How Chicago Became an Art-World Capital Without Giving In to Art-World Clichés

Harper’s Bazaar / Dec 11, 2022 / by Stephen Mooallem / Go to Original

PHOTOGRAPHS BY JOHN EDMONDS; STYLING BY ALEXANDRA DELIFER

Theaster Gates in his South Side studio with A Game of My Own (2017). Shirt, Maison Margiela. Jeans, Prada. Boots, his own.; JOHN EDMONDS

Theaster Gates has been thinking about monuments. “Young Lords and Their Traces,” his new survey at New York’s New Museum, is all about the way objects carry memories. It’s a familiar theme in Gates’s work, which often highlights the labor, craft, and life in reclaimed materials. The recent losses of some people who were important to him in different ways—like Gates’s former organ teacher and friend Alvin’s mother, Christine Carter, and his longtime colleague at the University of Chicago professor Robert Bird—were weighing on him. So Gates decided to turn the entire show—a collection of sculptures, clay vessels, paintings, repurposed items, and mixed-media works—into a memorial. In tribute to Carter, an organ is the focal point of an entire gallery, flanked on either side by works made from floorboards taken from New York’s Park Avenue Armory. Bird’s expansive library of books on film, art, Russian literature, modernism, and media theory is neatly arranged on a set of shelves in the middle of another. There are tar paintings inspired by the craft and discipline of Gates’s late father, Theaster Gates Sr., who was a roofer, as well as the items and works of other artists, like a boot that belonged to the painter Sam Gilliam and a pair of sneakers from Virgil Abloh.

The personal dimension of “Young Lords and Their Traces” is a reflection of many facets of Gates’s life in Chicago, where he was born and raised and continues to make his home and work. But in many ways it’s less about losses than gains—how ideas, practices, friendships, relationships, and passions endure and are kept alive. “I used to think that monuments were about statues of old guys,” Gates explains. “But when I was doing my master’s thesis, I wrote about a synagogue on the West Side of Chicago that had been transformed into a Baptist church, a flea market, and a synagogue again over 80 years. The synagogue is a monument. It is a testament to the truth of many accumulated lives.”

Mariane Ibrahim in the office of her Chicago gallery with Patrick Eugène’s Seasons Change (2021). Bar jacket, blouse, and pants, Dior. Ring, Cartier.; JOHN EDMONDS

Gates may well have been describing Chicago itself, a city with an extraordinarily rich cultural heritage. Chicago was home to a mid-20th-century literary renaissance; an incubator for blues, jazz, and house music; the land of Archibald Motley and Richard Wright, of Lorraine Hansberry and Gwendolyn Brooks. It was the birthplace of modern sociology and advertising, a locus of the Great Migration. It is a city that was razed by a fire and rebuilt as a forest of skyscrapers. It is also one that has been shaped by decades of segregation and systemic racism, which were not just the results of public policy, urban planning, and discriminatory real estate practices but the very aim of them. As Mies van der Rohes rose in Lakeview and Lincoln Park, neighborhoods on the South and West Sides were decimated by poverty, crumbling infrastructure, school closures, violence, and the exploitation and willful neglect of developers and public officials.

Some, though, like “A Raisin in the Sun” playwright Hansberry and poet and educator Brooks, believed that artists could help transform those communities because they were a part of them. It was a notion also held by the writer and activist Margaret Taylor Burroughs, who in 1940 helped establish the South Side Community Art Center as a space for Black artists to create and commune. Taylor Burroughs and her husband Charles Burroughs held salons in their Bronzeville home. In 1961, they founded the DuSable Museum (then the Ebony Museum) in their living room. She also taught public school and lobbied for prison reform.

Nick Cave in his Irving Park studio with one of his Soundsuits. Clothing and boots, his own.; JOHN EDMONDS

More than two decades later, in 1986, another former public-school teacher, Isobel Neal, opened the Isobel Neal Gallery in River North, championing artists of color such as Phoebe Beasley, William Carter, Elizabeth Catlett, Ed Clark, Norman Lewis, and Charles White, all of whom had previously struggled to get their work shown. Neal and her husband, Earl, an attorney, lived on the South Side and were avid collectors; it was a passion they first began to feed by buying pieces at the local 57th Street Art Fair in Hyde Park. Neal decided to start her own gallery after chairing a juried exhibition on Black creativity at the Museum of Science and Industry and discovering that it was one of the few that did—and then, for the most part, during Black History Month in February.

The Isobel Neal Gallery provided a crucial outlet for these artists and helped cultivate a network for collectors for their work throughout the Midwest. “I was really shocked at the response,” says Neal, who ran the gallery until 1996. “People came out in droves, and I got a lot of press and media attention for showing work by African American artists for the first time. I really think that it was an awakening in the art world.” Nevertheless, the Neals still had to self-fund the gallery for the entire decade it was in business. “It wasn’t a money-making proposition,” Isobel explains. “It was a service and a mission.”

