The art that’s found when other art gets erased, from Marvel to ‘The Odyssey’

The Chicago Tribune / Oct 2, 2018 / by Christopher Borrelli / Go to Original

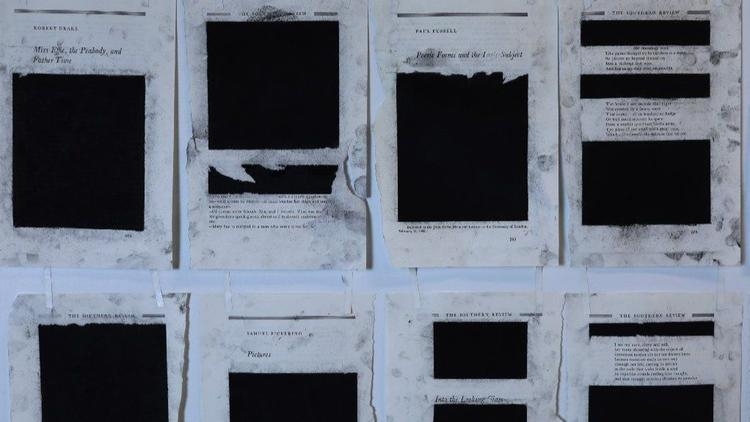

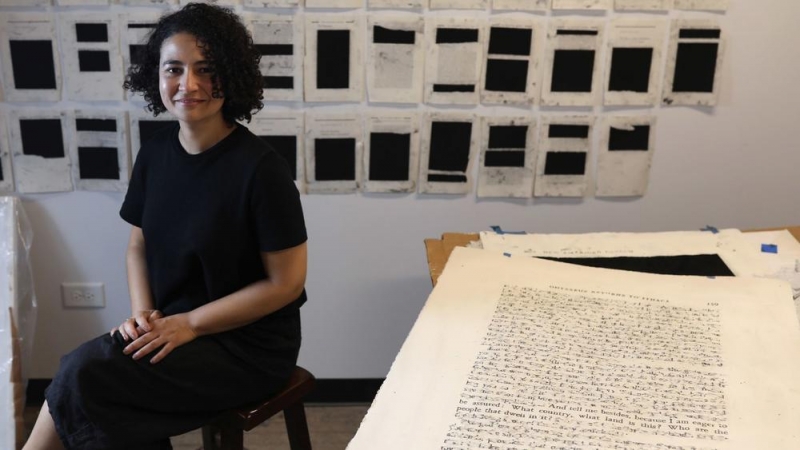

Bethany Collins stood in the middle of the gallery, gesturing at three long off-white paintings. Each had been smeared from top to bottom; nearly every stroke was smudged.

‚ÄúIt‚Äôs my spit,” she explained.

Each piece was a replica of a page from Homer‚Äôs ‚ÄúOdyssey,” each work a different translation of the same passage. Collins had copied the pages onto canvases, perfecting every curve of every font, capturing the width of every space and margin; she re-created the pages exactly, only larger. Then, when finished, she spit on them, smudging lines until the passages became illegible streaks.

Water would have worked, she said, but saliva is more acidic ‚Äî it leaves a texture, a residue. ‚ÄúAnd the residue of language,” she said with a smile, ‚Äúthat‚Äôs kind of become my thing.”

From a distance, the paintings are abstractions, blurry and amorphous. Move closer, you pick up fragments of lettering beneath the smudges, serifs and bits of typography that resemble fractured hieroglyphics of an extraterrestrial civilization. Closer still, you realize: Oh, wait, no, that is English, she’s just erased every trace of comprehension.

‚ÄúEverything,” Collins said, ‚Äúbut words I want you to read.”

Indeed, tucked amid smudges, hard to see, are sentences, not originally sequential, brought together now through erasure. All that remained on one painting, separated by long crossed-out bits, was: ‚ÄúWhat land is this? What people? What men are born here?”

‚ÄúIt‚Äôs from the part of Book 13 where Odysseus returns to his homeland,” she said, ‚ÄúAnd everything about his country looks familiar, and yet it all feels somehow strange now. When I read that, I thought, ‚ÄòThat sounds a lot like the political moment in this country.”

Collins, a rising conceptual artist who has been based in Chicago for the past couple of years, is among the savviest practitioners of erasure, a technique typically associated with visual arts and poetry in which an artist creates absence, often removing pieces from another, completed work. In both cases, the result is a creative act of destruction ‚Äî ‚Äúan additive subtraction,” as artist Jasper Johns once described erasure. Depending on your vantage, it also looks like an act of revelation, censorship, appropriation or plain-old artistic revenge. The endgame, though, is the same: picking away at a text to find the art beneath the art, showing another meaning or reading that had been waiting there all along, revealing how a set of words can mean different things to different people.

