Artist Carmen Winant on Building a New Visual Language Around Abortion

VanityFair / Aug 8, 2023 / by Laura Regensdorf / Go to Original

“The last safe abortion,” a new installation at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, brings together archival and new photographs of Midwest health clinics, centering imagery of workplace camaraderie and intergenerational care.

Who gets to decide what abortion looks like? In Carmen Winant’s latest exhibition, “The last safe abortion,” on view at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, a wall of tiled-together photographs offers a sprawling community portrait. A clinic employee cradles a corded phone beside a desktop copy of The New Our Bodies, Ourselves. Two hands press gently on a lower back; another massages a foot. There’s a pile of activist pins; a snowwoman with one fist in the air; a display board of services available at Iowa City’s Emma Goldman Clinic, under the tagline “Health Care for Women, by Women.” The 1,600 or so vintage photos—drawn from clinics, university archives, and historical societies across the Midwest—show the routine day-to-day of meetings and waiting-room decor. In one of these “drugstore prints” (as Winant, an ’80s baby, calls them), a pinned-up quilt with green and red squares bears a four-word benediction: “You are safe here.”

More than a year after the Supreme Court ruled to overturn the constitutional right to abortion, the comfort of that phrase now begs a somber rejoinder: Safe till when? “I’ve been experiencing this whiplash myself for some time now,” says Winant, describing the swing from despair to action-minded resolve she has felt in the years developing the exhibition. The artist is speaking on a recent afternoon from Ohio—a state she has called home for nearly a decade, and one whose draconian abortion restrictions led a 10-year-old rape victim to flee to Indiana last year for medical care. The subject of abortion mirrors another of Winant’s quietly radical projects: My Birth, a monumental collection of birth-related images installed as part of MoMA’s “Being: New Photography 2018.” In some ways, both bodies of work set out to recontextualize a familiar topic by drawing on a haul of existing imagery. But this time around, as the post-Roe ground shifted in real time, she couldn’t let the visual record of abortion care exist solely in the past.

“I’m trained in photography, but I had to reteach myself how to use the camera to make those pictures,” says Winant, referring to a series that fills one oversized bulletin board, taken while visiting a handful of providers in the Midwest. (One has since shuttered.) “I felt like it was really important to demonstrate that, while the archive did cross decades, this is not ossified. This is happening in the present moment, in the present hour.” Another discrete group of images in the show comes from the Friendship Medical Center, a Black-run clinic in Chicago that operated for nearly two decades beginning in the early 1970s.

For Winant, who teaches at Ohio State University, with an endowed position as the Roy Lichtenstein Chair of Studio Art, the importance of community engagement looms large, as she discusses in the conversation below. “I’m not someone who believes that artwork does all the work,” she says, stressing how meaningful it has been to connect with older abortion providers. “I hope I’m not romanticizing it, but I’m looking to find strategies. Emotional strategies for resilience, but also practical, on-the-ground strategies.” The subject of this week’s special election in Ohio comes up: Republican legislators seek to move the goalpost for passing amendments to the State Constitution—from a simple majority to 60 percent—with the underlying intent to thwart a referendum on abortion protections. She points to the sticker on her shirt. “I voted early today,” says Winant, who will spend the intervening days in Minneapolis, hand-taping hundreds of photos to the gallery wall. Given Minnesota’s status as a safe haven for abortion care, it’s a fitting place for the show.

Vanity Fair: In past work, you’ve touched on themes of childbirth, violence against women, and lesbian separatist communities. Is this the first time you’ve directly addressed abortion?

Carmen Winant: I had to ask myself that question too because it’s such a core tenet of my life and of my value structure. So much of my feminism is oriented around reproductive justice and rights. That’s why I trip up at this question because I think to myself, “Yes, of course I have,” but then I’m like, “No, actually—you’ve done this sort of activism, or you’ve donated these works to raise money.” Why has it taken so long for me to figure out how to put it into my artwork or have the bravery required to do that? I’m not really sure I can answer that question, except that it feels really vulnerable. And because it’s so politicized, there’s always the worry of the pushback, or that on my end it’ll feel really heavy-handed.