Gates, who grew up in East Garfield Park, bought his first building on the South Side in 2006 on Dorchester Avenue—a former candy store he purchased with a loan and a subprime mortgage. Since then, he has used his own increasing stature as an artist to revitalize the area, undertaking projects through his Rebuild Foundation like the Stony Island Arts Bank, an exhibition and performance venue housed in a neoclassical structure that was abandoned for 30 years and now houses an archive of “Jet” and “Ebony” magazines and the legendary house DJ Frankie Knuckles’s record collection. Gates recalls going to the South Side Community Art Center as a young ceramicist in the early 1990s: “I remember cleaning the basement, setting up a potter’s wheel, and wanting to continue to bring energy to that space.”

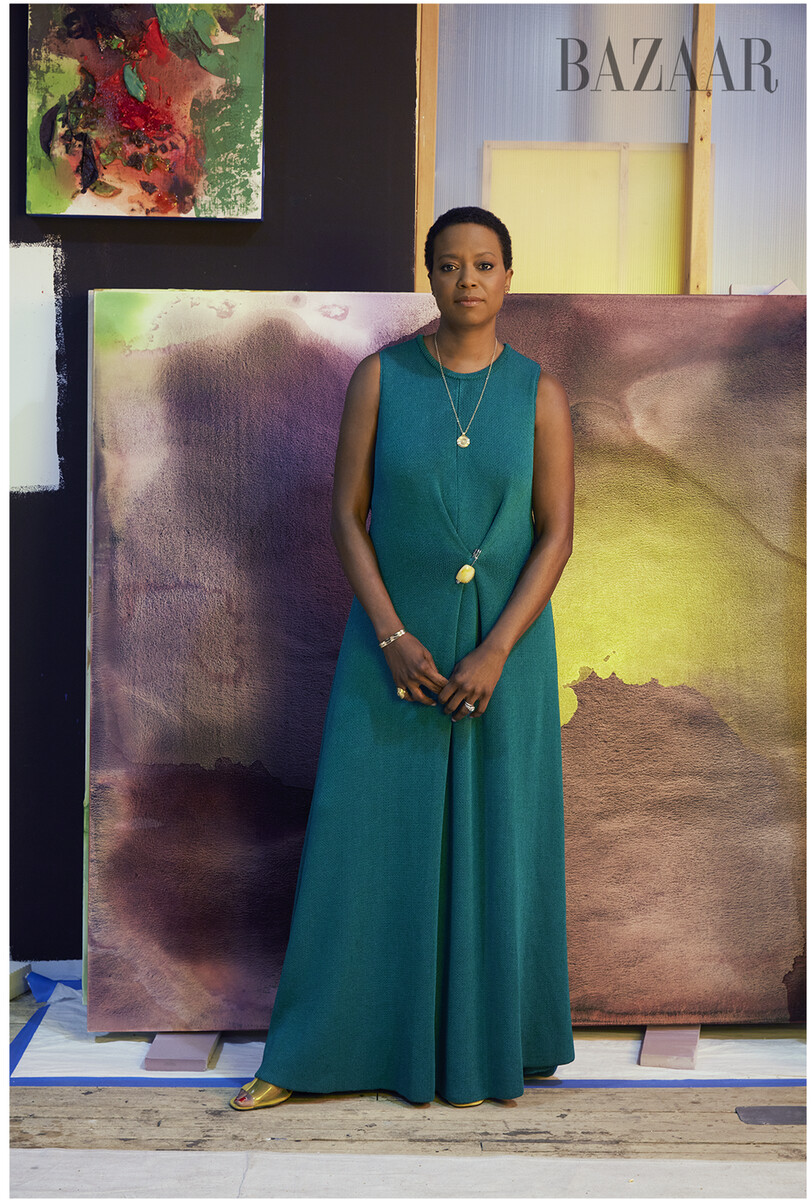

Amanda Williams in her studio. Dress, Proenza Schouler. Ear climbers, medallion, cuffs, and ring, Almasika.; JOHN EDMOND

If there is a great creative tradition in Chicago, it is in that unerring sense of potential and place. It’s in the work today of artists like Gates and Nick Cave, who have cultivated practices and studios that have become part of the fabric of the neighborhoods that surround them. It’s in the plethora of public-art projects that fill the city, like Kerry James Marshall’s mural at the Chicago Cultural Center honoring 20 women who helped shape Chicago’s creative landscape. It’s in the constellation of venues to see and exhibit art, which is now vast and varied: from mainstays like Gray, Kavi Gupta, and Rhona Hoffman; to independents like Mariane Ibrahim, Monique Meloche, Patron, Document, Regards, Volume, Corbett vs. Dempsey, Stephen Daiter, and FLXST Contemporary; to nonprofits like 3Arts, Art on theMART Foundation, Chicago Artists Coalition, ThreeWalls, Woman Made Gallery, the Arts Club of Chicago, and the Hyde Park Art Center; to artist-run spaces like Prairie. And it’s in Jackson Park, on the South Side, where the Obama Presidential Center broke ground in 2021 not far from where Michelle Obama spent her formative years and former president Barack Obama got his start as an organizer. The complex will include a museum, numerous parks, and a branch of the Chicago Public Library, with a sculpture by local luminary Richard Hunt near the entrance, the first of six planned art commissions to be installed throughout the campus.

