An Oral History with Nyeema Morgan

Bomb Magazine / Jul 26, 2022 / by Nate Young / Go to Original

Nyeema Morgan in her studio, Chicago, IL, 2022. Photo by Erin Morgan Taylor. Courtesy of the artist.

Nyeema Morgan’s artistic practice is informed by her childhood, as the daughter of two artists, her formal training, and continuous pursuits of freedom of expression. In this oral history conversation with longtime friend and artist Nate Young, Morgan unravels the layers of her identity and its significance to her work. Beginning with the serendipitous origin of their thirteen-year friendship, the artists outline her trajectory from Philadelphia to Greenville, NC, then Minneapolis, New York City, San Francisco, and, finally, Chicago. Reckoning with her understanding of place and belonging, ultimately, Morgan is grounded by a purposeful fluidity and creative spirit, a trait that she inherited from her late mother. Young’s admiration for Morgan’s work shines through in this conversation and together, they arrive at a comprehension of the significance of intentionally deconstructing material, language, and ideas as necessary processes in art making.

—Janée Moses, Oral History Project Managing Editor

Nate Young

I was trying to think about a good place to start…

We’ve known each other for thirteen years now. And the funny thing is that there are so many coincidental overlaps from before we met and even up until now. You were born in Philadelphia, and I was born just outside of the city.We even went to the same high school in Minneapolis—

Nyeema Morgan

—at the same time!

NY

But we didn’t know each other.We finally met in 2009 at Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture.Right after that, I moved back to Minneapolis and met my now wife, painter Caroline Kent, who knew your dad, also a painter, Clarence Morgan.He was her teacher in grad school at the University of Minnesota.

Caroline and I moved to Chicago in 2016 when I took a job at the University of Illinois. You and Mike [Cloud] moved here what, a year later?

NM

Close. We moved in 2018.

NY

On top of all that, now our kids are buddies, and next year they will be in the same elementary school!I find it all pretty amazing.I’d say I’ve been a fan of your work since we first met back at Skowhegan, and I think we also share a lot in common in terms of material and conceptual approaches.

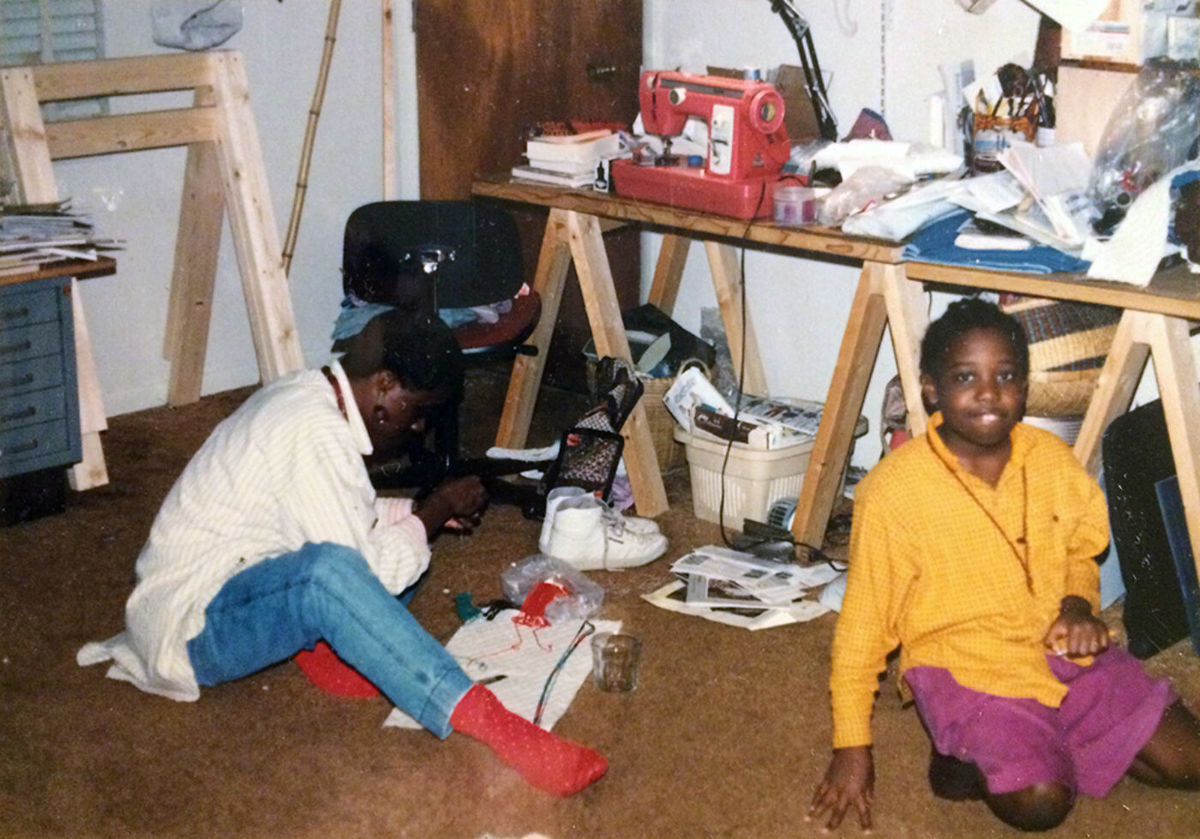

Nyeema Morgan at the Stratford Arms Apartments, Greenville, NC, 1983.

NM

I was drinking paint water as soon as I could walk. (laughter)

I’ve been in the studio my entire life. It was an extension of our living space, not just literally but figuratively. Having artist parents and inhabiting that creative space was all I knew so it seemed very normal. I took that for granted for a long time. Even now.

NY

Do you think your upbringing with artist parents impacted your choice to become an artist? Were your mom and dad, Arlene [Burke-Morgan] and Clarence [Morgan], supportive of your work?

But also, maybe a good place to start is to think about you at a young age because both of your parents were artists.In some ways, I’m kind of envious of your proximity to art from such a young age.I don’t think I had the idea that I would or could be an artist until probably high school.Maybe you could talk about what it was like growing up “in the studio” your entire life.

Clarence Morgan (the artist’s father) at table in front of Nyeema Morgan’s series, Soft Power. Hard Margins., Chicago, IL, 2021.

NM

In hindsight, I appreciate my upbringing so much more, but that appreciation required distance so that I could reflect on the access I had, and still have, to their creative energy; and the support I had, and still have, as an artist. I’m immensely grateful for that unwavering encouragement, which a lot of my peers don’t have, and I commend them for forging a path forward. I can’t imagine what it’s like having to justify and defend your work, your art practice, to your family.

NY

And you married an artist in Mike. The saga continues. I know for my kids, it’s normal for them to be in really close proximity to Caroline’s and my studios. We’ve had live-work space for pretty much as long as they can remember.When my oldest daughter was four and I was single, I had pretty much converted my entire apartment into studio space.

Were you an occasional visitor to your parents’ studio or was it similar to how it is for our kids: homeisthe studio, and the studioishome?

NM

Early on, home was the studio. When I was really young, when we lived in North Carolina in a three-bedroom apartment, my dad used one of the bedrooms as his studio. He was able to have more privacy. I remember a baby gate in the doorway and still being able to watch him work.

My mom didn’t have a formal studio. Her studio was really just anywhere and everywhere that she could make it—in the kitchen, on the living room floor stringing beads, making ceramics, drawing, you know? Because my brothers and I were at home with my mother, those formative years being in her presence and watching her make things, asking her questions, and participating in her creative work really shaped my sensibilities as an artist.

Nyeema Morgan and her mother, Arlene Burke-Morgan, at the Stratford Arms Apartments, Greenville, NC, 1987.

Once we were in grade school, they got their first studio, which was a steel storage unit. I think it’s called a Butler building: no insulation, concrete floors, very simple. That was my first exposure to a formal studio space—a makeshift workspace outside the home. And it was always full of work. I loved being there, surrounded by paintings, tools, and sculptures. It was paradise, endless curiosity, and fun. In the ’80s, my mom made these gorgeous ceramic, abstract, biomorphic sculptures. Many of them were bigger than me and were clustered throughout her space. I would run and hide between them—they were my friends. (laughter)

NY

We were both born in Philadelphia/the Philadelphia area.I never actually lived in Philly, and I moved to Minneapolis when I was pretty young.

NM

Neither did I. I mean, I lived there for the first two years of my life, but I have no memories of Philly other than going back to visit family. Philly exists largely for me through stories I’ve been told by my parents and relatives and other artists who’ve been longtime family friends like Winne Owens Hart and Bill Gaskins. Whenever my parents talked about their artist peers, they mostly mentioned folks or friends from Philly like Moe Brooker, who recently passed, or James Brantley, who they traveled with in Europe. There are a lot of great artists of that generation, born around the ’40s and ’50s, who came out of Philly: Barbara Bullock, Howardina Pindell, Barkley Hendricks.

Anyway, my parents and my relatives are characteristically “Philly” and I’m not quite sure what that means but I can recognize it when I’m with someone from there. From the way they pronounce certain words to a uniquely Philly no-bullshit matter-of-fact-ness. Recently, it seems like Philly is in the air. People mentioning their relationship to the city, like Black Thought’s anecdotes about growing up there or Christina Sharpe writing about her family being in Philadelphia before they moved to the suburbs.

NY

Your parents are your connection to Philadelphia. How do you think about the similarities between Philadelphia and Chicago regarding the art world, or maybe, also specifically, the Black art world?

NM

I don’t know. Like I don’t know the art world in Philly. I just feel like, for me, there’s been a mythology around Philadelphia that I grew up hearing from my parents, my aunts, my grandparents.I heard anecdotes that taught me about the politics of the city, and about segregation. They’re similar to the stories I heard about Chicago prior to moving here. So, I’m trying to understand Chicago, and through these similar stories, I’m drawn back to Philly.

My husband, Mike, is from here; so, he’s always told me stories about Chicago. He and I both have a familial kind of lineage to these urban places. I just feel like, synchronistically, Philly keeps coming up as I’m getting to know Chicago.

NY

Now we’re both in Chicago with our families.

NM

We moved here in 2018 with our two kids in tow because Mike got a full-time gig at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

The first year and a half was just us getting settled, and I was still spinning from my mom’s death in December of 2017, then boom! We’re in a pandemic. The reality that I’m here in Chicago is just setting in now. I’m trying to understand where I am and get a sense of the ethos of the city.

