In the soil, in the sound: Houston’s Jamal Cyrus gets to the root of Southern Black aesthetics

Scalawage / Nov 17, 2022 / by Alysia Nicole Harris / Go to Original

Jamal Cyrus at the Mississippi Museum of Art gestures to collaged album covers from his installation series about Pride Records, a semi-fictional Black record label. Photo by Ron Blaylock. Image courtesy of the Mississippi Museum of Art.

“I feel like within Black aesthetics, you know—especially, music—there’s just a certain kind of vitality that cannot be denied…”

Jamal Cyrus

When Houston-based artist Jamal Cyrus says he’s interested in experimenting with the fundamental principles of the Black aesthetic, I pause the YouTube recording. It’s a task that, on hearing, sounds intriguing, but maybe a bit impossible.

Besides, I’m not sure there is something particularly unique to be discovered, or that there’s a monolithic Black aesthetic, only one way of doing Blackness, there being so many ways of being Black. But a part of me stirs with mischievous hope.

Suppose it could be done, and we could get down our commitments—not to outcome, but to overcoming, to process: What would those resulting Black visual expressions look like? What new epiphanies arise by moving as Blackness moves?

Toni Morrison set after answering the same questions within prose, saying of her work in her essay “The Writer Before the Page,” “I simply wanted to write literature that was irrevocably, indisputably Black, not because its characters were, or because I was, but because it took as its creative task and sought as its credentials those recognized and verifiable principles of Black art.”

Remembering the revelation that was reading Morrison’s Sula for the first time, I press play and allow Cyrus’ talk to continue.

Jamal Cyrus (b. 1973), The End of My Beginning, 2005. Image by Allyson Huntsman, courtesy of the artist and Inman Gallery, Houston. The installation features thick mounds and rolling waves of bristly black hair that blanket an otherwise genteel suburban setting in this sculpture maquette. Small trainset figurines and a white clapboard house are enveloped in a blizzard resembling an Afro. Cyrus employs what he considers an eminently “Black” material to suggest—and arguably announce—the arrival of a new dawn.

Jamal Cyrus’ newest exhibition, “The End of My Beginning,” opened October 29 at the Mississippi Museum of Art, following its debut in Houston at The Blaffer and a tour at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles earlier this year. The show highlights 15 years of working with and through the histories and melodies of Black radical expression. In sculpture, installation, mixed-media, assemblage, and collage, the diversity of Cyrus’ practice is on full display.

I find the mixed-media and textile collage works some of the most fascinating. At its most basic level, the practice of collage is about taking materials—paper, photographs, fabric, etc.—from disparate sources and bringing them together toward a novel end.

For Cyrus, this method of making has deep connections to principles of Black cultural production. Whether it shows up in the generational practice of piecing used rags and work clothes together to form abstract quilts, or in hip hop, where producers sample melodies with intergenerational history in order to make sounds with memory—collage is one of those recognizable principles of Black art.

Cyrus speculates that our propensity for piecing originates from a history of being under-resourced; at the heart of making do is making, which, by nature, is a creative act.

“I would say that within Black American art, I think it starts with resources, but then a creative sensibility starts to develop over time,” said Cyrus during a phone interview earlier this summer. “I think [collage is] a technique that, because of our experience, we’ve become very adept at.”

The practice of collaging gains three-dimensionality in Cyrus’ assemblages, which differ from traditional sculptures in marble or bronze in that they are composed of found objects rearranged and re-imagined. These become some of the artist’s most intimate and visceral works.

Pillowy masses of Black hair engulf a miniature dollhouse in the show’s title work, The End of My Beginning (2005). A plush afro carpets the lawn, the roof, the roads of this white suburban world. The hair invokes a naturalizing, harmonic force able to reclaim such a sterile and curated space even as residents are swallowed by this ever-encroaching swath of Blackness. It’s an image of a white fantasy apocalyptically eclipsed. The work is insurgent.

The word radical comes from the Latin word for root, and that’s what we see in The End of My Beginning: natural Black hair growing full and deep, Blackness expanding beyond its specified environment, Blackness taking root.

