Becoming The Breeze

The Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago / Sep 24, 2020 / by Jack Schneider and Raven Falquez Munsell / Go to Original

This digital brochure was published on the occasion of the exhibition Becoming the Breeze: Alex Chitty with Alexander Calder, organized by Raven Falquez Munsell, independent curator, and Jack Schneider, MCA Curatorial Assistant, in collaboration with Alex Chitty and with the support of MCA staff. It was presented from November 16, 2019 to March 13, 2020, in the McCormick Tribune Gallery on the museum’s second floor.

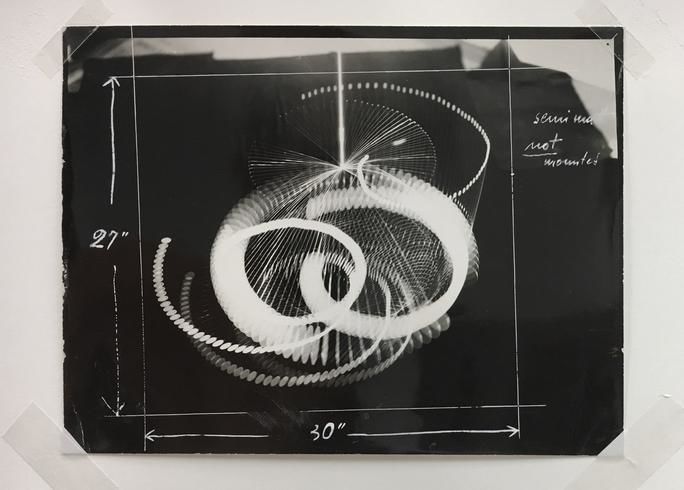

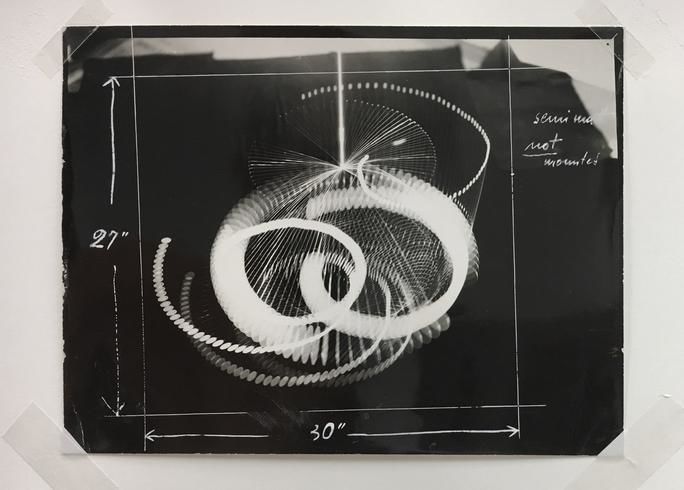

Herbert Matter (American-Swiss, 1907-1984), Alexander Calder hanging mobile in motion (1936)

Herbert Matter (American-Swiss, 1907-1984), Alexander Calder hanging mobile in motion (1936)

Alexander Calder’s (American, 1898–1976) mobile sculptures were made to move. In the 1930s photographer Herbert Matter (American, b. Switzerland, 1907–1984) captured Calder’s work in feverish, exaggerated motion. Using dramatic lighting and long exposures, Matter revealed the dynamic spirit of Calder’s artwork. With his camera he captured the mobiles’ motion over time as they created layered and interlaced trails of lights—a ghostly dance. But Matter was not the only artist to make Calder’s sculptures dance. Multiple experimental films were made, sets designed, and more recently, exhibitions curated to highlight the intended fluidity, motion, and spirit of Calder’s work.

The notion of movement was the genesis of the exhibition Becoming the Breeze: Alex Chitty with Alexander Calder at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (MCA). For artist Alex Chitty (American, b. 1979), the Calder sculptures and their potential movement became a salient metaphor for how one can inquisitively engage the social, political, and interpersonal forces in our lives—and, by extension, how one chooses to be in the world.

