A Complex History: Nate Young and Mika Horibuchi Bring Their Labor to the Forefront at Driehaus Museum Exhibition

Newcity Art / Nov 2, 2020 / by Jenn Stanley / Go to Original

The Richard H. Driehaus Museum invites art and architecture lovers to shift their warped and worn perception of time with the second iteration of its “Tale of Today” contemporary art initiative. Through the end of January, visitors to the Gilded Age mansion and museum can check out the exhibition, featuring two contemporary Chicago-based artists—Nate Young and Mika Horibuchi—who’ve created site-specific works responding to the complex history of the building.

“When we asked ourselves how a young museum housed in a Gilded Age mansion could offer a way to connect past and present, we found the answer in the legacy of the Nickerson family, through their intentions, and the art and design embedded on the walls of their 1883 home,” said Anna Musci, the museum’s interim executive director, during a live-streamed event for the show’s opening. The Nickersons rose to prominence with the national banking industry, at one point owning more stock than anyone in the United States. The family spared no expense on the aesthetics of their three-story Near North Side mansion, which was designed by Edward J. Burling of Burling and Whitehouse.

The exhibition is part of the museum’s contemporary art initiative to add context to the space to bring out “both the glorious and the difficult narratives tethered to this era,” according to a press statement.

During the September 26 opening, the artists joined curator Kekeli Sumah, Jane Addams Hull House curatorial manager Ross Jordan and Ann Lui, assistant professor of practice in architecture at the University of Michigan and founding principal of Future Firm, in a panel discussion to discuss the work as well as the house’s legacy.

“A house that’s preserved feels like it has one narrative that’s presented, but in both [Young and Horibuchi’s] works it seems there’s space to call out narratives that aren’t part of the primary history,” Lui said. “That started to make me think, ‘This wood that’s on the wall, where’s that wood coming from?’”

Horibuchi says both she and Young relish in the labor of craft-making. “We both work with traditional materials that haven’t changed much over time, and I think that’s a nice thread throughout the two separate exhibitions.”