Even Chicago’s world-class museums, like the Art Institute of Chicago and the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, manage to feel intimate and local, with robust slates of public programming and shows that reflect the changing face of the city, which has a growing Latin population. Among them: “Forecast Form,” a new exhibition at MCA Chicago that explores the art of the Caribbean diaspora. The show’s curator, MCA Chicago’s Carla Acevedo-Yates, was born and raised in Puerto Rico. She first began to formulate the concept for the show in aftermath of Hurricane Maria in 2017, when she and so many others of Puerto Rican descent in the mainland U.S. watched the devastation unfold in the region from afar as their friends and families on the island struggled to survive, many without food, power, or shelter. “The Puerto Rican diaspora in Chicago was one of the first communities that mobilized to help,” Acevedo-Yates says. “I believe that museums like MCA Chicago have a responsibility to not only reflect these experiences in their programming but actively engage with these communities.”

Candida Alvarez at Monique Meloche gallery with Are you listening to this? (2022). Dress, Simone Rocha. Earrings, Ten Thousand Things.; JOHN EDMONDS

What’s happening in Chicago isn’t a scene. It’s also not being by driven by brazen youths storming ungentrified territory to enact some mythological version of bohemia or the art market, which continues to maintain its pieds-à-terre in New York and Los Angeles. But it is, in many ways, a series of success stories.

In 2015, Emanuel Aguilar and Julia Fischbach, who had worked together at Kavi Gupta, scraped together their savings to start their own gallery, Patron, as a showcase for emerging and mid-career artists,. Their roster now includes Jennie C. Jones, who had a solo show last year at the Guggenheim in New York, and Bethany Collins, whose multidisciplinary works explore the connections between race and language. After leaving Kavi Gupta, they each contemplated moving away to pursue jobs at international mega-galleries in the traditional art-world capitals. But the desire to build a gallery of their own from the ground up, where they could work closely with artists, not just as dealers but as facilitators and collaborators, won out. “We’re from Chicago, so there was this deep desire to be a part of something here,” says Fischbach. “We want to make sure that our artists’ work is being honored and seen and tended to and cared for and enjoyed. Because we feel that deeply about the value of what they’re doing.”

Last year, Aguilar and Fischbach moved Patron from its original home in River North to a bigger space in the old Alvin Theatre building in West Town. When Aguilar showed the new space to his family, his father recalled going there to see movies when he first arrived in the U.S. from Mexico in the mid-1970s. “He worked at a gas station a couple of blocks away,” says Aguilar. “He didn’t know English yet. They played Spanish-language movies, and so he would come watch movies there because he couldn’t find anywhere else to go…. Talk about the American Dream.” Chicago is that kind of town.