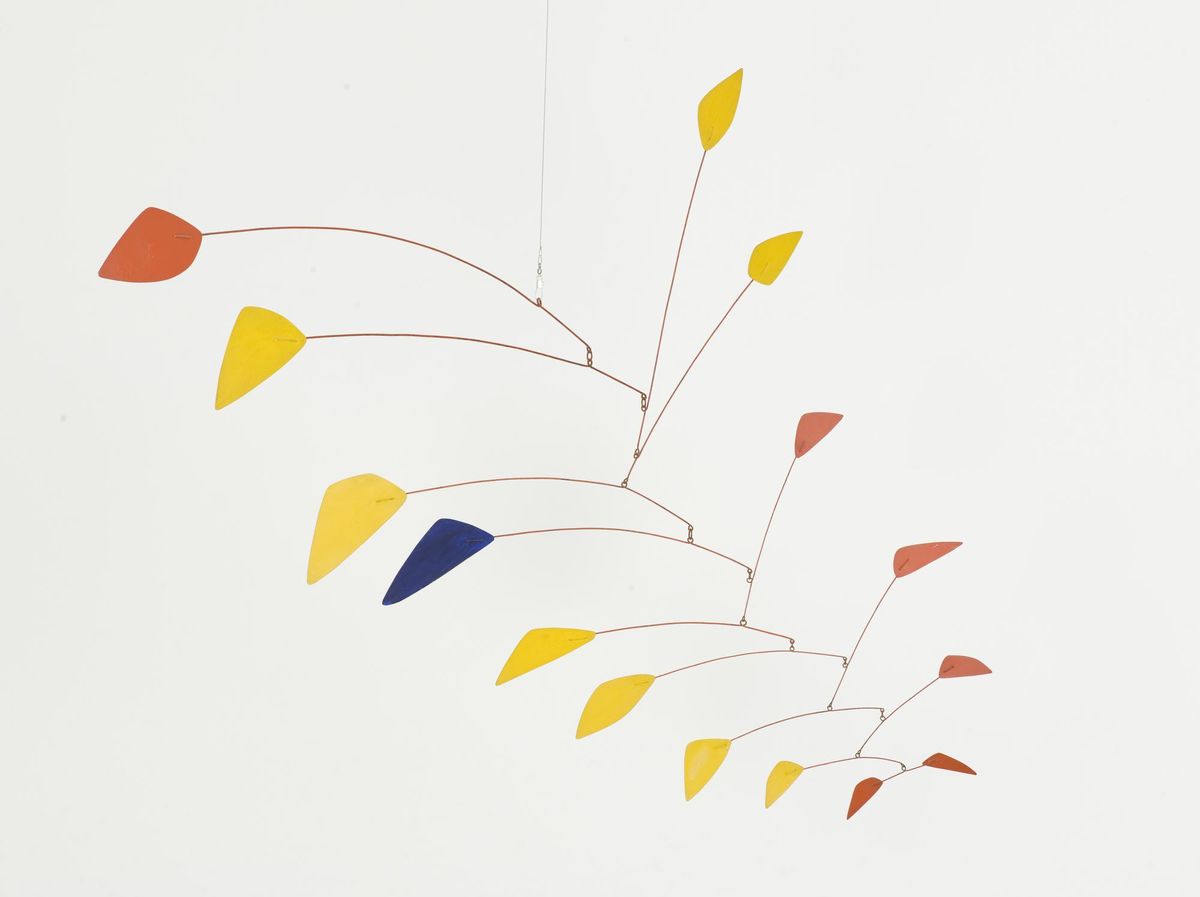

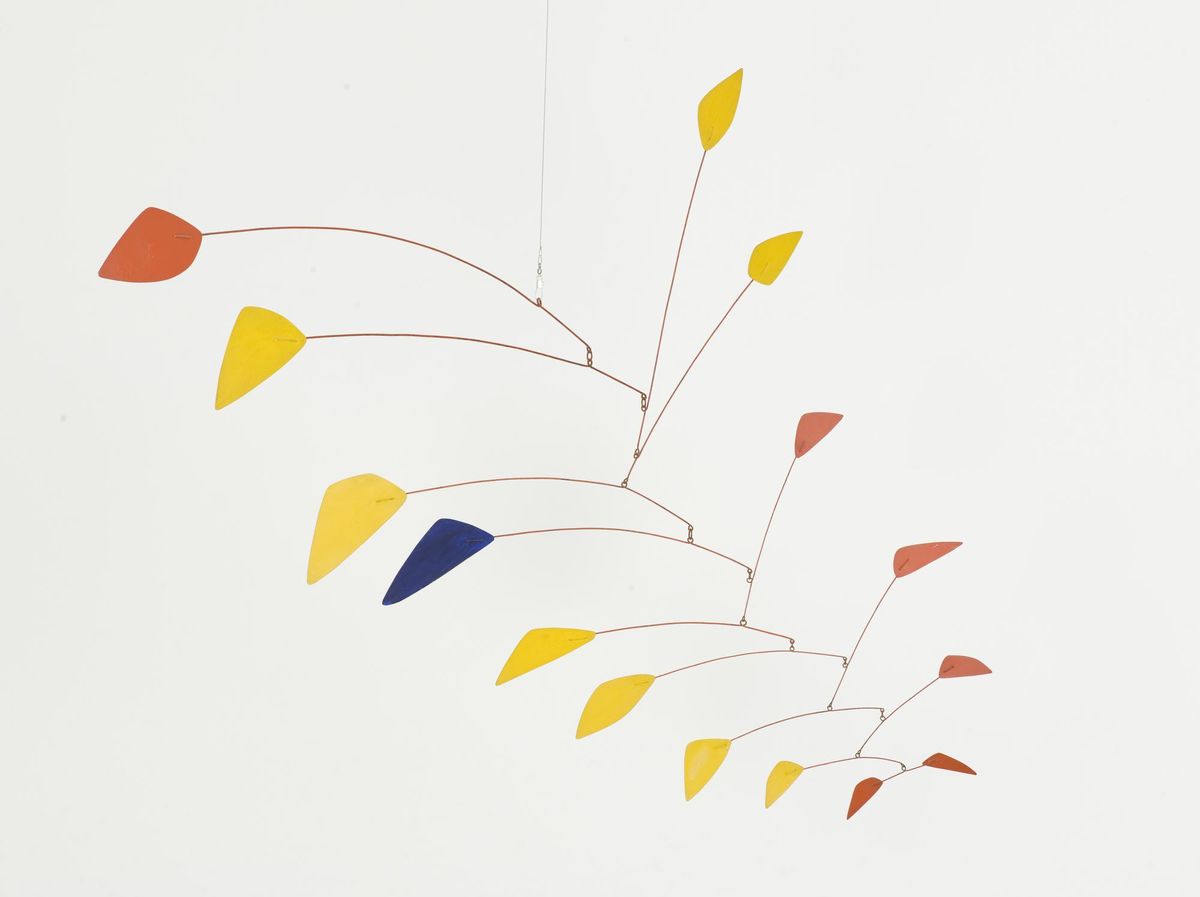

As visitors enter the MCA, one of the first things they encounter is an uncanny sight: what appears to be a frenetically spinning mobile by Alexander Calder. The mobile’s movement, almost frantic in comparison to its usual languid rotation, is driven by a motorized fan mounted on the adjacent wall. The work is, in fact, not one of Calder’s mobiles, but a replica of his Blue Among Yellow and Red (1963), made by Chitty. Titled Zeebo in they house (2019), Chitty’s stunt-double mobile greets visitors outside of the gallery space and introduces the framework for her exhibition and artistic intervention at the museum. With this work, Chitty validates the commonly held desire to see Calder’s mobiles move and importantly asks museum visitors to take a second look at what they are seeing.

Alexander Calder Blue Among Yellow and Red (1963), Alex Chitty created a replica of this artwork for Becoming The Breeze.

Alexander Calder Blue Among Yellow and Red (1963), Alex Chitty created a replica of this artwork for Becoming The Breeze.

Both Matter and Chitty brought their own creative vision to Calder’s artworks. It is this crossroads of artistic and curatorial practice—activating the works of one artist with the vision of another—that is the vital work of the artist curator. Becoming the Breeze is part of a rich history of artist-curated exhibitions and artist-led interventions into museum collections.

This history begins with Andy Warhol’s exhibition Raid the Icebox (1969–70), which is credited as the first artist-curated museum exhibition. At the time of the exhibition, the Rhode Island School of Design Museum (RISD Museum) had found itself in an unfortunate state of financial duress, and Warhol was invited to uplift the stagnating collection. In selecting objects for the exhibition, Warhol overlooked many of the museum’s better-known and cherished holdings, such as their costume collection and fine furniture by 18th-century Rhode Island craftspeople. He instead favored their lesser-known and peculiar holdings, such as their collection of shoes and umbrellas. In all, Warhol selected roughly 400 objects from the museum’s collection, ranging from paintings to Native American pottery to wallpaper. By presenting the lauded objects from the collection alongside those considered to be average or unremarkable, Warhol challenged the notion that any single object in the collection had greater value or importance than another. Writing on the exhibition, curator Anthony Huberman notes that Warhol “recognized that there is no such thing as an ‘ideal’ or even ‘good’ or ‘bad’ collection, collector, or collecting institution,” and that the artist’s intention was to “flatten and nullify the playing field so as to render bankrupt the very notion of winners and losers.

Installation view of Andy Warhol’s exhibition Raid the Icebox at the Rhode Island School of Design Museum, 1969

Installation view of Andy Warhol’s exhibition Raid the Icebox at the Rhode Island School of Design Museum, 1969

The manner in which Warhol exhibited the collection further reinforced this subversion of museological and curatorial convention. Rather than following standard museum display methods, Warhol insisted that the works be shown in the galleries just as they existed in storage: in stacks against the walls, on cluttered shelves and racks, and in cellar-like dim light. The project aligned with Warhol’s broader artistic ethos, which disrupted hierarchical distinction between high and low culture by championing the ordinary, the overlooked, and the everyday. Warhol’s seemingly cavalier display strategy was unsettling at the time, in particular to the museum directors, as it not only challenged the authority of the museum curator, but it also very clearly revealed the lack of funding and organization befalling the museum’s collection, as evidenced by their disorderly storage practices and facilities.

In Becoming the Breeze, Chitty similarly chose to display several of Calder’s works as she had encountered them in storage during her research visits to the MCA. Calder’s bronze sculpture A Detached Person, for example, is shown disassembled, as it would be stored, as is his mobile Black: 17 Dots (1959), which is shown tied into its custom storage tray. Furthermore, Chitty’s sculptural structure Alex (linked), on which several works by Calder are displayed (including Orange Under Table [c. 1949], Performing Seal [1950], Black: 17 Dots, A Detached Person [1944/1968], and Chat-Mobile [1966]), was made using repurposed metal shelving units that reference what is used in the MCA’s storage facilities. Like Warhol, Chitty was moved by what happens backstage and wanted to share with the public what is not normally seen in the museum galleries. In Warhol’s case, this dignified ordinary and forgotten objects in the collection; for Chitty, it elevated the careful work of museum employees to assert that their care of the artwork is as important as the artwork itself.

Installation view of Alex (linked) (2019) featuring Alexander Calder’s Black: 17 Dots (1959) and A Detached Person(1944/1968)

Installation view of Alex (linked) (2019) featuring Alexander Calder’s Black: 17 Dots (1959) and A Detached Person(1944/1968)

Alexander Calder’s Black: 17 Dots (1959) in the MCA’s storage facility. Photo: Raven Falquez Munsell

Alexander Calder’s Black: 17 Dots (1959) in the MCA’s storage facility. Photo: Raven Falquez Munsell

Alexander Calder’s A Detached Person (1944/1968) disassembled

Alexander Calder’s A Detached Person (1944/1968) disassembled

This consideration for the work of museum employees is also revealed through Chitty’s photographic diptych Precedence (2019). Two photographs depict the installation process of Calder’s mobile The Ghost (maquette) (1964), in which three of the museum’s preparators are shown gently raising the sculpture out of its storage tray for installation in the same atrium. These three technicians are only a fraction of the behind-the-scenes staff at the museum working to produce exhibitions. Chitty’s photographs elevate them and the work that they do—work that, when done well, is meant to be invisible. The Ghost (maquette) was installed on a hook and wire in the ceiling, which Chitty asked to be left behind as part of the exhibition. The hardware hangs from the ceiling, spot lit and titled The Ghost (Louisa) as a nod to Calder’s wife, Louisa, and all of the invisible partners and collaborators that work to support the creative process.

Alex Chitty, Precedence, 2019. Archival inkjet prints and artist’s frame. Courtesy of the artist and PATRON.

Alex Chitty, Precedence, 2019. Archival inkjet prints and artist’s frame. Courtesy of the artist and PATRON.

