14th Gwangju Biennale review: a stage for new voices and ancient ideas

Wallpaper / Apr 12, 2023 / by Will Jennings / Go to Original

South Korea’s 14th Gwangju Biennale (until 9 July 2023) takes water as its central theme, in which climate, Daoism, historical trauma, local craft and voices of the marginalised float to the surface

A torrential downpour during the opening day of a major art event, with peak deluge falling as dignitaries and artists take to an outdoor stage for the ceremony, might normally be considered a disaster for organisers. Not so for the Gwangju Biennale. ‘After the drought of the last few weeks, this rain is a blessing’, said Park Yang-woo, president of Gwangju Biennale.

While perhaps annoying to the saturated attendees of Gwangju Biennale opening, especially those who stayed beyond the politics and platitudes to watch Lebanese artist Tarek Atoui perform new electroacoustic work Prelude to Rain, created – like much within this 14th edition – in collaboration with local makers and artists. ‘I feel very silly now,’ a soaked Atoui said after introducing the work, the rain having preluded many hours earlier.

14th Gwangju Biennale: Soft and Weak like Water

The weather was also curatorially fitting to the central theme of biennale artistic director Sook-Kyung Lee, moonlighting from her position as senior curator of International Art at Tate. Her overarching title Soft and Weak like Water references rain, flood, and climate, but is drawn from a Daoist principle concerning water’s ability to embrace contradiction and paradoxes. Lee’s curation centres on artists from global indigenous communities and practices which do not neatly fit into Western-centric classification systems, amplifying voices of the politically marginalised to be considered agents of social and planetary transformation.

79 individual artists and collectives pack four large galleries of the city’s Biennale building and four sites of historic and cultural importance across Gwangju, a city in southeast Korea with rich artistic and political histories. It was here, on 18 May 1980 that a citizens’ democratic uprising was opposed by military violence. The Gwangju Massacre, in which up to 2,300 died, left a legacy resonant throughout modern-day Korea. The curators here seek to not contain the events to regional status, but to explore them through global shadows of solidarity and progressive opposition.

This is present within a striking hang of woodcut-printed fabrics by Malaysian collective Pangrok Sulap, whose research into local political struggles and craftsmanship informed collaborative woodcarving and a series of stark renderings of resistance, recognition, and solidarity. Displayed in proximity to 1980s woodcut prints by Oh Yoon of the human body in acts of dance and labour, a poetic continuity of aesthetic and political awareness is present.

Nearby, work by two Gwangju artists of different generations speak to one another. Yu Juwon’s (b. 1983) Terminal Destiny is a gridded wall-maquette of urban development built for the biennale space, fragile in material but robust in its orthodox grid, critiquing ideas of the modernist reproducible unit to form a greater whole. Nearby, black ink works of Yeon-gyun Kang (b.1941) show a geometry seemingly holding more innate strength through informality and fluidity. Kang was present at the May 18 uprisings, their arrangements reading as psychological maps, diagrams, or a recognition of the strength of solidarity between different agents.

Considering water as more of a cyclical force than a capturable form, many works seek to solidify beyond the fixed or physical. A ritual from Mexico City-based Noé Martínez responds to his 11 ceramic sculptures and a hanging collection of ceramic amulets, invoking his 16th-century Huastec ancestors to the biennale, lives once trafficked by European colonisers. Martínez’s works symbolically bring those distant lives and their unlived potential into the place. Elsewhere, Oum Jeongsoon’s patchwork-covered sculptures read as abstract forms in fact are based on models of elephants created by visually impaired collaborators who draw on senses beyond sight to visualise the animal. The project which began at the city’s zoo, won the biennale’s Park-Seo-bo Art Prize of $100,000, the first of ten awards over the next two decades following a donation by the celebrated monochromatic painter. These are unique recreations of an unseen creature, formed by visually impaired collaborators then celebrated by the artist.

‘Water,’ the curator says, ‘can be slow moving, but shapes geographies over time.’ Works throughout also speak to this gradual but impactful flow, not just riparian but also cultural and social. Betty Muffler’s acrylic paintings on linen are psychological and physical mappings of sites of invisible healing energy across Australia’s Pitjantjatjara Country, while Judy Watson also evokes memory landscapes of the same country with a series of recent works made with natural materials found in the very watery landscapes she poetically maps.