It’s interesting: Judy Chicago is having this retrospective at the New Museum later this year, and they asked me to write an essay on her Birth Project, and it was really clarifying for me because it became so much about abortion. I was writing the essay as the Dobbs decision was coming down, and was thinking, “How can we think about the Birth Project 50 years out?” And the answer to me was: What is the visuality that attends abortion? Because, of course, the right to be pregnant has everything to do with the right to be unpregnant. This is the first time, directly, that I’ve centered [abortion] as work, but in other ways it feels so entangled for me with everything that you brought up, in and around bodily choice and autonomy but also liberation. It’s easy to do this when you look back retrospectively, and you can line everything up.

It almost makes you wonder, of the 2,000 or so images in My Birth, if there might have been a photo of some circumstance involving abortion. In a framework about birth, invariably abortion exists alongside it. It’s why so many mothers are so devotedly in support of abortion rights.

I can’t remember what the statistic is, but I think that most people who have abortions over the age of 35 or something in this country are mothers. I’ve had one abortion, and it was after I already had one child. It’s really entangled in not just the politics of mothering at the 30,000-foot level, but on the ground—what it takes and feels like. You’re reminding me of this visual essay that came out in the New York Times some months ago, showing photographs of fetal tissue at just a few weeks. It was so profound for me to see, and I think for others to see, just what it is that we’re talking about.

Where I teach at OSU, the art building is right on the quad, and directly outside the exit is where the anti-abortion activists set up with their huge banners of so-called aborted fetuses. I started thinking—when I saw that photo series in the New York Times, and I was confronted by these people, day in and day out—just about how much the anti-abortion people have weaponized photography, specifically, in their effective war against abortion rights. I was thinking, how could I orient a project around not just, “Oh, this is what it looks like,” but actually a vocabulary around abortion work. Maybe not to weaponize it, but to countermand and think photographically in that project.

What visual vocabulary did emerge? Women on the phone is one thing that comes to mind.

There are so many women on the phone! It’s incredible. That’s a good entry point to talking about what the visuality is. The pictures are so regular and so unsensational. Even where there were photographs in the archives of protestors or the cops or confrontations—and there weren’t that many, but there were some—I found myself steering around them because it felt really important to center the pictures of women: on the phone, in meetings, sanitizing medical supplies, their staff birthday parties. That is what they describe as “the work of the work.” Even when I went to the clinics to photograph, the phone is fucking ringing off the hook. They’re rotating, taking turns answering the phone, sometimes two and three at a time.

It’s interesting that we’re talking about the visual plane of the work, but the accompanying sound is so insistent and jarring—the auditory equivalent of a flashing warning light. How did you come upon the title of the exhibition?

I’m glad it is evocative of that. This was an almost four-year project, and in that time, I met a lot of different abortion care workers—and I use that word because some of them are staffers, some of them are physicians. I ended up working with a half-dozen clinics in and around the Midwest. That was such a meaningful part of the project, invisible in certain ways, but I hope it’s visible because how else is this kind of access garnered? I almost think, if this doesn’t sound too corny, the artwork is the thing that helps me arrive at the relationships and the consciousness. Not the other way around.

Almost all of them said the exact same sentence to me, verbatim, at some point in conversation, if not across multiple points in conversation, which was: “We will offer the last safe abortion in blank”—Ohio, North Dakota, Indiana. I was struck by how they mirrored each other in saying that, and also by the phrase itself. They are so resilient. They’re not going away. They’ll do their work. And on the other hand, it’s elegiac. It’s not a matter of if, but when, and that was so hard to hear because I look to them. There’s some young folks but also people who have been in the game for decades, and I would be like, “Tell me how to become unstuck in my paralysis, how to be as resilient as you are.” And they would just turn around and say, “I feel despair.” Some days, the project was hopeful, but on most days, I would be lying if I said it didn’t have a lot of agony that attended it.

These days, when I hear mention of Ohio, I think about a 10-year-old girl who needs an abortion. How did the evolving headlines and changes in legislation shape the work, given your proximity?

On some days, I felt like, “Why am I making fucking art that’s going to go in a museum? Why am I not answering the phone?” I was collecting signatures for the referendum and doing my little part where I could, but I want to be honest about that negotiation with myself. Paula Rego’s abortion drawings are so famous because they influenced actual policy in Portugal, but, of course, that kind of story is rare. It was totally surreal because when I started this project, I was one of many people who was in denial, despite all the alarm bells that were going off, about the forthcoming end of Roe. Mostly I felt more and more determined to make the work. I wavered about the best place to put my energies, and ultimately I felt the thing that I could do was not just to make the work and put it in a museum, but to build these relationships with these abortion care providers.