Beyond revealing the many unseen institutional processes required to produce a museum exhibition, Chitty also reveals how artworks are made—how they come to be in the world. Chitty’s practice is most recognizable by her expert craftwork and her unwavering invitation to look (and to spend time looking) at her peculiar compositions and materials. For the sculpture of Alex (linked), however, Chitty opted for a different, less polished approach. She left exposed the raw welded corners of the repurposed shelving units, as well as measurements written in black marker on the surface of the work. Just as she revealed the inner workings of the museum, Chitty left behind these subtle gestures, like breadcrumbs intended to lead viewers through her artistic process. As with the crop-marks made visible on the aforementioned photographic diptychs, Chitty included other clues: the sharpened nub of a #2 pencil, jammed in place as if to level a piece of shelving, a portion of a wooden log that holds up part of the structure displaying Calder’s Black: 17 Dots. With these moves, Chitty goads the viewer, encouraging them to ask questions about whether these traces are intentional or left behind in haste. As an artist whose practice toggles between object making and image making, Chitty applied her own studio logic to Calder’s historical works, each time pushing the viewer to question what they are seeing.

Alex Chitty, Alex (linked) (detail), 2019

Alex Chitty, Alex (linked) (detail), 2019

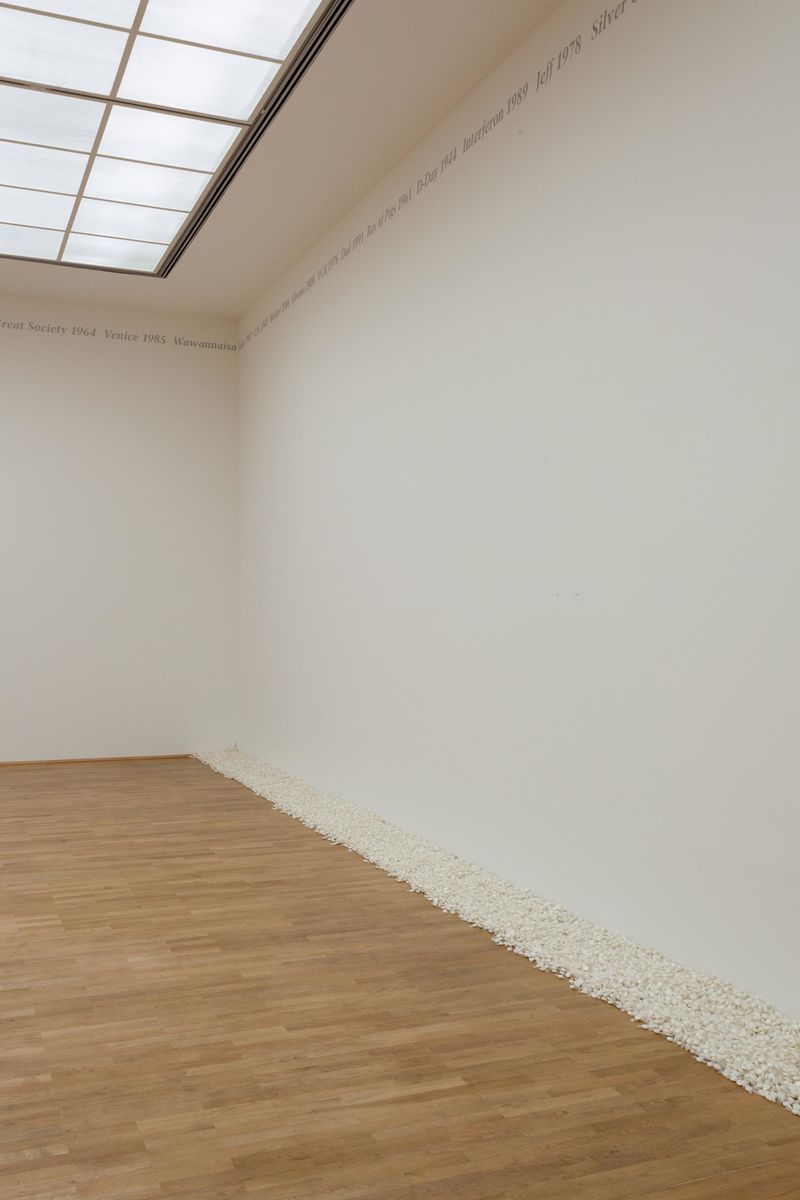

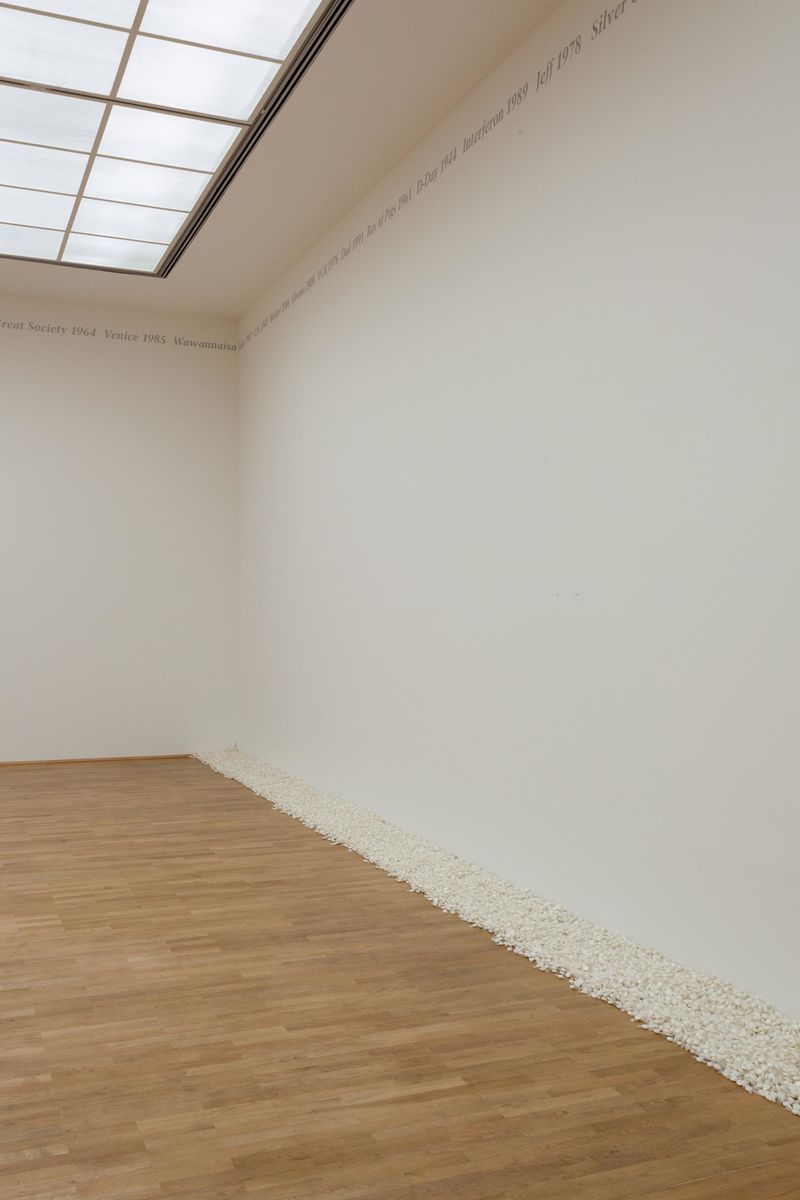

While Warhol’s approach sought to engage the RISD Museum’s collections in surprising new ways,other artist-driven exhibitions have taken a more intimate approach: enlisting artists to engage the work of another singular artist. One recent example is Specific Objects Without Specific Form (2016). For the traveling show, organizing curator Elena Filipovic invited three contemporary artists—Carol Bove (Swiss, b. 1971), Danh VÅ (Danish, b. 1975), and Tino Sehgal (German, b. 1976)—to co-curate exhibitions of works by Felix Gonzalez-Torres (American, b. Cuba, 1957–1996) at three different venues. Gonzalez-Torres’s conceptual artworks often exist as sets of instructions or parameters for installation that are described in an accompanying certificate of authenticity. The works are not discrete objects kept in storage, but rather are manifested anew each time they are exhibited. As an example, the certificate for Gonzalez-Torres’s “Untitled” (Portrait of Dad) (1991) specifies that the work consist of 175 pounds of white candies individually wrapped in cellophane; however, the particular shape that the mass should take is not specified. The artist originally displayed this work piled in the corner of a room; consequently, this shape and placement has become the implied museum standard. Gonzalez-Torres’s lack of specification for the shape was deliberate, as he intended for this aspect of the work to be open to interpretation. At each of its three venues, Specific Objects Without Specific Form operated like a game of round robin. First, Filipovic installed Gonzalez-Torres’s work, then, halfway through the exhibition’s run, one of her artist co-curators would reinstall the exhibition, often altering the manifestation of Gonzalez-Torres’s artworks in the process. In the iteration at Fondation Beyeler, Filipovic initially installed “Untitled” (Portrait of Dad) in a rectangle on the floor; later Carol Bove re-interpreted the work by simply turning that rectangular pile ninety degrees. The same work at the Museum für Moderne Kunst was installed two different ways by Tino Sehgal: first as a pile in a corner and later along the edge of a wall. By challenging traditional institutional exhibition formats, Filipovic, Bove, VÅ, and Sehgal foregrounded the underemphasized malleable nature of Gonzalez Torres’s work.

