Artist Carmen Winant on Why 2,000 Images of Childbirth Belong at MoMA

Vogue / Mar 19, 2018 / by Laura Regensdorf / Go to Original

Carmen Winant in her Columbus, Ohio, studio with her sons, Carlo, 2, and Rafa, 2 months.Photo: Luke Stettner

In the final spread of Carmen Winant’s new book,My Birth—a moving interplay of collected photographs and personal writings on the confounding process of labor—a black-and-white image shows a new mother gazing into a hand mirror. On the opposite page Winant offers her own reflection: “By the time you are reading this, cracked open and flimsy, I will have birthed again. I am no closer to understanding who takes possession of this process, or locating the words to make it known.”

The first part is true: Winant delivered her second son two months ago. But the rest? After a yearlong dive into the subject—combing for vintage pamphlets, sourcing materials from “OG midwives,” and reading Margaret Atwood, Sylvia Plath, Adrienne Rich, and so many others—the artist seems to have come as close to grasping the unknowable as one can get, thanks to twin projects that have debuted this week. If the book skews intimate (snapshots of her mother’s own home deliveries weave in a rare thread of autobiography), Winant’s debut installation at the Museum of Modern Art is monumental. Part of “Being: New Photography 2018,” the collage, also titled My Birth, takes over two facing walls in a narrow 20-foot-long gallery. There, Winant has taped up more than 2,000 found images of women careening through the full, uncensored continuum of birth.

Carmen Winant’s My Birth (detail), 2018. Site-specific installation of found images, tape. The Museum of Modern Art.Photo: Kurt Heumiller / © 2018 Carmen Winant

“I’ve never been inside of a project in quite the same way,” Winant says by phone from Ohio, where she is an assistant professor at the Columbus College of Art & Design, referring to the way that real-life experience blurred with the flood of images taking over her studio: women weeping into pillows, collapsing into partners’ arms, submitting to medical devices (bane or blessing of modernity?), and bringing bodies out of their bodies.

Putting childbirth—at once universal and frankly mind-blowing (witness what a placenta looks like)—on display is a bold move for MoMA. So is including found imagery in a group exhibition otherwise showcasing those who wield cameras, a sign of Lucy Gallun’s “daring as a curator,” says Winant. It’s also a marker of cultural change for an artist whose grandmothers remember nothing of their births, owing to a potent, then routinely administered sedative nicknamed “twilight sleep,” which “sounded like just the sort of drug a man would invent,” as Plath wrote in The Bell Jar. Here, Winant talks about the power of images in seminal books like Our Bodies, Ourselves(1971), her own self-described “possession” during childbirth, and the duty of raising sons in the age of Trump.

Your work often explores facets of women’s bodies. What led you to this subject?

Just a couple weeks after I gave birth [the first time], I remember reading an interview with the artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles, and she was talking about how in 1968 after she gave birth, she was shocked that no one asked about it. She said something like, “Weren’t they curious about what it felt like to create life? But with no language, it was like I was mute.” And I wept when I read those words because I was undergoing a similar experience, having never recognized it for myself. I felt more than eager to talk about the experience; I felt like it was necessary. And for whatever reason—because people wanted to respect my privacy or because they didn’t know how to talk it—it felt like this immensely cloistered experience. I didn’t want it to be, nor do I feel like it should be. [Ukeles] says over and over, “There was no language; no one asked me questions.” And I actually come up with a series of questions in the book to act as propositions that could be put toward a woman who has given birth, everything from the practical to the metaphysical. [Ukeles] put forth this notion that birth is invisible in culture and that we don’t have a language to describe it. I was curious as to what that language could look like, visual or pictorial.

When MoMA approached you, did you already have the idea for My Birth in mind?

”¨It had already been sort of germinating. I remember having the feeling, Can I do this? Can I put 2,000 images of women giving birth in the Museum of Modern Art? That felt, to me, like a kind of risky proposition. It’s startling material and potentially sensational to some people, and at the same time, it’s really vital and important.

