Artist x Artist: Mark Bradford and Samuel Levi Jones

Studio: The Studio Museum in Harlem Magazine / Jan 1, 2015 / by Naima J. Keith and Dana Liss

It’s been a big year for Samuel Levi Jones. The Bay Area artist was awarded the 2014 Joyce Alexander Wein Artist Prize, and will have his New York debut this spring in Samuel Levi Jones: Unbound at the Studio Museum. We invited his friend and mentor Mark Bradford to interview him at this exciting moment. Jones first met Bradford just over two years ago, when Jones was a newly minted MFA from Mills College in Oakland, California. Jones had been working with encyclopedias as a graduate student he found himself questioning the direction of his work, particularly his choice of material. Bradford encouraged him to continue his investigation of ency- clopedias—advice that the younger artist credits as instrumental to his practice today.

Mark Bradford: You were originally trained as a photographer, but now your work has evolved to disassembling objects such as encyclopedias and medical reference books. What precipitated your decision to change course? Do you view this transition as a change or continuation of your interests?

Samuel Levi Jones: The camera was an entryway into my art practice.”¨In college, I was introduced to the”¨35 mm film camera and became fascinated by the whole process of image- making—from composing through the viewfinder through creating the silver print in the darkroom. Even though my recent work has evolved from photographed images to images created from other materials, the process is definitely a continuation of how I previously executed my work. Throughout this journey I have always created as a reaction to personal ideas and experiences within and around me. As my ideas have progressed, it has become necessary to find new materials, and techniques to work with them in an authentic way. The camera no longer serves my current process. It is my intention to work with the best possible medium to express what is going on in my head.

MB: What is your relationship to these objects? For example, did you grow up with encyclopedias?

SLJ: I grew up using encyclopedias for research. I specifically remember using them in junior high school. I remember these reference books being considered a true source for information, and that some other forms of source material were considered illegitimate. In my use of encyclopedias, I am considering the vast amount of information that never makes it into these objects. Yes, there is a great deal of informa- tion in them, but there is also an entire world of knowledge that is excluded. Through my making I am thinking about the existence of this construct and the cultural ramifications of how we respond and react to it.

MB: How has your relationship to the materials you work with changed upon further investigation and work? If so, what was most significant for you?

