Unearthing the Roots of Colonialism: A Review of Noé Martínez at Patron Gallery

Newcity Art / Jul 23, 2024 / by Zara Yost / Go to Original

Noé Martínez, “Calmecayo, Abril 2024,” 2024, oil on copper, 7″ × 5 1/2″/Photo: Patron Gallery

Cotton tapestries with aquamarine acrylic paint and 22-karat gold leaf, sgraffito ceramics inlaid with obsidian and thread mimic ancient Tancol anthropomorphic vessels, copper as canvas paintings—some with brass inlays—and a short documentary film, “La cicatriz del Bosque 1, Curación,” occupy the exhibition space for Noé Martínez’s second solo show at Patron, “Las raíces conversan por debajo de la tierra,” which translates to, the roots talk beneath the earth.

Following the performance, “viento aparente, viento real” on June 4—in conjunction with the “Trade Windings: De-Lineating the American Tropics” exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, on view until December 1—Mexico City artist Noé Martínez uses symbolic materials like crystals, silver, fabrics and ceramic vessels to address, investigate and bring attention to his Huastecan raíces and ancestry. Unearthing the systemic roots of colonialism in his practice has become a central focus for Martínez, examining colonialism in two parts. One is the global context, an economic process distributed throughout countries today to “underdeveloped” areas or populations, and how organized nations gained political and legislative power economically and epistemologically over those cultures and peoples—his culture, his people—for centuries. The second is the colonization of the mind, body and spirit of those peoples. The Spanish and other colonizing nations wielded power and genocide over the Huastecs to create a mono culture, a mono economy and a mono agriculture. A colonialism that taught the Huastecs how to see, think, feel and reproduce a specific kind of culture, indoctrinating them and others into thinking that was the only way to live.

