Sharón Zoldan Shares her Art Basel in Miami Beach Finds

Whitewall / Dec 6, 2021 / by Sharón Zoldan / Go to Original

Samira Yamin, “All the Skies Over Syria,” 2018-202, 58 x 87 inches, photo by Evan Jenkins, courtesy of the artist and PATRON Gallery, Chicago.

All the Skies Over Syria by Los Angeles artist Samira Yamin shown at is an incredibly subtle work, but without a doubt her pièce de résistance. Over the course of several years, Yamin mined TIME magazines from 2011 onward, isolating images featuring skies over Syria. She then excised small geometric shapes to create an elaborate mosaic based on ancient patterns of Islamic Sacred Geometry, a belief system that assigns order to chaos. The mosaic-like effect of the work ripples out in concentric circles, a marker of time like the rings of wood of a cut tree trunk.

Through the lens of the “War on Terror” and the American bias against the Middle East, the sky is always pictured overcast, gray, smoky, fiery—never blue. However, since TIME magazine is printed on flimsy paper meant to be discarded, over time, as the work continues to be shown in exhibitions, gallery shows, and art fairs, the thin, non-archival material will eventually fade to cyan, a greenish-blue. The artist’s hope is that the work joins the collection of an institution that has in-house conservators, like The Getty or LACMA.

Naama Tsabar, “Work on Felt (Variation 29) Purple,” 2021, carbon fiber,”‹ ”‹epoxy, wood, felt, microphone, guitar amplifier, 80 3/4 x 66 1/2 x 21 3/4 inches, courtesy of the artist and Shulamit Nazarian, Los Angeles.

Naama Tsabar’s work was pervasive throughout this art fair week. At The Bass she held several performances and her work was on view at the booths of Paul Kasmin, Goodman Gallery, and a solo presentation at —which was a great way to dig into the artist’s body of work as a whole. I particularly love her works on felt, part of her series of industrial felt sculptures outfitted with guitar or piano strings that can be played and strummed like a musical instrument. These pieces draw on her previous experience playing in an electro-punk band, not to mention their relation to one of my favorite artists, Robert Morris, and his use of industrial felt to relate to the body and his collaboration with the New York dance scene.

Diedrick Brackens, “once more to the lake,” 2021, cotton and acrylic yarn, 96 x 96 inches, courtesy of the artist and Various Small Fires, Los Angeles / Seoul.

Diedrick Brackens and his hand-dyed, hand-woven tapestries are rooted in the illustrious tradition and history of Gee’s Bend quilting and Ghanaian kente cloth, but always feel completely fresh and contemporary. The poetic, silhouetted figures, modeled after the artist’s own body, dyed the deepest black, popped against the bright salmon and turquoise at ‘s booth. It’s beautiful to see the way traditions come together in his work, all the while adding his own perspective and experience as a Black, queer artist from the South.

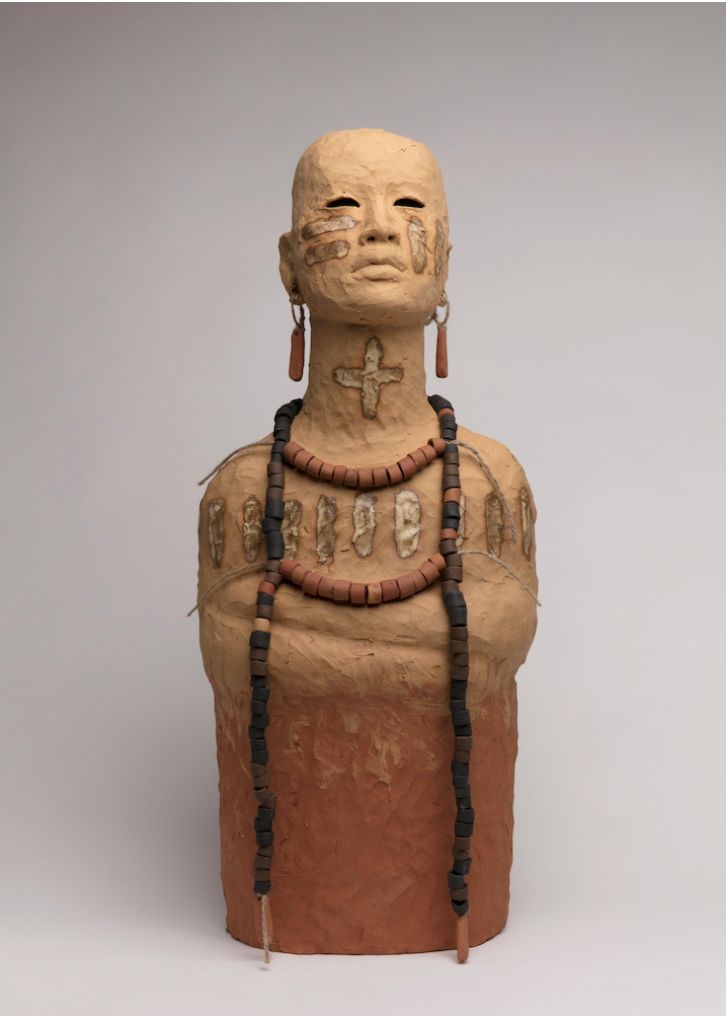

Rose B. Simpson, “please hold 1,” 2021, ceramic, glaze, and twine, 29 1/2 x 12 x 7 inches, photo by Addison Doty, courtesy of Jessica Silverman, San Francisco.

