Is Abstract Expressionism back?

Art Basel / Nov 1, 2022 / by Nicholas Nauman / Go to Original

For all the transformations and innovations that art has undergone in the long evolution of the modern world, painting repeatedly announces itself as a crucial, ever-inviting medium. Its developments have yielded countless experiments that have challenged the very notion of what makes a painting. Among the watershed turns in the history of the art form, few have burrowed into the popular imagination as irrevocably as Abstract Expressionism. From Jackson Pollock’s splatters to Helen Frankenthaler’s smears, from Cy Twombly’s squiggles to Mark Rothko’s blocks of color, the canonical Abstract Expressionist artists eschewed representation to foreground the intense affective capabilities of color, shape, and the material of painting itself.

Today, a growing number of younger painters have adopted many Abstract Expressionist techniques and modes of exploration to move the tradition away from its now-conventional, male-dominated past into a vivid present. These artists mark a notable shift from last decade’s trends in abstraction, which tended to prioritize pleasing the market and resulted in the aesthetic often referred to as ‘Zombie Formalism.’ With enlivened practices of rigorous craft and deeply felt personal stakes, the following artists – all of whom are showing at Art Basel Miami Beach this year – exemplify what we might call Neo-Abstract Expressionism.

Marley Freeman, Care in the open, 2020. © Marley Freeman. Courtesy of the artist and Karma, New York City.

Marley Freeman (b. 1981, Massachusetts, USA) paints with a fascination for the physical reality of the pigments she uses. Her canvases are crowded lumps and strips of color that tease each other’s edges in small moments of playful tension. god’s own head (2021) centers on lopsided cherry-red arches, which are echoed in salmon and green, and filled in with chunks of blue and curves of black. The occasional drip of paint runs through discrete areas of color, as in Consecutive Nights (2021). This painting also features another of Freeman’s favorite tactics, wherein an underlayer peeks through a thin overstroke: here a vibrant cerulean beneath muddy green.

Freeman often works small, creating compact statements that stage a coinciding of methodical precision and unselfconscious wonder, on full display in pieces such as the spottily textured Care in the open (2020) or Each-Other (2020), which is teeming with relaxed, sky-blue whirls and dollops of streaky vermilion. Freeman’s works recall the paragon outsider-insider artist, Forrest Bess, as well as artists far from the pantheon of American abstraction, like the Dutch painter Bram van Velde, or the so-called CoBrA (Copenhagen, Brussels, Amsterdam) artists of the 1940s, like Erling Jorgensen. Freeman is a painter of pointed intention whose practice evinces as much discipline as whimsy.

Marley Freeman, Each-Other, 2020. © Marley Freeman. Courtesy of the artist and Karma.

Marley Freeman, earth anew, 2021. © Marley Freeman. Courtesy of the artist and Karma.

Rachel Jones (b. 1991, London, UK) has made a serious impression in recent years with transfixing works featuring energetic traces of scraping, rubbing, and deliberate gesture. According to the gallery, Jones engages what she calls an ‘exegesis of color’: she covers the canvas with thick, emphatically rendered patches of oil stick and pastel, scattered with brisk lines and blurred collisions to illustrate her interior world. Paintings such as SMIIILLLLEEEE (2021), in which a central pair of overlapping circles is surrounded by sections of bright yellow, orange, and mahogany, cut through with fastidious scribbles, bring to mind maps of ever-evolving territories.

Rachel Jones, SMIIILLLLEEEE, 2021. © Rachel Jones. Courtesy of Thaddaeus Ropac. Photo by Eva Herzog.

Rachel Jones, say cheeeeese, 2022. © Rachel Jones. Courtesy of Thaddaeus Ropac. Photo by Eva Herzog.