A manifestation of Felix Gonzalez Torres’ “Untitled” (Portrait of Dad) at Specific Objects Without Specific Form at the MMK Museum Fur Moderne Kunst, 2016

A manifestation of Felix Gonzalez Torres’ “Untitled” (Portrait of Dad) at Specific Objects Without Specific Form at the MMK Museum Fur Moderne Kunst, 2016

A manifestation of Felix Gonzalez Torres’ “Untitled” (Portrait of Dad) at Specific Objects Without Specific Form at the MMK Museum Fur Moderne Kunst, organized by Elena Filipovic and Tino Sehgal

A manifestation of Felix Gonzalez Torres’ “Untitled” (Portrait of Dad) at Specific Objects Without Specific Form at the MMK Museum Fur Moderne Kunst, organized by Elena Filipovic and Tino Sehgal

Working in a mode similar to Fillipovic and her artist co-curators, Chitty also explored the ambiguities of a document that governs the display of Calder’s artworks at the MCA: the Horwich Family Loan. While most of the Calder artworks in the exhibition are not part of the MCA Collection, they are nonetheless an important part of the museum’s history, having been cared for and exhibited at the museum for 25 years. In 1995, founding MCA members Ruth and Leonard Horwich initiated a long-term loan of fifteen artworks by Alexander Calder to the museum. Since then, a portion of the artworks from the original loan have been gifted by the family, becoming part of the museum’s permanent collection. The remaining works in the loan are subject to its terms that mandate that, so long as they are under the care of the museum, they must be on view most of the time. In Becoming the Breeze, Chitty considered this directive in numerous ways— her project questions the terms of the loan and whether it can be satisfied if the artworks are shown as photographs, facsimiles, or in silhouette as with Calder’s Performing Seal (1950).

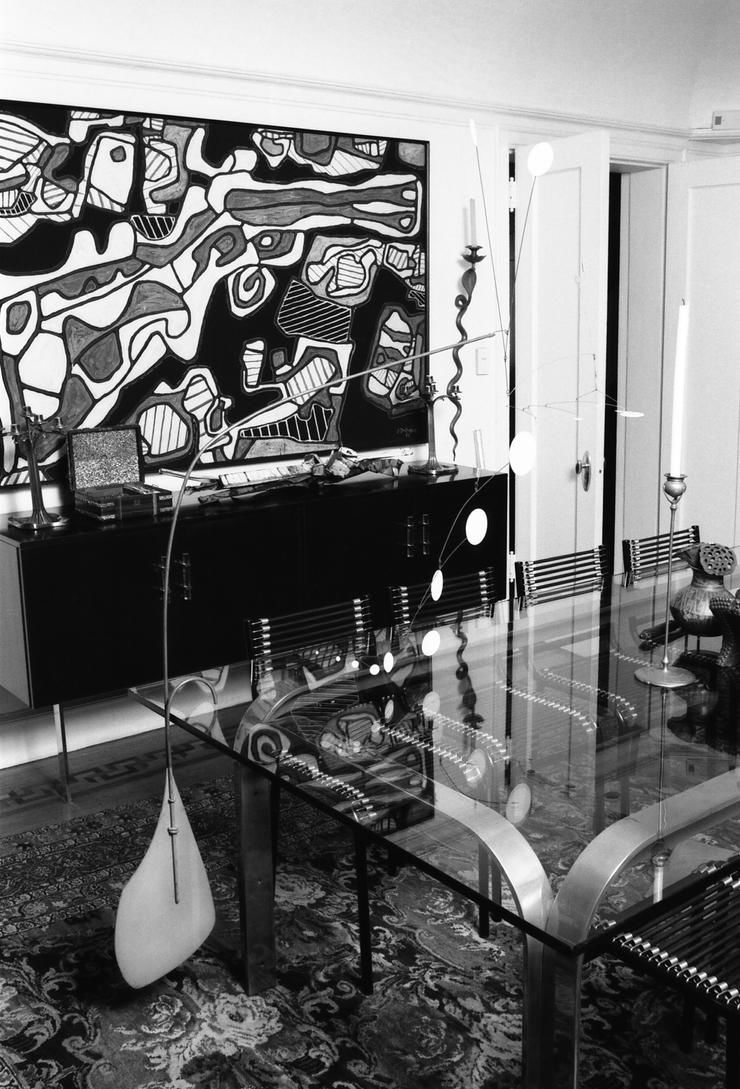

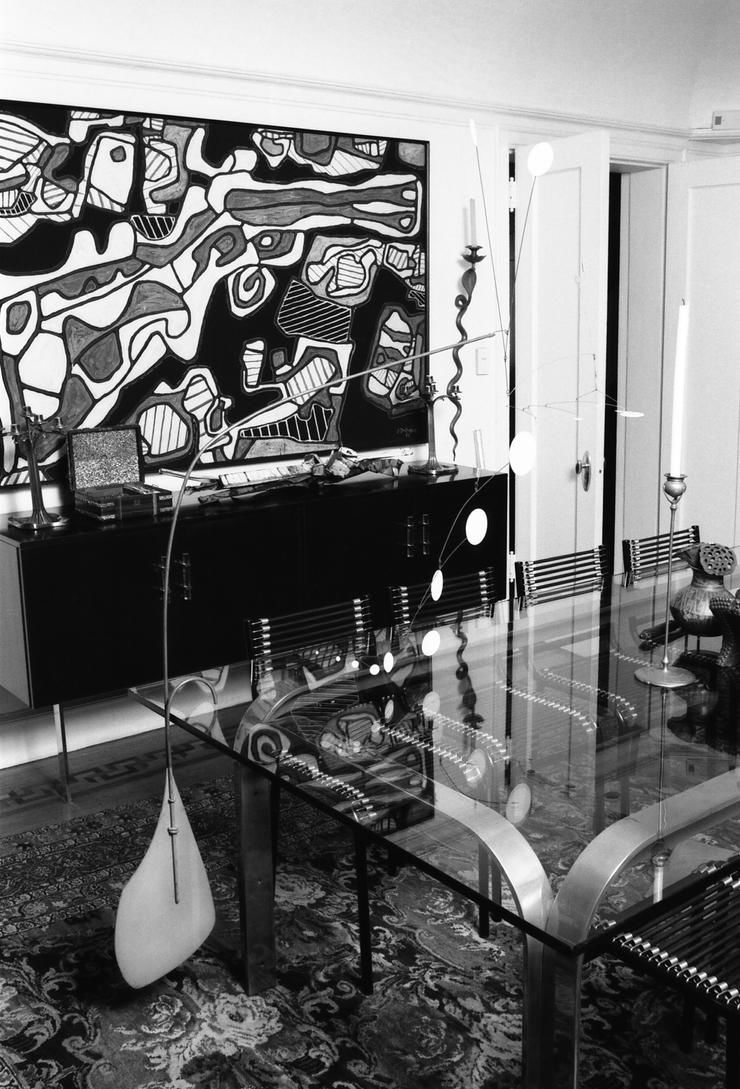

In this exhibition, Chitty carefully considered the history and provenance of each artwork, sometimes incorporating this history in its display. In her presentation of Calder’s Orange Under Table (c. 1949), Chitty nodded to the peripatetic nature of artworks by linking the work to its owners, the Horwich Family. The glass table on which the sculpture is displayed is a near-copy of the table in the Horwich’s dining room, where the sculpture lived before moving to the museum. Photographs of the Horwich’s home reveal how they cohabitated with the artworks in their collection, Orange Under Table held a prominent place, sitting at the head of their dining table as if it were a stand-in for the host. Chitty acknowledged this important history of the artwork’s provenance and installation in the lender’s home in her reinterpretation. In this way, she not only recalled the movement of Calder’s work through time and space, but also emphasized the partnerships between private parties and public institutions that are at the foundation of many museums.

Home of Life Trustee Ruth Horwich, 1992.

Home of Life Trustee Ruth Horwich, 1992.