Radicality shows up in Cyrus’ practice twice over, as both subject matter and methodology. Visual abstraction is his means of getting to the root of what’s at stake. For Cyrus, that’s the patterns, artifacts, and self-determined strategies that shape and construct Black experiences.

In his Focus exhibition at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth in 2022, Cyrus explores the geography of the Trinity River Basin and its relationship to free jazz. Left: Blue Alluvial Glue 2 (Line), 2022. Middle: Horn Beam Effigy, 2022. Right: Blue Alluvial Glue (Shape), 2022. Photo by Kevin Todora. Image courtesy of The Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth.

Abstraction is seen by many as another pillar of Black aesthetics. Black abstractionists in the U.S. from as early-mid 20th century forewent focusing on the visual representation of Black bodies—the center of so much distracting controversy and consternation—either to surface the political and geographic constraints operating on us, or operate in creative freedom outside them.

The invention of race is itself a gross abstraction, one which arose as a way to strip away from Black people our essential personhood. But in the hands of artists like Cyrus, abstraction becomes a strategy for restored sight. Nowhere is this rendered more acutely than in his series of two-dimensional works dealing with government surveillance of Black radical figures.

“The End of My Beginning” features denim collage paintings and graphite paperworks that Cyrus creates from stencils of redacted FBI files on Malcom X, author Richard Wright, singer Marian Anderson, and actor and activist Paul Robeson. In Cultr_Ops in Blue (2020), he glues thin strips of faded and acid-washed denim together in a form reminiscent of ruled paper, with darker denim strips over top to create thick irregular blocks. Without the title, perhaps you’d think it was a subtle investigation of cotton and denim as a material; you’d never guess it was spelling out lines of redacted text.

Despite the indecipherability of the source, Cultr_Ops (2008/2015) makes legible both the ongoing practices of racialized terror and the tactics used to obscure that same history. Cyrus’ minimalist works become artifacts of the ongoing patterns of violence that jumble our histories but they also document the ways we intervene.