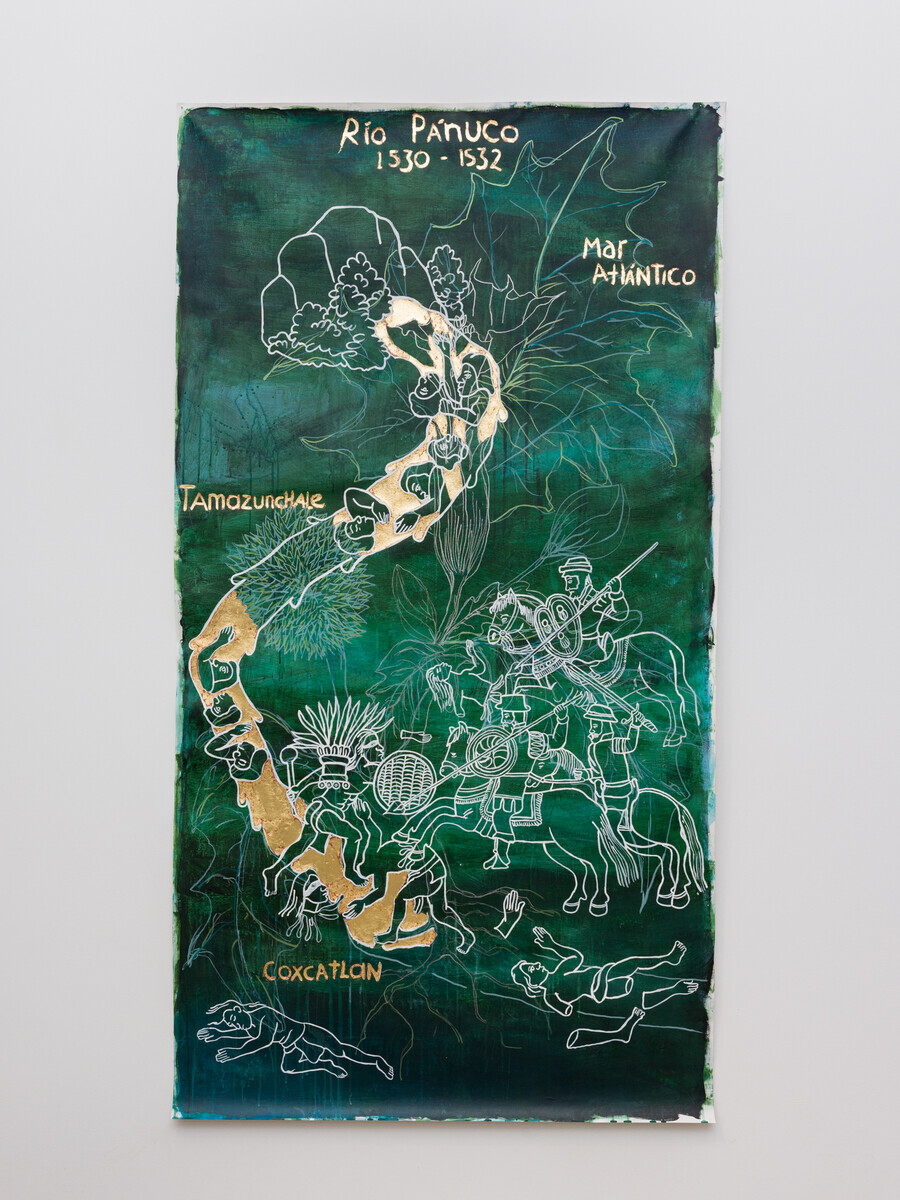

Noé Martínez, “Usaron el rio Pánuco para comenzar el genocidio,” 2024, acrylic on primed cotton fabric and 22-karat gold leaf, 82″ × 43 1/4″/Photo: Patron Gallery