With Minnesota’s protections for abortion access, the Minneapolis Institute of Art seems like an opportune place for the show.

Totally. The museum has been pretty incredible. I’ve been charging forward, just waiting for them to flinch, and they haven’t been flinching. Recently, in the past week, we have had conversations about what happens if there are protests, and the National Right to Life organization is in St. Paul, just next door. I’ve been working with this very smart feminist curator, Casey Riley, and the staff has been supportive. It was really important for me to put “abortion” in the title of the show. I believe in “reproductive health care” and “justice” and so forth, but I feel like sometimes you have to name it.

If the exhibition is your output from processing the Dobbs decision, what was your input, in terms of books or podcasts or such?

I’m sorry to say that I am obsessive about it. Sometimes my partner will be like, “You need to take a step back.” I read this incredible book on the Jane Collective in Chicago. I learned about this council of clergy—they were largely in and around New York, pre-Roe—from a podcast, which led me to all this reading material around the clergy men and women who provided safe passage. Meanwhile, I’m talking to all these old-school midwives and abortion care providers about how they basically set up free abortion funds and shuttled people to New York from Ohio, which is going to start happening again, as wild and fucked up as that is. It’s easy to look back to the ’70s. I do this all the time and feel sentimental towards an era that I didn’t experience—which is much more nuanced, I’m sure, than I’m understanding. It’s important for me too to think about the contemporary struggles in Ireland, Argentina, Mexico. Looking to Central and South America, and the feminists down there, is really mind-blowing and profound.

When My Birth debuted, you talked about how hard it was to find people of color represented in early birthing manuals and other photographic records—and how an artwork composed of vintage images inherently reflected that lack of diversity. What was the research process like this time?

I learned so much from that MoMA piece, from that process, and one of the things that I learned, no surprise, is that one can—I can—do more harm by reinscribing these omissions. I put it in the [My Birth] wall text and I put it in my one-minute audio tour, and I never talked about the work without talking about those omissions in the archive and working to center them as the subject as much as anything else. But I learned that wasn’t enough. The criticism that I received over it was really valid, and I had to sit with and evolve. No way of working is going to be totally pure. Ethical imperfections abound.

After that, I wanted to do a couple things. First of all, I wanted to work directly with people, as opposed to—and this is no value judgment on any way of working—but I was pretty alienated in the studio, culling all this material and making these arrangements, and the work was about solidarity. It was about building relationships and making these social alliance networks, and I eventually just felt like that has to be how I make the work and not just what the work is about. And the other thing was: Where do these archives exist—again, nothing is perfect—where there is already multiracial coalition, where there is already intergenerational exchange?

One part of the exhibition is these five oversized enclosed display cases, like what you see outside of a doctor’s office or library. That work will hold one archive: the archive from the Friendship abortion clinic, which was a Black-run and -operated clinic in Chicago for just shy of two decades. It was shuttered about 12 years ago. [This interest in representation], I’m not doing it to check a box. It really feels like a way to deepen my consciousness as a feminist, to think about how important it is to have disabled people in the archive, to have queer people and trans people in an abortion archive. So doing those two things together—working directly with people, and going to archives where that kind of coalition and solidarity already exists—has been really meaningful.

That sense of community really comes through in the grid of prints. One photo shows a Take Your Child to Work Day sign; others show hands gently on a patient’s body.

There’s this incredible series of photographs from the Iowa Women’s Archive, which is at the University of Iowa, and it’s from a clinic in Iowa City that donated all their material. There are tens and tens of pictures that almost appear to be massage. They’re so tender and extraordinary, and I’m so happy to have pictures of deep friendship and connection and support next to the pictures of answering the phone, next to the picture of Take Your Daughter to Work Day. It all feels like it’s of a piece.

The waiting rooms, too, caught my eye. Now, when we think about the word waiting in the context of abortion, it’s related to the ill-intentioned wait times that make procedures inconvenient or impossible. Here, waiting comes back to a more neutral space.

I’m thinking of one suite of pictures from Preterm, in Cleveland, which is the oldest abortion provider in Ohio and sort of where this project began. There are maybe 60 pictures that I’m assuming were made for educational purposes, and they show a woman who is [hypothetically] going through the process of getting a surgical abortion. It starts with her dialing the phone. Someone’s on the other end. She checks in. She waits in the waiting room. She looks through a magazine. She gets her blood taken. She gets fitted for a diaphragm. She waits in the waiting room after, and then she walks out. I just thought it was so poignant. I love what could be demonstrated and taught holistically through photographs.