Another work, also called SMIIILLLLEEEE (2021), is blasted even more thoroughly with vigorous angles and ecstatic shades of purple, green, and sizzling red. As the common titles indicate (those are but two of many distinct SMIIILLLLEEEEs, while numerous other paintings share names, as well), Jones is interested not only in the effects of repetition in general but, especially, in the motifs of mouths and teeth – those disorderly forms that move at the threshold of a body’s inside and outside. In A Slow Teething (2020), the sections dappled with reds, greens, and browns conjure teeth in a state between rot and becoming; in one of several works titled say cheeeeese (2021), the canvas is completely overtaken by frenetic yellow and licks of purple. Hardly arbitrary, such repetitions and references to the body are crucial to communicating Jones’s non-normative experience of herself in the kinship of Black community.

Kaveri Raina (b. 1990, New Delhi, India) uses materials like acrylic, oil pastel, and graphite on burlap canvases, employing their textures and porous surfaces to create paintings that strike an uncanny balance between physicality and ethereality. Dark fields of earthen hues – ochre, forest green, rich browns – activate her canvases, alternately cramping and expansive. The resulting tension is beautifully sublimated in paintings like To Perceive Is to Suffer; Revisited (2021–2022), in which a yellow sphere, irregular and split by softly jagged browns, appears to slump like a head and lift like a balloon at the same time. Revolt; Internal Brewing Slow Rage (2021) arranges green and goldenrod angles across a dim pink ground, enrobed throughout with swirls of graphite.

The Chicago-based artist Carmen Neely (b. 1987, North Carolina, USA) works with a vocabulary of calligraphic bursts and swipes of color. In her oil paintings, which are often laced with graphite, intense aggregations of gesticulated line gather and stray across creamy backgrounds that have too much body to be called negative space. In Without the dramatics of surgical procedure (2021), slashes of cool blue and white are woven with browns to make a pyramidal form that pushes up the canvas like an icy bonfire.

Carmen Neely, Without the dramatics of surgical procedure, 2021. Courtesy of Mariane Ibrahim.

In To lean could be to fall (2022), bodily browns stretch to the edges of the frame and invite a sense of simultaneous risk and release. Maybe it’s about untangling some of that (2021) splits its horizontal orientation into two distinct sections that nonetheless involve each other with overlapping, sporadic green and beige and blue. That piece also includes small but decidedly legible letters that spell ‘OK’ – a word that belies its simplicity in proximity to Neely’s brushstrokes. It serves as a reminder that her marks and flurries are striking assertions of the meaning just beyond the edge of legible forms.

Carmen Neely, Maybe it’s about untangling some of that, 2021. Courtesy of Mariane Ibrahim.

Carmen Neely, To lean could be to fall, 2022. Courtesy of Mariane Ibrahim.

