Young voices from the Whitney Biennial: Urgent questions of minority identity propel this edition

Art Basel / Mar 23, 2024 / by Sarah P. Hanson / Go to Original

The Whitney’s 81st biennial exhibition, which opened to the public on March 20, features a notable number of suspended sculptures that cannot help but feel like metaphors for the historical moment. Climate change, racism, trans rights, bodily autonomy, war, artificial intelligence – ‘we’re at a precipice in so many ways,’ notes Iles, who co-curated the show with the museum’s curator-at-large, Meg Onli. The works ask visitors to navigate around them, and consider multiple vantages, subtly reinforcing the exhibition’s theme, ‘Even Better Than the Real Thing,’ in which notions of authenticity and subjectivity hang in the balance.

Thirty years on from the 1993 biennial, which famously thrust marginalized voices to the fore, the 71 artists and collectives in this edition seem bent on eluding categorization. ‘Something that became clear early on in our conversations with artists was their desire to challenge ideas of fixed identity,’ Onli observes in the catalog. ‘These artists want to destabilize the ways that identity gets flattened within the art world.’ Below, we highlight five works in the show that embody this mission.

Charisse Pearlina Weston, un- (anterior ellipse[s] as mangled container; or where edges meet to wedge and [un]moor), 2024. Collection of the artist. Courtesy PATRON gallery and Jack Shainman Gallery.

Charisse Pearlina Weston

un- (anterior ellipse[s] as mangled container; or where edges meet to wedge and [un]moor)

(2024)

In one corner of a fifth-floor gallery, a monumental, canted shelf of glass slices diagonally overhead. Made of panels of smoked glass hung from spindly cables, the installation, by the conceptual artist Charisse Pearlina Weston (b. 1988), casts a literal shadow over the proceedings, undercutting the transparency afforded by the museum’s floor-to-ceiling windows. It is an iteration of a work, which, when it was shown in a 2022-23 solo show at the Queens Museum, functioned as an obstruction that invoked the nonviolent 1960s civil rights protests near that site. Although simple in form, the installation is hardly inert; it is emblematic of what the curators identify as a potent strain of ‘refusal’ among Black artists today.

In recent sculptures that fold or stretch sheets of transparent glass, Weston (who is also a writer), seeks to deploy deploys the medium’s reflectivity, malleability, and fragility to poetic and metaphoric ends. Newly represented by Jack Shainman Gallery in New York and PATRON in Chicago, Weston (a native of Houston) will take part in The Chinati Foundation’s artist residency in Marfa, Texas, later this year.

Seba Calfuqueo, TRAY TRAY KO, 2022. Courtesy the artist, Galería Patricia Ready, Galeria Marilia Razuk, and LABOR.

Seba Calfuqueo

TRAY TRAY KO (2022)