It reminds me of how nurses prepare you for what’s ahead by saying, “This is going to be a little cold,” or “There’s going to be a little bit of pressure here.” Photography can do that too.

Almost better than reading or a written description. That’s the most head-on example because you see somebody walking through the steps. I’ve had an abortion—I’ve never seen that. You know what I mean? I came into that series early, and it was one of the things that made me feel like there’s a project here.

On the flip side, were there holes in the image archive that spurred you to make your own pictures?

The curator, Casey, was really the one who pushed me because I was visiting the clinics. I think I felt really nervous to insert myself or make myself a protagonist here, and one thing that Casey was continually reminding me was, “You’re in this, whether you like it or not. You’re collecting. You’re editorializing in some sense. And not only that, but your presence is important. You are talking about intergenerational exchange and inheritance. How does that become visible?” I feel so jazzed to be able to put those pictures of those women in a museum.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Who gets to decide what abortion looks like? In Carmen Winant’s latest exhibition, “The last safe abortion,” on view at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, a wall of tiled-together photographs offers a sprawling community portrait. A clinic employee cradles a corded phone beside a desktop copy of The New Our Bodies, Ourselves. Two hands press gently on a lower back; another massages a foot. There’s a pile of activist pins; a snowwoman with one fist in the air; a display board of services available at Iowa City’s Emma Goldman Clinic, under the tagline “Health Care for Women, by Women.” The 1,600 or so vintage photos—drawn from clinics, university archives, and historical societies across the Midwest—show the routine day-to-day of meetings and waiting-room decor. In one of these “drugstore prints” (as Winant, an ’80s baby, calls them), a pinned-up quilt with green and red squares bears a four-word benediction: “You are safe here.”

More than a year after the Supreme Court ruled to overturn the constitutional right to abortion, the comfort of that phrase now begs a somber rejoinder: Safe till when? “I’ve been experiencing this whiplash myself for some time now,” says Winant, describing the swing from despair to action-minded resolve she has felt in the years developing the exhibition. The artist is speaking on a recent afternoon from Ohio—a state she has called home for nearly a decade, and one whose draconian abortion restrictions led a 10-year-old rape victim to flee to Indiana last year for medical care. The subject of abortion mirrors another of Winant’s quietly radical projects: My Birth, a monumental collection of birth-related images installed as part of MoMA’s “Being: New Photography 2018.” In some ways, both bodies of work set out to recontextualize a familiar topic by drawing on a haul of existing imagery. But this time around, as the post-Roe ground shifted in real time, she couldn’t let the visual record of abortion care exist solely in the past.

“I’m trained in photography, but I had to reteach myself how to use the camera to make those pictures,” says Winant, referring to a series that fills one oversized bulletin board, taken while visiting a handful of providers in the Midwest. (One has since shuttered.) “I felt like it was really important to demonstrate that, while the archive did cross decades, this is not ossified. This is happening in the present moment, in the present hour.” Another discrete group of images in the show comes from the Friendship Medical Center, a Black-run clinic in Chicago that operated for nearly two decades beginning in the early 1970s.

For Winant, who teaches at Ohio State University, with an endowed position as the Roy Lichtenstein Chair of Studio Art, the importance of community engagement looms large, as she discusses in the conversation below. “I’m not someone who believes that artwork does all the work,” she says, stressing how meaningful it has been to connect with older abortion providers. “I hope I’m not romanticizing it, but I’m looking to find strategies. Emotional strategies for resilience, but also practical, on-the-ground strategies.” The subject of this week’s special election in Ohio comes up: Republican legislators seek to move the goalpost for passing amendments to the State Constitution—from a simple majority to 60 percent—with the underlying intent to thwart a referendum on abortion protections. She points to the sticker on her shirt. “I voted early today,” says Winant, who will spend the intervening days in Minneapolis, hand-taping hundreds of photos to the gallery wall. Given Minnesota’s status as a safe haven for abortion care, it’s a fitting place for the show.

Winant installs the central grid of photographs in “The last safe abortion,” at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. COURTESY OF MINNEAPOLIS INSTITUTE OF ART.

Vanity Fair: In past work, you’ve touched on themes of childbirth, violence against women, and lesbian separatist communities. Is this the first time you’ve directly addressed abortion?