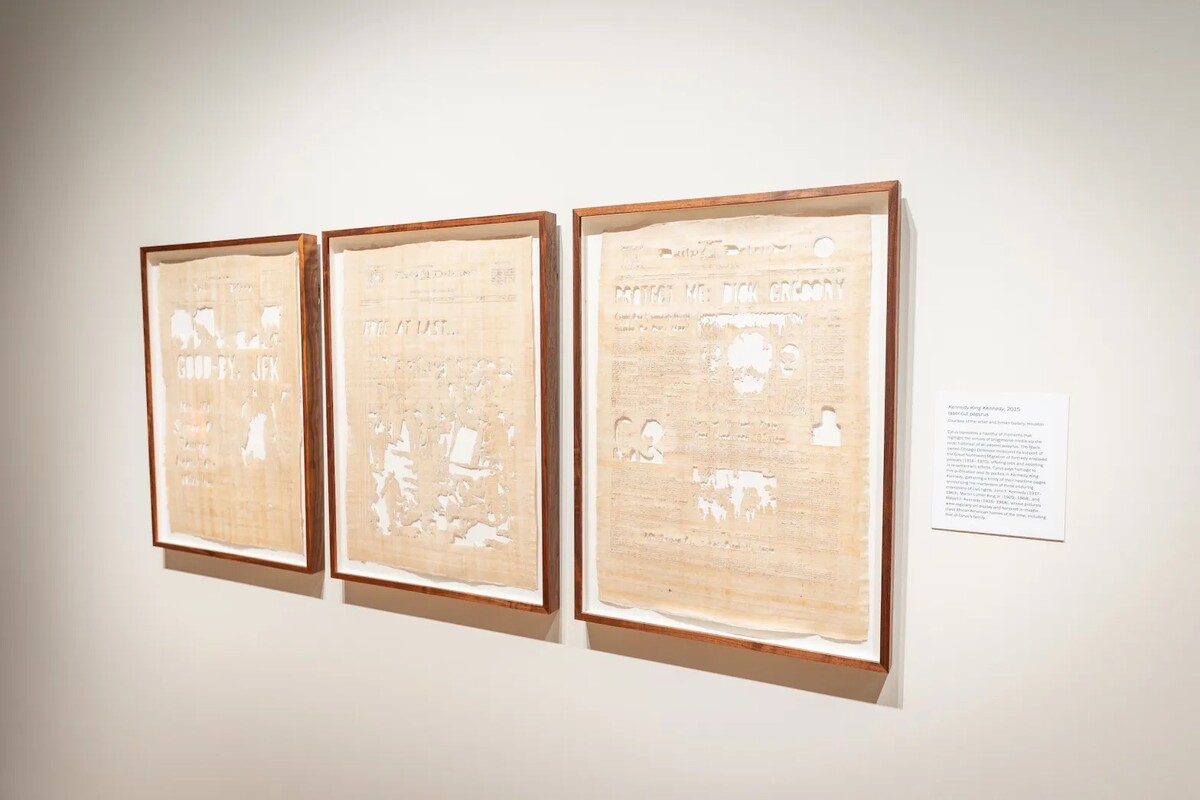

Kennedy, King, Kennedy, 2015. This triptych of laser-cut papyrus is inspired by the mantel altars to John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert Kennedy found in many Black households and mournfully documents the assignation of celebrated leaders. Photo by Ron Blaylock. Image courtesy of the Mississippi Museum of Art.

Consider Eroding Witness 7 (2014), a series of papyrus scrolls laser-cut with four different local newspaper accounts—two Black and two white—of the 1970 police assassination of Carl Hampton, a local community organizer in Houston’s Third Ward. As Steven Matijico notes in his essay for the artist’s monograph, the ghosts of words like “police fired first” and “who helped police set up Carl Hampton” reveal how mournfully Black newspapers decried Hampton’s murder as an instance of police terror, while the Houston Post relegates it to a footnote, refusing to announce it on the front page.

And yet, when looking at Cultr_Ops, I’m reminded that despite the surveillance and erasure that made our stories illegible, even to us, we still made art. Masters of reading between the lines, Black folks don’t just imagine who and what’s missing. When the archive erases our leaders and loved ones, we boldly place them back inside the story.

In utilizing political narratives and cultural artifacts manufactured by the state to police Black creative production and snuff out any radical elements, Cyrus, in a sense, subjects his process to the same constraints as Hampton, Wright, Garvey, and Black folks living in the U.S. today. He’s an artist of Black aesthetics not because he’s painting Black figures, but because he’s making Black choices.

Cyrus’ career has quickened over the last several years, beginning with his receipt of the High Museum’s prestigious Driskell Prize in 2020. “The End of My Beginning” marks the artist’s first institutional career survey, displaying over 50 works spanning from 2005 until the present.

Jamal Cyrus was born in 1973 to a family of Southern musicians, chefs, and artists. His focus on visual arts began in childhood but was honed while a student at Texas Southern University, where he now teaches. At TSU, the teachings and legacy of the school’s art department founder, John Biggers, had a deep impact on Cyrus. Biggers encouraged his students’ interest and exploration of radical ideologies that bucked institutional norms.