Work shown: Alexander Calder, Orange Under Table, c. 1949. Sheet metal, paint, metal rods, and steel wire; 72” × 82” diameter (182.9 × 208.3 cm diameter).The Leonard and Ruth Horwich Family Loan, EL1995.11

Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago, © 2019 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Installation view of Alex (linked) (2019) featuring Alexander Calder’s Orange Under the Table (c. 1949) and Performing Seal (1950) in Becoming the Breeze: Alex Chitty with Alexander Calder

Installation view of Alex (linked) (2019) featuring Alexander Calder’s Orange Under the Table (c. 1949) and Performing Seal (1950) in Becoming the Breeze: Alex Chitty with Alexander Calder

As Becoming the Breeze continues in the lineage ofartist-curated exhibitions, several other museums in the United States have concurrently invited artists to intervene in their collections. Of particular relation and resonance to the MCA’s exhibition is Brendan Fernandes: Contract and Release. In this exhibition, Brendan Fernandes (Canadian, b. Kenya 1979) augmented Noguchi: Body-Space Devices, an exhibition at the Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum in New York. Body-Space Devices includes selected works from the permanent collection that demonstrate sculptor Isamu Noguchi’s (American, 1904–1988) interest in engaging the body.

Noguchi’s work in sculpture and design was deeply tied to movement and the relationship between viewers, objects, and space. His sensitivity to the human body in his work is pushedfurther by Fernandes’s engagement with it. Stage props Noguchi created for Martha Graham’s (American, 1894–1991) dance performances sit prominently within the exhibition; a rocking chair Noguchi made for the 1944 production of Appalachian Spring was of particular interest to Fernandes, a multi-disciplinary artist and trained dancer. Fernandes took the conceit of Body-Space Devices and augmented it with his own artworks, as well as with weekly dance choreographies. He reinterpreted Noguchi’s 1944 rocking chair and designed six alternative versions to serve as training tools and props for the dancers in his performances.

Brendan Fernandes: Contract and Release at the Noguchi Museum, 2019

Brendan Fernandes: Contract and Release at the Noguchi Museum, 2019

Brendan Fernandes: Contract and Release at the Noguchi Museum, 2019

Brendan Fernandes: Contract and Release at the Noguchi Museum, 2019

Like Chitty, Fernandes worked with the particular constraints of an institution and its objects. As withCalder’s mobiles, which viewers are prohibited from activating, Noguchi’s sculptures in the museum are not to be touched. For Contract and Release, Fernandes’s dancers climb and slide along the curves of Noguchi’s Play Sculpture (c. 1965), a large-scale red sculpture inside the exhibition intended for outdoor display. In another gallery of the museum, the dancers carefully disassemble and move wooden copies of Noguchi’s bronzes made by the museum’s production team. But these copies were not originally intended for public display: the wooden maquettes were made as an internal teaching tool for the museum’s preparators to practice the gentle assembly of Noguchi’s works. Here Fernandes brings the behind-the-scenes work to the fore. Similar to how Chitty revealed the complexities of Calder’s artworks with her display of A Detached Person, or the photographic diptych Precedence, Fernandes offered museum visitors an understanding of the interlocking, puzzle-like construction of Noguchi’s bronzes with his interventions.

Where Fernandes used the framework of dance to activate Noguchi’s work, Chitty used sculptural interventions to do the same with Calder’s work. This strategy is most evident in Chitty’s re-presentation of Calder’s A Detached Person. A Detached Person (1944/1968) consists of five distinct bronze pieces that stack and balance on one another to form a seated figure. Materially, this series represents an anomaly in Calder’s career, and yet it reveals his process in ways that other works of his do not. The range in date marks the continuum of this practice: 1944 is when the plaster or clay body was made, and 1968 when he was able to cast the works in bronze. Then, as told by the artist himself in his biography, the decision to abandon this

material as it had been considered by his gallery a commercial failure. The artist’s practice, economic concerns, and pressure to perform within the market are all embodied within this one work. For this reason the sculpture, as well its title, served as a fitting conveyance for Chitty to reflect on what it means to be an artist working today.

Alexander Calder’s A Detached Person (1944/1968) assembled.Courtesy of the artist and PATRON Gallery, Chicago

Alexander Calder’s A Detached Person (1944/1968) assembled.Courtesy of the artist and PATRON Gallery, Chicago

Installation view, Alexander Calder’s A Detached Person (1944/1968) shown disassembled on Alex Chitty’s Alex (linked) (2019)

Installation view, Alexander Calder’s A Detached Person (1944/1968) shown disassembled on Alex Chitty’s Alex (linked) (2019)

In the MCA exhibition, A Detached Person is presented on a display shelf made of industrial shelving and a retired shipping crate. Each constituent bronze piece sits or balances on a different level of the display structure—inspired by the work of mid-century designer Charlotte Perriand (French, 1903–1999)—in ways that indicate the balanced construction of Calder’s sculpture. Here Chitty’s audience has to visually reconstruct the piece, understand its stacking components, and look intently to understand the work as a whole. But beyond pushing her audience to do the work of mentally assembling the piece, the purposefully scattered bronze pieces are meant to reflect the imbalance of labor in the arts today. In a competitive, saturated, and infamously undercompensated industry, artists, curators, administrators, preparators, critics, writers, and educators lead a multihyphenate existence as a means for survival—each one moonlighting in different parts of the industry to produce the rich culture that is at the very foundation of our arts landscape in Chicago and beyond. The most suggestive individual piece of Calder’s work was 3D scanned and placed on the internet to further highlight this notion. As Chitty says, “A part of me is everywhere, in the classroom, at home, at the studio, and online.”