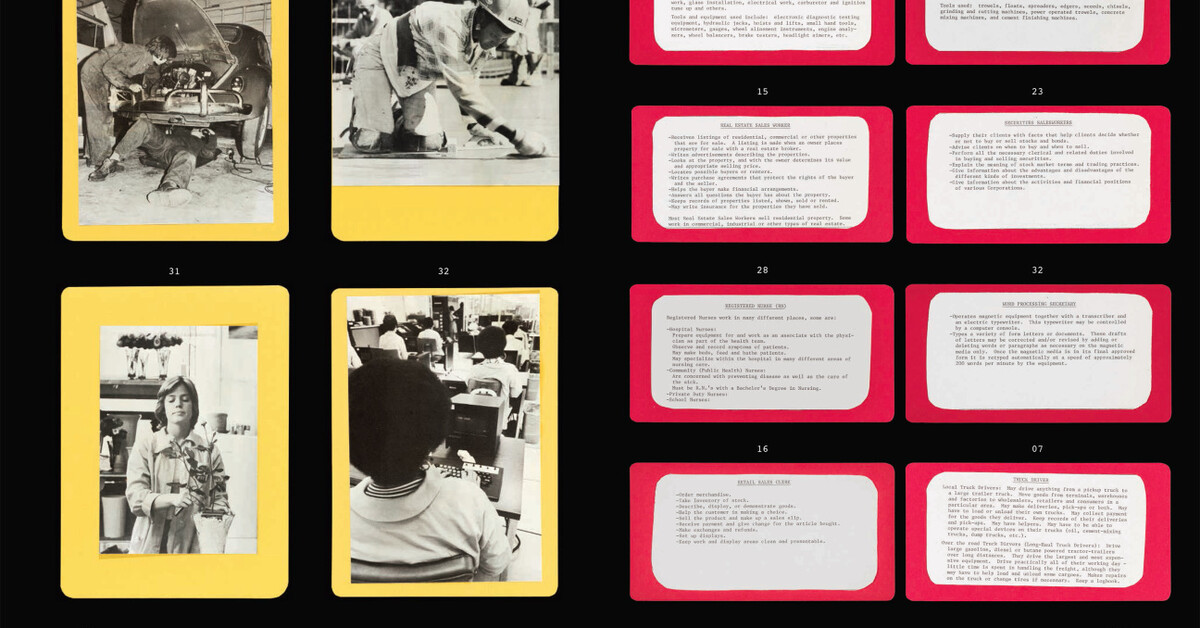

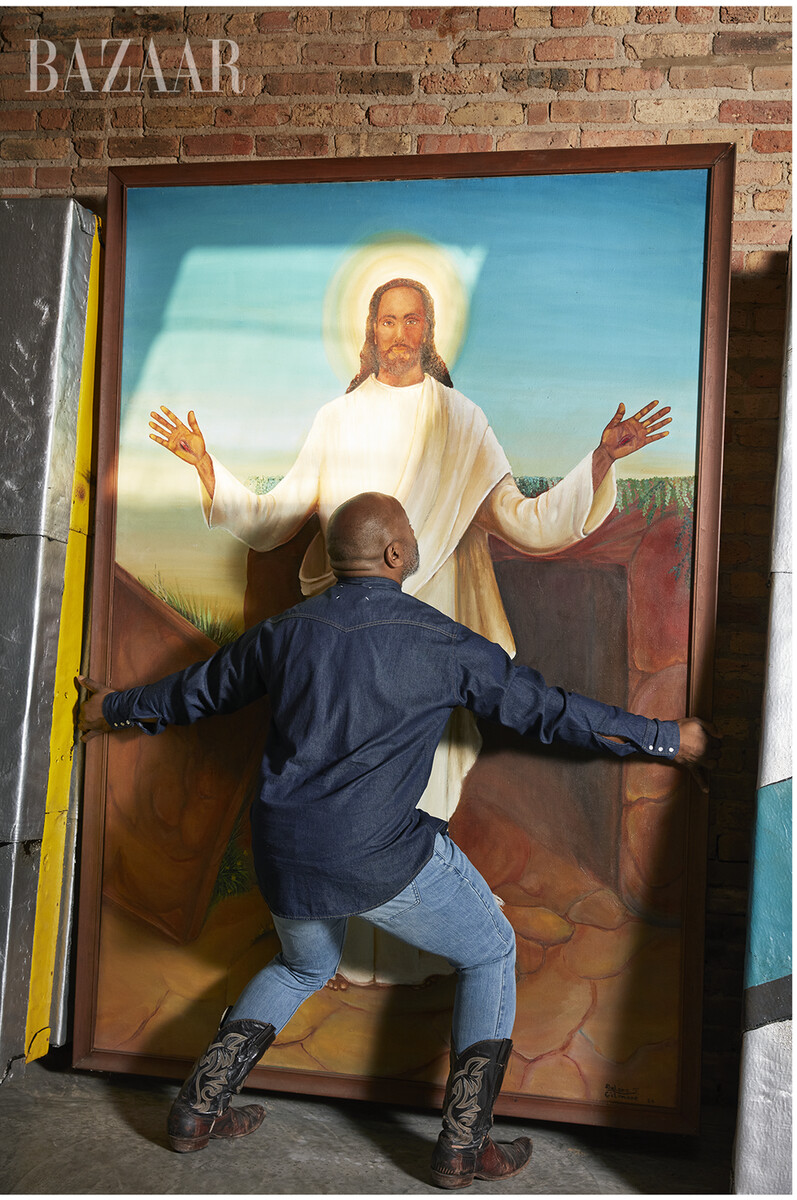

THEASTER GATES

Artist

Gates with a painting of a Black Jesus. Shirt, Maison Margiela. Jeans, Prada. Boots, his own.; JOHN EDMONDS

Over the past 16 years, Theaster Gates has helped transform the South Side through his work with his nonprofit Rebuild Foundation. In addition to the Stony Island Arts Bank, his portfolio of spaces and projects in Grand Crossing has grown to include his studio, which occupies an old Anheiser-Busch distribution center, a movie theater that shows films by Black directors, an art-centered 32-unit affordable housing complex, and a recently announced creative incubator that is being developed in a long-dormant elementary school building.

“People were leaving because there was no way to see that the future could look different.”

Gates’s work hasn’t completely remade the community. Its residents still struggled throughout the pandemic, the way so many others have in neighborhoods across the country where economics and opportunity never quite seem to align. But it has reignited something that may have been lost. “When I moved here in 2006, it was a place that had been desacralized,” Gates says. “People were leaving, not just because of the violence but in a way because there was no way to see that the future could look different.”

Gates, though, didn’t need to look far for examples of how artists—and art—could help cultivate that new vision. “The contributions of Gwendolyn Brooks, Margaret Taylor Burroughs, and Lorraine Hansberry can’t be overstated,” he says. “They understood, with the political fervor of their time, the importance of both being excellent in their craft and representing the people. Margaret Taylor Burroughs had a keen sense of how her influence could create opportunity for other Black and Brown artists. The same is true of Gwendolyn Brooks, who had the institution of teaching where she could train generations of writers and thinkers. They all invested deeply in the communities that they were a part of.”

LOUISE BERNARD

Director, the Museum at the Obama Presidential Center

Louise Bernard at Virtue, a soul-food restaurant on the South Side, with Dawoud Bey’s A Couple in Prospect Park (1990). Knit, turtleneck, and skirt, Prada. Earrings, Cartier.; JOHN EDMONDS

For former president Barack Obama and first lady Michelle Obama, Chicago is an essential character in one of the transformative stories in American history, which also just happens to be the story of their lives. “It’s where they found their footing,” says Louise Bernard, the director of the Museum at the forthcoming Obama Presidential Center. “It’s where they came together as a couple. It’s where they built their family. So this is a homecoming and an idea: this sense of giving back to the community and to the city that really made them.”