Carmen Winant: I had to ask myself that question too because it’s such a core tenet of my life and of my value structure. So much of my feminism is oriented around reproductive justice and rights. That’s why I trip up at this question because I think to myself, “Yes, of course I have,” but then I’m like, “No, actually—you’ve done this sort of activism, or you’ve donated these works to raise money.” Why has it taken so long for me to figure out how to put it into my artwork or have the bravery required to do that? I’m not really sure I can answer that question, except that it feels really vulnerable. And because it’s so politicized, there’s always the worry of the pushback, or that on my end it’ll feel really heavy-handed.

It’s interesting: Judy Chicago is having this retrospective at the New Museum later this year, and they asked me to write an essay on her Birth Project, and it was really clarifying for me because it became so much about abortion. I was writing the essay as the Dobbs decision was coming down, and was thinking, “How can we think about the Birth Project 50 years out?” And the answer to me was: What is the visuality that attends abortion? Because, of course, the right to be pregnant has everything to do with the right to be unpregnant. This is the first time, directly, that I’ve centered [abortion] as work, but in other ways it feels so entangled for me with everything that you brought up, in and around bodily choice and autonomy but also liberation. It’s easy to do this when you look back retrospectively, and you can line everything up.

It almost makes you wonder, of the 2,000 or so images in My Birth, if there might have been a photo of some circumstance involving abortion. In a framework about birth, invariably abortion exists alongside it. It’s why so many mothers are so devotedly in support of abortion rights.

I can’t remember what the statistic is, but I think that most people who have abortions over the age of 35 or something in this country are mothers. I’ve had one abortion, and it was after I already had one child. It’s really entangled in not just the politics of mothering at the 30,000-foot level, but on the ground—what it takes and feels like. You’re reminding me of this visual essay that came out in the New York Times some months ago, showing photographs of fetal tissue at just a few weeks. It was so profound for me to see, and I think for others to see, just what it is that we’re talking about.

Where I teach at OSU, the art building is right on the quad, and directly outside the exit is where the anti-abortion activists set up with their huge banners of so-called aborted fetuses. I started thinking—when I saw that photo series in the New York Times, and I was confronted by these people, day in and day out—just about how much the anti-abortion people have weaponized photography, specifically, in their effective war against abortion rights. I was thinking, how could I orient a project around not just, “Oh, this is what it looks like,” but actually a vocabulary around abortion work. Maybe not to weaponize it, but to countermand and think photographically in that project.