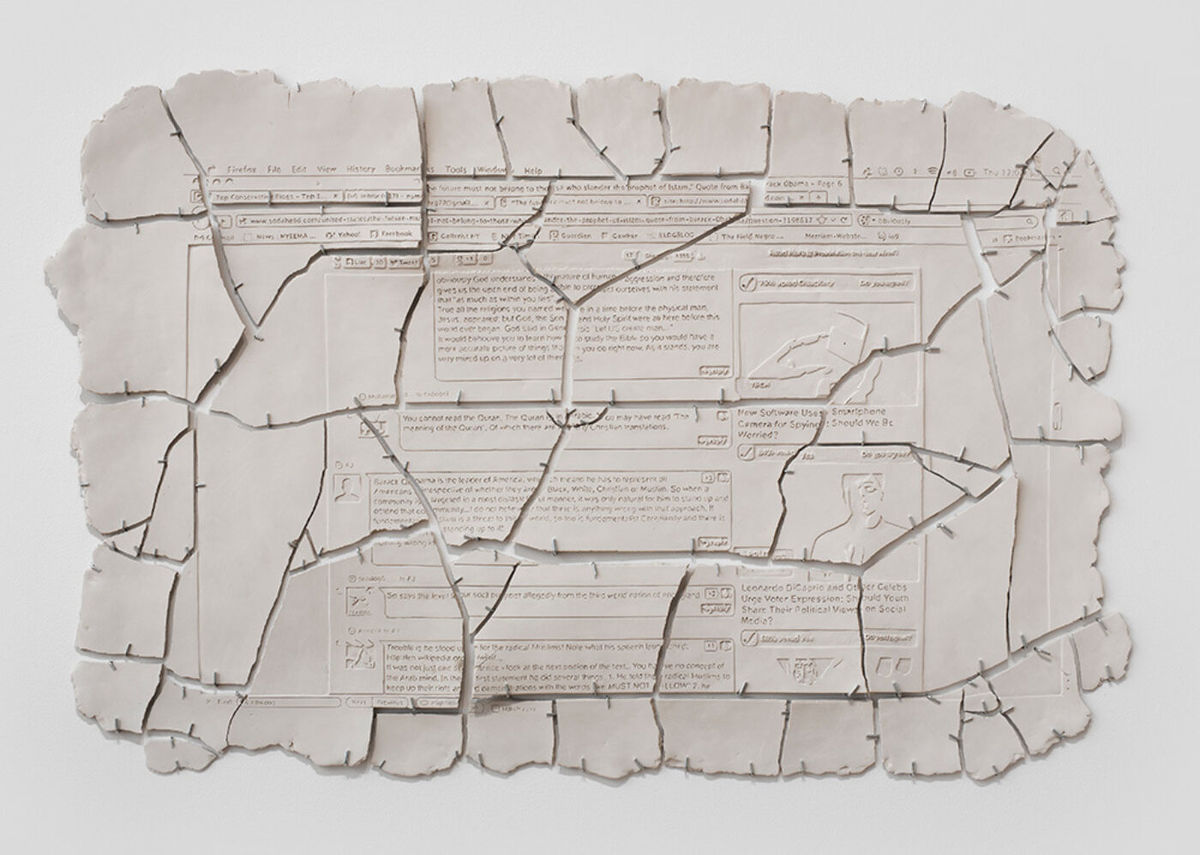

Nyeema Morgan, “obviously God," 2012, wall-mounted unfired clay with metal brackets, 35 × 50 inches. Photo by Andres Ramirez. Courtesy of the artist.

NY

Well, what have you made of Chicago so far?

NM

Chicago is a big city, bigger than I imagined. Having lived in New York City for twenty-something years prior and given my family ties to Philly, I’ve gleaned that these two cities are my basis of comparison. There are stark differences, but some parallels related to the Black experience in America.Mike is always telling me stories about Chicago that I’m trying to contextualize within a larger contemporary and historical narrative. You’ve lived in Chicago a few years longer than me, four or five years, right?

NY

Going on six now.We were talking the other day, and you were saying that thinking about Philly helps you grasp Chicago.What is it that you grasp specifically?How do you understand Chicago more through thinking about Philadelphia?

NM

I spend a lot of time thinking about how culture, community, and history are shaped. Maybe it has something to do with feeling like a nomad, not yet gaining a sense of belonging which, for me, is more tethered to lineage rather than a specific place. But giving context to that lineage helps me understand my family, my people, and the circumstances and decisions that led them to where they are now. Chicago plays an important part in our cultural history. Again, my understanding of Chicago has been through stories that vary depending on the source. I have the same kind of understanding of Philly: I wasn’t raised there but the city has such a strong presence in my family’s history. I can’t help but draw comparisons to understand what’s happening here.

NY

I’m going to shift and ask a direct question about your understanding of place. You say that you feel nomadic. Is there a specific place that you think influences you most?Or, for you, is it more a kind of sentiment like, It ain’t where you from, it’s where you’re at?

NM

Place plays a big part in shaping identity. My parents were born in Philly and they grew up in Philly. Their parents had moved there from various places in the South, and I see how the city of Philadelphia moldedtheir identity. I’m married to someone from Chicago, who lived in Chicago most of his young adult life. And his identity is very much shaped by his experience here.

NY

How has your own identity been shaped? Can you walk me through your trajectory? I want to map all the places you have called home.

NM

I did move around a lot. Two years after I was born, we moved to Greenville, North Carolina, because that’s where my dad got his first teaching job at East Carolina University.We lived there from 1979 until 1992.Then in 1992, he accepted a teaching position at the University of Minnesota in the Art Department in Minneapolis. So I only lived in Minnesota for about four years before leaving for college in New York City to go to Cooper Union.

I have a good friend who likes to introduce me as being from Minnesota because she finds that interesting. I always get upset because I don’t know anything about Minnesota. (laughter)I know nothing about Minneapolis, really.I don’t know my way around; I wish I did. I’m envious of people who have that rooted relationship to place.

NY

Oh! That’s interesting because I usually tell people that I’m from Minneapolis.I lived there for almost 25 years.It’s the place that I know my way around most. So, do you say that you’re from North Carolina? Philadelphia?I guess if I think about it, I think of you as from New York City, but I know you also spent time in the Bay Area for grad school.

NM

I say I’m from all over the place. My early formative years were spent in Greenville. But it wasn’t until I left my parent’s home to go to Cooper that my social world really opened up. I was eighteen so I was there from 1996. Then I decided to go to graduate school in 2005. I went to California because I wanted to be as far away from New York City within the continental US as possible. I just wanted a break, you know? I thought, I’m going to go to California.

Living in New York City post-undergrad was rough. I don’t know how these art grads do it now, especially the ones that aren’t from New York City. Actually, I do know—a lot of them have a financial support system. So, yeah. I needed to get away.

NY

Okay. So it was Philadelphia to North Carolina to Minnesota, then Minneapolis to New York City to San Francisco, then back to New York City. You went to San Francisco to go to California College of the Arts and Crafts?

NM

Yeah. But when I got there in 2005, they already changed the name to California College of the Arts. They dropped the last “C” for “Crafts.” I had a pretty romantic idea of the Bay Area, San Francisco, Oakland, and Berkeley as a politically radical, progressive place. In hindsight, that was naive. By 2005, the tech industry had firmly rooted itself there. The culture of the Bay Area was different than I expected. It was segregated in numerous ways, really hermetic communities. So I went back to New York City as soon as I finished grad school. That’s where all my friends were, where I felt the most comfortable.

Installation view of Nyeema Morgan, Like It Is, 2021, Philadelphia Art Alliance at the University of the Arts, Philadelphia, PA. Photo by Joseph Hu. Courtesy of the artist and the Philadelphia Art Alliance at the University of the Arts.

NY

Okay. CCA then back to New York City. When did you graduate from grad school?

NM

Yeah. 2007. I took time between undergrad and graduate school. I graduated from Cooper in 2000. I didn’t go to grad school until 2005, graduated in 2007, then back to New York City.

NY

What were you doing in between? Were you still making art?

NM

Still? I wasn’t making art before. No. I was a student.

I went through that post-art school slump, you know, where I had to process what just happened and reassess what I want to do and how to get there. I had to regain my footing.I was technically proficient, and there was a lot more I wanted to learn about using materials. Between undergrad and grad school, I had some fabrication jobs. I did some work at a hospital making facial prosthetics. I actually trained and became certified as a maxillo-facial prosthetist.

NY

I want to pin that because I want to come back to that in relation to thinking about materials. I’ll have to remember to come back to that.So, essentially, between undergrad and grad school, you’re working.You go to grad school, and then you come back to New York City after.

NM

Yes.

NY

When I think of your studio, or anytime I’m ever at your studio, you have a kind of steadiness to practice,like you’re always making. You’re not necessarily making a hundred drawings a year. It’s steady. It’s always making. It’s always progressing; it’s always moving from one idea to the next stage that you’re at.At what point did that really solidify for you?

NM

Yeah. I have to break that down a little bit, that consistency that you’re talking about. It’s interesting that you mention it because Howard Oransky just sent me the preface he wrote for the catalog for the show he’s organizing around the life and work of my parents at the Nash Gallery at the University of Minnesota next year.He recalled something that my mom said when he first met her in the ’90s. It was at a small artist gathering in Minneapolis. I never heard her say this, but it’s so her; it’s something she would say. He wrote that when they were going around the table to do introductions, when it was my mom’s turn, she said: “I’m an artist. That means I’m an artist in everything I do. I’m an artist not only in what I make, but what I think, what I feel, how I move, how I breathe.”

What I think you’re describing about my process is a similar kind of fluidity to my mother’s practice, that embodiment of the creative spirit. My mom was a much better artist than me even though she didn’t have a professional practice so to speak. What I mean by that is she rarely showed her work. There was very little attention towards what she was doing. But she explicitly said she could care less about that. Anyway, she was better in the sense that her analytic mind, her creative spirit, and her playful experimentation were active in every thing she did. So there really wasn’t a distinction that I could see between her life practice and her creative practice.It was all so fluid and so seamless. It was persistent.