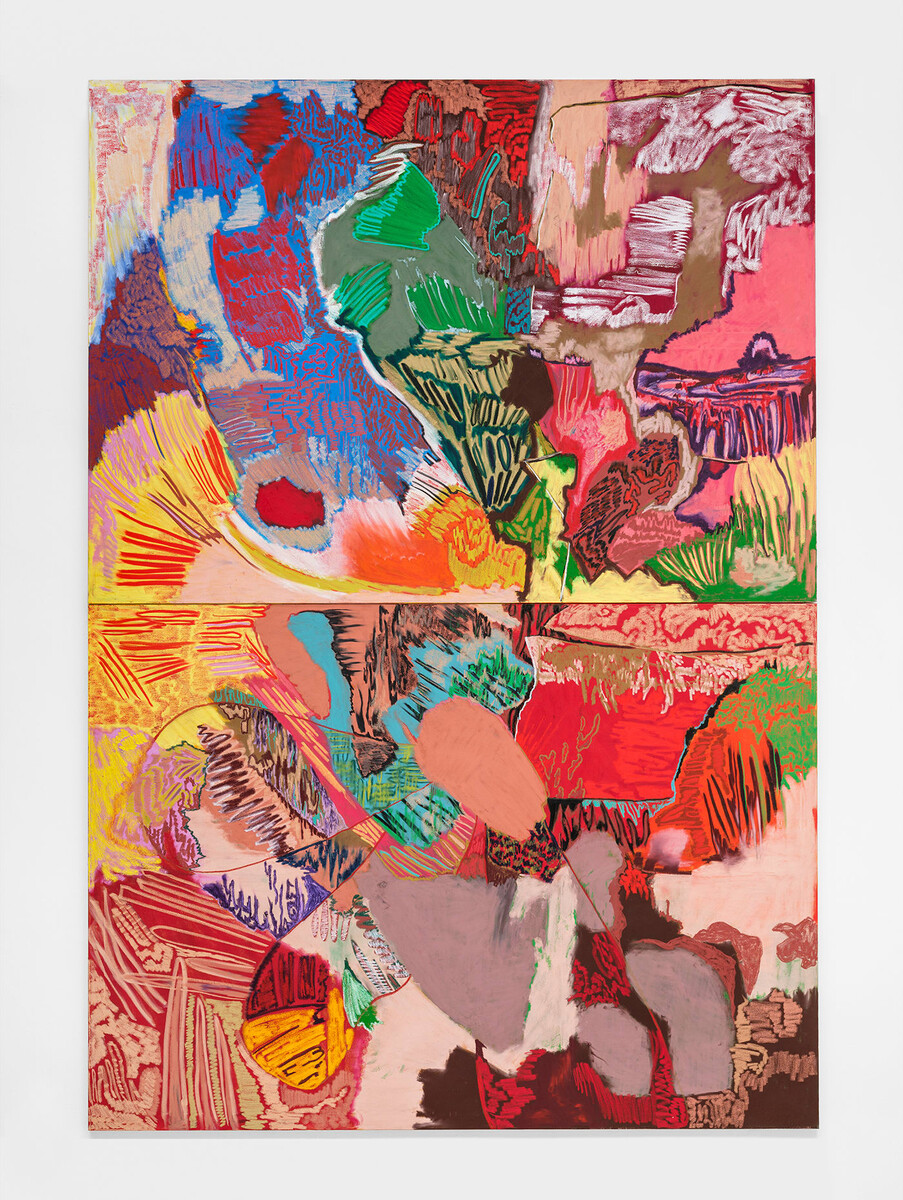

The broad canvases of Michaela Yearwood-Dan (b. 1994, London, UK) are brimming with vibrancy and materiality that make affective power out of unrestrained color and form. She draws inspiration from a well of cultural and personal influences: the various exultations and sufferings of Blackness, queer community-building, a British Catholic upbringing, and a sense of humor that led her to hold serious philosophical discussions with Apple’s ‘virtual assistant’, Siri. All these aspects play out across pieces like A conduit for joy (2021), a double-paneled painting in which swathes of rose and crimson surround aqueous blues and patches of inky darkness, overlaid with leaf-shaped greens and a central, highly legible bit of text that asks, ‘How does it get even better?’ Like Neely’s ‘OK’, Yearwood-Dan’s inclusion of hand-painted words recalls and reconfigures such classic precedents as Robert Motherwell’s ‘Je t’aime’ series.

Left: Michaela Yearwood-Dan, Beyond the veil of the mythical super woman, 2021. Right: Michaela Yearwood-Dan, Don’t forget it, 2021. © Michaela Yearwood-Dan. Courtesy the artist, Marianne Boesky Gallery, and Tiwani Contemporary, London. Photo credit: Lance Brewer

In a welcome pivot from the market-governed conformism that defined so much abstract painting in recent years, these artists usher in a welcome era of scrupulous method and palpable feeling. A term like ‘Neo-Abstract Expressionism’ may describe some formal commonalities of such an array of painters but, more importantly, it hints at the vitality that motivates their diverse approaches to the medium. The potency of their artworks is a clear affirmation of the ongoing ingenuity of their form, perfectly in line with tradition and absolutely on their own terms.

From left to right: Marley Freeman. Photo by Sarah Rice, The New York Times. Rachel Jones, 2021. Photo: Adama Jalloh. © the artist. Courtesy of Thaddaeus Ropac. Kaveri Raina. Courtesy of the artist and Patron. Photo by Zhiyuan Yang. Carmen Neely, 2022. Courtesy of Mariane Ibrahim. Michaela Yearwood Dan. Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Kristy Noble.