Vitalis exactly the word. Could there be any work more vital than a work about the start of life? But it’s true, some people will have a hard time with this.”¨

Even I, and I am someone who has given birth twice and am profoundly feminist and this is my life’s work, still don’t think it’s easy material. I just spent four days installing it, and it was exhausting and trying in its own way to see these images over and over. Of course, there’s something beautiful and revelatory about it, but that’s not all that it is; it’s a moment of profound physical strain and sometimes agony. The work is just as much about that as it is about the tenderness, the surreality. I’m also interested in how these photographs can act—or I should say, did act—as sort of agents themselves of political change,Our Bodies, Ourselves being the most famous example. That was a book created by women for women to disseminate information about their bodies that they didn’t otherwise have access to. Here is what an abortion looks like, here are the tools used in abortion, here is how to masturbate, here is what it looks like to give birth. There’s something concrete about how the politics flows through the work. And it’s complicated: It was really, really hard to find nonwhite women for this installation, which in some ways ended up being part of the work, whose bodies are absented and whose bodies are made present.

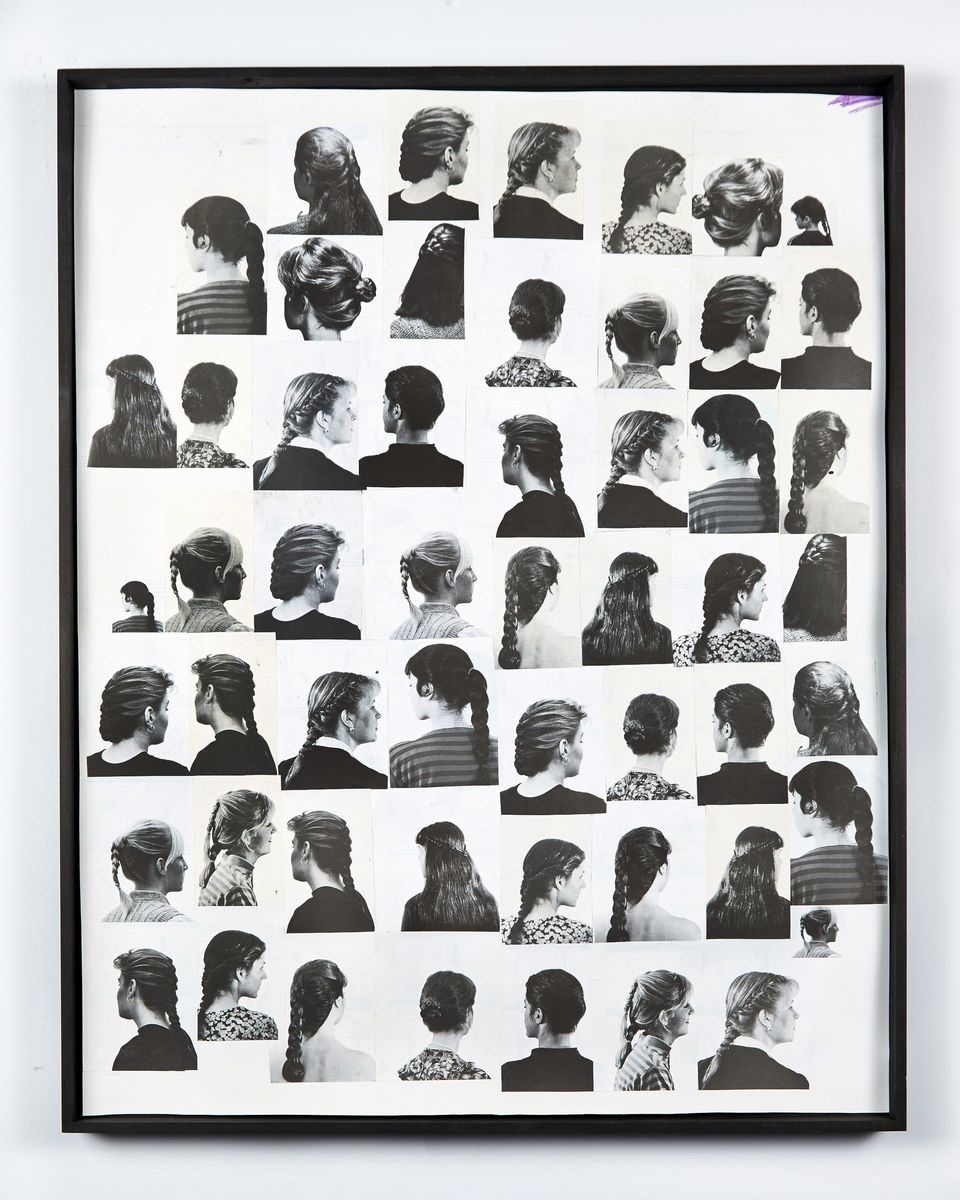

White Women Look Away, 2016. Found images, artist frame, colored pencil.Photo: Courtesy of Fortnight Institute

Your mother appears in the book alongside other women in these uncannily similar postures. It really reinforces how universal the birth process is.Ӭ

Totally. When you’re undergoing this experience, like so many intense physical sorts of experiences in one’s life, it just feels so singular, like you’re the only person who’s ever gone through it—which is, of course, so ridiculous, to apply that logic to birth. There is something kind of tender about that action of pairing my mother’s gestures with these other unidentified women who are equally lost inside of their bodies and the overwhelmingness of it. I did not [incorporate her into the installation, though]. I’m interested in how images of strangers can act as a sort of a surrogate for me and for my body and my experience.