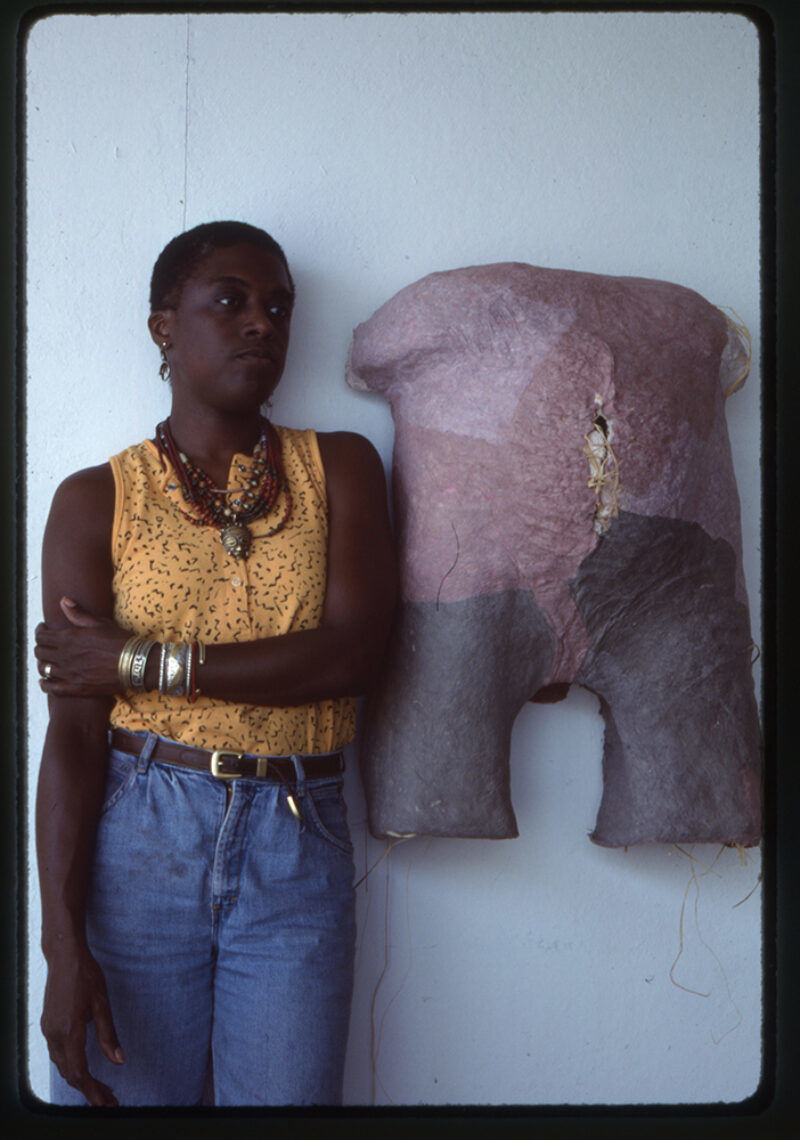

Arlene Burke-Morgan (the artist’s mother) in Greenville, NC, 1988. Courtesy of the artist.

NY

I knew your mom and dad really well. Let’s talk more about your childhood and your early art practice.

NM

When I was younger, my mother would teach me how to bake, and she refused to let me use the electric mixer. I’d beg, “Mommy, my arm’s tired; I feel like my arm’s going to fall off.” She would snap at me, “No, you’ve got to feel the resistance of the material.” Everything she did was so hyper sensory. So even in those things that she was teaching me, there was a deep attention paid to all aspects of an experience, which aligned with another one of her dictums—there’s a distinction between seeing and looking.That’s something that’s definitely embedded in my practice.

NY

I imagine that growing up as a child of two artists, your artistic tendency or your thinking about being—not only artistically, but as a parent, a person, a thinker, a creative, a blurring distinction between work-life—was influenced by both of your parents.

Nyeema Morgan in front of Clarence Morgan’s painting, Winston-Salem, NC, 1980. Courtesy of the artist.

NM

My dad had more of a professional work life and his time painting was his time. I wasn’t that emotionally close to my dad growing up but now as a parent and a peer navigating the art world, I really appreciate the camaraderie we have.

My mom was at home with us. She couldn’t really isolate herself from us, so we were really immersed in each other’s lives. My parents were young when they had my brothers and I relatively young in comparison to how old I was when I had my kids. They were in their 20s. They had my older brother when they were 21.

NY

Oh wow.

NM

They had me when they were 27 and my younger brother when they were 29.

NY

Your mother and father were the same age?

NM

Yeah, they were born in 1950.

To go back to the material, my mom taught me a lot about how to use material. She started off as a ceramicist and was also doing a lot of textile work, crocheted and quilted bags and hats. She made beautiful jewelry that incorporated her ceramic work and work with fiber material like raffia. In the midst of all that, she was always drawing; she was an interdisciplinary artist.A lot of her knowledge about materials came from her father. Papop [Gus Burke] was a blue-collar worker, a mechanic. He served in the Korean War. He had a tinkerer’s shop in the basement of their home in West Philadelphia. He was the guy in the neighborhood that you’d go to ifyour TV was broken. You would send it to Gus.If your toaster broke, you’d send it to Gus.

I remember he would have Mason jars screwed to the underside of a shelf,filled with screws and nuts and things. He taught my mom how to use power tools, how to build things. He taught her how to tie different types of knots which is something she taught me when I was about eight years old. (laughter) It was brilliant because my brothers and I spent the next seven days playing a game where we tied each other up using different knots and seeing how long it would take for each other to escape. That’s the kind of fun we used to have.

NY

It was also a way to occupy you so she could go work.

NM

(laughter) Absolutely! And then she taught me how to hammer a nail with just one hit. That kind of stuff.And how to cut through cardboard with a utility knife without cutting into myself. So I owe her quite a bit in terms of my understanding of material, my relationship to it. She was in such awe of material.

Nyeema Morgan’s studio, Chicago, IL, 2020. Courtesy of the artist

NY

I see you as a person who collects skills like, I want to know how to do that. You’re interested in how things get done. They may manifest in a work at some point, they may not—who knows? In the future, they still may.

NM

I think at the core of that is an interest in how things work. Not just mechanically but also why. What necessitates this or that? And that extends into our social world. I grew up in North Carolina. My mom wasn’t happy about moving to the South. In my family, there were unspeakable stories of things that happened to family members in the South. She didn’t trust people there and was very incredulous. In the culture of the South, there was a lot to refuse, especially not being from there. I grew up around the Confederate Flag flown right under the American Flag. My mom told me I didn’t have to stand up for the national anthem. I keep thinking about her practice of refusal, especially when it came to what people told us about ourselves or how we are supposed to be or how we’re supposed to engage with the world.

I remember coming home in grade school and telling my mom about some horribly racist stuff that happened, like the Black children being made to sit in the back of the classroom in this racist English teacher’s class or my brother getting detention for answering all the teacher’s questions when no one else would answer. How was that allowed to happen? What systems encourage that kind of abuse of authority, and how do those systems work? And my mom didn’t shy away from having those discussions with us.

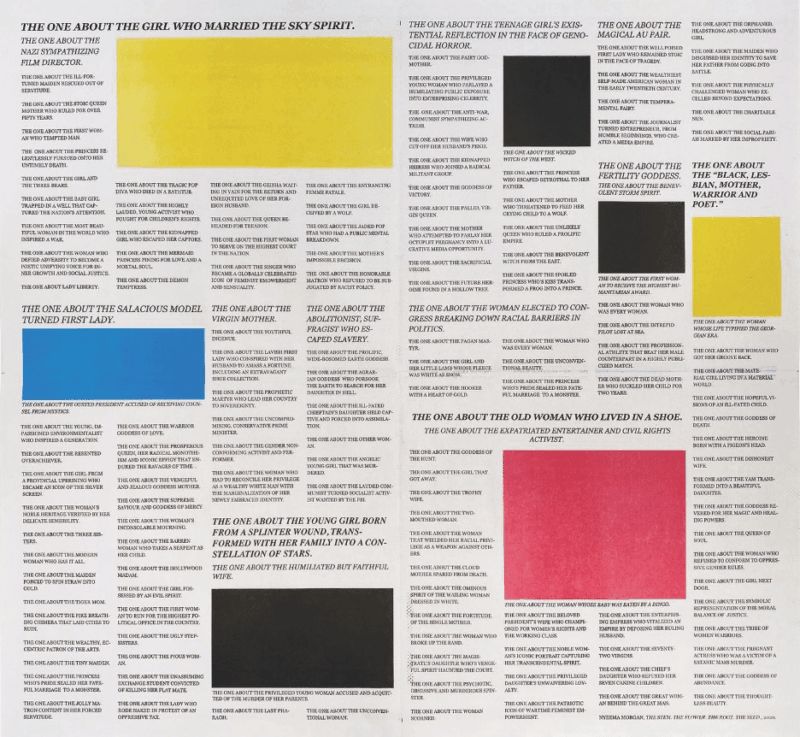

Nyeema Morgan, THE STEM. THE FLOWER. THE ROOT. THE SEED., 2020, wood, resin, and broadsheet newsprint. Photo by Wes Magyar. Courtesy of the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art.

NY

Damn.

NM

There were definitely times she had to come to school and curse somebody out.

NY

(laughter) I can’t see Arlene cursing anybody.

NM

Oh, but you didn’t know Arlene pre-Jesus. (laughter) It was a stark contrast between my mom pre- and post-Jesus.It was a major shift.

NY

Post-Jesus, she would just get quiet.

NM

Post-Jesus, she would get quiet and pray about it.Pre-Jesus, she would curse you out. She would curse at traffic lights and shoot you a glance that would shoot a dagger right through you.

NY

Thinking back, I could see it in her eyes though.

NM

Yes, an intensity and a practiced restraint. There was a restraint there. She worked very hard at that restraint. God bless her.

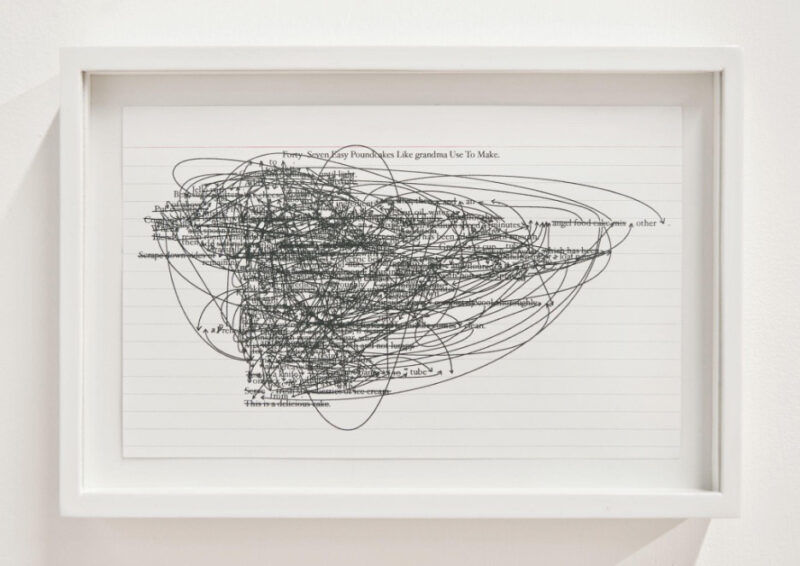

Nyeema Morgan, Forty-Seven Easy Poundcakes Like grandma Use To Make (7 of 47), 2017, inkjet print digital drawing on index card, 8 × 5 inches. Courtesy of the artist

NY

Also, as a conceptual artist, I can see the relationship between your attention to material, whether it’s sculpture or drawing or casting or graphite. The way that material works has a kind of parallel to the way we think about how being in the world works.

NM

Yeah. My studio work is guided by questions and observations. There’s no problem I’m trying to solve exclusively through painting or sculpture or drawing. I am excited by the different aesthetic registers of different mediums and how, when, why, and where those distinct differences are useful; and what effects they have on us. One of my favorite things to do when I go to a museum is to watch people looking at art. When most people are looking at paintings or photos or drawings, they tend to fold their arms or lock their hands behind their back. It’s a very defensive gesture. I think it has to do with the contrivance of the mark or images. But when looking at sculptures, people enter into the space of the sculpture with less hesitation. Sculptures as objects are similar to chairs and trees and cars which we interact with more frequently, more pragmatically. As an artist, I’m trying to make sense of our experience in the world mediated by the things we make.