New work by Robert Zhao Renhui continues his Critical Zoological gaze, re-forming a culverted Singapore river into an installation. Videos of wildlife in nearby spaces overlook an arrangement of found objects from the buried stream in a process of archiving and refreshing its many layers of life. Where Zhao Renhui’s stream is released from its manmade encasement, Abbas Akhavan creates an artificial looping watercourse. Using stones and pebbles from Gwangju he has created a short stream as a set piece framed by a greenscreen corner. This is a real stream, but the visible technology and structure behind the imported stones highlight the forced cycle and question the representation of nature.

This is not a biennale of the normal blue-chip artists airdropped into the global art festival circuit – and is the stronger for it. New voices and ancient ideas are both able to float to the surface in a confluence of thinking and practices which speak to ways of perceiving and working with human and non-human nature. Instead of dwelling upon the Gwangju massacre and its national importance, Sook-Kyung Lee and her curatorial team have used it to consider how it connects to other times and places, an exercise which can only forge more solidarity and planetary understanding.

Yu Jiwon, Terminable Destiny (2023); (Image credit: Courtesy the artist and Gwangju Biennale Foundation)

A torrential downpour during the opening day of a major art event, with peak deluge falling as dignitaries and artists take to an outdoor stage for the ceremony, might normally be considered a disaster for organisers. Not so for the Gwangju Biennale. ‘After the drought of the last few weeks, this rain is a blessing’, said Park Yang-woo, president of Gwangju Biennale.

While perhaps annoying to the saturated attendees of Gwangju Biennale opening, especially those who stayed beyond the politics and platitudes to watch Lebanese artist Tarek Atoui perform new electroacoustic work Prelude to Rain, created – like much within this 14th edition – in collaboration with local makers and artists. ‘I feel very silly now,’ a soaked Atoui said after introducing the work, the rain having preluded many hours earlier.

Mataaho Collective, Tuakirikiri (2023); (Image credit: Courtesy Mataaho Collective and Gwangju Biennale Foundation)

14th Gwangju Biennale: Soft and Weak like Water

The weather was also curatorially fitting to the central theme of biennale artistic director Sook-Kyung Lee, moonlighting from her position as senior curator of International Art at Tate. Her overarching title Soft and Weak like Water references rain, flood, and climate, but is drawn from a Daoist principle concerning water’s ability to embrace contradiction and paradoxes. Lee’s curation centres on artists from global indigenous communities and practices which do not neatly fit into Western-centric classification systems, amplifying voices of the politically marginalised to be considered agents of social and planetary transformation.

79 individual artists and collectives pack four large galleries of the city’s Biennale building and four sites of historic and cultural importance across Gwangju, a city in southeast Korea with rich artistic and political histories. It was here, on 18 May 1980 that a citizens’ democratic uprising was opposed by military violence. The Gwangju Massacre, in which up to 2,300 died, left a legacy resonant throughout modern-day Korea. The curators here seek to not contain the events to regional status, but to explore them through global shadows of solidarity and progressive opposition.