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

“[W]e’re thinking about a sense of the commons, a civic commons—of openness and access.”

Barack and Michelle Obama made all kinds of history during their time in the White House, not least with their selections of Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald respectively to paint their official portraits. So it should come as no surprise that art will play a crucial role in the Tod Williams– and Billie Tsien–designed Obama Presidential Center in Jackson Park, which will attempt, for the first time, to contextualize the achievements of the nation’s first Black president at scale—and like everything with the Obamas, the expectation is that the center will do that in ways that are like nothing we’ve ever seen before.

In mapping out the vision for the center, a governing concept has been to capture and chronicle not just what Barack Obama has accomplished in his life but the wider circle of people who helped make it all possible, which Bernard says is important to the former president. “President Obama is being really mindful in building a presidential center,” Bernard explains. “But his mindfulness is around the idea of those upon whose shoulders we stand…. We’re not thinking about a space that is dedicated only to a particular story. Rather, we’re thinking about a sense of the commons, a civic commons—of openness and access,” she continues. “We often think about presidential history and presidential narratives as being tied very much to the concept of policy, but for the president and for Mrs. Obama, it is about how that policy literally meets the people and vice versa.”

The center has already collaborated with Theaster Gates’s nearby Rebuild Foundation and deepening its engagement with and involved in the communities that surround it is an important part of that project. “There is simply something, I think, deeply meaningful about the South Side,” Bernard says. “Its connection to the long history of the Great Migration, but also to issues of post industrialization, and the lack of investment in this particular part of the city,” she offers. “It’s about thinking of the center as a hub and about the synergies that radiate out, the potential for partnership and collaboration that can lift up the South Side…. We often talk about the idea of bringing the world to the South Side and the South Side to the world. The [former president’s] story is deeply rooted in Chicago and deeply rooted specifically in the South Side, but we also have a national platform. It’s the story of the 44th president of the United States, but we also have a global reach.”

In addition to the Richard Hunt piece, a second commission has been announced by the artists and architect Maya Lin. The museum has also consulted with Chicago-based artists Andres L. Hernandez, Norman Teague, and Amanda Williams on the design of the exhibition spaces; both Hernandez and Williams are trained in architecture as well. “Many of the artists we work with naturally have a connection to built space and the idea of imagining more utopian understandings of built space,” says Bernard. “[We want to create] a civic commons, placing at the heart of it the idea of civil discourse, of dialogue across difference, and an understanding of how the arts can uplift people and inspire them to imagine the change they can create in their own communities.”