So when it comes to my art practice, I’ve got to be all in. If I need to learn how to wire LED lights, I’m going to figure it out and do it, not just because I can, but I have a question about theatricality and spectacle and commerce and how luminosity evokes pleasure or desire. How does it bring life to these objects?

NY

And there’s somebody that knows how to do this: the Internet. These days, the Internet is the biggest help.

NM

It is.

NY

I always love talking to people who know how to do things. It makes me sit back and say, Let me just watch how you do that.

NM

Yeah. Me too.Like, I have to learn. It’s easier for me to learn, and I would have people come to the studio and show me things. Like, I could watch a YouTube video, but I can’t successfully figure something out just from that.

I have to have someone by my side, hands on, showing me. I need “what if” questions and

pauses so that I can take in the process.

NY

And then it’s like, Okay, let me try.

NM

Yeah, Let me try it. And then you mess up, and then you troubleshoot. My grandfather, Papop, died when I was about eight. But the times when he watched me, he would bring me into his workshop in the basement.He would give me these projects to do. He would give me, like, a clock.He would say, “Here’s a clock. Here’s a screwdriver.” He would give me a table and a chair to sit on and say, “Take it apart. Then I want you to put it back together.”This was a time when objects had seams and screw-holes, and you could tell where the object began and where it ended just by looking at it. Now, you’ve got this cell phone and it’s seamless. It’s immaculate.

NY

Well, if you open your phone, you’ve got a problem unless you take a picture of it at every stage, every screw you took out. I forget to take pictures when I’m deconstructing materials all the time. I’m old school, but I guess I should remember to do that. (laughter)

NM

Yeah. Through those exercises he gave me, I learned about organization. And really started to think aboutcausal relations through the mechanics of objects. I’ve always been a causal learner. I need the context. So that was also a profound moment in my childhood. This awakening where I became curious about the complexity of objects, of systems.

NY

I’m jealous. I never had that when I was a kid. I was just curious and liked to take things apart for my own satisfaction. I think my older brother also influenced me a lot because he was always taking shit apart and trying to put it back together. I remember him breaking stuff; and he would take bugs and dissect them at a young age.

Yesterday we were talking about the trap of making highly crafted things. Sometimes it’s a stumbling block that hinders the viewers’ ability to move beyond the surface, so the conceptual complexities are overshadowed by a pretty drawing.Sometimes that feels like a hindrance as opposed to a benefit. I think that it’s a benefit because of the parallels between ontological and social constructions, specifically ontological or social constructions of identity or being in general. Most of the time, your work is very highly crafted. Only when it needs to be. I mean, there are times when you intentionally rupture the nature of craft, but even that is like a highly crafted endeavor, you know? It’s carefully ruptured.If there’s a crease or a shadow or a cut or a scratch, that’s the scratch that you made.Conceptually, you have these ideas, or questions, about the way that meaning is produced, or the way that its social condition is constructed.And you create the work so that it points to the rupture in that ontological construction.

I wonder if there was a moment for you when that was really clear?At what point in your practice, were you like, Oh these two things—ontological and social—are the reason why?

NM

It was a realization that I came to by observing my own work and myself. Over time I was able to identify and understand maybe some questions that persisted. Those questions that were underlying a lot of the work I was making, both the good and bad work, concerns about being in the world and knowing the world and understanding. It wasn’t a point per se, but the maturing of my relationship to my practice, my questions, myself. You can’t really escape yourself.

Growing up in the US, there’s a moment of awakening where you realize that the social world is constructed in a very specific way. And that it doesn’t care about you, and that you are an abhorrent element within that structure. A structure that exists within an anti-Black system.

NY

Mm-hm.

NM

And you know that to be false; hopefully you’re taught that. Sadly, some people aren’t. But if you do recognize that fallacy and refuse it, you spend an exorbitant amount of emotional, spiritual, physical, and mental energy—shit, all of your being—reconciling that as you move through life. As I got older, I became increasingly aware of a system that was in place, that was so finely and deliberately structured, to exclude me, to discountthe lives of Black people.Not only to exclude, but to destroy the lives of Black people. So I became fascinated with those systems. I think at a young age, and maybe I hadn’t put two and two together as a young adult and student-artist, I had this fascination with getting beneath it and understanding the structure of things and seeing how they worked. For me, that fascination was scrutinizing language through storytelling, images, texts, and objects.

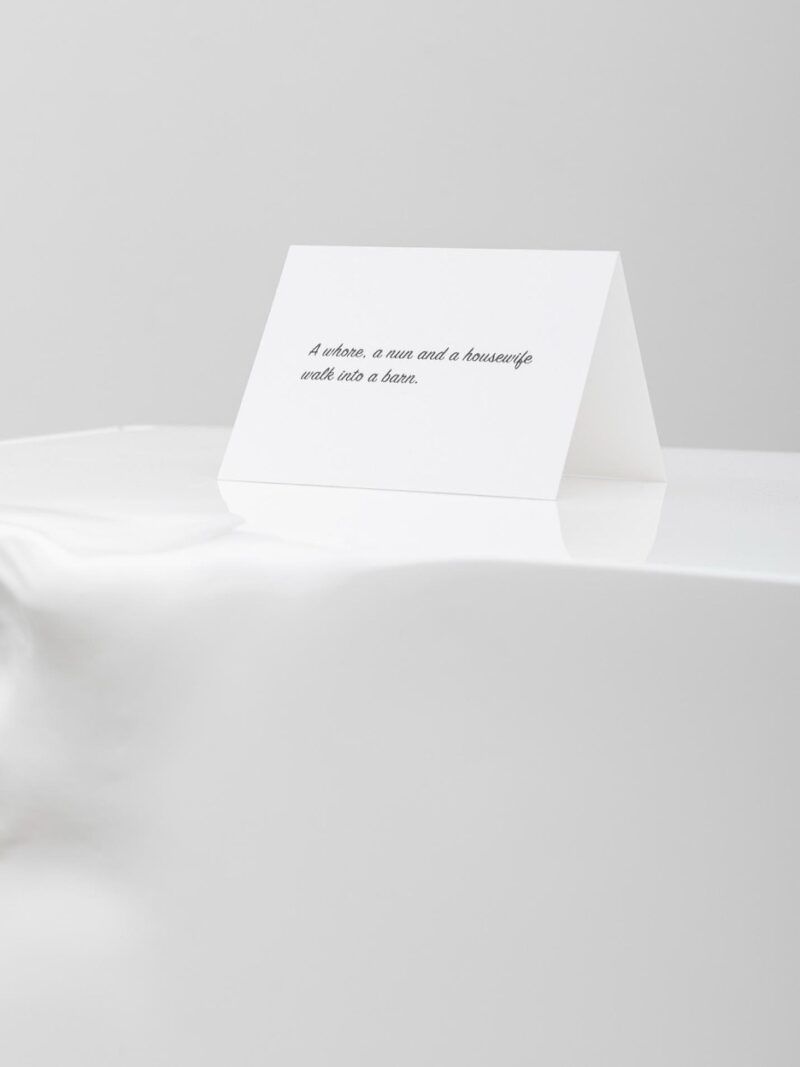

Nyeema Morgan, A whore, a nun and a housewife walk into a barn. (The Set-Up), 2022, wood, resin, lacquer, paper media, tools, 52.63 × 28 × 18.75 inches. Photo by Evan Jenkins. Courtesy of the artist and Patron Gallery.

NM

Yeah, rupturing surface is important. When I make things, they’re well put together.Not necessarily because I want them to be; that’s just my hand, early technical training before I went to art school. This also came from my mom, her learned relationship to technical mastery and precision. For a long time, I hated the rigidity of my hand. I wish I could just loosen up, you know?

NY

Yeah, yeah. My hand is rigid too; sometimes I just want to get like, I want to get free. When I see certain other artists, I’m like, How did you get free like that? And their hand just does that.

NM

There was a turning point where Mike said something to me that was really beautiful, and it changed the way I worked from there on out.He said that the way that you work is a blessing, not a curse. Jedi shit. He’s like, You just have to learn how to use it to your advantage.So, my focus turned away from resistance to understanding the significance of why I worked that way. And what are my thoughts, judgments, and questions about the mark of the hand, the presence of the hand, or its absence? And from there, a rhizome of questions about how we read sensuality.

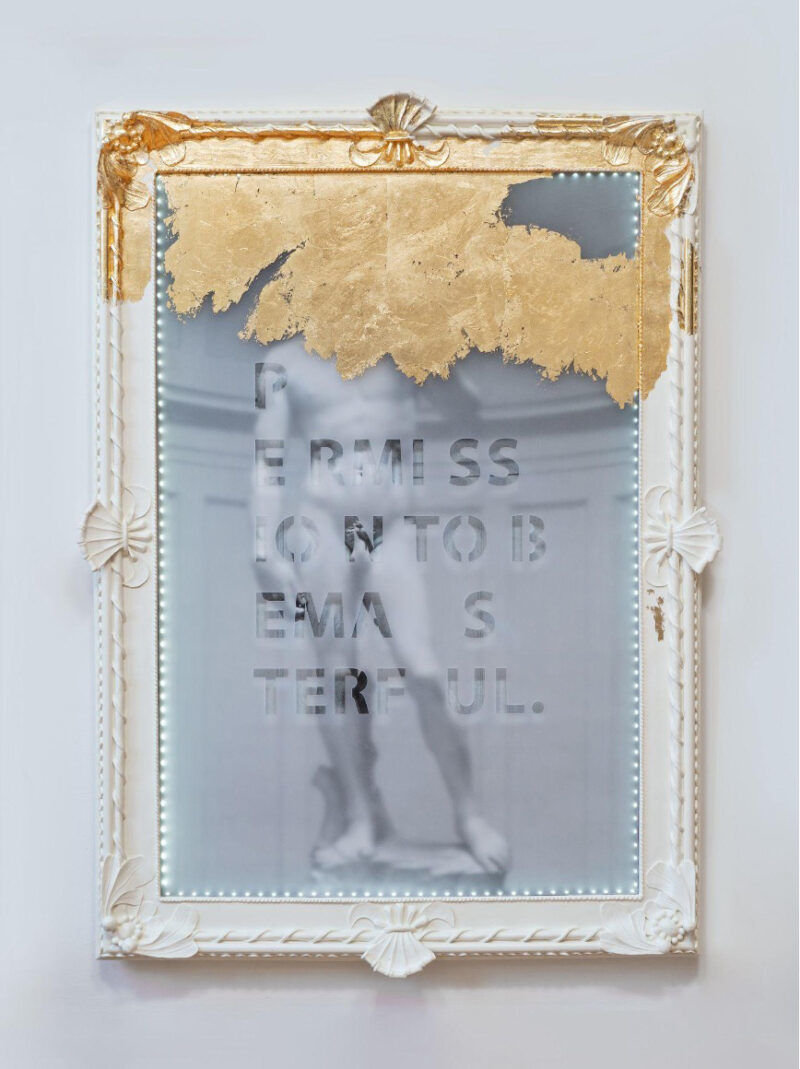

So, from that moment on, I leaned into it more, and it became a really interesting part of my practice, that I could fold into the subject of my work.How do I rupture this impenetrable thing at the surface where we first encounter it? How do I reveal its structure, how it’s built, the mechanisms at work? For me, Soft Power. Hard Margins. succeeds in that in many ways. The way that the resin spills out of the mold, and you get these plastic phalanges and flashing.