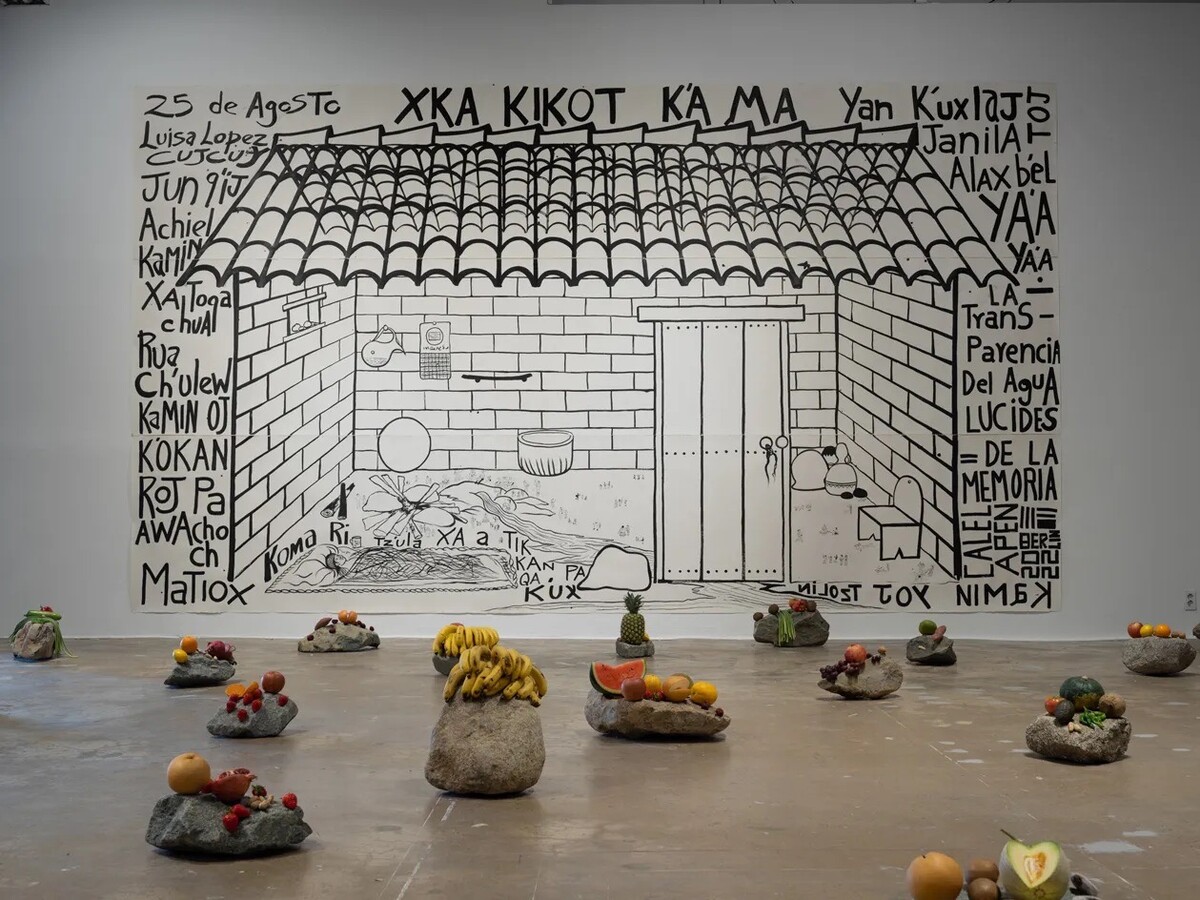

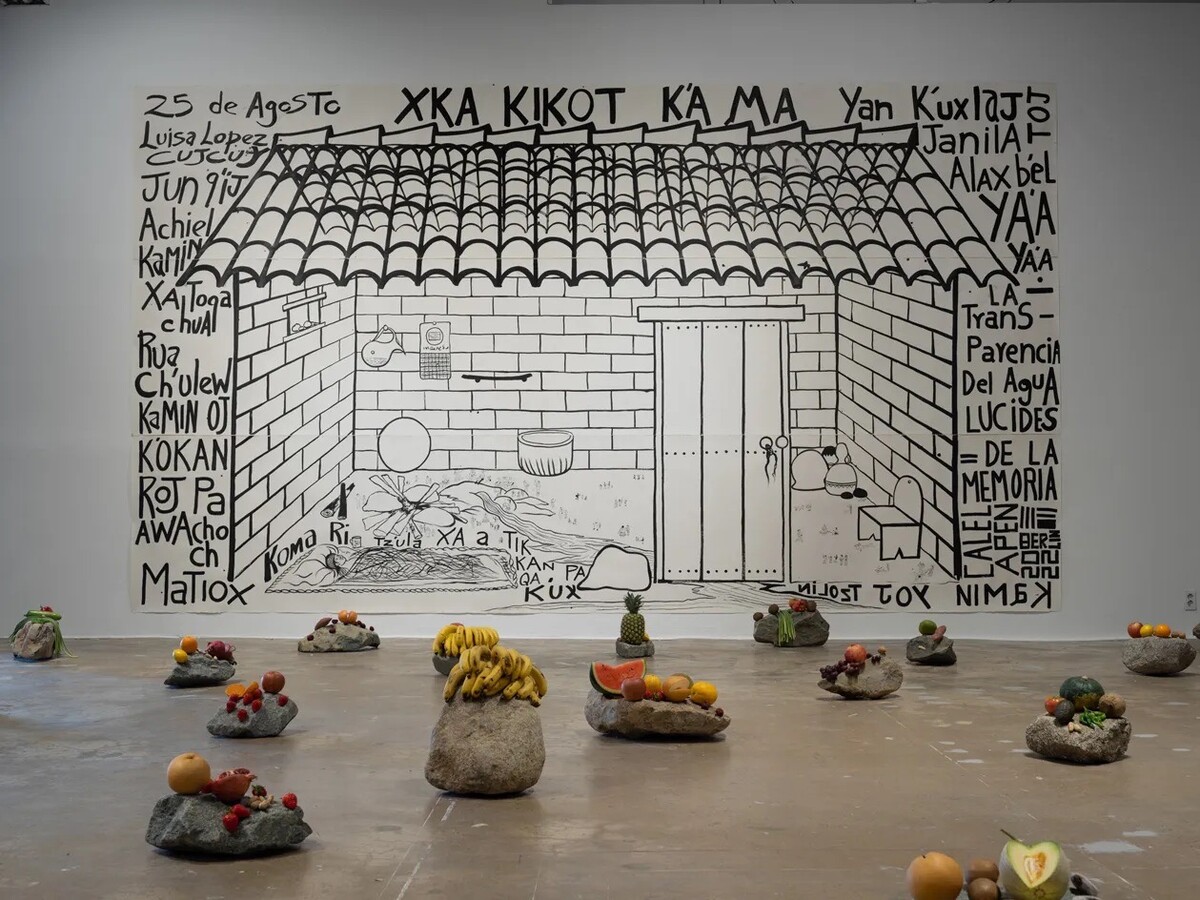

Edgar Calel, Installation view; (Image credit: Courtesy the artist and Gwangju Biennale Foundation)

This is present within a striking hang of woodcut-printed fabrics by Malaysian collective Pangrok Sulap, whose research into local political struggles and craftsmanship informed collaborative woodcarving and a series of stark renderings of resistance, recognition, and solidarity. Displayed in proximity to 1980s woodcut prints by Oh Yoon of the human body in acts of dance and labour, a poetic continuity of aesthetic and political awareness is present.

Nearby, work by two Gwangju artists of different generations speak to one another. Yu Juwon’s (b. 1983) Terminal Destiny is a gridded wall-maquette of urban development built for the biennale space, fragile in material but robust in its orthodox grid, critiquing ideas of the modernist reproducible unit to form a greater whole. Nearby, black ink works of Yeon-gyun Kang (b.1941) show a geometry seemingly holding more innate strength through informality and fluidity. Kang was present at the May 18 uprisings, their arrangements reading as psychological maps, diagrams, or a recognition of the strength of solidarity between different agents.

Noé Martínez, Bunch 3 (Racimo 3) (2022); (Image credit: Courtesy the artist and Gwangju Biennale Foundation)