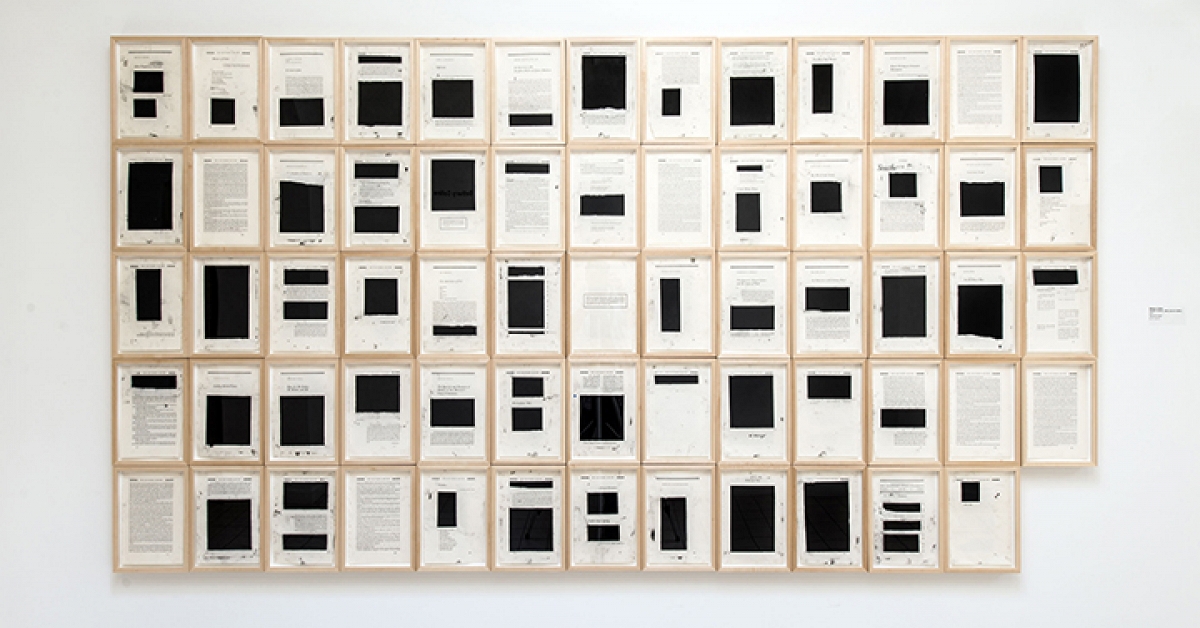

SLJ: In my initial investigation of the encyclopedia during graduate school, I was thinking about the power of the encyclopedia and its reputation as a complete source of information about the world we live in. In the process of flipping through each and every page of this first set of books, I became un- settled. I began removing the formal portraits from each page to create visual juxtapositions between high and low representation. This led to 736 Portraits and 48 Portraits (underexposed) (both 2012). As I was working with only one, black-and- white encyclopedia set, 736 Portraits and 48 Portraits (underexposed) are without color. It was not too long after school that you and I met, and you questioned where I was going with my work. I mentioned that I was considering a complete departure from the encyclopedia material. You challenged me to stick with it and dig deeper. I quickly realized the rich versatility of the material once I began further deconstructing the books. The deeper investigation that came from pushing myself to stay with it has been the most significant part thus far—not allowing myself to settle for one layer of discovery, but rather continuing to ask questions and looking for answers within.

MB: How do you source your materials and what is your process?

SLJ: A good deal of my material is found via the web. I recently completed a residency at a waste- management facility in San Francisco called Recology. All the material that I used for the work I created there was reclaimed from someone’s trash. I still acquire a lot of my material through purchase, but there is a great deal of it out there that is being discarded. My process consists of breaking down the source material then reconstructing it into some- thing visually interesting in order to generate dialogue about the original material itself.

MB: Your work starts with found materials (encyclopedias, reference books, etc.), which are then trans- formed and abstracted. What would you say about the push-and-pull that exists between the abstract and figu- rative elements in your work?

SLJ: Visually the work is abstract, but the materials are very concrete. I feel the abstraction is a way of challenging the viewer to spend time with the work and the ideas. I attempt to create the work in such way that the viewer can’t approach it with an immediate reaction of, “Oh, books,” but rather have a many-layered experience. In 48 Portraits (underexposed), I have observed viewers looking at the grid and thinking they are seeing only black squares. Only after they are encouraged to spend more time with the work do they find the figures. The push-and-pull for me is about challenging people to slow down the process of experience, and to look and question.

MB: How does your use of the modernist grid format relate to your materials’ content? If the modernist grid declares the autonomy of art, do you see your work in any way removing its source material from the social realm?

SLJ: For the most part, the shapeӬof the material lends itself to a grid format. In some of the most recent work I have broken the material down further to get away from the grid a little. These works that do not fall into a grid format are simply about pushing the work visually. The conceptual process of breaking down the material is cathartic, and the reconstruction is more playful.

MB: You are an emerging artist who has just been awarded the Wein Prize. How has this newfound recognition affected your work? Has your notion of your personal success changed or evolved over your career, and does it continue to do so?

SLJ: The recognition has definitely pushed me to challenge myself more and with greater enthusiasm. I feel that it has created a deeper ambition to continue challenging myself to push my work. My notion of personal success has been changing for a long time. I feel as though I have navigated my journey without particular long- term expectations. That is not to say that I have not challenged myself to achieve some sort of success. I just didn’t know the area in which that success would manifest. I would say that my expectations have evolved. My passion for art did not begin until I was twenty-three. When I moved from Indiana to California for graduate school, my expectation was to have a career teaching photography at a university. I had little understand- ing of what it meant to be a successful practicing artist, or that I would even exist within that context

.

2014 Joyce Alexander Wein Artist Prize: Samuel Levi Jones

On October 27, 2014, Studio Museum Director and Chief Curator Thelma Golden awarded the ninth annual Joyce Alexander Wein Artist Prize to Samuel Levi Jones. The Wein Prize, one of the most significant awards given to individual artists in the United States today, was estab- lished in 2006 by jazz impresario, musician and philan- thropist George Wein to honor his late wife, a longtime Trustee of the Studio Museum and a woman whose life embodied a commitment to the power and possibilities of art and culture. Inspired by his wife’s lifelong support of living artists, George Wein envisioned the Wein Prize as an extension of the Studio Museum’s mission to sup- port experimentation and excellence in contemporary art. The $50,000 award recognizes and honors the artis- tic achievements of an African-American artist who demonstrates great innovation, promise and creativity.