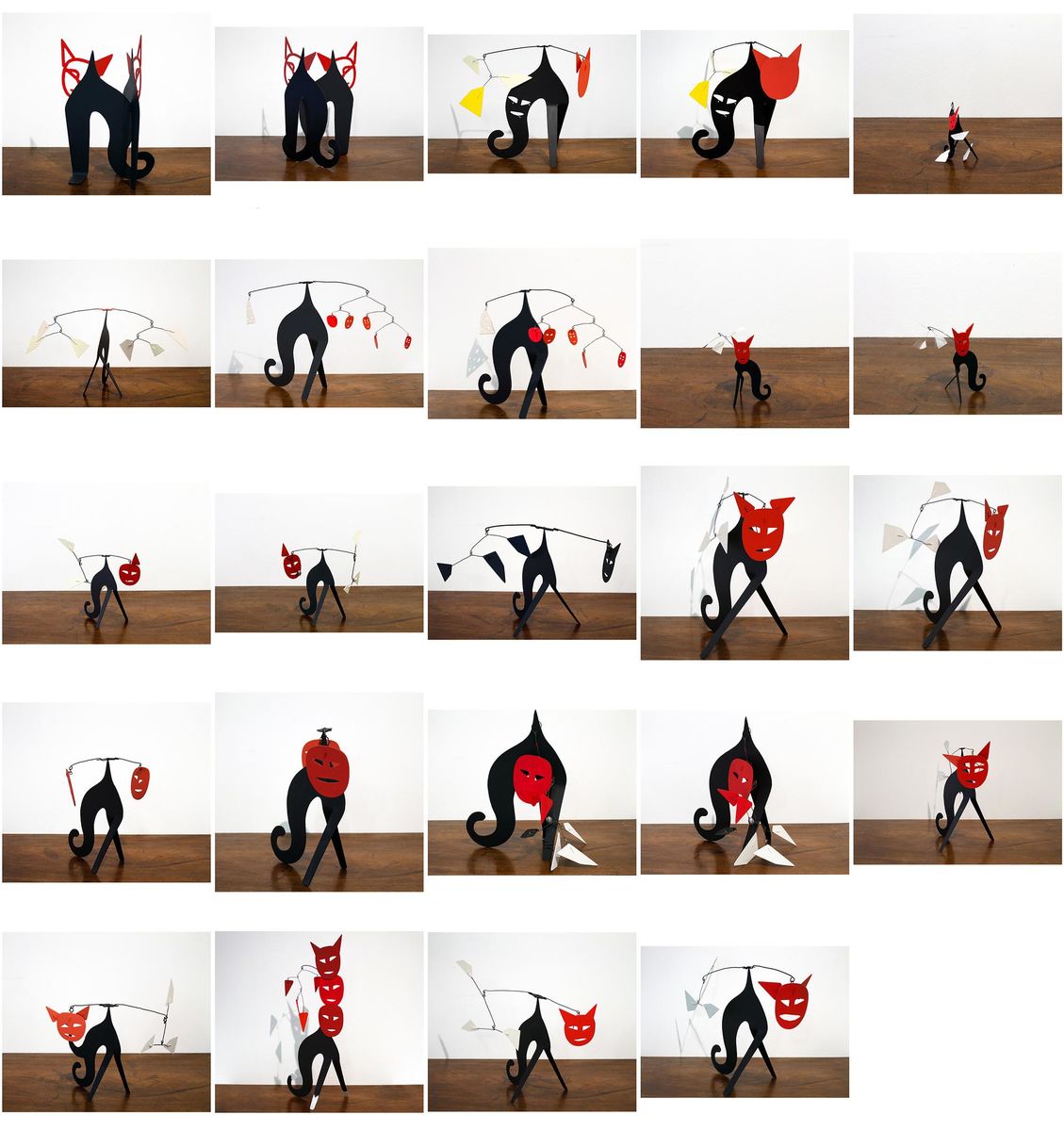

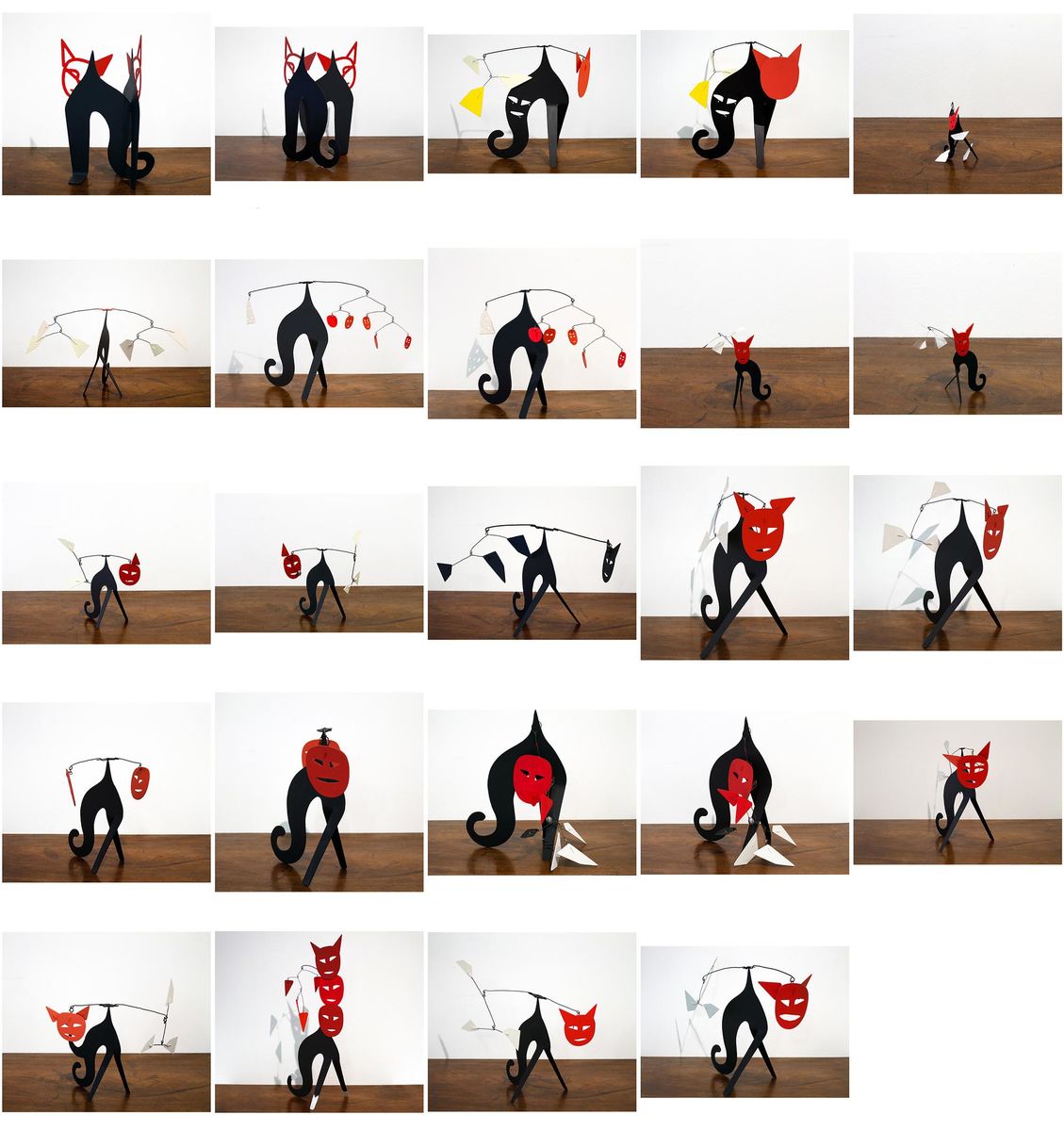

As a punctuating moment in the exhibition, Chitty prods the larger systems that guide museum programing, with her work A Bunch of Pussies (2020). As with the rest of the exhibition, Chitty considers how she can persuade the Calder works, and her audience, to move. Using a tongue-in-cheek double entendre in the title of her piece, Chitty observes that too often, inertia of any kind—political, social, or institutional—comes from a desire to mitigate risk and avoid possible failure. However as Chitty understands, change of any kind is impossible without risk. For this piece, Chitty reinterpreted Calder’s Chat-Mobile (1966), producing it over and over, based on photography of the artwork found online. Using the results from an image search as a blueprint for production, the result sometimes more closely followed the original design, and other times had a surreal effect. Throughout the run of the show, Chitty delivered more Pussies to the museum, each time the sculptures deviated more from the original work. Calder’s true work sat camouflaged in the gallery amongst the mounting Pussies scattered throughout the exhibition space.

Individual images of Alex Chitty’s Bunch of Pussies, 2019

Individual images of Alex Chitty’s Bunch of Pussies, 2019

Since Warhol’s Raid the Icebox, museums and institutions have made a practice of inviting guest curators, artists, and other outsiders to engage their collections, archives, and other holdings. Today,the form of the artist-curated museum exhibition is thriving, with some institutions making it a regular part of their programming. As was the case with Warhol’s exhibition at the RISD Museum, at the MCA Chitty subverted the standard practices of the institution while simultaneously uncovering them for museum visitors to see. This is perhaps the most compelling reason to invite artists and guest curators into museums: they can show us something new inside of a well-trodden form or collection. On the surface, for Chitty this meant elevating the behind-the-scenes practices of institutions. But looking more closely, she is also challenging the ultimate authority of the museum’s voice and dissecting the very systems—such as long-term loans—that simultaneously bring important historical artworks into public view and perpetuate the imbalance of representation in museum programming.

Institutional loans and contracts like the Horwich Family Loan are common across institutions in the United States, at varying scales. Notably, the Art Institute of Chicago recently received a major gift of forty-four artworks that stipulated the works be shown continuously for fifty years. This kind of philanthropy, while generous, has meaningful effects on museum programming as it foregrounds artists from the canon over lesser-known or more diverse voices, thereby limiting the amount of gallery space for exhibitions featuring new work or up-and-coming artists. This question of imbalance in museum programming is at the core of Chitty’s thinking as she reveals the larger systems that drive museum programs and seeks to empower her audience to challenge them. This approach calls to mind artist activist groups like the Guerrilla Girls, who have been exposing gender inequality in museum collections and exhibitions since the 1980s. Their mission has maintained its urgency and relevance, as more recent studies have shown that despite stated efforts to become more inclusive and diverse, many museums continue to lag in representation of women and people of color in their exhibition programs and collections.

Becoming the Breeze uses works by Alexander Calder to frame some of these issues. Through the conceptual conceit of movement, Chitty shows us not only how Calder’s mobiles themselves move, but how these works move as active agents within a network of unseen forces. As Chitty says, “I’m not showing you Calder, I’m using Calder to show you something else.” This “something else” includes the labor of museum staff, partnerships between private parties and public institutions, the emotional labor of friends and family, and of course, the air itself. The exhibition exists in a lineage of artist-curated museum projects while serving as a model for how museums—and other institutions—can work with artists to offer the viewing public a more holistic look into their practices. While this exhibition engages a particular set of objects within a specific institution, Chitty’s intention is that this type of inquisitive engagement will inspire audiences to similarly question, prod, and challenge the established systems in their own lives.

Alexander Calder’s (American, 1898–1976) mobile sculptures were made to move. In the 1930s photographer Herbert Matter (American, b. Switzerland, 1907–1984) captured Calder’s work in feverish, exaggerated motion. Using dramatic lighting and long exposures, Matter revealed the dynamic spirit of Calder’s artwork. With his camera he captured the mobiles’ motion over time as they created layered and interlaced trails of lights—a ghostly dance. But Matter was not the only artist to make Calder’s sculptures dance. Multiple experimental films were made, sets designed, and more recently, exhibitions curated to highlight the intended fluidity, motion, and spirit of Calder’s work.