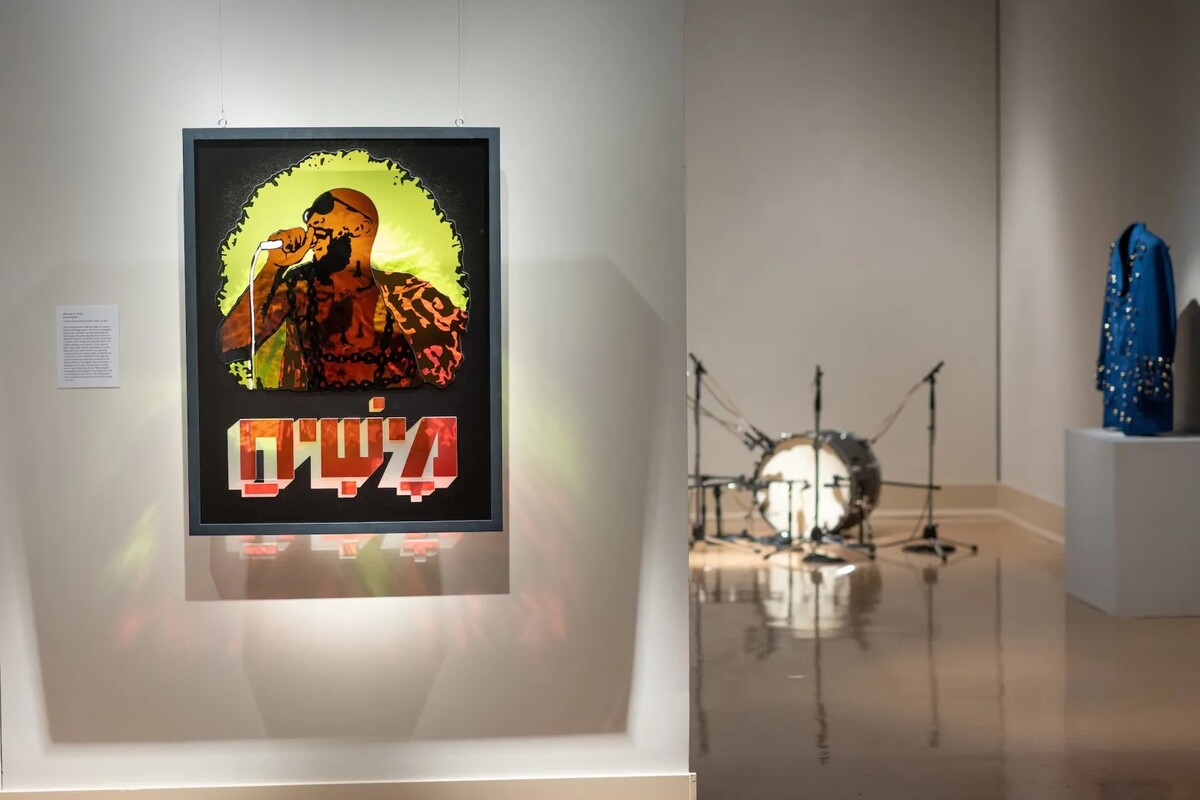

Installation view of Meshiak III, 2021. Photo by Ron Blaylock. Image Courtesy of the Mississippi Museum of Art.

In 2002, Cyrus and former classmates Jabari Anderson, Kenya Evans, and Robert Pruitt founded the art collective Otabenga Jones & Associates, whose mission statement was as follows: “To teach the truth to young Black youth, to extend the parameters of the trans-Atlantic Afro-diasporic aesthetic, and to mess with whitey.”

This third principle is exemplified by the protests Cyrus and Pruitt staged outside of the Museum of Fine Arts Houston to protest “African Art Now,” a 2005 exhibition of contemporary works from 28 artists representing an array of African countries. The collection was poorly contextualized, the two charged, and lacked rigorous understanding of the traditions that many of the African artists were working in and against. According to Ana Tuazon’s article “The Space Between Then and Now: Otabenga Jones & Associates (& the 10,000 Various Members Big & Small),” the works were sourced from the collection of Jean Pigozzi, a Swiss man who had never even visited the continent before.

While Cyrus’ work continues to challenge the institutional record of Black cultural production and dissemination, the artist is now exhibiting at museums and galleries similar to those he previously critiqued. Last year Chicago’s Patron Gallery held Cyrus’ his first major solo exhibition outside of his home state, titled “Manna and Braised Collards.” Showcasing sandbagged pew benches, stained glass emcees, and muraled lyrics from spirituals, the show pulled from spirituality, food, and music, communal traditions that ground Black southern identity and have long functioned as covert forms of resistance.

Although the inspirations to Cyrus’ work are many, his fascination with Black vernacular music cannot be overstated. Sculptures like Untitled (Grand Verbalizer What Time Is it?) (2010), Texas Fried Tenor (2012), and Horn Beam Effigy (2022) feature instruments disassembled, fractured, cut in half, fried, or turned upside down. These are remixes, new ways of looking at the form and function of these harbingers of culture.

I saw Horn Beam Effigy in person in June of this year as a part of Cyrus’ Focus exhibition at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, in which he continued his investigation into the South’s “sonic territories.” Sonic territory refers to a geographically and musically fertile area around waterways that benefited from the movement of peoples, cultures, and innovation. New Orleans is one such geography, giving rise to the drum kit and the syncopated rhythms of Dixieland jazz. The Mississippi Delta, with the blues, is another.