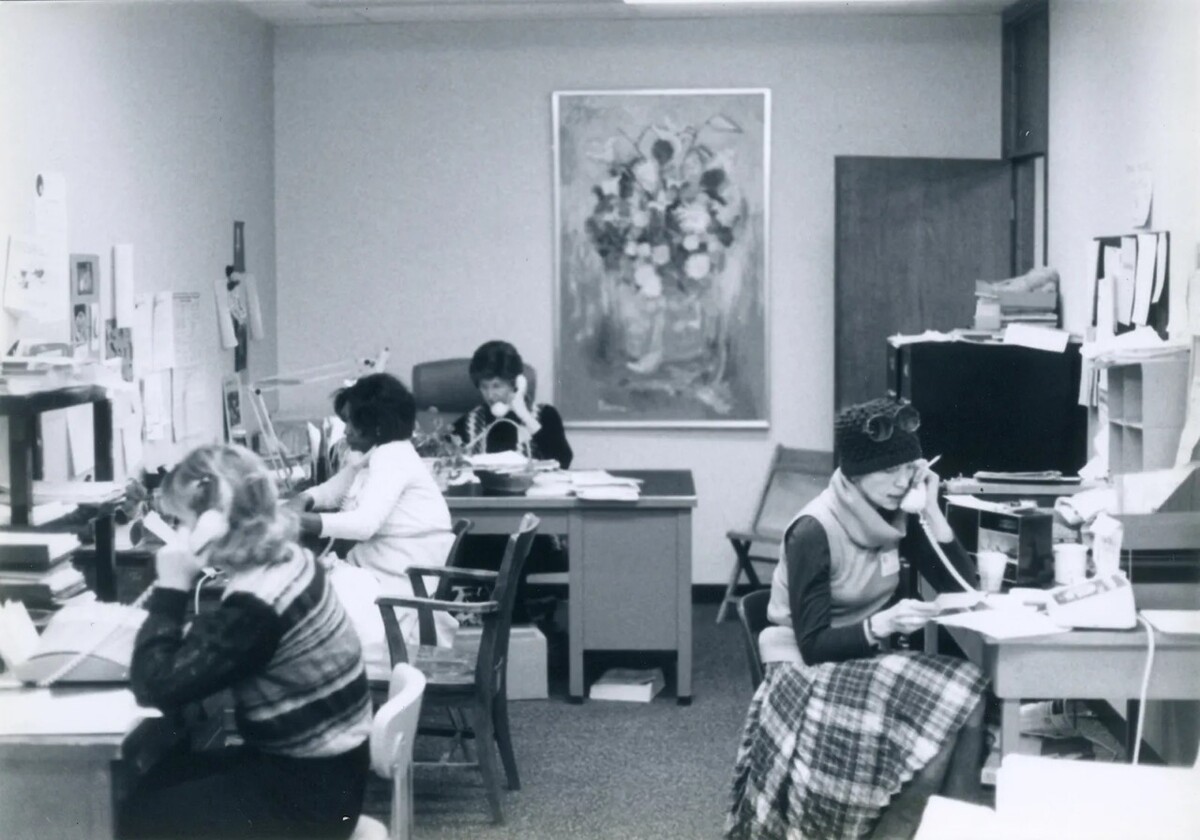

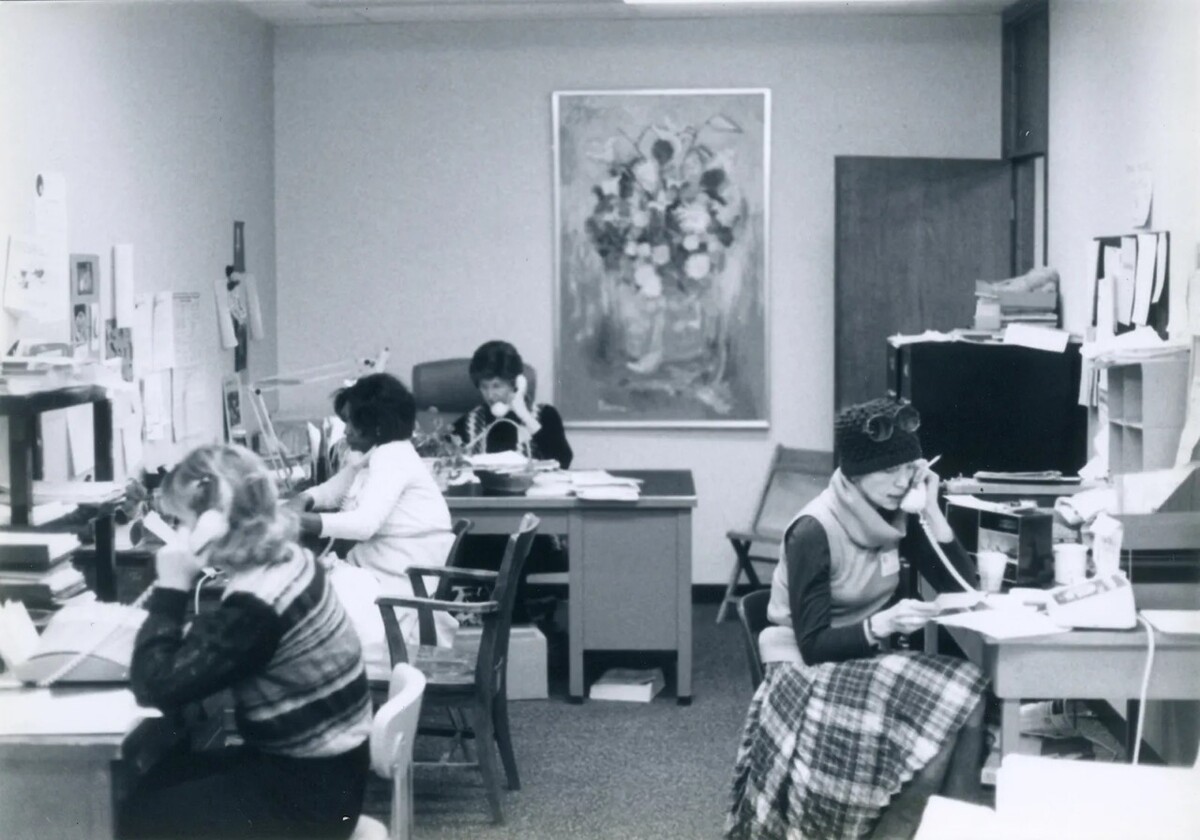

An image of clinic workers in the exhibition. COURTESY OF SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY.