The notion of movement was the genesis of the exhibition Becoming the Breeze: Alex Chitty with Alexander Calder at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (MCA). For artist Alex Chitty (American, b. 1979), the Calder sculptures and their potential movement became a salient metaphor for how one can inquisitively engage the social, political, and interpersonal forces in our lives—and, by extension, how one chooses to be in the world.

As visitors enter the MCA, one of the first things they encounter is an uncanny sight: what appears to be a frenetically spinning mobile by Alexander Calder. The mobile’s movement, almost frantic in comparison to its usual languid rotation, is driven by a motorized fan mounted on the adjacent wall. The work is, in fact, not one of Calder’s mobiles, but a replica of his Blue Among Yellow and Red (1963), made by Chitty. Titled Zeebo in they house (2019), Chitty’s stunt-double mobile greets visitors outside of the gallery space and introduces the framework for her exhibition and artistic intervention at the museum. With this work, Chitty validates the commonly held desire to see Calder’s mobiles move and importantly asks museum visitors to take a second look at what they are seeing.

Both Matter and Chitty brought their own creative vision to Calder’s artworks. It is this crossroads of artistic and curatorial practice—activating the works of one artist with the vision of another—that is the vital work of the artist curator. Becoming the Breeze is part of a rich history of artist-curated exhibitions and artist-led interventions into museum collections.

This history begins with Andy Warhol’s exhibition Raid the Icebox (1969–70), which is credited as the first artist-curated museum exhibition. At the time of the exhibition, the Rhode Island School of Design Museum (RISD Museum) had found itself in an unfortunate state of financial duress, and Warhol was invited to uplift the stagnating collection. In selecting objects for the exhibition, Warhol overlooked many of the museum’s better-known and cherished holdings, such as their costume collection and fine furniture by 18th-century Rhode Island craftspeople. He instead favored their lesser-known and peculiar holdings, such as their collection of shoes and umbrellas. In all, Warhol selected roughly 400 objects from the museum’s collection, ranging from paintings to Native American pottery to wallpaper. By presenting the lauded objects from the collection alongside those considered to be average or unremarkable, Warhol challenged the notion that any single object in the collection had greater value or importance than another. Writing on the exhibition, curator Anthony Huberman notes that Warhol “recognized that there is no such thing as an ‘ideal’ or even ‘good’ or ‘bad’ collection, collector, or collecting institution,” and that the artist’s intention was to “flatten and nullify the playing field so as to render bankrupt the very notion of winners and losers.

The manner in which Warhol exhibited the collection further reinforced this subversion of museological and curatorial convention. Rather than following standard museum display methods, Warhol insisted that the works be shown in the galleries just as they existed in storage: in stacks against the walls, on cluttered shelves and racks, and in cellar-like dim light. The project aligned with Warhol’s broader artistic ethos, which disrupted hierarchical distinction between high and low culture by championing the ordinary, the overlooked, and the everyday. Warhol’s seemingly cavalier display strategy was unsettling at the time, in particular to the museum directors, as it not only challenged the authority of the museum curator, but it also very clearly revealed the lack of funding and organization befalling the museum’s collection, as evidenced by their disorderly storage practices and facilities.

In Becoming the Breeze, Chitty similarly chose to display several of Calder’s works as she had encountered them in storage during her research visits to the MCA. Calder’s bronze sculpture A Detached Person, for example, is shown disassembled, as it would be stored, as is his mobile Black: 17 Dots (1959), which is shown tied into its custom storage tray. Furthermore, Chitty’s sculptural structure Alex (linked), on which several works by Calder are displayed (including Orange Under Table [c. 1949], Performing Seal [1950], Black: 17 Dots, A Detached Person [1944/1968], and Chat-Mobile [1966]), was made using repurposed metal shelving units that reference what is used in the MCA’s storage facilities. Like Warhol, Chitty was moved by what happens backstage and wanted to share with the public what is not normally seen in the museum galleries. In Warhol’s case, this dignified ordinary and forgotten objects in the collection; for Chitty, it elevated the careful work of museum employees to assert that their care of the artwork is as important as the artwork itself.

This consideration for the work of museum employees is also revealed through Chitty’s photographic diptych Precedence (2019). Two photographs depict the installation process of Calder’s mobile The Ghost (maquette) (1964), in which three of the museum’s preparators are shown gently raising the sculpture out of its storage tray for installation in the same atrium. These three technicians are only a fraction of the behind-the-scenes staff at the museum working to produce exhibitions. Chitty’s photographs elevate them and the work that they do—work that, when done well, is meant to be invisible. The Ghost (maquette) was installed on a hook and wire in the ceiling, which Chitty asked to be left behind as part of the exhibition. The hardware hangs from the ceiling, spot lit and titled The Ghost (Louisa) as a nod to Calder’s wife, Louisa, and all of the invisible partners and collaborators that work to support the creative process.

Beyond revealing the many unseen institutional processes required to produce a museum exhibition, Chitty also reveals how artworks are made—how they come to be in the world. Chitty’s practice is most recognizable by her expert craftwork and her unwavering invitation to look (and to spend time looking) at her peculiar compositions and materials. For the sculpture of Alex (linked), however, Chitty opted for a different, less polished approach. She left exposed the raw welded corners of the repurposed shelving units, as well as measurements written in black marker on the surface of the work. Just as she revealed the inner workings of the museum, Chitty left behind these subtle gestures, like breadcrumbs intended to lead viewers through her artistic process. As with the crop-marks made visible on the aforementioned photographic diptychs, Chitty included other clues: the sharpened nub of a #2 pencil, jammed in place as if to level a piece of shelving, a portion of a wooden log that holds up part of the structure displaying Calder’s Black: 17 Dots. With these moves, Chitty goads the viewer, encouraging them to ask questions about whether these traces are intentional or left behind in haste. As an artist whose practice toggles between object making and image making, Chitty applied her own studio logic to Calder’s historical works, each time pushing the viewer to question what they are seeing.

While Warhol’s approach sought to engage the RISD Museum’s collections in surprising new ways,other artist-driven exhibitions have taken a more intimate approach: enlisting artists to engage the work of another singular artist. One recent example is Specific Objects Without Specific Form (2016). For the traveling show, organizing curator Elena Filipovic invited three contemporary artists—Carol Bove (Swiss, b. 1971), Danh VÅ (Danish, b. 1975), and Tino Sehgal (German, b. 1976)—to co-curate exhibitions of works by Felix Gonzalez-Torres (American, b. Cuba, 1957–1996) at three different venues. Gonzalez-Torres’s conceptual artworks often exist as sets of instructions or parameters for installation that are described in an accompanying certificate of authenticity. The works are not discrete objects kept in storage, but rather are manifested anew each time they are exhibited. As an example, the certificate for Gonzalez-Torres’s “Untitled” (Portrait of Dad) (1991) specifies that the work consist of 175 pounds of white candies individually wrapped in cellophane; however, the particular shape that the mass should take is not specified. The artist originally displayed this work piled in the corner of a room; consequently, this shape and placement has become the implied museum standard. Gonzalez-Torres’s lack of specification for the shape was deliberate, as he intended for this aspect of the work to be open to interpretation. At each of its three venues, Specific Objects Without Specific Form operated like a game of round robin. First, Filipovic installed Gonzalez-Torres’s work, then, halfway through the exhibition’s run, one of her artist co-curators would reinstall the exhibition, often altering the manifestation of Gonzalez-Torres’s artworks in the process. In the iteration at Fondation Beyeler, Filipovic initially installed “Untitled” (Portrait of Dad) in a rectangle on the floor; later Carol Bove re-interpreted the work by simply turning that rectangular pile ninety degrees. The same work at the Museum für Moderne Kunst was installed two different ways by Tino Sehgal: first as a pile in a corner and later along the edge of a wall. By challenging traditional institutional exhibition formats, Filipovic, Bove, VÅ, and Sehgal foregrounded the underemphasized malleable nature of Gonzalez Torres’s work.

Working in a mode similar to Fillipovic and her artist co-curators, Chitty also explored the ambiguities of a document that governs the display of Calder’s artworks at the MCA: the Horwich Family Loan. While most of the Calder artworks in the exhibition are not part of the MCA Collection, they are nonetheless an important part of the museum’s history, having been cared for and exhibited at the museum for 25 years. In 1995, founding MCA members Ruth and Leonard Horwich initiated a long-term loan of fifteen artworks by Alexander Calder to the museum. Since then, a portion of the artworks from the original loan have been gifted by the family, becoming part of the museum’s permanent collection. The remaining works in the loan are subject to its terms that mandate that, so long as they are under the care of the museum, they must be on view most of the time. In Becoming the Breeze, Chitty considered this directive in numerous ways— her project questions the terms of the loan and whether it can be satisfied if the artworks are shown as photographs, facsimiles, or in silhouette as with Calder’s Performing Seal (1950).