Collins‚Äô new show ‚Äî at the Patron Gallery in West Town through Oct. 28 ‚Äî is titled ‚ÄúUndersong” and features three sets of works: the ‚ÄúOdyssey” pieces; a series of classified ads once placed in 19th-century black newspapers by former slaves looking for the family they had been separated from; and paintings of patriotic American songs, including ‚ÄúAmerica the Beautiful” and ‚ÄúMy Country, ‚ÄôTis of Thee.” The ‚ÄúOdyssey” paintings, she said, ‚Äúfelt like the story we tell about ourselves, the classified ads felt like the actual story of who we are, and the songs, those are like a vision of a future that could be ‚Äî yet probably never will really be, because of course, the future is always us.”

Disparate as it sounds, what binds the show — other than being conceived, like so much of contemporary art now, as a response to Donald Trump’s presidency — is a fascination with the malleableness of words, and a paradoxical urge to erase most of those words.

From a distance, the song paintings look like constellations, snowflakes, feathers; the ads look like simple, monochromatic sheets of paper. Closer, you see the ads are stripped of printed type but rather imprints of type; and the song paintings are full of smudges, with phrases and words redrawn over and over, into knotty, abstracted swirls.

‚ÄúMy work often deals with language and race,” Collins said, ‚Äúand since I find language frustrating, erasure works well here. I want you to be frustrated ‚Äî not with the work but with trying to read it. (Erasure) makes me feel I can control a text that feels out of my hands. By the time I have written something a thousand times, or spit and erased a ton of sentences, I feel a physical mastering of language. By deciding what‚Äôs legible, I‚Äôm dragging out the meaning already there. Erasure, for me, means a nice sharp elbow.”

Call it blackout art.

Call it redaction poetry.

The act of subtracting from pre-existing work is an old tradition — at least as old as Duchamp and the ready-made conceptual provocations of the early 20th century. To varying degrees, erasure is found in both John Cage’s landmark silent performances for piano, and in the latest Avengers movie, which (spoiler!) erased half the Marvel Universe in a stroke. And yet, the 21st-century era of fake news, say-nothing congressional testimonies and Orwellian double-speak masquerading as official federal policy appears to have been tailor-made for erasure, providing fresh life to the genre.

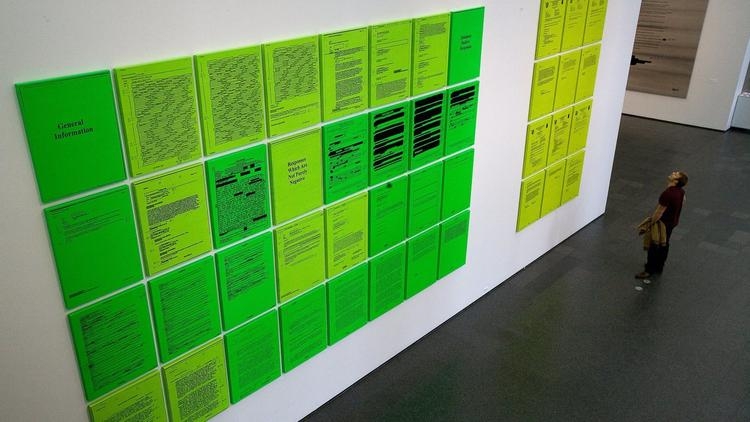

Documents as official as immigration and naturalization papers, Trump‚Äôs inauguration speech and the 9/11 Commission report have been squeezed of jargon and given new poignancy. Jenny Holzer‚Äôs 2006 ‚ÄúRedaction Paintings” found its canvases through the Freedom of Information Act ‚Äî Colin Powell memos, Iraqi prisoner statements, other Bush-era officialese ‚Äî at times redacting official redactions with Rothko-like blocks of color. More recently, poet Isobel O‚ÄôHare used erasure to edit the apology letters of disgraced men outed by the #MeToo movement.

Aesthetic acts of erasure are accessible and satisfying, said Chicago writer Alison Thumel. ‚ÄúThere is a feeling these erasures are uncovering what is really being said.”

At the University of Chicago, she studied with poet Srikanth Reddy, whose 2011 book ‚ÄúVoyager” was centered around an erasure of the memoirs of Austrian President (and Nazi intelligence officer) Kurt Waldheim. Last year, on The Rumpus, she published a series of erasure poems derived from articles she found on the right-wing Breitbart news site. She also published ‚ÄúLIFE OF,” a collection of poetry that draws from an erasure of ‚ÄúThe Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up,” Marie Kondo‚Äôs 2014 self-help best-seller.

She started a year after death in her family.