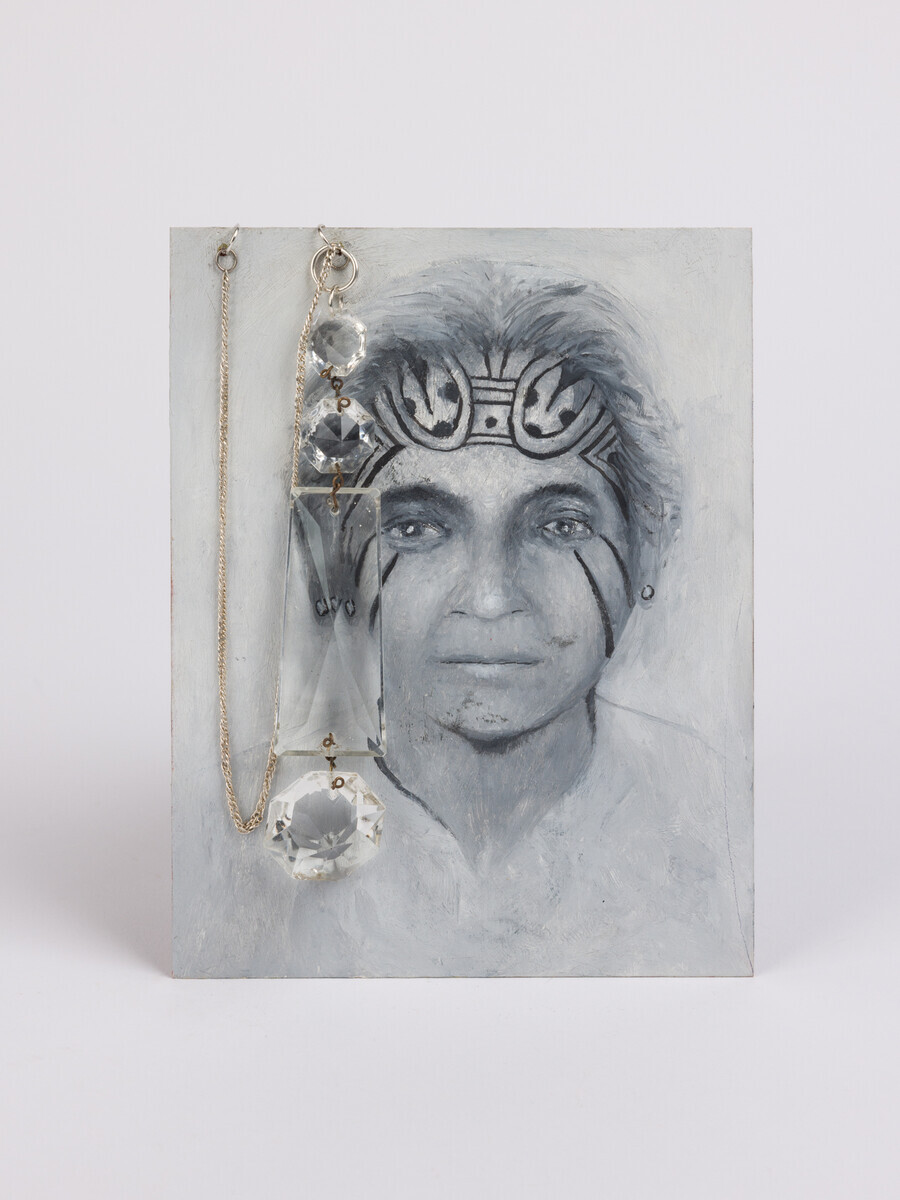

Oil on copper, a popular European method of painting in the sixteenth and seventeenth century, is employed by Martínez in order to honor and reclaim the painting practice by memorializing his grandmother and paternal aunt in, “Calmecayo, Abril 2024,” and, “Calmecayo, Enero 2007.” The matriarchal figures are painted diaphanously in black and white with their traditional Huastecan facial tattoos. Crystals drape over the apparitional portraits evoking sacerdotal embodiment. Like nutrients passing back and forth from the flesh and stones, it’s a transference of energy and minerals.