The language of birth, like surrogate, is inescapable.ӬI

know! [laughs] I was installing at MoMA, and there was so much accidental innuendo. You’re talking about discharging and pushing something out and seeing something to completion and bearing something. It’s almost ridiculous. And what’s unique about the install is it’s in a really small gallery that connects the two larger ones, so you have to pass through the space that my work is in in order to move through—again, innuendo—to the other side. For this installation I’ve used just blue painter’s tape to adhere all the images, which, for me at least, is an important detail because it’s not some fancy super-archival acid-free tape or something. It’s the tape that I use every day, so it kind of references the labor of the studio.

Installation view of Carmen Winant’s My Birth, 2018, installed as part of “Being: New Photography 2018” at The Museum of Modern Art.Photo: Kurt Heumiller / © 2018 The Museum of Modern Art

You also have a work on view at theSculptureCenter, with images of self-defense. How do you see that exhibition and My Birth sitting in terms of national conversations?

I started that piece, which is called Looking Forward to Being Attacked, far before whatever we call our current #MeToo movement erupted, and it was really interesting to continue making it and put it into the world in the midst of this cultural conversation because it does shift, I think, the way people react to the work, in some ways for better and for worse. To me, the works are inexorably linked to each other. The notion of self-defense and giving birth are, of course, different kinds of experiences, but both of them, at least in my mind, are political; both of them are about protecting women’s bodies and [imbuing] them with a kind of power. All of the images from Looking Forward to Being Attacked, which is a title of a book from which some of the images come, are all these instructional images that basically tell women how to save their own lives. And in a way, that’s not so dissimilar fromOur Bodies, Ourselves saying to women: “If you get a botched abortion, here’s what you do. Look at these images.”