For his solo show at the Modern, Cyrus took as inspiration the work of jazz saxophonist and composer Julius Hemphill and other free jazz musicians of the 1970s coming out of Dallas-Fort Worth and the surrounding Trinity River Basin. Musically abstract, these artists broke with the established tempos and rhythms of Dixieland, big band, and bebop tradition.

Entering the exhibition, I was perplexed at the amount of restraint: a restricted color palette in black, off-white, and a working man’s blue. It was only when I looked closer that I realized more was going on. Laminose cotton threads make abstract patterns. The striated fabric invokes layers of sediment pressed down, layers of cultural and sonic sediment that accrete over time to shape and structure the flow of new sounds through the region. The blue darting across Blue Alluvial Glue 2 (Line) (2022) suggests a river, a current, things in flux.

Common Tongue, 2022. Photograph by Kevin Todora. Image Courtesy of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth.

In Common Tongue (2022) and Blue Alluvial Glue 3 (2022), the textile collages picked up musical alluvium. Bits of vinyl records and the ebony of black piano keys embedded in the textiles suggest that music innovations do not just result from the landscape; they become a part of it, a part of our cultural inheritance.

In an interview for the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth earlier this year, Cyrus remarked on how music can be used to transcend everyday experiences, to connect one’s personal identity to a larger cultural tradition, and as a fertile soil where history is stored and seeded:

I think that’s one of the reasons why, when you talk about visual artists or writers or whatever, the wellspring has been Black music. And that’s kind of what I take up on as well, and it’s not necessarily trying to represent what happens in the music. It is trying to create something that leaks into that territory, that uses that sensibility.

Articulating for us a Black aesthetics, Cyrus also ends up formulating a component of what a broader Southern aesthetic might be. He helps us recover a sense of radicality which is often denied our region.

The history of Southern Black politics is often eschewed as long-suffering, and even docile—rarely demonstrating the radical break with whiteness associated with Black Power movements in other regions of the U.S. But Southern radical practice, Cyrus suggests, can be found most deeply in the music.

“Within Houston, I feel like I grew up in a very, like, culturally dynamic environment. But in terms of those types of politics, they were not,” noted Cyrus. “They were expressed in other ways, but they were not overtly expressed in terms of organizing within my family and the people who I was connected to. And so it wasn’t until I started to be exposed to [radical politics]. Once I did, once I started to dig into that eventually I began to uncover aspects of that happening in Houston, that was happening in Texas.”

The artist in front of his installation Pride Records findings—Tokyo, 2005-16. Photo by Ron Blaylock. Image courtesy of the Mississippi Museum of Art.

Music—more than any book—is our record of cultural and interpersonal storytelling.

Abstract, expressive, vibrating with an inquisitiveness and real-world conviction that pushed against the received understanding of how it should sound or how it should look, musicians of the free jazz movement took the basic building blocks of instrumentation and built a sound in their image.

Music, like a river, carries political and social ideas across our region and the world. These ruptures with the forms of the past then get transposed, repurposed, and remixed.

“Abstraction—and music—it’s the place for me where I can play with [Black aesthetic principles]. And by play, I mean, set up processes in which I’m borrowing from those principles, but I’m also learning from the process,” said Cyrus.

The more I study his career, the more I understand: Cyrus is creating a visual archive of our past and present movements through the world, up a scale, undercover, and over the waves. In so doing, Cyrus makes waves of his own.

Works like Blue Alluvial Glue 2 (Line) collaborate with the redacted works of Cultr_Ops in Blue on display in “The End of My Beginning.” Through layers of soil, history, notations, codes illegible and legible at turns—some rendered by the hands of the state, others by the hands of the river, and others by the hands of our musical geniuses—what emerges is a materiality of Blackness that links us to blues. Not just blues music, but the blue siren light of constant police surveillance, the wide blue rupture of the Atlantic, and the brackish traffic of all waterways which lead back to that source.

Through our blues, a body of aesthetics takes shape. And that body is Black.