Samuel Levi Jones was born and raised in Marion, Indiana. Trained as a photographer and multidisciplinary artist, he earned a BA in Communications Studies from Taylor University and a BFA from the Herron School of Art and Design in 2009. In 2012 he completed his MFA in Studio Arts from Mills College, Oakland, California.”¨He currently works and resides in the San Francisco Bay Area. Jones’s work is informed by historical source material and early modes of representation in documentary practice. He explores the framing of power by desecrating historical material and then reimagining new works. Jones investigates issues of manipulation and the rejection of control.

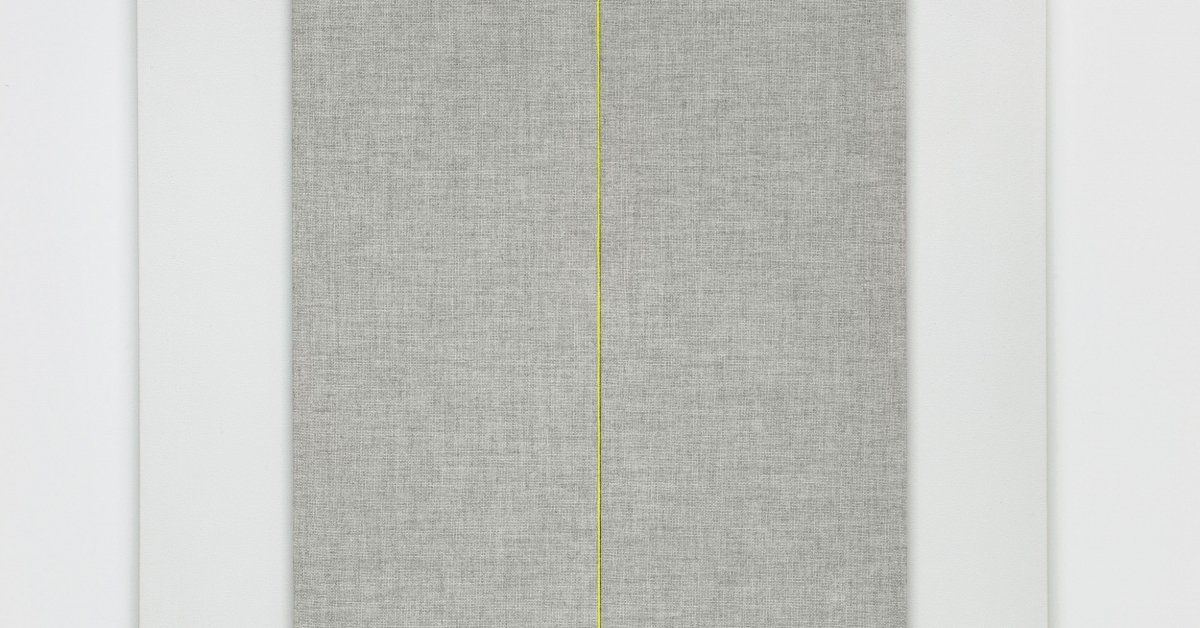

Building upon the themes found in his earlier work, Jones’s work currently consists of deconstructing found encyclopedias as a means of creating a medium that communicates a feeling of being on the outside, as well as to provide a possible resolution to the search, of an outsider, for a place of inclusion and identity. By literally tearing apart these books—widely published arbiters”¨of authenticity—and reconstructing them into abstract two-dimensional works for the wall, Jones is able to forge a more personal alliance with the materials. It is through this intimate exploration of the materials that Jones”¨is able to delve deeper into his behavior and practice”¨of omission as he removes and fractures information.

Jones recently completed the Recology Artist in Residence Program in San Francisco, which concluded with a group exhibition. He has been featured in several group shows in California, including The Histories of Technologies (Jessica Silverman, 2014), Open (PAPILLION, 2014) and TRANSPORT…Where we go from here (Pro Arts, 2013). His work has been exhibited in the Latent Image Gallery, Indianapolis; the Cal State University Gallery;”¨the Branch Gallery, Oakland; the Herron School of Art and Design, Indianapolis; Mills College, Oakland; the Watts Towers Art Center, Los Angeles; and PAPILLION, Los Angeles. His solo exhibition, Black White Thread, was on view at PAPILLION from November 8, 2014, to January 4, 2015. A solo exhibition showcasing his very first site- specific work will be on view at the Studio Museum from March 26 to June 28, 2015.