Installation view of Nyeema Morgan, Soft Power. Hard Margins., 2022 at Grant Wahlquist Gallery, Portland, ME. Courtesy of the artist and Grant Wahlquist Gallery.

NY

They’re almost like seams.

NM

It alludes to its making, to how things are produced or reproduced. Also, there’s the moments where the gold leaf isn’t fully on the frame and is on the surface of the plexiglass. All the individual elements of the work—the plexi, the canonic image, the LEDs, the plastic frame—are all visible parts of a whole. And at times, certain elements like the gold occupies a space outside of its conventional positioning. It’s a transgressive element, as if it’s insisting on its own autonomy.

NY

This relates to the question about the social construction of systems that are designed to exclude Blackness, Black people, from participation as full human beings.

NM

Yes, yes.

NY

Because they’re designed to be invisible. They’re designed to be seamless.

They’re designed not to be questioned. Sometimes, questioning that happens around them is also designed to support them.

I think that there’s a parallel between—one of the questions I had earlier had to do with the exclusion, or the way that Black conceptual production is overlooked a lot of times. Or maybe because it’s not always recognizably Black.

NM

I’ve had collectors say to me, “Oh, do you make Black work?” And my response is always yes. Then they would see my work and give me this look of confusion because they couldn’t grasp onto those common identifiers. They have a very narrow understanding of Black life. For them, there are no easy identifiers that they can cling to and fetishize. Take Charles Gaines’s work for example—you’re dealing with work that’s addressing systems of knowledge, categorization, and representation, or thought or processes related to ideas about identity. That took people a long time to acknowledge. Or Stanley Brouwn, whose work deals with movement, distance, and time, but has anyone talked about these subjects within the context of his experience as part of the African diaspora? As much as what’s happening for Black artists, right now, the art world still operates within white supremacist socioeconomic systems.

NY

Right.

NM

The capital. The capital that moves the art world is not coming from us. The ways that we’re rewarded for engaging in it are largely motivated by commerce rather than criticism.

NY

It would be difficult to continue to produce the way that you produce if you’re motivated by a reward within a capitalist art system. The reward comes from somewhere else.

NM

The reward must come from somewhere else and for me, it’s been internal. And that’s not to say that I don’t like validation. I love validation. That validation means more coming from you, coming from Mike, coming from my peers or those who don’t have a financial stake in the success of my work. That validation inspires me and touches me in a way no accolade or sale has ever emotionally stirred me. But also, primarily, an internal validation, you know, when I know the work has tapped into something. It’s hard to explain. You know, when I’m making my art, I never think about what people want, the desires of other people. Will they like this? I just assume that I, as a Black woman, in the 21st century, have the same kind of questions as other people out there in the world.

NY

I think that really has the potential to produce longevity because the market is fickle. If they like you today, it really doesn’t mean they’ll like you tomorrow.In fact, it doesn’t mean they’ll like it tonight.

NM

(laughter) —or this afternoon.

NY

Like, by the end of the day, the market’s tide could change.

NM

Kick us out of bed. Yeah.

NY

If that’s the motivation, what do you then do when the market changes its mind?

NM

You keep making art. I always tell people that my practice is question-based. There are observations and questions that precede any particular work I make.That’s what moves my art practice along. As long as I’m a living, breathing person in the world, I will keep making art. Only maybe a bit slower.

Arlene Burke-Morgan in her studio, Greenville, NC, 1988. Courtesy of the artist.

NY

But also, to go back to what Arlene said about the blurring of the distinctions, that she was an artist regardless of what she was doing, approaching life as an artwork. Could you send that to me some time so I could quote her to my class?

NM

Yeah, yeah.

NY

You know, even if you have periods of time where you’re not necessarily making, you’re still engaging the world with those kinds of questions.I might stop making for a while and just, you know, get a couple more horses and hang out with the animals. But the way that I would engage that is the same that I would engage the production of an object. I imagine that you find joy in making.

NM

Absolutely.I find joy in questioning, in the challenges of making, the moments where it’s difficult, the moments where things are smooth-going, even in the tedious moments. I really love the whole process of making, you know? The way that I love living.When I say “making,” it’s not just hands in the material, but it’s also periods of time that we might consider unproductive.For me, those are the moments where ideas are seeded and germinate.

Just as my mom said,

“It’s in everything that I do.”

NY

Yesterday, when we were talking about making, I was referring to engagement with materials, whether or not I’m making a sculpture or a dining room table or renovating my bathroom or fixing the sink or the dishwasher. Engaging material is something that is satisfying in and of

itself.

We also talked about drawing and turning into another state of mind. I’m thinking about yourLike It Isseries. Those are extremely laborious, in some way monotonous.Because when you’re drawing a shape—a black shape, a triangle—it doesn’t necessarily require the same kind of attention as rendering. It does require an attention to rendering in a way like pressure—sensitivity to the pencil in your hand, and the grip to the pencil in the amount of material that’s being laid on to the paper. It’s a different kind of attention. For me, drawing is a meditative activity.It’s not that my brain is off; it’s that my brain is in an altered state.

NM

In these drawings there’s large areas of value that I become immersed in for 5 to 30 minutes at a time. I get lulled by rhythmic scratching of the graphite on the paper. And it feels like free-falling into my subconscious. I’ve described those drawings as the connective tissue between other works that I do because in the process of drawing, I’m mentally traveling the space between older, recent, and potential works. Drawing to me is about process. It’s about being and presence. It’s about moving from one space to the next at any given moment. It’s about things, like a line coming into being, in the succession of movements. I’m a drawer. I identify as a drawer even though I do a lot of multimedia works. It’s not just because of the practice that I’ve engaged in with drawing, but it’s perceptual. I’m highly sensitive to delineations of space, more so than planar surfaces. Maybe that’s why I’m such a horrible photographer. So while I’m sitting here with this screen in front of me, its edges, its contours, are more pronounced.Again, back to those seams—where things begin and end. I’m more interested in that than the kind of planar field, even though I’m engaged with rendering these kinds of image fields but not for their own sake. For example, with my drawings, from a distance, they may look photographic; but when you get up close to the drawing, you see the aggregate of scratchy marks—it’s pretty raw. You can penetrate the surface.

NY

To me that sounds like freedom.The kind of freedom of the hand that we were talking about earlier.

NM

Maybe, in these micro-gestures.

NY

Because when I look at someone like Andy [Robert]’s paintings, I’m like, Oh, this is actually how Andy pays attention to the world, you know? And we all pay attention to the world differently. It has to do with the things that our mothers told us when she was showing us how to bake bread or cornbread or whatever.The things that we learned in school about rendering.

It sounds like from what you’re describing, there is a freedom of the hand translating the way in which you interpret the world.I think that you use that as a tool to think about, to go back to this ontological question, about being, you know?Being cognizant of the way that the world behaves,whether it’s socially conditioned or whether it’s the natural function of the change of seasons.

NM

Yeah.

NY

It’s interesting because there’s a kind of freedom that looks free, and there’s a kind of freedom that looks really contrived. But that also could be a kind of freedom because maybe freedom happens within some kind of boundary.You find your way outside of the boundary incrementally.The boundary is something that you can’t even see; you don’t even know where that boundary is because what’s on the other side of our perceivable reality is like, it’s a kind of nothingness—we can’t even imagine what aliens look like.They don’t have four appendages, arms, and legs. They don’t walk around like inStar Trek; they might be more like microbes or bacteria.

NM

We’re probably breathing them in right now. (laughter)

NY

Right? They’re giving us cancer. In Star Trek, there were two-dimensional beings, and they were like, fucking up the Enterprise. I think it was Data who finally figured out how to communicate with them. They had to turn the computer sideways and then they could see them.

NM

My mother got me into Star Trek. My parents loved all of those series. They grew up in the Space Age and were enamored with all of that. Any time there was anything sci-fi on—Plan 9 from Outer Space,Night of the Lepus, Doctor Who—we were sitting in front of the TV watching it. The speculation about what the future looked like, a technological advancement, or life beyond Earth—they were fascinated by all of that.Going back to what you were saying about freedom and, as you asked, “What’s on the other side of our perceivable reality?” That’s the hope and optimism of Afro-futurism.

NY

Science fiction is always asking philosophical questions.

NM

Yes. To give more context, my mom’s mother, Grandma Alease, was very strict. Whenever they went out, they walked in a single-file line, dressed presentably. My grandmother didn’t tolerate any kind of frivolities other than art, specifically music and singing in church. I didn’t find out until decades after she died that she wanted to be an opera singer. I had no idea. It broke my heart. She wanted to be an opera singer,which gives so much more emotional heft to read a book about Marian Anderson that she gave me when I was about five or six. So my grandmother’s love of singing and music was encouraged in her children, all five girls. They all sang and played instruments. My mom played five instruments.

NY

What did she play?

NM

She played the viola, the violin, the piano, the guitar, and something else.She played all those instruments. She also was a voracious reader, not being very social, even as a child. I think that was her escapism: her imagination. Her inner life was so rich. So a lot of the books that we had in our homes were my mom’s. She didn’t care what we read. I remember reading Native Son when I was eleven or twelve, then The Bluest Eye.

NY

That’s intense.

NM

Yeah. Of course, at that age, I couldn’t grasp the full context of what was going on in those stories, but it was enough to leave an indelible mark, a caution to be wary of the world. My parents definitely didn’t coddle us. I mean, one of the songs my mom used to sing to me at bedtime was “Strange Fruit.” But I don’t want to paint a picture that she was morose. She was a joyful person who acknowledged pain and suffering as well. She didn’t want to conceal that from us, but also had a way of teaching, well at least me, not to be afraid of it. That pain and suffering is something that can be passed through, that can be transcended.