In this exhibition, Chitty carefully considered the history and provenance of each artwork, sometimes incorporating this history in its display. In her presentation of Calder’s Orange Under Table (c. 1949), Chitty nodded to the peripatetic nature of artworks by linking the work to its owners, the Horwich Family. The glass table on which the sculpture is displayed is a near-copy of the table in the Horwich’s dining room, where the sculpture lived before moving to the museum. Photographs of the Horwich’s home reveal how they cohabitated with the artworks in their collection, Orange Under Table held a prominent place, sitting at the head of their dining table as if it were a stand-in for the host. Chitty acknowledged this important history of the artwork’s provenance and installation in the lender’s home in her reinterpretation. In this way, she not only recalled the movement of Calder’s work through time and space, but also emphasized the partnerships between private parties and public institutions that are at the foundation of many museums.

Work shown: Alexander Calder, Orange Under Table, c. 1949. Sheet metal, paint, metal rods, and steel wire; 72” × 82” diameter (182.9 × 208.3 cm diameter).The Leonard and Ruth Horwich Family Loan, EL1995.11

Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago, © 2019 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

As Becoming the Breeze continues in the lineage ofartist-curated exhibitions, several other museums in the United States have concurrently invited artists to intervene in their collections. Of particular relation and resonance to the MCA’s exhibition is Brendan Fernandes: Contract and Release. In this exhibition, Brendan Fernandes (Canadian, b. Kenya 1979) augmented Noguchi: Body-Space Devices, an exhibition at the Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum in New York. Body-Space Devices includes selected works from the permanent collection that demonstrate sculptor Isamu Noguchi’s (American, 1904–1988) interest in engaging the body.

Noguchi’s work in sculpture and design was deeply tied to movement and the relationship between viewers, objects, and space. His sensitivity to the human body in his work is pushedfurther by Fernandes’s engagement with it. Stage props Noguchi created for Martha Graham’s (American, 1894–1991) dance performances sit prominently within the exhibition; a rocking chair Noguchi made for the 1944 production of Appalachian Spring was of particular interest to Fernandes, a multi-disciplinary artist and trained dancer. Fernandes took the conceit of Body-Space Devices and augmented it with his own artworks, as well as with weekly dance choreographies. He reinterpreted Noguchi’s 1944 rocking chair and designed six alternative versions to serve as training tools and props for the dancers in his performances.

Like Chitty, Fernandes worked with the particular constraints of an institution and its objects. As withCalder’s mobiles, which viewers are prohibited from activating, Noguchi’s sculptures in the museum are not to be touched. For Contract and Release, Fernandes’s dancers climb and slide along the curves of Noguchi’s Play Sculpture (c. 1965), a large-scale red sculpture inside the exhibition intended for outdoor display. In another gallery of the museum, the dancers carefully disassemble and move wooden copies of Noguchi’s bronzes made by the museum’s production team. But these copies were not originally intended for public display: the wooden maquettes were made as an internal teaching tool for the museum’s preparators to practice the gentle assembly of Noguchi’s works. Here Fernandes brings the behind-the-scenes work to the fore. Similar to how Chitty revealed the complexities of Calder’s artworks with her display of A Detached Person, or the photographic diptych Precedence, Fernandes offered museum visitors an understanding of the interlocking, puzzle-like construction of Noguchi’s bronzes with his interventions.

Where Fernandes used the framework of dance to activate Noguchi’s work, Chitty used sculptural interventions to do the same with Calder’s work. This strategy is most evident in Chitty’s re-presentation of Calder’s A Detached Person. A Detached Person (1944/1968) consists of five distinct bronze pieces that stack and balance on one another to form a seated figure. Materially, this series represents an anomaly in Calder’s career, and yet it reveals his process in ways that other works of his do not. The range in date marks the continuum of this practice: 1944 is when the plaster or clay body was made, and 1968 when he was able to cast the works in bronze. Then, as told by the artist himself in his biography, the decision to abandon this

material as it had been considered by his gallery a commercial failure. The artist’s practice, economic concerns, and pressure to perform within the market are all embodied within this one work. For this reason the sculpture, as well its title, served as a fitting conveyance for Chitty to reflect on what it means to be an artist working today.

In the MCA exhibition, A Detached Person is presented on a display shelf made of industrial shelving and a retired shipping crate. Each constituent bronze piece sits or balances on a different level of the display structure—inspired by the work of mid-century designer Charlotte Perriand (French, 1903–1999)—in ways that indicate the balanced construction of Calder’s sculpture. Here Chitty’s audience has to visually reconstruct the piece, understand its stacking components, and look intently to understand the work as a whole. But beyond pushing her audience to do the work of mentally assembling the piece, the purposefully scattered bronze pieces are meant to reflect the imbalance of labor in the arts today. In a competitive, saturated, and infamously undercompensated industry, artists, curators, administrators, preparators, critics, writers, and educators lead a multihyphenate existence as a means for survival—each one moonlighting in different parts of the industry to produce the rich culture that is at the very foundation of our arts landscape in Chicago and beyond. The most suggestive individual piece of Calder’s work was 3D scanned and placed on the internet to further highlight this notion. As Chitty says, “A part of me is everywhere, in the classroom, at home, at the studio, and online.”

As a punctuating moment in the exhibition, Chitty prods the larger systems that guide museum programing, with her work A Bunch of Pussies (2020). As with the rest of the exhibition, Chitty considers how she can persuade the Calder works, and her audience, to move. Using a tongue-in-cheek double entendre in the title of her piece, Chitty observes that too often, inertia of any kind—political, social, or institutional—comes from a desire to mitigate risk and avoid possible failure. However as Chitty understands, change of any kind is impossible without risk. For this piece, Chitty reinterpreted Calder’s Chat-Mobile (1966), producing it over and over, based on photography of the artwork found online. Using the results from an image search as a blueprint for production, the result sometimes more closely followed the original design, and other times had a surreal effect. Throughout the run of the show, Chitty delivered more Pussies to the museum, each time the sculptures deviated more from the original work. Calder’s true work sat camouflaged in the gallery amongst the mounting Pussies scattered throughout the exhibition space.

Since Warhol’s Raid the Icebox, museums and institutions have made a practice of inviting guest curators, artists, and other outsiders to engage their collections, archives, and other holdings. Today,the form of the artist-curated museum exhibition is thriving, with some institutions making it a regular part of their programming. As was the case with Warhol’s exhibition at the RISD Museum, at the MCA Chitty subverted the standard practices of the institution while simultaneously uncovering them for museum visitors to see. This is perhaps the most compelling reason to invite artists and guest curators into museums: they can show us something new inside of a well-trodden form or collection. On the surface, for Chitty this meant elevating the behind-the-scenes practices of institutions. But looking more closely, she is also challenging the ultimate authority of the museum’s voice and dissecting the very systems—such as long-term loans—that simultaneously bring important historical artworks into public view and perpetuate the imbalance of representation in museum programming.

Institutional loans and contracts like the Horwich Family Loan are common across institutions in the United States, at varying scales. Notably, the Art Institute of Chicago recently received a major gift of forty-four artworks that stipulated the works be shown continuously for fifty years. This kind of philanthropy, while generous, has meaningful effects on museum programming as it foregrounds artists from the canon over lesser-known or more diverse voices, thereby limiting the amount of gallery space for exhibitions featuring new work or up-and-coming artists. This question of imbalance in museum programming is at the core of Chitty’s thinking as she reveals the larger systems that drive museum programs and seeks to empower her audience to challenge them. This approach calls to mind artist activist groups like the Guerrilla Girls, who have been exposing gender inequality in museum collections and exhibitions since the 1980s. Their mission has maintained its urgency and relevance, as more recent studies have shown that despite stated efforts to become more inclusive and diverse, many museums continue to lag in representation of women and people of color in their exhibition programs and collections.

Becoming the Breeze uses works by Alexander Calder to frame some of these issues. Through the conceptual conceit of movement, Chitty shows us not only how Calder’s mobiles themselves move, but how these works move as active agents within a network of unseen forces. As Chitty says, “I’m not showing you Calder, I’m using Calder to show you something else.” This “something else” includes the labor of museum staff, partnerships between private parties and public institutions, the emotional labor of friends and family, and of course, the air itself. The exhibition exists in a lineage of artist-curated museum projects while serving as a model for how museums—and other institutions—can work with artists to offer the viewing public a more holistic look into their practices. While this exhibition engages a particular set of objects within a specific institution, Chitty’s intention is that this type of inquisitive engagement will inspire audiences to similarly question, prod, and challenge the established systems in their own lives.