The way in which Indigenous, New Mexico artist Rose B. Simpson’s ceramic sculptures and androgynous busts, on view at , can at once conjure a post-apocalyptic future and feel centuries-old is remarkable. A member of the Pueblo of Santa Clara, New Mexico (Khaap’o Owingeh), her slab-based ceramic building techniques were passed down to her from her mother, a renowned native artist, and date back to the 6th century. They have a distinctive texture not often seen in ceramic work today. All the accessories and leather bindings are deliberate. Never one to waste, she reuses all the scraps to create the beads and embellishments.

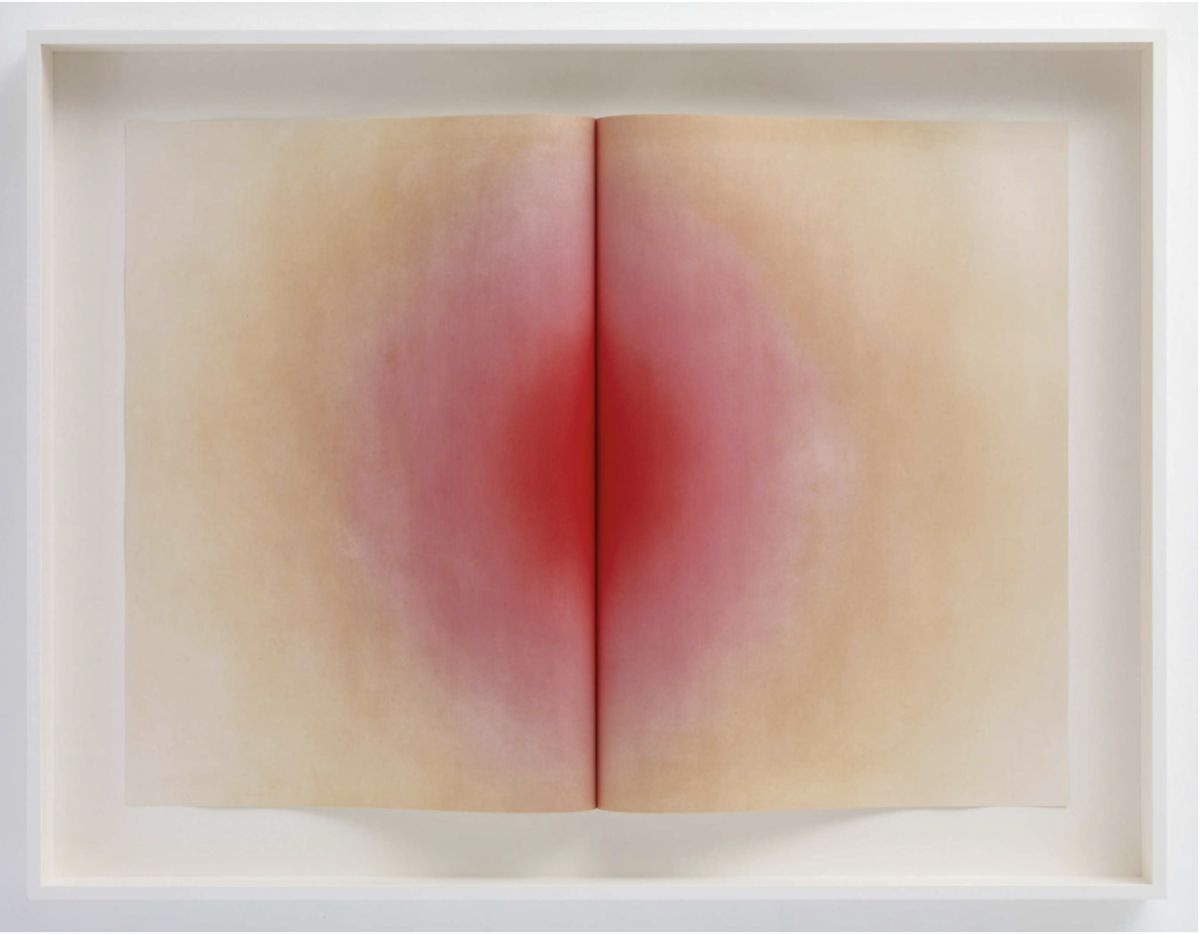

Anish Kapoor, “Fold I,” 2014, color etching on two sheets of 350g Hahnemuehle, mounted dimensionally, 61 ¾ x 47 3/16 x 5 1/16 inches, courtesy of Carolina Nitsch Contemporary Art, New York.