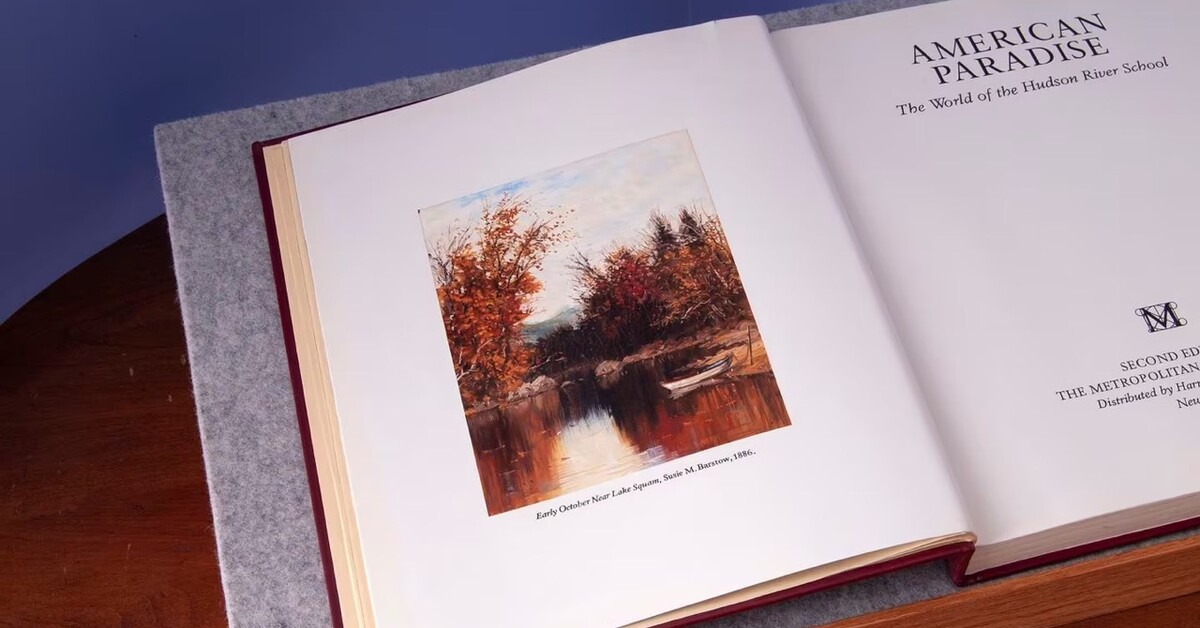

NICK CAVE

Artist

Nick Cave in his studio at Facility. Clothing and boots, his own.; JOHN EDMONDS

“To think that for four decades, I’ve been trying to bring light to the subjects of racism, injustice, inequality, police brutality—yes, I know that has been the impetus for the work, but to see it together, all of a sudden, the purpose became clear, the reason why,” says Nick Cave. We’re discussing “Forothermore,” the career-spanning survey of Cave’s work that opened earlier this year at MCA Chicago and moved to the Guggenheim in New York in November. Cave’s practice encompasses aspects of sculpture, installation, and performance, frequently incorporating found objects he has unearthed at flea markets and thrift stores. But it is the way that he has combined those elements in his deeply personal Soundsuits—perhaps best described as exuberant, wearable mixed-media art pieces that move with the body, which he began creating in 1992 as a response to the police beating of Rodney King—that has remained a consistent focus, part of an ongoing reckoning with the social, political, psychological, and physical dimensions of race and violence.

“Art has been my savior.”

It’s one that began shortly after he moved to Chicago in 1989 for a teaching job at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, having grown up in Missouri and then spending time in New York, where he trained for a period with the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. “When I arrived here, Rodney King happened,” Cave says. “I was feeling lost and disconcerted about my identity and place in the world. I knew no one here, but it gave me this space of reflection. It was the beginning of the Soundsuits. The work I was doing prior were these constructivist paintings, and all of a sudden it shifted and I was working from this place of consciousness. It just literally turned everything upside down.”

Cave has referred to Chicago as his “chosen hometown.” But if his own connections to the city run deep, then the feeling is mutual. The MCA Chicago survey was accompanied by another exhibition at the DuSable Museum called “The Color Is Fashion,” for which Cave and his brother Jack Cave, a fashion designer, crafted more than 40 couture pieces with a range of collaborators. This past spring, Cave also created a public video installation for the Art on theMART Foundation. “To be able to bring this work here and to share it and for us to have conversations, have a way in to collectively reflect on moments and how we move collectively forward—it was really what it was all about,” Cave says. “For me to think that this is how I have been dealing with the ongoing trauma, the ongoing Black trauma, and to know that I have been using this way of managing and working through those concerns, and healing in that process—it has been my savior. Art has been my savior.”

Cave has also continued to undertake projects through Facility, the live/work studio, performance, and exhibition space he developed in 2018 with his partner, Bob Faust, in an industrial building in Irving Park. During the pandemic, Cave’s graduating students in the Fashion, Body and Garment program he helped establish at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago did not have their thesis shows because of Covid-19 restrictions, so Cave gave them each solo shows at Facility. “I was like, ‘We have to turn the storefront galleries over to the graduate students,’” Cave says. “We’re extraordinarily grateful to be able to have this space to invite, to call and respond, and to expose the community, the world, to a different way of experiencing and engaging in art practice.”

MARIANE IBRAHIM

Gallerist

Mariane Ibrahim in her office at her gallery with Clotilde Jiménez’s Baptism at Night (2021). Jacket, blouse, and pants, Dior. Ring, Cartier.; JOHN EDMONDS

Since founding her namesake gallery in Seattle in 2012, Mariane Ibrahim has earned a global reputation for showing a diverse group of international artists of the African diaspora, such as Amoako Boafo, M. Florine Démosthène, and Chicago-based Carmen Neely. But the Somali-French gallerist, who closed her Seattle space in 2019 to set up shop in Chicago, made the move in large part because the kinds of narratives and ideas around race, movement, identity, and creative expression that she sought to highlight in her shows were intimately intertwined with the history and cultural life of the city itself. “There was something about the emergence of Black artists on the global art market that Chicago was already ahead of,” Ibrahim says. “Presenting a program focused on social change and bringing attention to artists of African descent—it’s not something trendy in Chicago. It has existed here for a long time.”

“Presenting a program focused on social change—it’s not something trendy in Chicago.”

Housed in an airy space in West Town next door to Monique Meloche and not far from Gray and Rhona Hoffman, Ibrahim’s gallery has quickly become an integral part of what she describes as an amalgamation of art spaces and organizations in Chicago that is more collegial than competitive. “The first thing that made the experience feel like ‘I’m going to be fine here’ is how welcoming my gallery peers were,” Ibrahim says. “When you have your contemporaries at other galleries sending you private messages, welcoming you and wishing you success, and then get to meet them one by one—not by my initiative, but by their initiatives—that is something that you may not find in other cities.” It’s a sense of community that extends to collectors. “You will go to every collector’s home in Chicago and 100 percent you will see local artists on the walls,” says Ibrahim, who also opened a Paris outpost of the gallery in 2021. “There is active participation from the collectors and patrons toward the arts.”