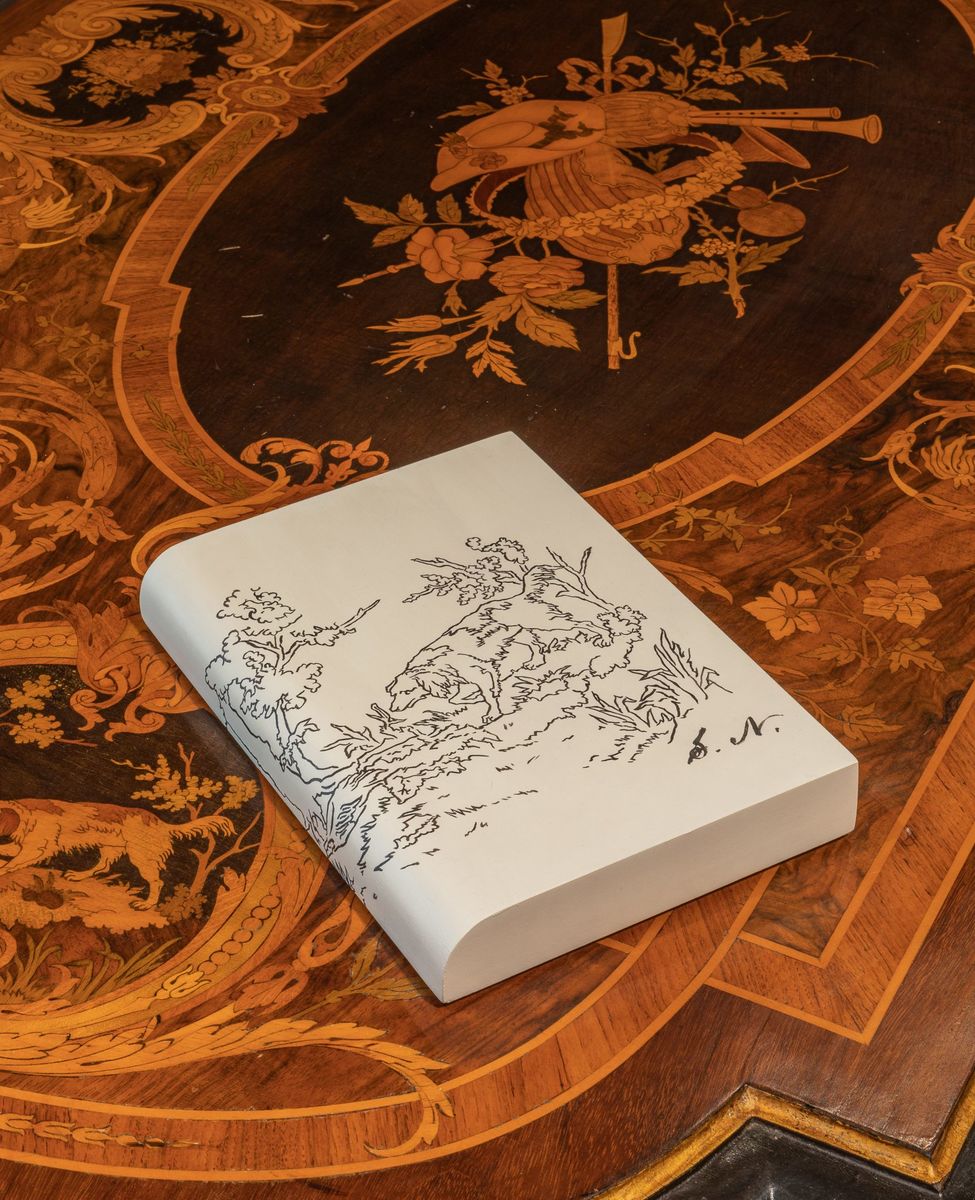

Horibuchi uses mimicry and playful deception to question existing historical narratives. She says her work poses questions about representation, ownership and authorship, particularly within the context of museum didactics. In one series, she uses trompe l’oeil to simulate photographs of objects from the Nickerson’s collection of artifacts from Japan and China, accompanied by grayed-out blocks where text would be.

“I wanted to approach the works for this exhibition examining the two main characteristics of this space which are one, a house, and another, a museum,” Horibuchi says.

She highlights the more residential aspects of the space in Samuel Nickerson’s former bedroom, where she uses oil on linen and panel to create the effect that her paintings are objects that have been in the room for decades. A painted portrait of Mr. Nickerson that mimics the style of a portrait of Lucius George Fisher (the mansion’s second owner) by Ralph Clarkson in the Smoking Room on the first floor, for example, is placed alongside the mansion’s original artifacts, leaving it up to the viewer to decide what’s authentic.

“I wanted to create the space for a new author to create a new historical piece of fiction,” Horibuchi says. But unlike the people who built the mansion one-hundred years ago, the artists aren’t distanced from their labor, something both artists explore.

“Often the laborer doesn’t have the agency,” Young says. “They’re hired to produce the thing for the other person who, because of their economic and social status, has the agency.”

A multidisciplinary artist who often employs crafts like furniture-making in his installations, Young was immediately drawn to the mansion’s exquisite woodwork. He wanted to create pieces that could stand on their own in the space while feeling like they belonged there, highlighting the craftsmanship most of all.

His intricate cabinets hide ghostly objects that don’t quite belong. Holograms of horse bones that disappear as visitors approach evoke Young’s previous work, and are part of an ongoing project exploring his great-grandfather’s journey from North Carolina to Chicago at the beginning of the Great Migration.

“Our presence makes them more difficult to see,” Young says. “Our own being, as we approach it, as we go through life, it’s not that we become fully aware of who we are. We maybe become less aware because by the time we find out who we are we’ve already changed.”

Curator Kekeli Sumah believes that Young and Horibuchi’s installations provide much needed contemporary perspectives to the well-preserved historic space, challenging narratives that have been taken for granted and shining a light on those that have been overlooked. “To make conversations about the Gilded Age relevant to today’s society, it is important to have contemporary emerging voices from the city join the conversation.” (Jenn Stanley)