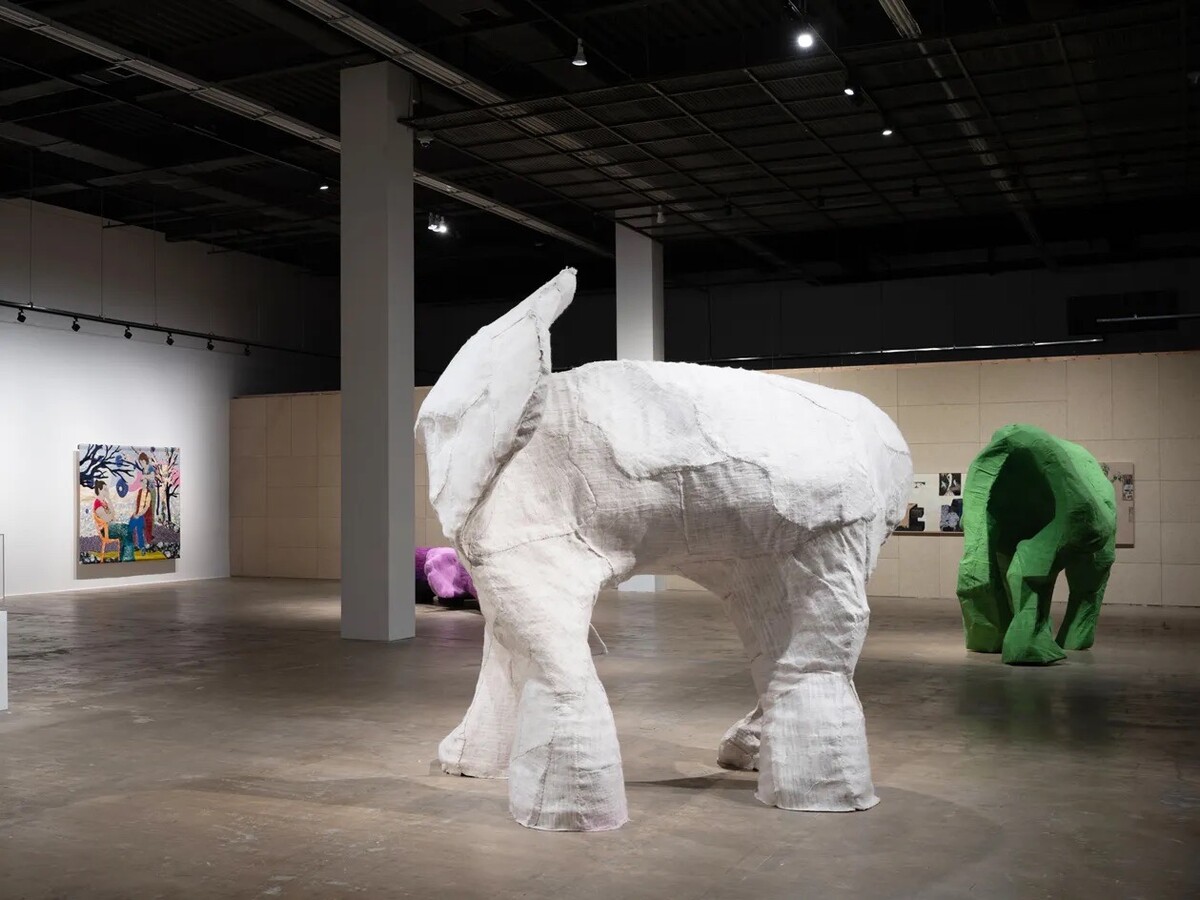

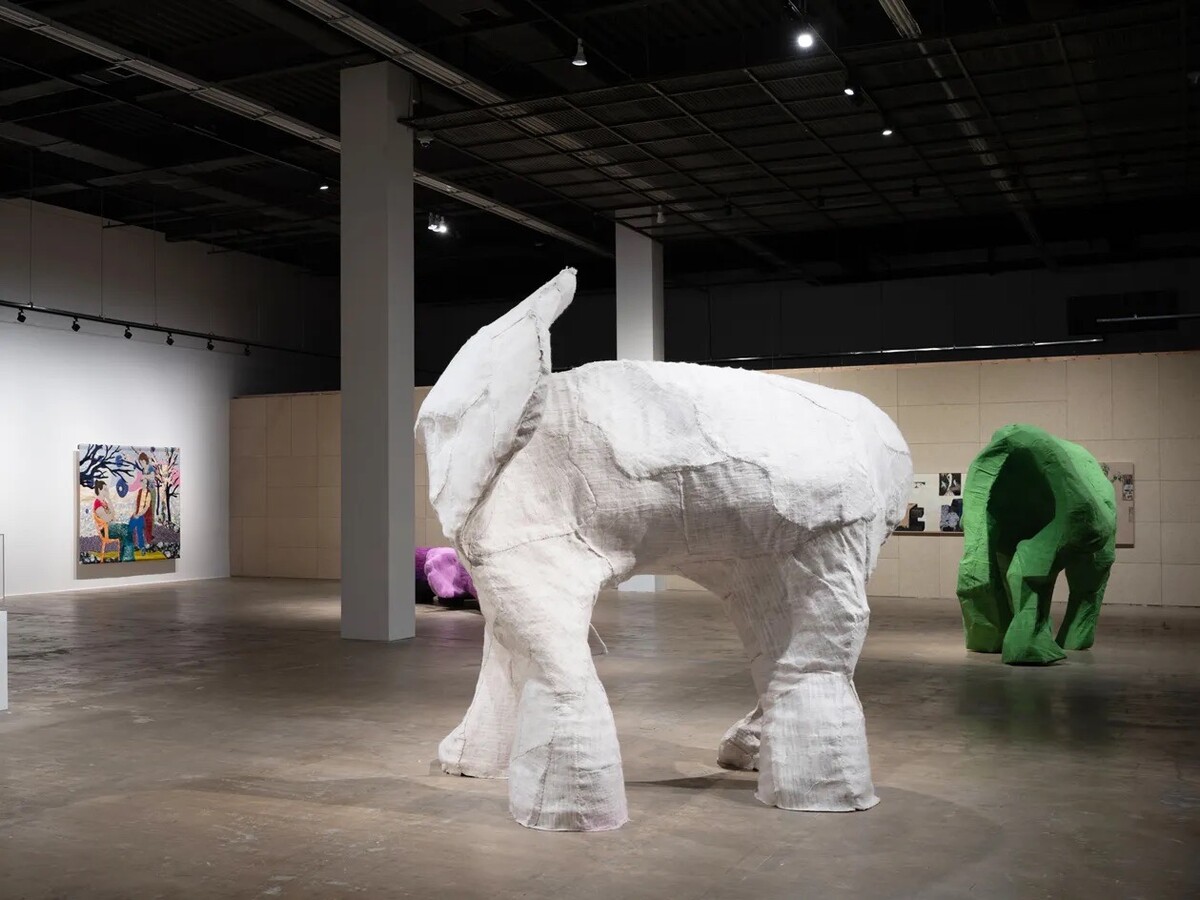

Considering water as more of a cyclical force than a capturable form, many works seek to solidify beyond the fixed or physical. A ritual from Mexico City-based Noé Martínez responds to his 11 ceramic sculptures and a hanging collection of ceramic amulets, invoking his 16th-century Huastec ancestors to the biennale, lives once trafficked by European colonisers. Martínez’s works symbolically bring those distant lives and their unlived potential into the place. Elsewhere, Oum Jeongsoon’s patchwork-covered sculptures read as abstract forms in fact are based on models of elephants created by visually impaired collaborators who draw on senses beyond sight to visualise the animal. The project which began at the city’s zoo, won the biennale’s Park-Seo-bo Art Prize of $100,000, the first of ten awards over the next two decades following a donation by the celebrated monochromatic painter. These are unique recreations of an unseen creature, formed by visually impaired collaborators then celebrated by the artist.

Oum Jeongsoon, Elephant without trunk (2023); (Image credit: Courtesy the artist and Gwangju Biennale Foundation)

‘Water,’ the curator says, ‘can be slow moving, but shapes geographies over time.’ Works throughout also speak to this gradual but impactful flow, not just riparian but also cultural and social. Betty Muffler’s acrylic paintings on linen are psychological and physical mappings of sites of invisible healing energy across Australia’s Pitjantjatjara Country, while Judy Watson also evokes memory landscapes of the same country with a series of recent works made with natural materials found in the very watery landscapes she poetically maps.

New work by Robert Zhao Renhui continues his Critical Zoological gaze, re-forming a culverted Singapore river into an installation. Videos of wildlife in nearby spaces overlook an arrangement of found objects from the buried stream in a process of archiving and refreshing its many layers of life. Where Zhao Renhui’s stream is released from its manmade encasement, Abbas Akhavan creates an artificial looping watercourse. Using stones and pebbles from Gwangju he has created a short stream as a set piece framed by a greenscreen corner. This is a real stream, but the visible technology and structure behind the imported stones highlight the forced cycle and question the representation of nature.

This is not a biennale of the normal blue-chip artists airdropped into the global art festival circuit – and is the stronger for it. New voices and ancient ideas are both able to float to the surface in a confluence of thinking and practices which speak to ways of perceiving and working with human and non-human nature. Instead of dwelling upon the Gwangju massacre and its national importance, Sook-Kyung Lee and her curatorial team have used it to consider how it connects to other times and places, an exercise which can only forge more solidarity and planetary understanding.