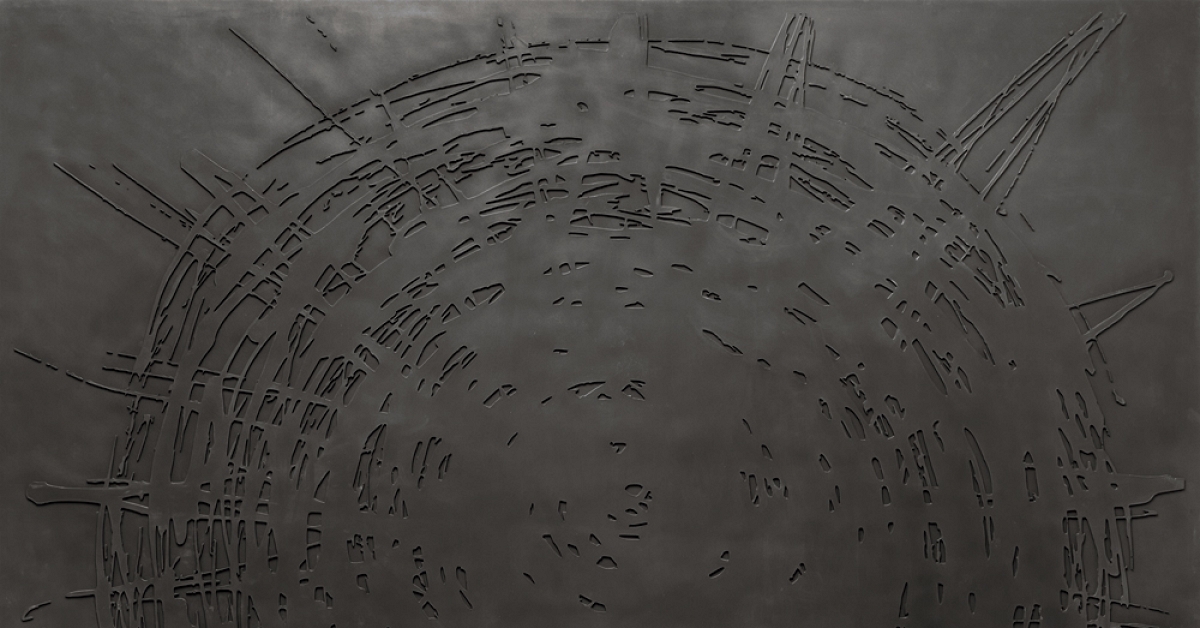

One sculpture is a nonfunctional steel recreation of van Woert’s pulverizer. It’s an object that was designed for strict utility, but van Woert sees beauty in the shape and geometry of the design. It’s a form of beauty that contrasts with and complements the other sculptures in the exhibition.

“It’s not supposed to be aesthetic, but there’s something about it,” he said. “It wasn’t designed to be beautiful; it was designed to serve a purpose, but there’s something so amazing about that. … With certain industrial machinery, there’s a beauty to it.”

The exhibition includes several large untitled sculptures. Most of van Woert’s work is an investigation of materials. He’s a sculptor, but he views his work as connected to the traditions of landscape painting—art that aspires to recreate the beauties of the natural world.

“There’s only two types of beauty, in a sense,” he said. “There’s natural beauty, which is this uncontrollable, unpredictable beauty, and there’s man-made beauty, which is tools and machinery.”

Like landscape painters, van Woert’s sculptures often draw direct inspiration from the artist’s environment, but van Woert acknowledges that his immediate environment is urban, so he often makes art using materials like cleaning products and cat litter. Some of his work is an investigation of synthetic materials made to replace natural materials—like how cat litter is a manufactured substitute for soil.

“I have this running catalog of materials that we have made as replacements for natural ones,” he said. “If you want to go pee, you go pee outside in the dirt. But, we have cat litter.”

One sculpture in the exhibition is a chair made from plexiglass cases with different materials, including cat litter and pulverized plastic, layered like sedimentary rock in shifting, uncontrolled patterns. It’s an example of a man-made artwork that unexpectedly evokes the beauty of the natural world.

As an artist who investigates materials, van Woert has had misadventures with materials that have gone bad, specifically horror stories about exploding containers of domestic materials, like chlorine.

“I started to see the comfort these materials can provide as a camouflage for the violence underneath,” he said.

His work seems to comment on the different levels of value that humans place on materials—the disposability of domestic products, the volatility of plastics, or the often overlooked beauty of tree bark. His interest in materials is rooted in his architectural background.

“Buildings that were made a thousand years ago are still here,” he said. “Ones that were made 40 years ago aren’t here. We’re constantly driven to create these newer materials. … Plastic has a certain immortality to it. It will never die, but it’s not going to last as long as stone, probably. And we’re on a planet made of stone. It’s in no short supply.”

One sculpture is a nonfunctional steel recreation of van Woert’s pulverizer. It’s an object that was designed for strict utility, but van Woert sees beauty in the shape and geometry of the design. It’s a form of beauty that contrasts with and complements the other sculptures in the exhibition.

“It’s not supposed to be aesthetic, but there’s something about it,” he said. “It wasn’t designed to be beautiful; it was designed to serve a purpose, but there’s something so amazing about that. … With certain industrial machinery, there’s a beauty to it.”