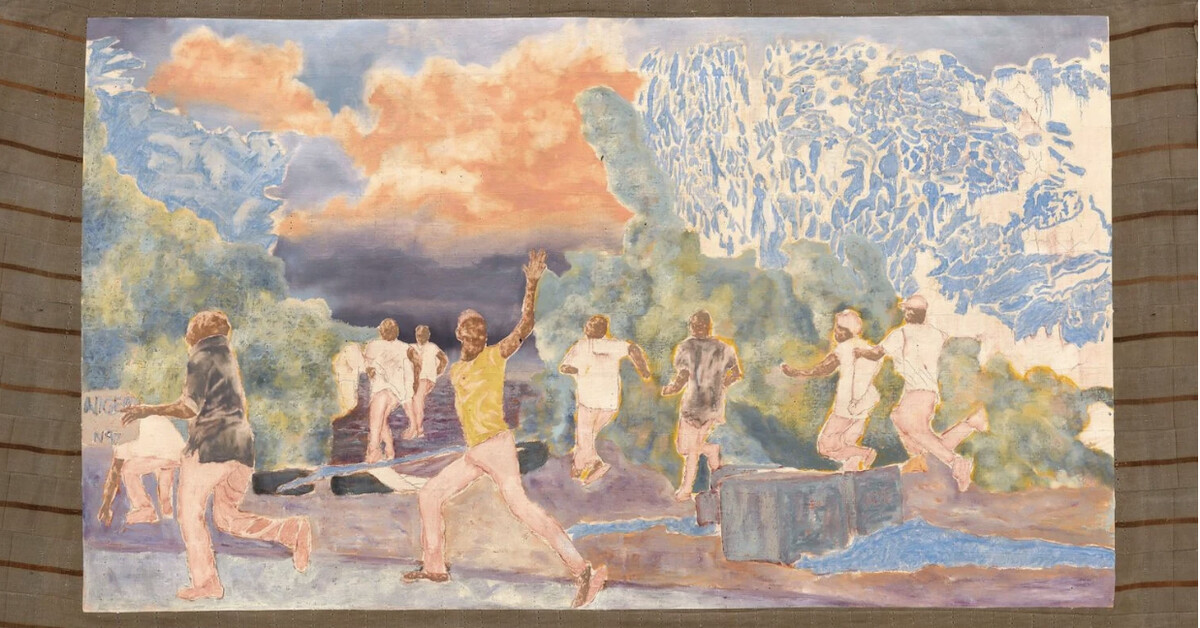

In his stela-style fabric paintings: “Usaron el rio Pánuco para comenzar el genocidio” (They used the Pánuco River to start the genocide), “Los esclavos fueron llevados al Caribe” (The slaves were taken to the Caribbean) and “Fueron traficados en barcos al caribe desde 1529” (They were trafficked on ships to the Caribbean since 1529), Martínez calls out the genocidal actions of the conquerors. In Mexican history, there’s a huge historical disparity, one that hasn’t considered, questioned or acknowledged slavery as an injustice against indigeneity, especially at the end of the sixteenth century—the beginning of the colonial period. The intra-generational atrocities committed against the Huastecan people haven’t been recognized, let alone healed.

Noé Martínez, “Huracán debajo de la tierra,” 2024, sgraffito high-temperature ceramic and thread, 11″ × 8″ × 7″/Photo: Patron Gallery

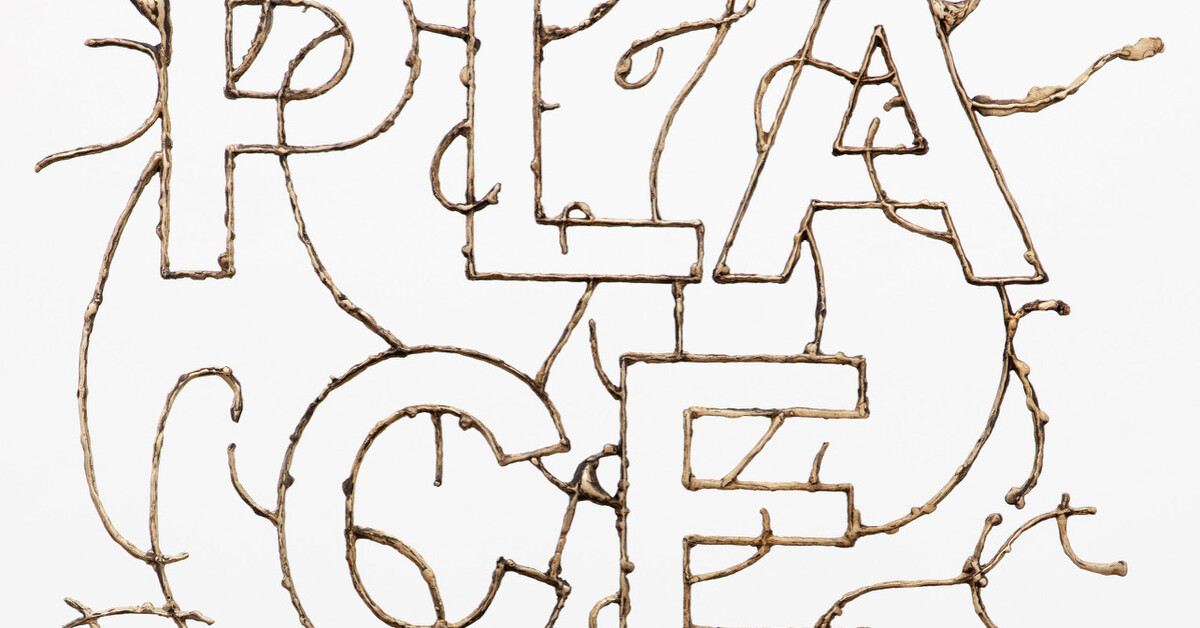

Martínez unequivocally pursues both acknowledgment and healing. The exhibition title, “Las raíces conversan por debajo de la tierra” (The roots talk beneath the earth) is a double entendre—the roots, and the routes talk beneath the earth. Martínez’s body of work encompasses the colonial trade routes that were inaugurated in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries by different European, colonial influences and particularly the migratory reality we are all engaging with both in reality and in a more theoretical, spiritual sense.