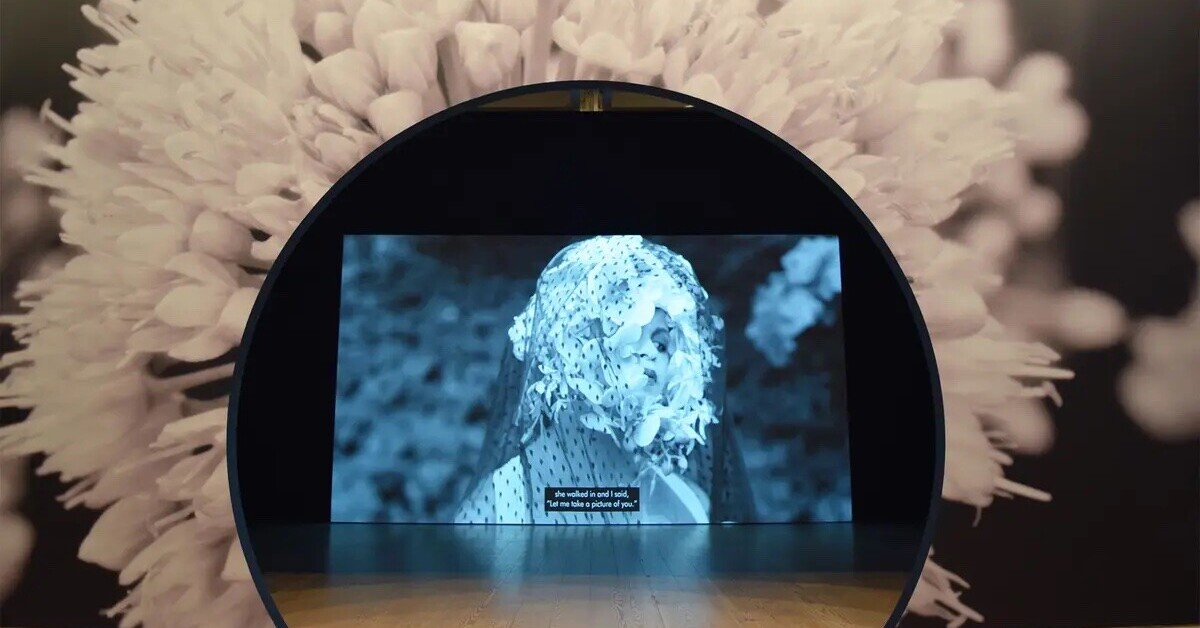

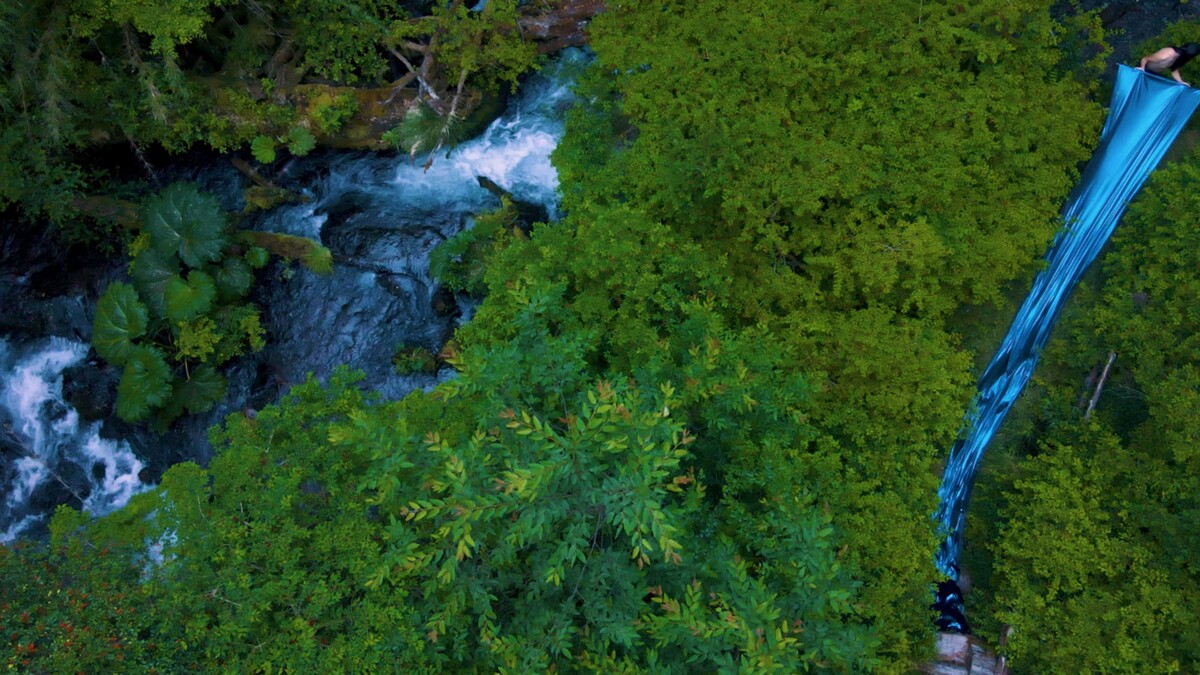

Even aside from this year’s expanded film program, video is a strong suit of the show, with contributions from Isaac Julien, Diane Severin Nguyen, Clarissa Tossin, and Tourmaline. One of the most absorbing is TRAY TRAY KO (2022), a 6-minute meditation by the Mapuche trans artist Seba Calfuqueo (b. 1991), who hails from Ngulumapu, in what is today known as Chile. In it, the artist – who is descended from the native Patagonians who resisted Spanish rule – drags a long, azure-colored cloth across a wooded landscape, eventually walking in parallel to a stream before arriving at a waterfall and proceeding with the cloth into the shimmering spray. Allusions to sacred ritual, Indigenous cosmologies, and queer symbology merge in a blend of performance and land art that dissolves into the sublime. According to María José Ovalle of the Santiago-based Galería Patricia Ready, the video attests to the ‘vital relationship between all species and people who inhabit the world.’ Calfuqueo, who does not restrict herself to any medium, is part of a chorus of pan-American Indigenous voices in contemporary art (also represented in this biennial by Rose B. Simpson, Demian DinéYazhi´, and others) that, despite their disparate regional origins, find common cause in practices that layer acts of decolonization with the retrieval of non-Western ways of knowing. Calfuqueo is also represented by Galeria Marilia Razuk in São Paulo and Labor in Mexico City, and will soon be seen in the upcoming ‘Foreigners Everywhere’ exhibition of the Venice Biennale.

Lotus L. Kang, In Cascades (2023). Co-commissioned by Chisenhale Gallery and the Contemporary Art Gallery In-kind production support for In Cascades was provided by Denniston Hill. Collection of the artist. Courtesy Franz Kaka.

Lotus L. Kang

In Cascades (2023)

A number of artists play with ideas of the body without directly invoking it. This sometimes takes the form of organic-technological hybrids or unstable materials, as is the case with In Cascades (2023), a large installation by Lotus L. Kang (b. 1985, Toronto). Jointly commissioned by London’s Chisenhale Gallery and Vancouver’s Contemporary Art Gallery, the main element consists of large furls of unfixed photographic film that