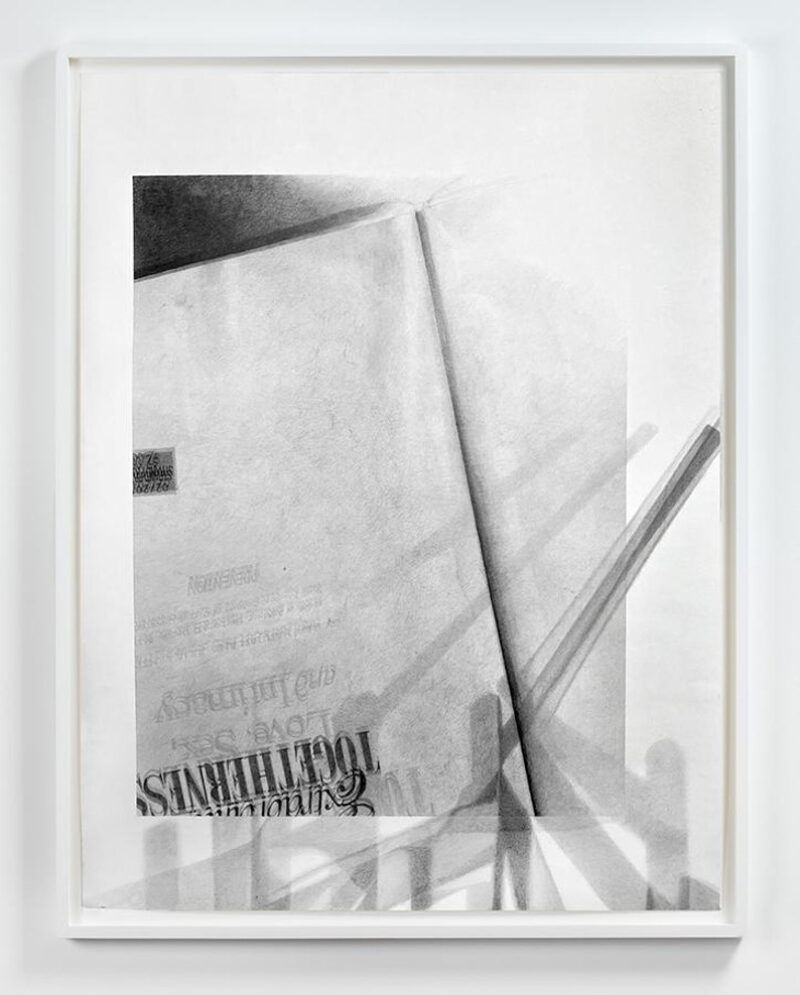

Nyeema Morgan, Like It Is: Extraordinary Togetherness, 2021, graphite on coventry rag paper, 38 × 50 inches. Photo by Joseph Hu. Courtesy of the artist

NY

Yesterday, you were talking about, initially or for a time, hating your hand, and then realizing how to use it as your own conceptual strategy. I think that’s the sensual conceptualism. Could you explain?

NM

That’s a term that Mike brought up in a late-night impromptu studio visit. That’s what happens when you’re married to another artist. They come meandering into your space and poking their nose in your business. (laughter)

Anyway, he honed in on an aspect of my work—its sensuality. He reads my use of text as one of several layers of sensuality, unlike how [Joseph] Kosuth used text. In my work, what leaves an impression for him ishowone reads sensuality of surface, material, and form. He came up with the termsensual conceptualism. I like that. It folds subjectivity into a post-conceptual language that warms it up and isn’t so hierarchical when it comes to material, idea, and process.

You can’t ignore the sensuality of this material—how we read it, how it operates on us psychologically, emotionally; and at the same time, not being able to let the viewer just walk away from it but makingthem aware that it is operating on them, reading it in a very particular way.A super particular way.

NY

A lot of conceptualisms can be really dry, and I don’t think of dry as a pejorative term. Actually,I prefer a dry white wine and gin and scotch. I like that dry, harsh feeling in my throat.

I remember one time when I was a grad student, I asked Charles [Gaines] how he reconciles conceptualism with either the desire or the impetus, or maybe just happenstance, of making it a beautiful drawing or beautiful object.He said, essentially, what you just said: that the beauty—I always put beauty in quotes—the “beauty” is actually part of the conceptual strategy in the work.

The way that someone perceives the work as central can be a strategy of the work, and that maybe gets to the idea of conceptualism.

You hope. I wonder if you have this trepidation—I don’t want to call it fear; it’s more like cringe—of being concerned about whether or not the audience moves beyond the surface-level sensualism. It’s like, some might see that drawing, that drawing you’re working on behind you, as a beautiful object, and that’s enough for them. Then they stop there, and that always concerns me a little bit.

NM

If I’ve done my job well, they won’t be able to stop there. That’s what I’m always working towards: to deny the viewer the privilege of stopping there. You can’t ignore the ruptures, the unsettling things that maybe shouldn’t be there. The shadows, an opening in a pristine surface, a spill.

NY

Exactly.Maybe you’re more optimistic about the collective ability to use common sense.

NM

Look, what’s so beautiful about works of art is the intimacy of the experience of it, not through reproductions but a live experience of the work in a shared space and time. I think it’s harder for people to lie to themselves in that quiet, intimate space.

NY

I also think that there are times where the aesthetic choices in the work are operating in order to form the way that people are thinking about the work, and they don’t know it.They may articulate it, but they don’t know how to operate it.

So they end up just saying, “It’s a beautiful drawing.” or “Wow, you could really render things. Like you’re really good at doing that.”Because the thing, the thing that the shadow is doing outside of the border, they can’t articulate what that makes them think or feel.

NM

I don’t think it’s a response that has to be articulated. And recognizing, first, that you are affected by the work, and second, maybe,howyou are affected by it, if at all, takes time. It takes, ideally, a longer amount of time than the time spent in the presence of the work of art. Days, weeks later in its absence, it’s still got a hold on them in some way. They’re still trying to think about what it is that they experienced, or what those kinds of thoughts inspired in them, or what it opened them up to.

NY

It sounds like you would have more trust in the work, maybe.

NM

I do. It depends on the work, you know? Because sometimes it’s working on the new sculpture that incorporates the joke, right?I’m still thinking about it as I go; I’m still figuring it out.

Nyeema Morgan’s studio, Chicago, IL, 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

NY

I think about this a lot. There’s some overlapping in the ways that we negotiate material and ideas.Oftentimes drawing is thought about as preliminary. As someone who makes a variety of different kinds of things, including sculpture, we just focus on sculpture. Drawing, then, is preliminary to the production of a three-dimensional object because it’s a plan, like an architectural plan to produce an object.You don’t draw like that. Your drawings don’t operate in that way, I don’t think.

NM

No, no. Because a lot of what I make, like the new sculptures, I don’t know how they’re going to look until well into the process of putting things together.So I only do a sketch if someone wants to see some vague description, or if I need to remember some formal thing I want to consider. But it’s a note of sorts rather than a guide—oh, it’s kind of like this, but it’s not going to be like this.(laughter)

NY

Right, right.You start making something and you have an idea it’s going to be this thing, and you have this LED component, and the image and text are going to interact in some way.

NM

The beginning of that work was kind of a propositional thing—can I make a work where I play with the hierarchical legibility between image, object, and text?It’s a question that I can recognize beginning with a work I made in grad school,Forty-Seven Easy poundcakes Like grandma Use To Make.

NY

Yeah. I invited you to show that work at the Bindery Projects.

NM

The rule-based, digital drawings printed on index cards. Anyway, withSoft Power. Hard Margins., I usedvery specific images, canonical art works, specific text that I wrote, and the objects, the illuminated, gaudy frames. And I have no idea how to adjust the elements of the work from one to the next, because there are 40 in the series, until I’m making it. How do you knock back the legibility, the prominence of theMona LisaversusErased DeKooning, which is easier because you’re dealing with the absence of image?So although there’s a high level of rendering or fabrication, there’s a great amount of improvisation.

NY

It’s frustrating that there are commissions and curators who ask, “Can you tell me exactly what the work is going to look like?” Umm, no?

NM

I love working with curators and gallerists who are sensitive to the different ways that artists work and that there needs to be allowances for working in the moment. One of the things I really loathe is when someone says during a studio visit, “I don’t know where this is going.” I mean, why would you?

NY

Right, right.Would you ask Charlie Parker, “Tell me about the song you’re going to play?” (laughter)What’s it going to sound like?How long is it going to be? When is it going to stop?

NM

I don’t know! Just trust me.I guess one of the things we’re trying to do professionally is garner trust, which is contingent on the work. Trust me. Walk with me.

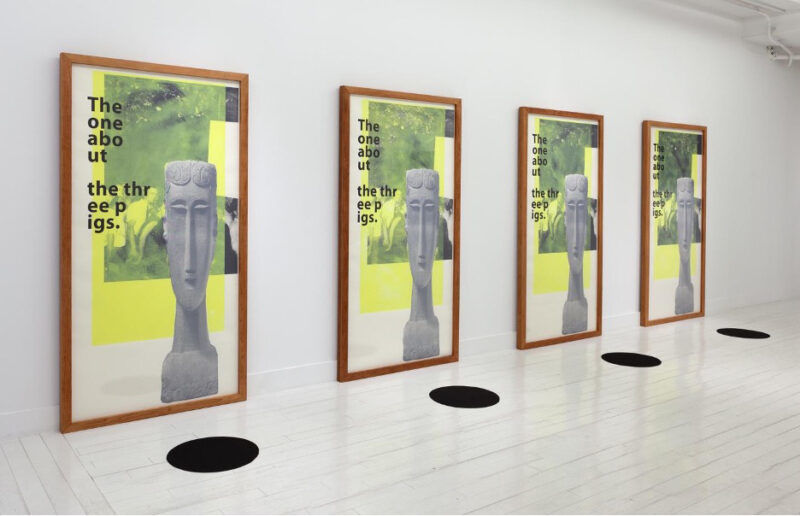

Installation view of Nyeema Morgan, The Set-up, 2022, Patron Gallery, Chicago, IL. Photo by Evan Jenkins. Courtesy of the artist and Patron Gallery.

NY

In your show,The Set-Up at Patron Gallery, there’s theLike It Is drawings, the small horror horror prints, and the two sculptures, right?

NM

Yes, and I made the last-minute decision to show the four largehorror horrorprints I made four years ago, the near-identical prints that I showed at Marlborough Contemporary.I’m on the fence about whether I want to include them in the conversation that’s being created between the sculpture, the prints, and the drawings.