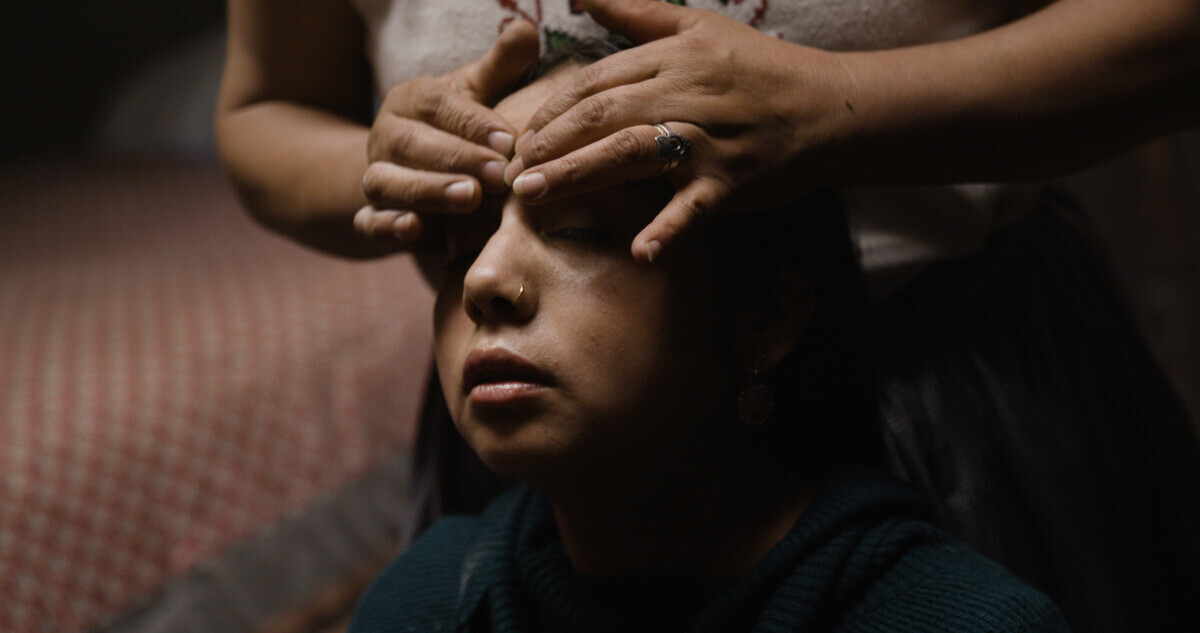

Martínez hones in on how these routes are being projected into the present, and the aftermath of how the products and bodies move about the world. He seeks to heal himself, and his people. The documentary shown in the gallery, “La cicatriz del Bosque 1, Curación” (The Forest Scar 1, Healing) shows us two individuals undergoing a healing ritual from Nana Ade, a curandera trained in healing ceremonies and indigenous rituals.

Noé Martínez, still from “La cicatriz del Bosque 1, Curación,” 2024, 4K color video, stereo sound, 37 min/Photo: Patron Gallery

In a rich narrative, we listen to how Rosi Huaroco and Giovanni Fabian witnessed an attack on the Cherán community in 2012 when armed illegal loggers intimidated the community and invaded their homes and land. Even after five-hundred years, the indigenous are still experiencing cultural, economic and social consequences because of injustices. The fear and the distress is acknowledged by Nana Ade as she concocts herbs and spiritual rituals to aid the two victims in releasing their traumas.

Martínez believes that spirits can enter and leave at different moments in time in the lives or in the past of people, and that he plays a part in being one of the beings that can be in several spaces in order to track down a pain, a worry or a dream. Along with the account in the film, Martínez has recorded a spirit dance in the woods, one that plants an eerie and sacred seed in me, as I’m sure it will in you.

Noé Martínez’s “Las raíces conversan por debajo de la tierra” is on view at Patron gallery, 1612 West Chicago, through August 17.