What visual vocabulary did emerge? Women on the phone is one thing that comes to mind.

There are so many women on the phone! It’s incredible. That’s a good entry point to talking about what the visuality is. The pictures are so regular and so unsensational. Even where there were photographs in the archives of protestors or the cops or confrontations—and there weren’t that many, but there were some—I found myself steering around them because it felt really important to center the pictures of women: on the phone, in meetings, sanitizing medical supplies, their staff birthday parties. That is what they describe as “the work of the work.” Even when I went to the clinics to photograph, the phone is fucking ringing off the hook. They’re rotating, taking turns answering the phone, sometimes two and three at a time.

It’s interesting that we’re talking about the visual plane of the work, but the accompanying sound is so insistent and jarring—the auditory equivalent of a flashing warning light. How did you come upon the title of the exhibition?

I’m glad it is evocative of that. This was an almost four-year project, and in that time, I met a lot of different abortion care workers—and I use that word because some of them are staffers, some of them are physicians. I ended up working with a half-dozen clinics in and around the Midwest. That was such a meaningful part of the project, invisible in certain ways, but I hope it’s visible because how else is this kind of access garnered? I almost think, if this doesn’t sound too corny, the artwork is the thing that helps me arrive at the relationships and the consciousness. Not the other way around.

Almost all of them said the exact same sentence to me, verbatim, at some point in conversation, if not across multiple points in conversation, which was: “We will offer the last safe abortion in blank”—Ohio, North Dakota, Indiana. I was struck by how they mirrored each other in saying that, and also by the phrase itself. They are so resilient. They’re not going away. They’ll do their work. And on the other hand, it’s elegiac. It’s not a matter of if, but when, and that was so hard to hear because I look to them. There’s some young folks but also people who have been in the game for decades, and I would be like, “Tell me how to become unstuck in my paralysis, how to be as resilient as you are.” And they would just turn around and say, “I feel despair.” Some days, the project was hopeful, but on most days, I would be lying if I said it didn’t have a lot of agony that attended it.

These days, when I hear mention of Ohio, I think about a 10-year-old girl who needs an abortion. How did the evolving headlines and changes in legislation shape the work, given your proximity?

On some days, I felt like, “Why am I making fucking art that’s going to go in a museum? Why am I not answering the phone?” I was collecting signatures for the referendum and doing my little part where I could, but I want to be honest about that negotiation with myself. Paula Rego’s abortion drawings are so famous because they influenced actual policy in Portugal, but, of course, that kind of story is rare. It was totally surreal because when I started this project, I was one of many people who was in denial, despite all the alarm bells that were going off, about the forthcoming end of Roe. Mostly I felt more and more determined to make the work. I wavered about the best place to put my energies, and ultimately I felt the thing that I could do was not just to make the work and put it in a museum, but to build these relationships with these abortion care providers.

With Minnesota’s protections for abortion access, the Minneapolis Institute of Art seems like an opportune place for the show.

Totally. The museum has been pretty incredible. I’ve been charging forward, just waiting for them to flinch, and they haven’t been flinching. Recently, in the past week, we have had conversations about what happens if there are protests, and the National Right to Life organization is in St. Paul, just next door. I’ve been working with this very smart feminist curator, Casey Riley, and the staff has been supportive. It was really important for me to put “abortion” in the title of the show. I believe in “reproductive health care” and “justice” and so forth, but I feel like sometimes you have to name it.

If the exhibition is your output from processing the Dobbs decision, what was your input, in terms of books or podcasts or such?

I’m sorry to say that I am obsessive about it. Sometimes my partner will be like, “You need to take a step back.” I read this incredible book on the Jane Collective in Chicago. I learned about this council of clergy—they were largely in and around New York, pre-Roe—from a podcast, which led me to all this reading material around the clergy men and women who provided safe passage. Meanwhile, I’m talking to all these old-school midwives and abortion care providers about how they basically set up free abortion funds and shuttled people to New York from Ohio, which is going to start happening again, as wild and fucked up as that is. It’s easy to look back to the ’70s. I do this all the time and feel sentimental towards an era that I didn’t experience—which is much more nuanced, I’m sure, than I’m understanding. It’s important for me too to think about the contemporary struggles in Ireland, Argentina, Mexico. Looking to Central and South America, and the feminists down there, is really mind-blowing and profound.