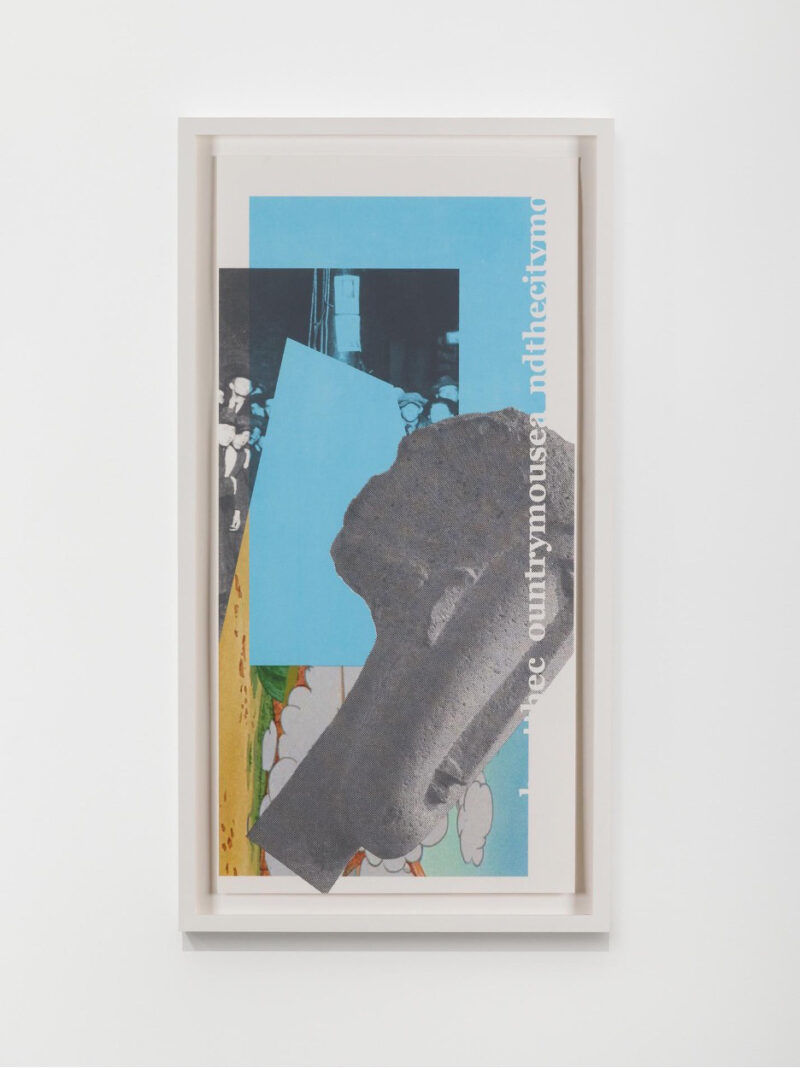

Nyeema Morgan, horror horror III, 2022, silkscreen with digital print, 14.5 × 30 inches. Photo by Evan Jenkins. Courtesy of the artist and Patron Gallery.

NY

I actually feel weird about my show because it’s just all drawings. Sometimes I feel like I need another—I call it a “move” in the space. Because as it is, it’s all drawings—it’s one move. There are no other aesthetic moves.

NM

There are a lot of things happening in those works besides the drawing. Like the undulating cut edge of the vellum and the lower edge hanging and curling outside the frame, you know? Also, you’re not just rendering a space within the drawing, but the drawing itself has a relationship to the space it’s in as well. Last year, I had a show at the Philadelphia Art Alliance. It was all drawings in the central space. But the architecture of the space was so specific, this Italian Palazzo-style building. It’s a historic building that created a very specific conversation with the drawings that I didn’t anticipate. That wasn’t my “move.” It was a condition of the space that added to the conversation with and among the works. But when you’re showing in a commercial gallery, those tend to be more conventional white-box situations. So, there’s not so much that you can do unless you’re explicitly addressing the space.

NY

Right, right. I guess that’s the word. Like it feels very conventional. Frame on the wall.

NM

Sure, but where are they on the wall? It doesn’t always have to be at the 61-inch sightline. Do you know what I mean? I’m thinking about that with my show, at Patron, specifically, the relationship between the drawing and the smaller prints, so, rather than having everything conventionally, maybe at the height of sixteen inches, maybe emphasizing a certain proximity between a specific drawing and the print. You know that same relationship happening somewhere else in the space, but being slightly shifted. Then it becomes this intentionally read decision about the proximity of certain images. With your drawings, why do they all have to be on the same sightline? What happens if the drawing’s framed and it’s three inches off the floor and challenges the accessibility of the image?

NY

Often times, when I think about putting an exhibition together, especially a solo exhibition, the exhibition is already pretty made in my mind and I’m like, this goes there, that goes there. This needs to be in front of that or that needs to be on top of that or across from that, and then everything works around one central idea. Do you have your show laid out?

NM

No, not at all.

NY

Really?

NM

I’ve seen the works in my studio, in proximity to one another, and there’s certain works that respond to each other in a striking way. Let’s say, a particular Like It Is drawing and a horror horror print. But that interaction needs to be fine-tuned in a way that I can only determine in the exhibition space and in the context of the other works—how close are they to one another? Which room? Which wall? Because there are so many things at play there. Whether it’s lighting, a peak of natural lighting coming, where the opening is or where do bodies come through, like what do you encounter first?

NY

Sightline.

NM

Yeah. I need to take all those things into consideration. I have a general idea, but I never know.

NY

I want to start with a question about the way in which stories are a form of knowledge production. The stories that we were told informed the way that we understand the world. In your work, you think about those systems of knowledge production. In the recent press release, there are a series of questions: Who gets to tell those stories? Who is the author of those stories? Who produces the system in which we understand how we operate, how we understand the world?

Those are the questions. If the question is about the proponent of knowledge production in historical storytelling, or even cultural storytelling in film or literature, who authors those systems of knowledge production?

Nyeema Morgan, The Flower, No. 3, 2020, broadsheet newsprint, 22.75 × 25 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

NM

Culture is an amalgam of agreed upon practices and stories that we tell ourselves about ourselves, whether they’re fictitious, historical-telling, fables, mythological. We use these mediums to script our identity. These stories, particularly accounts of historical events, can’t be expressed in their entirety. They’re biased, but towards what or whom? That’s where we get back to the instrumental use of storytelling. Who’s at the center of this universal subjectivity as narrator and inheritor?

NY

Right.

NM

As an artist, I’m interested in art history as a subgenre of history which is similar in motivation, structure, form, and function to the larger stories that we’re told.

NY

Yeah. To take it back to your work, I’m going off-script here, a little bit. I’m curious about the way that you’re questioning stories in general, like in life, and how you apply that to the questions that you start in your work. You say that you always start with a question.

Can you think of an example, in the work, of how you apply that way of thinking, of scrutinizing, or being suspicious about the stories that are told and inform the way we think about the world around us?

NM

You know, Mike went to Yale for grad school. He’s always telling me these stories. He has a story about Mel Bochner; I guess Mel Bochner is quite the storyteller. Anyway, as told by Mike, Bochner told his class this story about Dan Flavin, a story about him not being in communication with a curator he was supposed to be working with to put on a major exhibition of his work. The curator was really upset so months before the exhibition, he travels to see Flavin.When he gets there, annoyed, Flavin’s studio assistant tells him, “Dan’s upstairs, watching football,” soccer or whatever.The curator goes upstairs to see him and Flavin nonchalantly takes a pen and a piece of paper, and draws a little diagram, and says something to the effect of “Get this light, this light, and put this one here and this one there—here, that’s the show.” Factualness aside, it doesn’t really matter, you know?It was a story Mike told me to express the idea about the integrity of artistic genius and how the artist shouldn’t be beholden to the institution. But when he told me that story, my immediate response was, What am I supposed to do with that? You know, all that glorious art hero machismo bullshit. (laughter) As a woman, and a Black woman, I couldn’t find any use for that story. Do you know what I mean?There’s no way I could do that. I wouldn’t be a hero; I’d be “difficult.”

That story is put to use when you tell it to students or other artists so they can activate its meaning by applying it to their own lived performance of the artist’s identity. That’s why Bochner told the story to his students rather than telling it to his family over the Thanksgiving table.

NY

Because the story presumes a white male archetype.So, the story, operates as part of a system, as far as it tells an artist how to behave.Underneath the story is the presumption that there are no artists other than white males.Yeah, the recipient of that information, of that knowledge, are people who can put that to use in their lives; that’s not stated.

NM

The value of those stories is contingent on the identity of the receiver and the person’s ability to reap the rewards for adhering to the rules of participation. So, if you’re a young white guy painter who wants to take up the mantle of abstract expressionism, have at it—that’s your legacy. But if you’re a BIPOC artist—

NY

—you have a keen understanding of what the story leaves out, or what the story presumes.

NM

Well, we live in a social world that is politically motivated.

NY

So, for instance, in the series of drawingsLike it Is, where you’re photo-copying book pages, and then you create an enlarged drawing of the photocopy, it moves the text and the object into abstraction. Rendering of it reinforces even further abstraction.Is there a way in which you apply that kind of keenness to the narrative, and what it presumes? To the structure of that work?

NM

By drawing the title page, the para-text, you don’t have access to the content of the book. I’m reconditioning your relationship to that content material. You can’t move any closer to the content, but you can move through several layers of the image because the surface isn’t as shallow as it may appear. With the empty space, shadows from outside the picture, the image of the book and the black space of the machine, constitute the surface of the drawing.

Nyeema Morgan, Studies for ‘Like It Is: Extraordinary Togetherness,’ No. 02, 2016. Courtesy of the artist.

NY

The surface of the story you were just telling about the artist, about the genius of the artist as essentially in opposition to the structure of the institution, is that the surface of the story? What’s beneath that surface of the story is the presumption, a set of permissions, that any artist can work that way. And artists should work that way. That excludes women, especially Black women, and people of color in general.

NM

This is what Adrian Piper was alluding to in her essay on art world politics where she says freedom of expression isn’t a right, but a privilege granted to a legitimate subject of rights. Well, who is that “legitimate subject”? The presumption is that the recipient is an idealized subject.

Back to the Bochner story, it is the inheritor of the dominant artistic legacy. Beneath the surface of that story is the instrumental function of the story, and in that lies the social and political power. I’m curious about how form, aesthetics, and meaning key into our ideological structure. It’s a structure that’s hidden beneath the aesthetic form of the story or the joke or the work of art.

NY

The analogy may break down. Can you identify the power within the structure of, for instance, the way that you’re thinking about the Like it Is series?

NM

If I’m understanding your question correctly, it’s in the conventions of how we read and construct images and conventions of representation, how images and information move through the world.

NY

And the book, I’m kind of thinking of the object—

NM

—within that body of drawings, I’m focusing on books with the word extraordinary in the title. They range from anything like self-help to how to play a better golf game to law books. The specificity of the book doesn’t really matter, or the word extraordinary for that matter. The word is an anchor and flows through different uses and different contexts.

NY

Right, right, right. Because I was thinking about the object, or the system of publication, as a location of power. Also, the word extraordinary itself puts the book into the context of authority; it causes one to think of the book as an authoritative object. I mean, it already is an authoritative object.

NM

Because it’s in print, it’s published. The focal point is the context of the image, information, and reading. In the drawings there’s a lot of uneven “margin space” on all sides of the image. Sometimes there’s just as much, or more, empty white space as there is drawing. But rather than it serving as a neutral, unoccupied space that registers the image, it’s a space that can be occupied by an image, the shadows. For me, it feels transgressive like when I was younger and would doodle in the margins of my textbooks.

NY

Yeah, yeah, yeah. So this leads me to another question in your work. I would say, often, if not always, there’s an interplay between text, image, and object. I am curious how you think about the relationship between the three.

NM

Looking back, I could see that I was interested in the relationship between text, image, and object. I already brought this up, but Forty-seven Easy Poundcakes Like grandma Use To Make is really significant, not in the emotionally cool, didactic way Kosuth was thinking about representation.