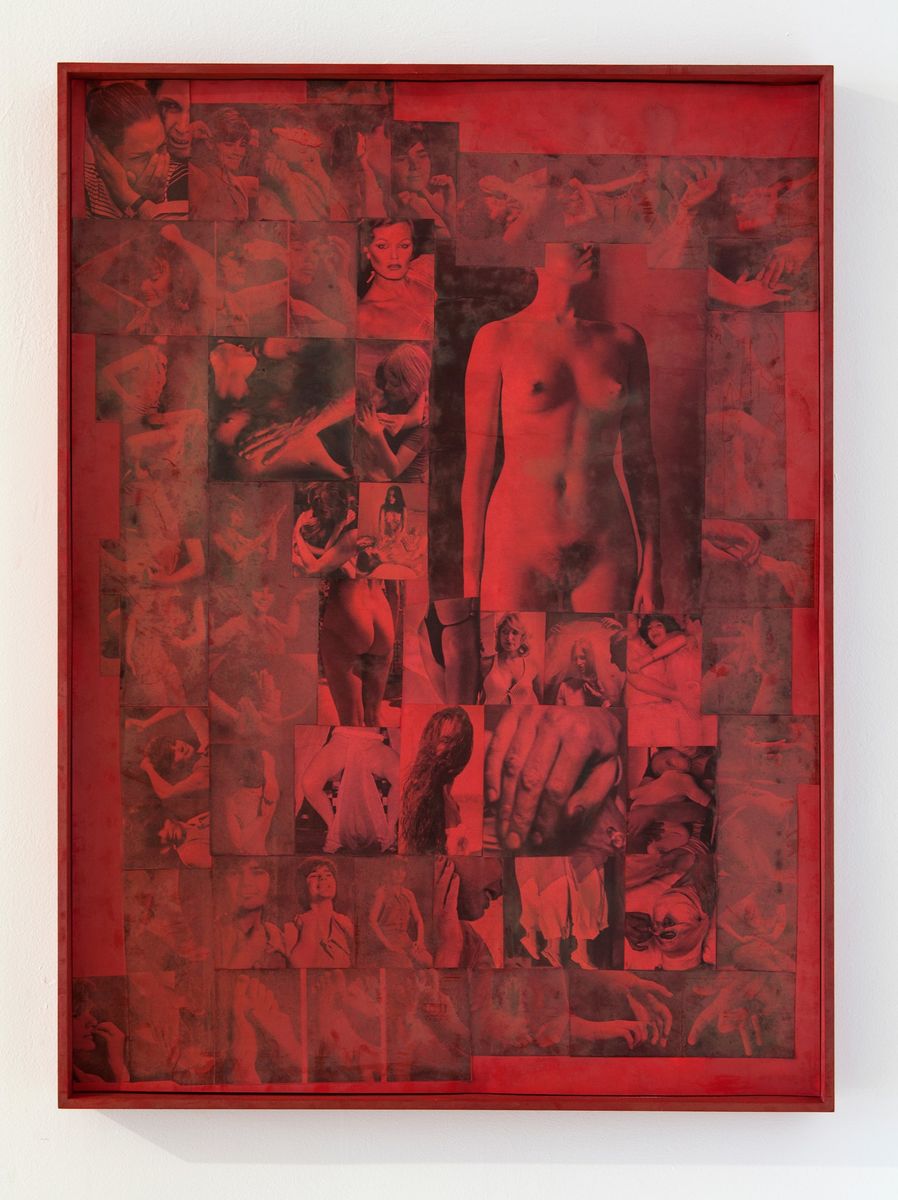

Hur, 2016. Found images, food coloring, artist frame.Photo: Courtesy of Fortnight Institute

In the book you write, “I want to beg: Just ask me.”So how was your first birth? You mention the “possession”—that you couldn’t open your eyes. What a description.

Yes, it was a very strange thing, I have to say. I think it was just from exhaustion. My first birth was over 30 hours, but I used to be a long-distance competitive runner, so I’m used to endurance, you know? I’m used to sustaining and managing pain over a long period, so I didn’t anticipate some of the physical reactions that would occur, like that one. For hours I really couldn’t open my eyes; I could just sort of flutter them open. So, yeah, that was not an exaggeration. Also, the notion of possession is that there’s another spirit actually physically inside of you, so I like the idea that then that person leaves you and then you’re no longer possessed.

What about the second birth? Your list of questions for new mothers includes “Has there ever been so much unknown?” and “Has there ever been so much known?” I imagine there’s much more known?

For sure. I went into my first birth with no bodily intelligence to anticipate what the experience would be. In that sense, the second birth was totally distinct. But also I had been spending nine months culling images and looking at pictures of women’s births, which led me, like, to Adrienne Rich and Of Woman Born, so I was really knee-deep in the material. I approached this birth really differently and had my husband [the artist Luke Stettner] take many, many photographs. I was sort of interested to experience it as—God, this is going to sound kind of obnoxious—almost an art project, do you know what I mean? Because I wasn’t fearful in the same way I was, to be honest, with the first birth. I was interested in collecting information and owning the experience in a way I wouldn’t have been able to the first time. But I don’t know how to answer that question.

