At SFSU, Looking and Truly Seeing the Middle East Through Art

KQED Arts / Mar 9, 2017 / by Roula Seikaly / Go to Original

What does it mean to look? And what does it mean to be seen?

These are two of the critical questions raised in Mashrabiya: The Art of Looking Back, an intimate, six-person exhibition now on view in the San Francisco State University (SFSU) Fine Arts Gallery.

The title Mashrabiya refers to the projecting latticed windows that are a familiar feature of domestic architecture throughout the Middle East and wider Islamic world. The windows function to protect inhabitants — primarily women — from public gaze while simultaneously providing a safe vantage point from which to view the public realm. Co-curators Santhi Kavuri-Bauer, Kathy Zarur, Sharon E. Bliss and Mark Johnson adapted the mashrabiya as a visual metaphor through which to think about social and political relations between East and West, and how much the West in particular has yet to learn.

Taraneh Hemami’s Bulletin, published in conjunction with the longform project Theory of Survival, establishes a loose context for the overall exhibition. Comprising critical points in Iranian and world history, Bulletin offers a more complete account of the country’s fraught passage through the 19th and 20th centuries, widening the otherwise narrow aperture through which Middle Eastern life is perceived.

Iran’s history does not begin with the Islamic Revolution (1978-79), but that is the primary event that informs almost all contemporary media portrayals of the country to this day. Hemami’s bulleted list, mirroring a mashrabiya in its layout, situates her native country and other Middle Eastern nations within the temporal spectrum of recent history to illustrate how little we know of a place otherwise relegated to “the axis of evil.”

While no two stories about living outside one’s cultural and familial context are the same, certain themes emerge in The Art of Looking Back that create a cohesive exhibition narrative; namely mistranslation and the consequences of war.

Los Angeles-based Sherin Guirguis addresses cultural appropriation through painting and sculpture. In Untitled (ollas), Guirguis models unglazed ceramic water jugs in wood and modifies them with gold-painted, geometric wings. The wings enhance the curvaceous white vessels, and render them useless as functional objects.

Like so many non-Western objects that come into public or private art collections through legal and extralegal means, any appreciation of their aesthetic appeal is tempered by their dislocation from their original use and context. Guirguis’ modification of the jugs gestures to the mono-directional flow of cultural items from East to West under European colonialist rule and the tendency to regard, or “see” Arab and Persian cultures, as permanently moored to antiquity, unable to evolve.

Though the United States did not indulge in Middle Eastern colonialist misadventures as our European counterparts did, we’ve supported or lead multiple disastrous military incursions into the region. Those actions, like all actions, have consequences, and the work in The Art of Looking Back gestures to those negative influences.

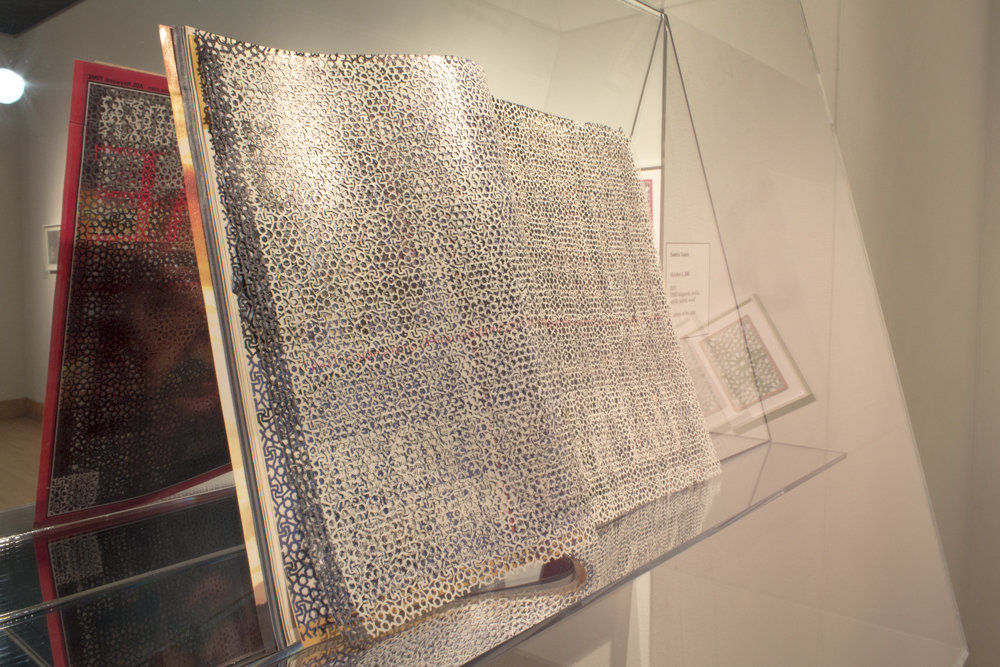

Samira Yamin works with modest, mass-produced pulp paper, carving the repetitious geometric forms that make up mashrabiyas. Cutting each page by hand, she reveals an obsessive aspect to her practice. While the volumes of Time magazine she modifies don’t exclusively address the twin catastrophes of war in Iraq and Afghanistan or the Sept. 11 attacks, those events aren’t far away, and Yamin’s exquisite paper screens further emphasize the power of media to obfuscate comprehension.

Sanaz Mazinani, whose solo exhibition Signal to Noise is concurrently on view at SF Camerawork, creates an installation at SFSU of floor and wall-mounted mirror panels onto which she projects abstracted scenes of destruction from popular American films. The sumptuous, atmospheric experience is tempered by the knowledge that what we import from the Middle East is decidedly less deadly than what we export to the region.

Before the two-fronted war and the calamity of ISIS it unleashed, the United States’ relations with Middle Eastern countries were precarious at best, perpetually clouded by differences in language, religion, and culture. In 2017, we are no closer to understanding one another and may, if the current administration’s ill-conceived travel ban is any indication, be further from mutual comprehension than ever been before. But Mashrabiya: The Art of Looking Back also celebrates the establishment of a center for Iranian diasporic studies at SFSU in the coming year. This news and the group exhibition on view offer a tentative path toward understanding, toward seeing civilizations other than our own for the depth, beauty, and complexity that define them.