AMANDA WILLIAMS

Artist

Amanda Williams in her studio with early studies from the “CandyLadyBlack” painting series. Dress, Proenza Schouler. Ear climbers, medallion, cuffs, and ring, Almasika.; JOHN EDMONDS

Amanda Williams has warm memories of her childhood on the South Side. “I grew up on a great block,” she tells me. “We had a tight-knit community of neighbors who helped create fun memories of playing games as well as gatherings with families on weekends and holidays. Both my parents are from large families, so we loved getting together.” But Williams was also aware as a kid that their neighborhood was distinct in other ways. “I just knew from a young age that all parts of the city didn’t seem to get the same love. Why did buildings get torn down and nothing came back? Why weren’t potholes fixed or snow not plowed for days in winter? Why did we have to travel out of our neighborhood for grocery stores, certain restaurants, amenities?” she recalls. She didn’t know what to call it, but she could feel it. “I didn’t have language for systemic racism and inequity.”

“I didn’t have language for systemic racism and inequity.”

In 2017, Williams—now an artist with a degree in architecture from Cornell University—embarked on a project on the South Side, where she still lives and works. She and a group of friends and recruits went around the area painting condemned houses in vivid colors with strong cultural associations, like red, yellow, and blue. The series of works, titled “Color(ed) Theory,” was an extension of Williams’s ongoing interest in the ability of color to simultaneously describe race and chroma. “I’m trained as an architect, so problems are always taught to be seen as opportunities,” she says. “However, that single action of shrouding those structures also unlocked a larger recognition about the racist conditions that would create these dilapidated ‘canvases’ in the first place.”

In October, Williams was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship, joining the ranks of past Chicago-based MacArthur “geniuses” like Dawoud Bey and Kerry James Marshall. It’s a lineage that Williams is proud to be a part of. “Chicago’s creative community has always been robust,” she says. “Margaret Taylor Burroughs was pivotal for me and so many others. She was an artist, activist, institution builder, civic leader. She told me and every other child who would listen that they were an artist,” Williams offers. “I believed her.”

DAWOUD BEY

Artist

Dawoud Bey in a park near the Museum of Contemporary Photography at Columbia College Chicago. Jacket, shirt, and pants, Polo Ralph Lauren. Accessories, his own.; JOHN EDMONDS

“I think someone conspired to get us here. It was too good a coincidence,” says Dawoud Bey, who arrived in Chicago from his native New York in 1998. At that point, Bey’s art-making career was in full flight on the strength of groundbreaking photographic projects like “Harlem, U.S.A.” (1975–1979), which captured the lives and landscapes of an oft-underrepresented side of American life. Five years earlier, Bey had done a residency at the Museum of Contemporary Photography at Columbia College Chicago and the then director had reached out to see if he’d be interested in teaching there. Simultaneously, his then wife, the artist Candida Alvarez, was offered a teaching job at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. With a young son, they were looking for a modicum of stability, so they weighed the offers carefully. “I already knew a number of people in Chicago from that eight-week residency, and my friends and neighbors from Brooklyn, Kerry James Marshall and his wife, Cheryl Lynn Bruce, had moved here,” Bey says. “My only brother and his family lived here too, so that was a big plus for me and my family.”

“Chicago has never waited for New York’s approval. Chicago supports its own.”

A quarter century later, Bey has become a fixture in the city, where he continues to teach at Columbia College Chicago and generate potent and powerful work, like “Night Coming Tenderly, Black” (2017), a collection of images taken at locations thought to have once been a final stretch of the Underground Railroad, which was exhibited at the Art Institute of Chicago in 2019. “People in the art and culture community here seem to understand that we are all part of one ecosystem and that we all thrive when we encourage and support each other,” Bey says. “I think of Chicago as having the sensibility of a small town within a big city—‘small town’ because everyone knows each other and ‘big city’ because things happen here at a very high level of execution,” he offers. “Chicago has never waited for New York’s approval. Chicago supports its own.”

DENISE GARDNER

Board Chair, the Art Institute of Chicago

Denise Gardner at the Art Institute of Chicago with Kerry James Marshall’s Africa Restored (Cheryl as Cleopatra) (2003). Jacket, blouse, and trousers, Giorgio Armani. Earring, Repossi. Elsa Peretti ring, Tiffany & Co. Pumps, Manolo Blahnik.; JOHN EDMONDS

A longtime collector, Denise Gardner was named chair of the Art Institute of Chicago’s board of trustees in 2021. While Gardner is new to the role, she has been involved with the museum for nearly three decades, advocating for exhibitions of work by women, artists of color, and people from traditionally marginalized communities; funding acquisitions for the museum’s permanent collection; and helping to craft initiatives designed to foster greater equity, diversity, and accessibility. “Our first board president, Charles Hutchinson, stated that the Art Institute is ‘here for the public, not the few,’” says Gardner. “In an ideal world, the Art Institute of Chicago is a cultural gathering space where guests of all backgrounds and ages feel welcome and appreciate there is something here for them.

“In an ideal world, the Art Institute of Chicago is a cultural gathering space.”

Gardner has a background in marketing and advertising, having worked alongside her husband, Gary Gardner, in the health, beauty, and personal-care spaces. As collectors, they have focused primarily on artists of the African diaspora. They’ve also been known for their willingness to invest in young talent: Their collection includes early pieces by Sanford Biggers, Bethany Collins, Amy Sherald, and Amanda Williams.