the artist has exposed to light in varying treatments – using the environment to ‘tan’ these ‘skins’ like animal hides – then hung vertically like curtains in a staggered pattern that suggests a ‘ghostly architecture,’ as she puts it. Tatami mats and clusters of small sculptures hinting at memory and heritage (lotus root, anchovies) slide in perpendicularly from the floor.

Part of a dialogue with other works in the show that are designed to degrade over the course of the show, Kang’s mutable installation foregrounds porosity and its generative capacity. ‘When I work with modular materials, there’s an inheritance of migration, of make-do,’ she notes. ‘I’m interested in this idea of betrayal of form and what other meanings can come out.’ In addition to Toronto’s Franz Kaka gallery, Kang has joined the roster at Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles, where her work is included in the group exhibition ‘Familial Technologies’ through April 27.

Cannupa Hanska Luger, Uŋziwoslal Wašičuta (from the series Future Ancestral Technologies), 2021–.Collection of the artist. Courtesy Garth Greenan Gallery.

Cannupa Hanska Luger

Uŋziwoslal Wašičuta (from the series Future Ancestral Technologies) (2021-)

‘Technology’ is often framed in terms of digital advancement. But in the hands of Cannupa Hanska Luger (b. 1979), a member of the Three Affiliated Tribes of Fort Berthold in present-day North Dakota, technology equals ancient wisdom. In 2018, Luger, who shows with Garth Greenan Gallery in New York, embarked on a series of ‘Future Ancestral Technologies’ that he describes as ‘Indigenous science fiction… a way of future dreaming rooted in continuum.’ The shape this takes at the Whitney is a fuchsia, black, and orange mesh cone suspended from the ceiling and anchored to the floor with small fin-like metal sculptures. Originally created for the Albuquerque Museum, it is an inverted tipi, the shelter of the nomadic peoples of the Plains, rendered here not as a structure to enter or inhabit but rather as a portal to a pre-capitalist, pre-colonial past. In the loaded context of museums, which have long objectified stolen and sacred Indigenous items, Luger is careful to deny full access. But using the tipi as a tool to invert our worldview, he points the way toward a potential liberation.