‚ÄúKondo notes if an object doesn‚Äôt ‚Äòspark joy‚Äô you must let it go,” she wrote in an email. ‚ÄúIn the midst of my grief, I was struggling to write. At the same time I was wondering what to do with my grief and certain objects I inherited. Those objects and feelings didn‚Äôt spark joy, yet I couldn‚Äôt get rid of them. I worked my way through the book beginning to end, eliminating Kondo‚Äôs words and trying to find my own ‚Äî in a way using the language of tidying to carve out language for my grief I had not been able to find before.”

Erasure work often begins with more classical, meaty text, like ‚ÄúParadise Lost” or Shakespeare‚Äôs sonnets. Baltimore artist Jenni. B. Baker, among the most prolific practitioners of erasure, has picked away at both David Foster Wallace‚Äôs ‚ÄúInfinite Jest” and a 1965 edition of the handbook of the Boy Scouts of America; she told the Michigan Quarterly Review that erasure ‚Äúallows me to commune with original text and author in a way that a work that was simply ‚Äòinspired by‚Äô or ‚Äòdedicated to‚Äô wouldn‚Äôt.”

Novelist Jonathan Safran Foer‚Äôs ‚ÄúTree of Codes” from 2010 is actually the 1934 book ‚ÄúStreet of Crocodiles” by Polish writer Bruno Schulz, stripped to a new work; Schulz was murdered by Nazis, leaving a void where there was a promise of greatness.

Indeed, because a work of erasure tends to contain both the original work and the revised work, still showing every scissored-out section and redacted sentence, the line between experimental poetry and a traditional work of visual art often gets a little fuzzy.

That said, the most famous act of erasure is arguably Robert Rauschenberg‚Äôs 1953 work ‚ÄúErased de Kooning Drawing.” It is exactly that. Rauschenberg wanted to know what happens to a work after it has been literally voided. He considered erasing some of his own work but decided the action wouldn‚Äôt contain the same provocation. So he asked de Kooning, a celebrated master of abstract expressionism at the top of his game then, to donate a work. Rauschenberg is said to have spent a month, and dozens of erasers, destroying the de Kooning. The finished piece (framed and labeled by Jasper Johns), still raises many of the issues and questions attached to the erasure genre:

Can we see beneath the damage?

Was it erased out of protest? Humor? Jealousy?

And what to make of this ‚Äî no act of erasure is complete. There‚Äôs always a stain or shadow left behind, a reminder of the material, flaked and hanging. In ‚ÄúChalk: The Art and Erasure of Cy Twombly,” the forthcoming biography of an artist whose work was often noted for containing the scribbled-over, illegible remains of his handwriting, author Joshua Rivkin writes: ‚ÄúThis is the magic (and poison) of these pieces, the sense that there‚Äôs a secret below, some nearly absent idea ‚Ķ humming its mystery.”

In the back of the Patron Gallery, Collins points to a small red hymnal she made. She filled the book with 100 different versions of ‚ÄúMy Country ‚ÄôTis of Thee” ‚Äî most culled from 19th and 20th centuries, and lyrically reworked by the Temperance Movement and the Confederacy and scores of other causes ‚Äî ‚Äúthen I lasered out all of the music notes, which was the only cohesive part of the book. So what‚Äôs left are just a lot of differences.”

And a slight acrid smell of burned paper.

And bits of lasered paper ‚Äî ‚Äúthe dust of language,” she says.

Collins grew up in Alabama and bounced around artist residencies before working with the artist Theaster Gates and settling in Chicago. She doesn‚Äôt bill herself exactly as an erasure artist, but she received her first serious attention about a decade ago for pieces made on chalkboards, using somewhat racist, condescending language she remembered receiving during her art school critiques, now blurred and copied into abstraction. For a 2014 Studio Museum residency in Harlem, she spent a year erasing all mention of color from a Webster‚Äôs New World College Dictionary to create a ‚ÄúColorblind Dictionary” ‚Äî as you turned pages, eraser shavings and paper shards tumbled free.

‚ÄúSomeone (told) me some of my erasure looks ‚Äòaggressive,‚Äô” she said, ‚Äúbut it doesn‚Äôt feel that way to me ‚Äî it feels like there was a problem with language and I tried to meet it.”

At the far end of the gallery, behind the administration desk, occupying one entire wall are 91 sheets of paper, which Collins has embossed a solid white and hung in tight, orderly rows. The pages contain the U.S. Department of Justice report on the Ferguson Police Department, issued after the 2014 shooting of an unarmed black teenager by a white officer. Collins soaked the pages and ran them through a process that raised type but removed actual print, leaving a ghost of the words. To read it, stand very close.

But don’t read it.

Collins intentionally left out the DOJ conclusion. ‚ÄúI‚Äôm not sure it counts exactly as erasure,” she said. ‚ÄúText is there. But so is an absence. I think of it as printing a lot of nothing. There are 91 pages of words hanging on this wall, and it‚Äôs still not enough.”