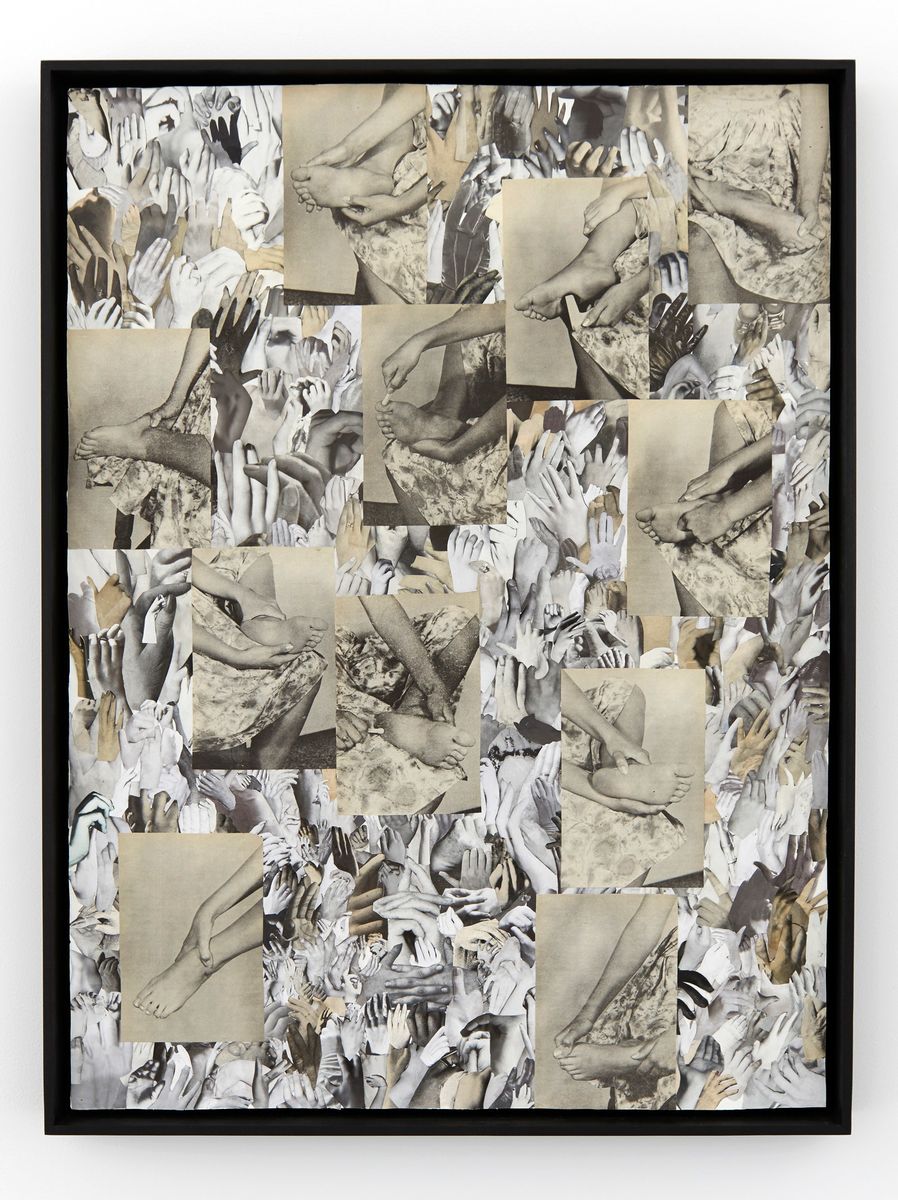

Looking Forward to Being Attacked, 2016. Found images, artist frame.Photo: Courtesy of Stene Projects

What are your two sons’ names?”¨

Rafa is my younger son; Carlo is my older son. So I have two boys in the midst of such a women-focused investigation.

But, like the cover story in last week’sNew York magazine, there’s so much informed talk now about how to raise boys.

”¨Totally. It’s such an interesting question now in the age of Trump. I think people actually are so much more sensitive to what it means to raise a son and how to do that in a feminist fashion. I don’t exactly know myself.