Takako Yamaguchi, Issue, 2023. Collection of the artist. Courtesy Ortuzar Projects, and as-is.la.

Takako Yamaguchi

Issue (2023); Proxy (2022); Catalyst (2023); Formula (2023); and Clasp (2022)

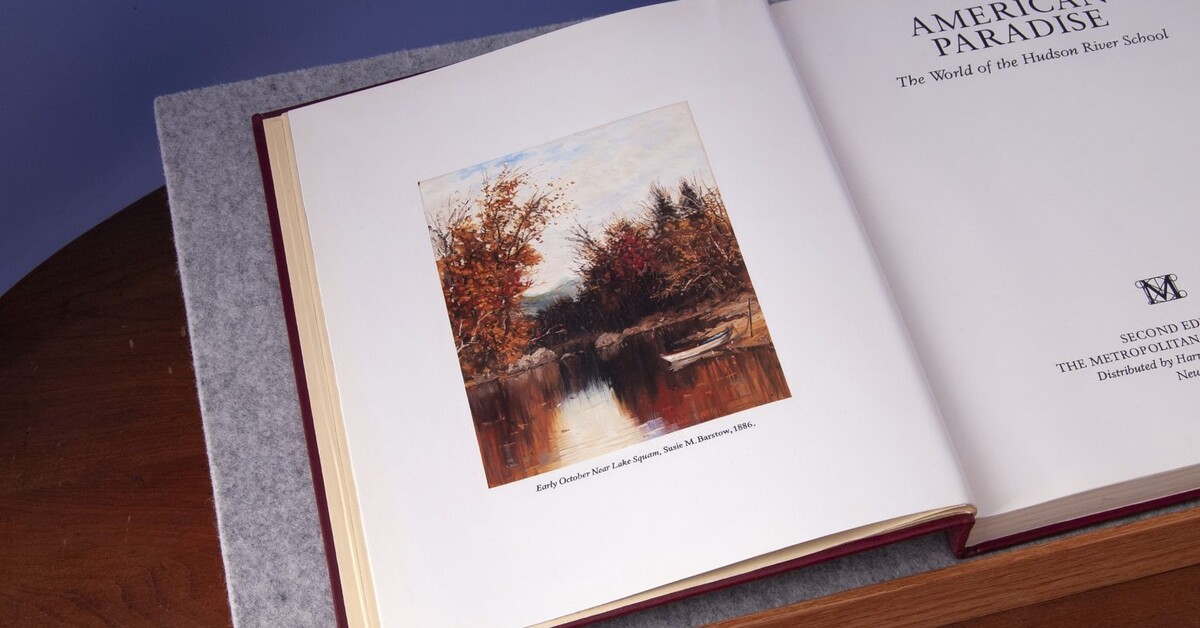

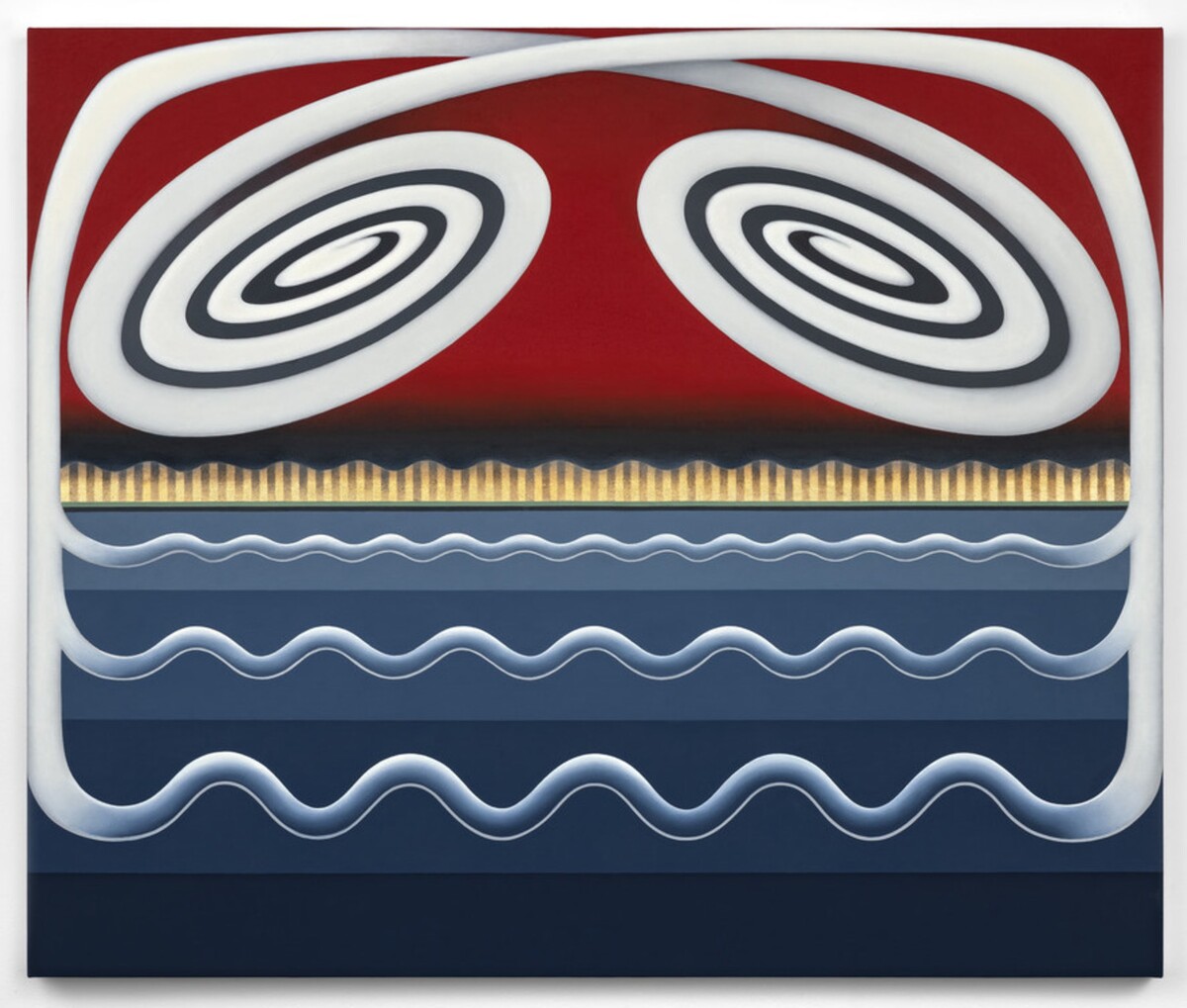

Painters are in relatively scarce supply in this biennial, but the curators make their inclusions count, particularly by highlighting a handful of non-white women artists who have been working steadily against the grain for years. Take energetic, quasi-narrative abstractions by Mary Lovelace O’Neal (b. 1942), or the stylized architectures of Mavis Pusey (1928-2019). Or the Los Angeles-based painter Takako Yamaguchi (b. 1952), who contributed five recent canvases to the show, all of which build on her long interest in landscape and what she calls ‘abstraction in reverse’: a sly embedding of ornament in otherwise graphic, minimal compositions.

The seductively surfaced paintings on view transmute the drama of Romantic seascapes via Art Nouveau-inspired framing and suggestively modeled shapes. ‘She’s always looking at what falls out of art history,’ says Kenta Murakami, director at her New York gallery, Ortuzar Projects, pointing to previous series that have dealt with the female nude and photorealism (Yamaguchi also shows with as-is.la, where some of these works are currently on view through March 30). Like many young painters today, ‘she is interested in the superficial and invested in pleasure,’ says Murakami. ‘But simultaneously, she’s approaching each series with a certain level of critical distance, even irony.’ Yamaguchi leapfrogs binaries of identity and genre to arrive at a distinctive and sophisticated fusion – a trait that may be this biennial’s hallmark.