Anish Kapoor’s reflective mirrors are an art fair staple, but, hidden from plain view at , his Fold I from 2014—a color etching on two sheets of paper mounted dimensionally to appear like an open book—was absolutely enthralling in person. The fact that the subtle gradient of color (reminiscent of his recent body of work featuring gradient disk sculptures) and fine texture—almost like a delicate powdered blush—could be achieved through the intricate process of color-etching took my breath away.

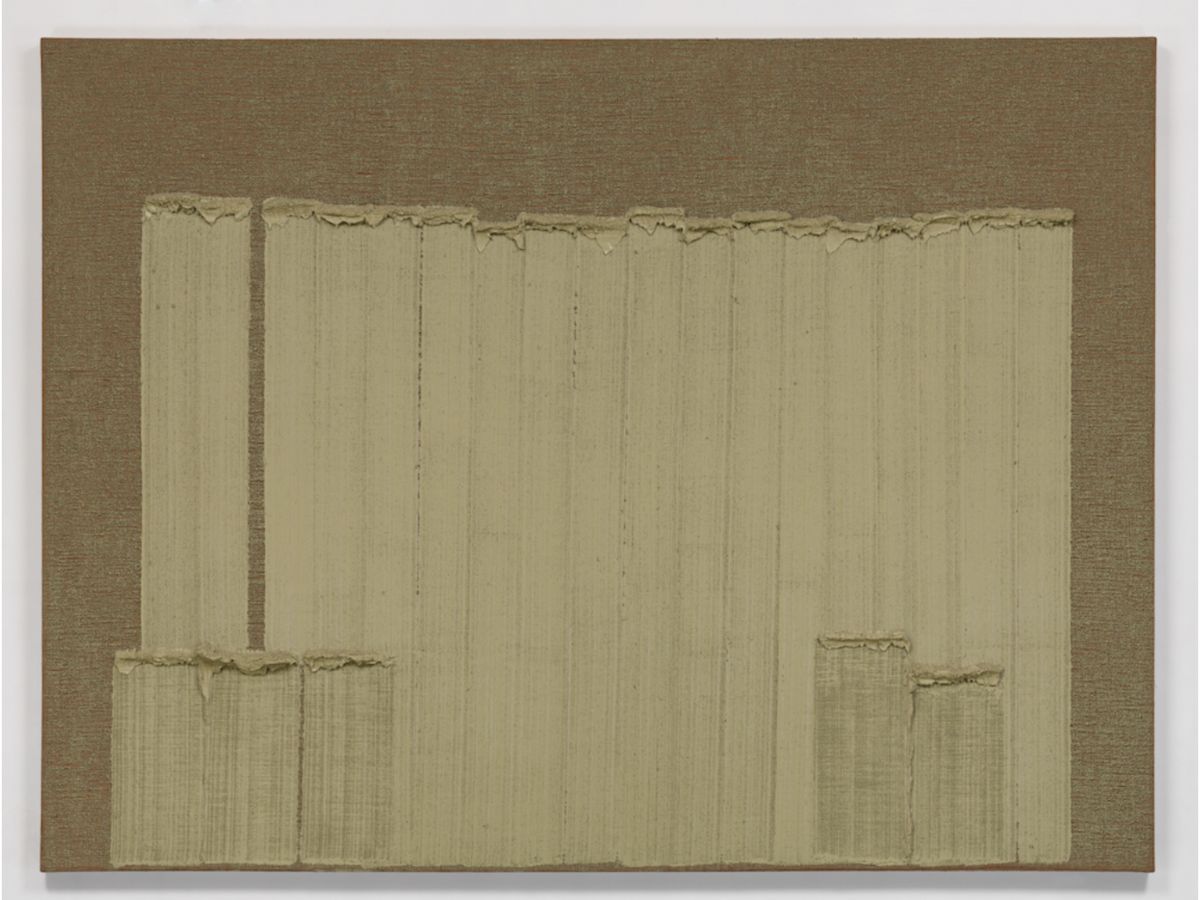

Ha Chong-hyun, “Conjunction 09-015,” 2009, oil on canvas, 76 3/8 x 102 3/8 inches , © Ha Chong-hyun, courtesy of the artist and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles/New York/Tokyo.

Blum and Poe’s booth had one of the best paintings of Post-war master Ha Chong-hyun, of the Dansaekhwa (meaning “monochrome painting” in Korean) generation, I’ve ever seen. The unique surface of his “Conjunction” series, first initiated by the artist in the 1970s, is achieved by Ha’s signature method of using a palette knife to slowly and methodically push the pigment through from the back of the burlap fabric to the front. It oozes from the hemp’s pores. He then elegantly scrapes the paint with the palette knife to create these characteristic waves of impasto. The work demonstrates the artist’s monastic daily ritual—a meditation of minimalism.