The Art World Has Never Fully Embraced Glass. Charisse Pearlina Weston Is Changing That

Cultured / Nov 27, 2023 / by Camille Okhio / Go to Original

The 34-year old artist finds conceptual meaning in the transparent material, exploring themes of Black interiority and resistance. Her practice is currently on view in “And Ever an Edge: Studio Museum Artists in Residence 2022-23” at MoMA PS1 and “In Common: New Approaches with Romare Bearden” at Parsons School of Design’s Sheila C. Johnson Design Center.

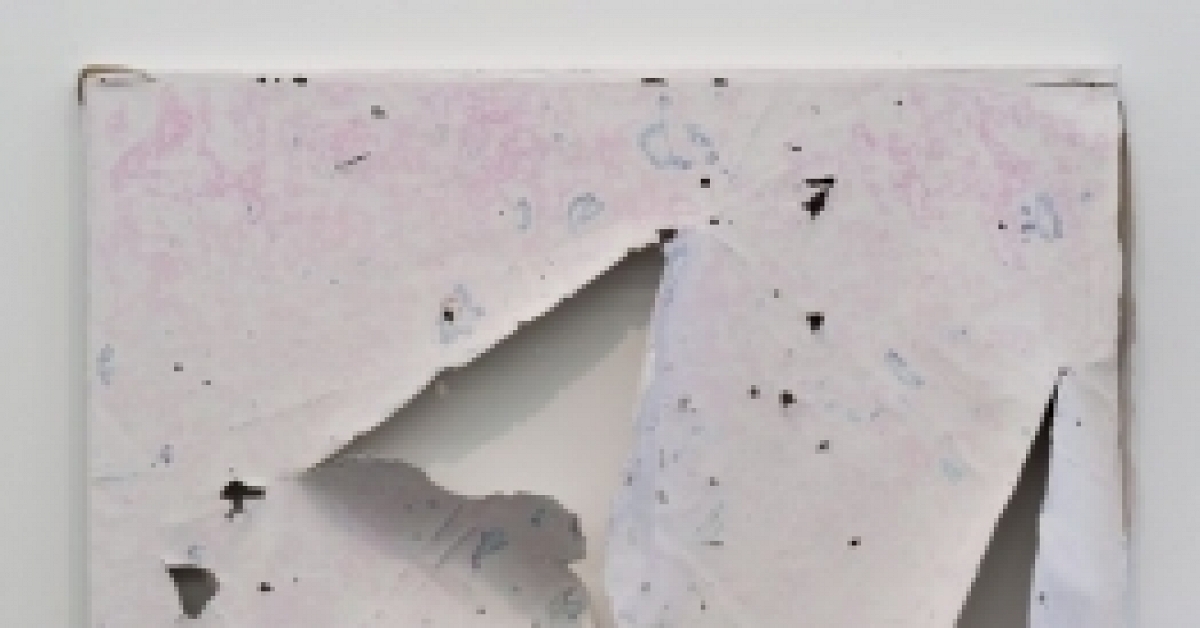

In its raw form, glass embodies conflicting states of existence: hard, soft, sharp, smooth. It can be stiff and unyielding, yet delicate enough to interact with the most sensitive sites: the mouth, the eye, the hand. Shattered, it slices and severs.

For Charisse Pearlina Weston, the material is a tool of resistance. Though synonymous with fragility and transparency, in her hands it becomes a means by which to obfuscate and protect. She molds it into a medium of refusal, a poem in physical form.

The New York–based artist first discovered glass in 2016 while searching for a way to layer text and photography. Her approach is straightforward: She relies mostly on slumping or hot-folding the material while it is in the kiln. “I have been painted as a glass artist, though I am not formally trained,” says Weston. “My interest in glass is as a conceptual vehicle.”

Glass is one of several mediums within the lexicons of sculpture and writing through which the 34-year-old explores Black intimacy, mourning, memory, and interiority. When she injects it with images and words (often poems or found quotes), it serves to highlight the manifold ways in which Black safety and belonging are consciously degraded. More specifically, Weston confronts police brutality, unsolicited interpersonal intervention, and the ways the Black body has been seized, used, and perceived nonconsensually.