The photographs in the show, including this blood-pressure check, are “so unsensational,” says Winant. COURTESY OF IOWA WOMEN’S ARCHIVE, UNIVERSITY OF IOWA.

When My Birth debuted, you talked about how hard it was to find people of color represented in early birthing manuals and other photographic records—and how an artwork composed of vintage images inherently reflected that lack of diversity. What was the research process like this time?

I learned so much from that MoMA piece, from that process, and one of the things that I learned, no surprise, is that one can—I can—do more harm by reinscribing these omissions. I put it in the [My Birth] wall text and I put it in my one-minute audio tour, and I never talked about the work without talking about those omissions in the archive and working to center them as the subject as much as anything else. But I learned that wasn’t enough. The criticism that I received over it was really valid, and I had to sit with and evolve. No way of working is going to be totally pure. Ethical imperfections abound.

After that, I wanted to do a couple things. First of all, I wanted to work directly with people, as opposed to—and this is no value judgment on any way of working—but I was pretty alienated in the studio, culling all this material and making these arrangements, and the work was about solidarity. It was about building relationships and making these social alliance networks, and I eventually just felt like that has to be how I make the work and not just what the work is about. And the other thing was: Where do these archives exist—again, nothing is perfect—where there is already multiracial coalition, where there is already intergenerational exchange?

One part of the exhibition is these five oversized enclosed display cases, like what you see outside of a doctor’s office or library. That work will hold one archive: the archive from the Friendship abortion clinic, which was a Black-run and -operated clinic in Chicago for just shy of two decades. It was shuttered about 12 years ago. [This interest in representation], I’m not doing it to check a box. It really feels like a way to deepen my consciousness as a feminist, to think about how important it is to have disabled people in the archive, to have queer people and trans people in an abortion archive. So doing those two things together—working directly with people, and going to archives where that kind of coalition and solidarity already exists—has been really meaningful.

That sense of community really comes through in the grid of prints. One photo shows a Take Your Child to Work Day sign; others show hands gently on a patient’s body.

There’s this incredible series of photographs from the Iowa Women’s Archive, which is at the University of Iowa, and it’s from a clinic in Iowa City that donated all their material. There are tens and tens of pictures that almost appear to be massage. They’re so tender and extraordinary, and I’m so happy to have pictures of deep friendship and connection and support next to the pictures of answering the phone, next to the picture of Take Your Daughter to Work Day. It all feels like it’s of a piece.

The waiting rooms, too, caught my eye. Now, when we think about the word waiting in the context of abortion, it’s related to the ill-intentioned wait times that make procedures inconvenient or impossible. Here, waiting comes back to a more neutral space.

I’m thinking of one suite of pictures from Preterm, in Cleveland, which is the oldest abortion provider in Ohio and sort of where this project began. There are maybe 60 pictures that I’m assuming were made for educational purposes, and they show a woman who is [hypothetically] going through the process of getting a surgical abortion. It starts with her dialing the phone. Someone’s on the other end. She checks in. She waits in the waiting room. She looks through a magazine. She gets her blood taken. She gets fitted for a diaphragm. She waits in the waiting room after, and then she walks out. I just thought it was so poignant. I love what could be demonstrated and taught holistically through photographs.

It reminds me of how nurses prepare you for what’s ahead by saying, “This is going to be a little cold,” or “There’s going to be a little bit of pressure here.” Photography can do that too.

Almost better than reading or a written description. That’s the most head-on example because you see somebody walking through the steps. I’ve had an abortion—I’ve never seen that. You know what I mean? I came into that series early, and it was one of the things that made me feel like there’s a project here.

On the flip side, were there holes in the image archive that spurred you to make your own pictures?

The curator, Casey, was really the one who pushed me because I was visiting the clinics. I think I felt really nervous to insert myself or make myself a protagonist here, and one thing that Casey was continually reminding me was, “You’re in this, whether you like it or not. You’re collecting. You’re editorializing in some sense. And not only that, but your presence is important. You are talking about intergenerational exchange and inheritance. How does that become visible?” I feel so jazzed to be able to put those pictures of those women in a museum.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.