For Gardner, there is a tradition of mentorship that is also an integral part of the art world in Chicago—something she has found important in her own life. “I owe deep gratitude first and foremost to Jetta Jones,” says Gardner. “She was the museum’s first Black female trustee. Twenty-eight years ago, she invited me to volunteer at the museum, which began my journey toward becoming board chair. I also enjoyed the mentorship of Joan Small. She was Chicago’s deputy commissioner of cultural affairs and a fellow museum leader. She spent a great deal of time helping me understand arts organizations, effective cultural programming, and stakeholder management. I miss them both dearly. I’m also grateful for fellow trustee and former gallery owner Isobel Neal. Isobel introduced me and my family to all the outstanding artists of our time: Charles Alston, Elizabeth Catlett, and others. I’m inspired by her accomplishments and by her willingness to share her knowledge.”

CANDIDA ALVAREZ

Artist

Candida Alvarez at Monique Meloche gallery with Are you listening to this? (2022). Dress, Simone Rocha. Earrings, Ten Thousand Things.; JOHN EDMONDS

A New York native, Candida Alvarez has served as a professor of painting and drawing at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago for the past 24 years. But it was only in 2020, just before the pandemic shut down the world, that Alvarez had her first proper gallery show in the city at Monique Meloche. “Estoy Bien” featured a group of what Alvarez refers to as “air paintings,” which are created on recycled PVC mesh from an outdoor installation and hung on freestanding aluminum frames.

“To have amazing creative people surrounding you and being in conversation with you is a gift.”

Alvarez’s vibrantly colorful paintings combine elements of abstraction and representation and frequently draw on history, memory, and her own Puerto Rican heritage. The “Estoy Bien” pieces, though, were especially personal, informed by the death of her father in 2017, just before Hurricane Maria descended upon Puerto Rico, where her sister had gone to stay with her mother. Her family made it through the storm safely and managed to travel to the continental U.S., but processing the events through her art also marked the beginning of a prolific creative period for Alvarez, who that same year enjoyed her most expansive survey to date at the Chicago Cultural Center and had her work incorporated by Rei Kawakubo into a pair of Comme des Garçons menswear collections. Her work is currently a part of two new exhibitions, “Forecast Form” at MCA Chicago and “no existe un mundo poshuracán: Puerto Rican Art in the Wake of Hurricane Maria” at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art. “Teaching gave me the opportunity to really observe my process, to give it a language,” says Alvarez. “To have these amazing creative people surrounding you and being in conversation with you is a gift.”

During the pandemic, Alvarez purchased a property in Western Michigan and relocated her studio there, making the 90-minute commute from her South Loop condo. For someone who has spent her life in urban environments, buying a house in the country was a bold step. But Alvarez says the greenery reminds her family’s home in Puerto Rico. “I think that there is something about that relationship to land that must be in my DNA because I didn’t even hesitate,” she offers. “But it was safe because I still have Chicago.”

BETHANY COLLINS

Artist

Bethany Collins in her studio with She Flung the Roses in the Air (2022) and Ah! May the Red Rose Live Alway (2022) from her “Rose Ballad” series. Jumpsuit, Brunello Cucinelli.; JOHN EDMONDS

Bethany Collins’s early career as an artist was an itinerant one. She grew up and went to college in Alabama before moving to Georgia for graduate school, doing a year as an artist in residence at New York’s Studio Museum in Harlem and spending time in Nebraska, California, and New Hampshire along the way. But it was while attending a Black Artists Retreat hosted by Theaster Gates on the South Side that Collins first thought that she might want to put down roots in Chicago, where she has now lived for the past seven years. “Chicago was one of the main tributaries out of the South during the Great Migration, so on the South Side, it still has these echoes of home for me,” Collins says. “Being from Alabama, I need elbow room. I need space. Chicago has enough of that,” she explains. “But Chicago is also a really big city that has all the infrastructure to support my career, so I could stay here and belong to a place again.”

“The livability of the city lets you have time and space to do more, to take more risks.”

The notion of place figures heavily in Collins’s work, which examines the interrelationships between race, identity, and language. Some of her most recent work revolves around contrafactum, a musical term that refers to songs where the lyrics have been changed to create different meanings without a substantial change to the music or melody. Collins has been mining the American songbook and poring over archival sheet music as a way of highlighting how familiar songs were rewritten to support different causes, ideologies, and agendas. “It was a more common early-American practice where you would keep a well-known melody consistent, but then you would rewrite the lyrics so that you could do a kind of call and response and rewrite it for different political or social causes,” Collins says. “The first hymnal I made bound together 100 versions of ‘America (My Country, ’Tis of Thee),’” she explains. “They’d rewrite the lyrics to the same tune, but in support of suffrage or temperance. The Confederacy had its versions. Abolitionists had their versions. So these different versions are in utter disagreement about what it means to be patriotic and to belong to this place…. All that’s left are these 100 dissenting versions of what it means to be American.”

For Collins, the Chicago years have been productive ones. “When I moved here, I was making maybe two bodies of work that I was becoming known for, but now I feel like I can make anything. Everything is open to me,” she says. “The livability of the city lets you have time and space to do more, to take more risks.”