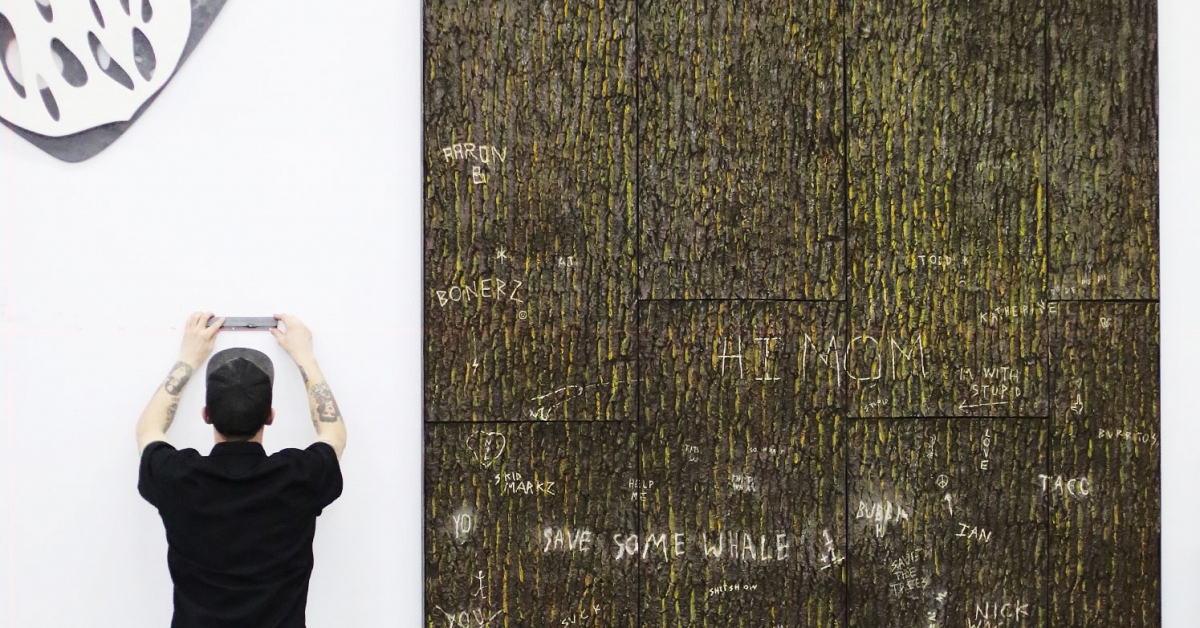

In “of [a] tomorrow: lighter than air, stronger than whiskey, cheaper than dust,” a solo exhibition at the Queens Museum last winter, Weston suspended a large artwork, of the same name as the show, from the ceiling of a central gallery. Its installation was foreboding, intentionally confusing the movement and bodily autonomy of visitors, forcing them to change course.

The work built on the gesture of defiance embodied by an unrealized resistance act proposed by the Brooklyn and Bronx chapters of the Congress of Racial Equality at the beginning of the 1964–65 World’s Fair, which was held where the museum now stands.

As she excavates the past through her work, Weston also sustains her momentum as a rising star in the conceptual art arena. With sculptural works included in an upcoming show at Museum Folkwang in Essen, Germany, and new work unveiling this fall at MoMA PS1, she is turning to other materials, like canvas, to interrogate and dismantle strategies of oppression, while maintaining her connection to glass.

Photos by Denzel Golatt

In its raw form, glass embodies conflicting states of existence: hard, soft, sharp, smooth. It can be stiff and unyielding, yet delicate enough to interact with the most sensitive sites: the mouth, the eye, the hand. Shattered, it slices and severs.

For Charisse Pearlina Weston, the material is a tool of resistance. Though synonymous with fragility and transparency, in her hands it becomes a means by which to obfuscate and protect. She molds it into a medium of refusal, a poem in physical form.

The New York–based artist first discovered glass in 2016 while searching for a way to layer text and photography. Her approach is straightforward: She relies mostly on slumping or hot-folding the material while it is in the kiln. “I have been painted as a glass artist, though I am not formally trained,” says Weston. “My interest in glass is as a conceptual vehicle.”

Glass is one of several mediums within the lexicons of sculpture and writing through which the 34-year-old explores Black intimacy, mourning, memory, and interiority. When she injects it with images and words (often poems or found quotes), it serves to highlight the manifold ways in which Black safety and belonging are consciously degraded. More specifically, Weston confronts police brutality, unsolicited interpersonal intervention, and the ways the Black body has been seized, used, and perceived nonconsensually.

In “of [a] tomorrow: lighter than air, stronger than whiskey, cheaper than dust,” a solo exhibition at the Queens Museum last winter, Weston suspended a large artwork, of the same name as the show, from the ceiling of a central gallery. Its installation was foreboding, intentionally confusing the movement and bodily autonomy of visitors, forcing them to change course.

The work built on the gesture of defiance embodied by an unrealized resistance act proposed by the Brooklyn and Bronx chapters of the Congress of Racial Equality at the beginning of the 1964–65 World’s Fair, which was held where the museum now stands.

As she excavates the past through her work, Weston also sustains her momentum as a rising star in the conceptual art arena. With sculptural works included in an upcoming show at Museum Folkwang in Essen, Germany, and new work unveiling this fall at MoMA PS1, she is turning to other materials, like canvas, to interrogate and dismantle strategies of oppression, while maintaining her connection to glass.

Photos by Denzel Golatt