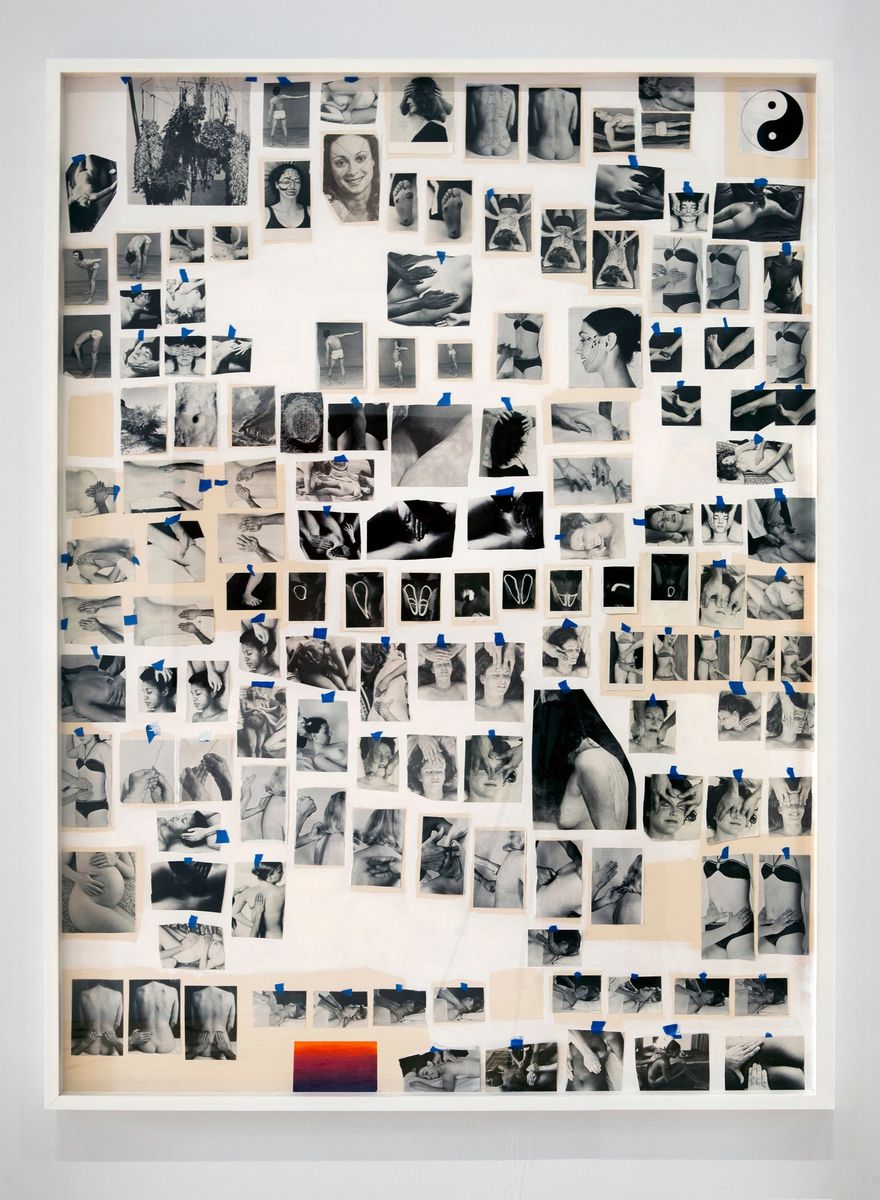

Self Healing, 2016. Found images, acrylic paint, matboard, painter’s tape, colored pencil.Photo: Courtesy of Fortnight Institute

Given that your work deals with subjects that are often underrepresented, did you ever go through a phase where you wondered if it was “important” enough?”¨

Yeah. Often, probably more out of judgment, I find myself thinking, Is this serious work? Will people take this seriously? I think that it’s my own inculcated sexism. The idea that work that is about women’s bodies and lives and experiences isn’t somehow critical or valid in the same way is something that I’ve really had to wrestle with—and I’m not someone who is on the fence about my feminism! I still work through it. It’s hard as a woman to undo your own conditioning, no matter how radical or progressive you are.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.