The drawings were digital rule-based drawings where I edited 47 easy pound cake recipes into one another beginning with my grandmother’s recipe. She died while I was in grad school. Even though I couldn’t articulate it at the time, I was curious about how my personal experiences and exposure to the world shape my work. That line of questioning continues years later in works like Soft Power. Hard Margins. where I’m thinking about the primacy of those elements.

Nyeema Morgan, Forty-Seven Easy Poundcakes Like grandma Use To Make, 2007–2012, The Bindery Projects, Saint Paul, MN. Courtesy of the artist.

In grad school I gravitated towards working with text. Again, I wasn’t sure what my questions were; I was just messing around. Then I went to a [William] Pope.L lecture out in the Bay Area sometime between 2005 and 2007. He said something about, and I’m poorly paraphrasing, human beings. We loved to categorize and read things, tried to make sense of things. From that moment, whenever I encountered text, I tried to look at it formally first before reading it. It was a little game that I would play.

NY

I was thinking about the difference between language and text. But I remember in a different conversation you said you’re not necessarily interested in language, but you’re interested in text. This clarifies that for me—you’re thinking about text as image.

NM

Formally.

NY

And you’re also thinking about image as object. Image is part of object. To go back to the drawings, in this series Like it Is, there are images, but they’re an image of an object. But then, the object also refers to the site of its production, to the studio. And also, it’s an image of a non-object, too. Because the blank space is actually the space of the printer bed, or the shadow, and the shadow refers to the site of production, to the studio. So it’s an image of an object, the book, but it’s also an image of a non-object. It’s interesting to me to think about an image that’s not based on an object, but it’s not a pure abstraction.

NM

Yeah, and I’m definitely trying to push it in that direction, or at least play with that boundary. Maybe this relates to my generation who didn’t grow up with the Internet or a computer. My relationship to the virtual, to virtual reality is… You mentioned “pure abstraction” so I’m thinking about the objective world versus the subjective reality of the mind. Is the virtual world objective? You know, it’s like, I can’t read things in PDF format. I have to print things out because it’s not physically grounded as an object. To me it’s as ephemeral as thought. Before, we were talking about how information is proliferated, moving through space, virtually, between us. With my drawings, the shadows I’ve drawn are those immaterial non-objects but they ground the image. It’s an index, anchoring the drawing in a very specific space and time.

NY

When I read the text in your work, the way that you break up the text, like the word “and”…

Nyeema Morgan, horror horror V, silkscreen with digital print, 14.5 × 30 inches, 2022. Photo by Evan Jenkins. Courtesy of the artist and Patron Gallery.

NM

Yeah.

NY

Might be just the two letters, “a-n,” and “d” appears further down the line of text, where it doesn’t belong, so it forces you to read it fragmented, and to slow down. That slowing down of reading makes me aware of the text as an image and, simultaneously, I would still argue that it functions as language, so it’s doing both. What it communicates is important to the way that I read the work.

NM

Yes, and foremost, it makes you aware that you are engaged in a process, a cumbersome process of reading. The reader becomes more self-conscious because we doubt our ability to read. As I read it—an…oh wait, no—and then you go back.

That’s also very important, for me.

NY

Once I’ve read it, it departs from language. Then it comes back to language.

NM

Are you saying text and language are inseparable? I can read Hangul, but I only know the meaning of enough words to get by. Even so, occasionally I’ll see one of the few words I know but it is unfamiliar to me until I read it and then it’s, Oh, yes, “love.”

NY

Yes. And then there’s form, and you’re putting it together, back into language.

NM

With the understanding of it as form, as image.

Nyeema Morgan, Soft Power. Hard Margins. (1504), 2021, cast resin, acrylic, wood, LEDs, metal leaf, mixed paper media, 43 × 31 × 3 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Grant Wahlquist Gallery.

NY

Right. Maybe this heightens our understanding of text as part of the system as knowledge production. Because once you put together the text, and make sense of it, and it becomes language, and you understand that language is also a system of language production, specifically within the Soft Power. Hard Margins. series. What the text actually says is part of the system of understanding art, and is part of the system of knowledge production. How do you produce that kind of power, and access, to understanding art, producing art, participating in the discourse of art? In Soft Power. Hard Margins. the language is telling you about a way of producing, that the artist has essentially broken a rule of artistic production. In breaking that rule, you’ve expanded the rules of production.

NM

Well, when you say the rules of production, I don’t understand. Because if you’re talking about the text in Soft Power. Hard Margins., it’s more about ascertaining meaning from these works in the present moment. So, it’s about permission. The works communicating a certain kind of permissive authority. Right?

NY

That’s what I mean, yeah. When I say the rules of production, what I mean is like, you’re allowed to make art this way.

NM

Not even make, but you’re allowed to be, you know?

I’m thinking about the day that I wrote the text “Permission to be Masterful” in Soft Power. Hard Margins. I guess that’s what you’re talking about in terms of production. But then there’s like Johannes Vermeer’s Girl with the Pearl Earring, permission to idealize conventional beauty, which doesn’t have to do with production really.

NY

Well, I guess I mean that permission to make an artwork that idealizes conventional beauty, and the making of—I’m using the word production.

NM

Yeah, but you know what? The work of art doesn’t speak just to artists. The Mona Lisa is printed on mugs and T-shirts and screen printed on beach towels and all that stuff. Not because it’s giving this kind of permissive instruction on how to be an artist, but it’s woven into our system of beliefs and values beyond the art world. “Permission to be Masterful” speaks just as intensely to the surgeon to Tiger Woods to Marie Condo (laughter) as it does to the art student.

NY

This is true, but you don’t think it first gives permission to the art to be. Let’s just take that example: the “Permission to be Masterful.” That, to me, suggests the production of that artwork, the acceptance of that artwork, within the canon of artistic production. Once it’s accepted, now that’s an acceptable way to make. It’s also an acceptable way to be. In a more general, cultural sense, that’s not the way to make art. But we don’t need permission to be masterful now. That permission has already been given.

NM

I think we do. I think the beliefs that are instilled need constant reinforcement. You’re still thinking predominantly about art for art’s sake, existing in this hermetic art bubble. But now, [the statue of] David could be wearing Ray-Bans holding a Budweiser and communicate the same thing—“permission to be masterful”—which has a different connotation outside of art making about taste and consumption. Same permission, different social context.

Nyeema Morgan, Untitled, No. 1 (I, Rhinoceros), 2014, cast and painted resin with found objects, 18 × 8 × 49 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Grant Wahlquist Gallery.

NY

I forgot why I brought that up in the first place. Oh. Because whether it’s permission that’s given to the artist, or permission that’s given culturally, in a broader sense, and I agree with you. I think it’s both. That permission is part of a system of knowledge production. So, the language, if I understand the text as language, is always part of your revealing the way the knowledge production is produced. But I have to understand it as language in order to think about it when encountering the work.

NM

Yeah.

NY

As it moves toward an image or an object or a form, it makes me think about the system of language itself, and how knowledge is produced through that, so simultaneously, it comes back around full circle, starting with understanding language, which is a system, and then understanding the text as a form.

NM

Yeah.

NY

I have another question. I don’t know if this might be a departure, or it might tie into what we’re talking about now. Sometimes it doesn’t seem certain whether in your work, the subject is the politics of art inheritance, or if that’s a metaphor that points to other social structures.

In your work, is the subject the politics of artistic legacy or is it a metaphor that points to other social structures?

NM

It’s both. I’m an artist. I understand the world through the language of art—through aesthetics and material and ideas. Everything that happens within the art world— phenomenologically, discursively, politically, economically—is nestled within a larger culture, a larger system. So these things are related. So my work is never “this” or “that,” but a layering of considerations and propositions. My work, my sensibility as an artist, allows me to access a fuller understanding of the world.

NY

Yeah, yeah. Thinking about narrative and how it functions, the press release for your show, The Set-Up, mentioned the works coming together as a reflection on some important events in your personal life, as well as our shared lives: the death of your mother, the Trump presidency, and COVID. Also, both your kids were born in the last seven years. How did those personal events complicate the shared events that fueled your work?

NM

A lot has happened in the past several years. The intimate experience of being at my mother’s side as she died, having two young kids under six, then moving to Chicago, then COVID, and then, the cherry on top, the Trump presidency. I reached peak stress levels to the point where I was in an urgent medical crisis. As a Black person in America, I had sort of resigned myself to it because this was my mother’s fate, my grandparents. We live in a persistent state of trauma until we succumb to it. But I had to ask myself, Is there a way out from underneath this? Historically, are all the relationships and practices we’ve forged over the centuries enough to carry us through this ongoing mess? Is catharsis attainable for us now? For me? Can I release enough pressure to survive longer than what has been statistically prognosed for Black people in America?

NY

Right, right. I’m just curious because like, there is a way to be cathartic, individually, like personally, the purging of your own stress and anxiety. Maybe it is a cathartic pain. And then there’s a way that you’re talking about the work as an investigation of catharsis.

There’s a personal catharsis, the purging of your own stress and anxiety. Then there’s a collective catharsis you’re thinking about, right?

NM

The source of my own anxiety and trauma is highly personal but also rooted in our collective experience. We’ve cultivated traditions that have helped us mitigate our internalized trauma. Aesthetic traditions rooted in sound, music, movement, visual art which were rejected by mainstream culture before they became co-opted, monetized, and/or appropriated. That’s what led me down the path thinking about the relationship between art and catharsis and interpretation. During the pandemic, I was watching the Dave Chappelle interview with David Letterman. Did you watch that?

NY

For a while.

Nyeema Morgan, A priest, a rabbi and a minister walk into a bar. (The Set-Up) (detail), 2022, wood, resin, lacquer, paper media, tools, 47.25 × 24.75 × 18.25 inches. Photo by Evan Jenkins. Courtesy of the artist and Patron Gallery.

NM

I was really excited to watch it because I wanted to know, What was that moment that precipitated him leaving his show at the height of his popularity? I was really excited about the refusal, and it lingered with me as an important act. At the time, we didn’t know anything. The decision was abrupt, and it seemed like something happened. So during this interview, he spoke about it.

NY

What happened?

NM

He was rehearsing a sketch where there was a Black protagonist, and every time that character did a specific thing, Chappelle came out dressed as a pickaninny or some classic racist characterization and he did this hyperexaggerated gesture or dance. He said as they were rehearsing it, some of the white crew members were laughing too hard whenever he came out as the racist character. He said it was just the wrong kind of laughter.

NY

That reminds me of your talk with Mike, the other day, when he asked you if there’s a wrong kind of beauty. Like, what’s the wrong kind of laughter?

NM

Yes! Well, I imagine he thought it was a misinterpretation of his brand of comedic social critique. Based on the description of the sketch, I imagine it was a satirical expression about racial judgment, angst, or shame. Or the sketch about the Black Klansman who’s blind and doesn’t know he’s Black. We can laugh at the irony but also cringe and feel the weight and sadness of self-hatred.