Kaveri Raina, Chapter NY

Artforum / Feb 1, 2023 / by Ara Osterweil / Go to Original

Corporeal forms and abstract shapes collide on unprimed, earthen fields in Kaveri Raina’s breathtaking paintings. The first time I saw them, in a 2019 group show at New York’s Luhring Augustine, their intense hues stopped me in my tracks. Reencountering her work in this solo show, I was struck anew by the augmented feeling in their forms. Created under the duress caused by the Trump presidency and the pandemic, her images transmit a combustive energy. No wonder Raina has analogized their affect to a heating kettle right before it screams.

In an era in which artworks often sacrifice passion for polish, abstraction rarely feels so urgent. Inspired by historical anticolonial resistance and the ongoing struggle against patriarchal oppression, Raina’s most recent canvases are both haunted by femicide and infused with the spirit of feminist resistance. While painting, the artist became fixated on the horrifying death of twenty-three-year-old Jyoti Singh (1989–2012), who was riding a bus in New Delhi when attacked by a group of men, who raped and murdered her. The incident and subsequent legal case generated widespread protests and coverage around the world. Born in the city of Delhi one year after Singh, Raina allowed a wrenching identification with the victim to permeate her art. Conjuring the insurgent legacy of Rani Lakshmibai (1828–1858)—who died in combat while helping to lead the Indian rebellion against British domination—the Indian-born, Brooklyn-based painter pressured abstraction to find a way of speaking to gendered violence. The resultant works, which salvage shards of beauty from the wreckage of atrocity, activate a dialectic between transgression and transcendence.

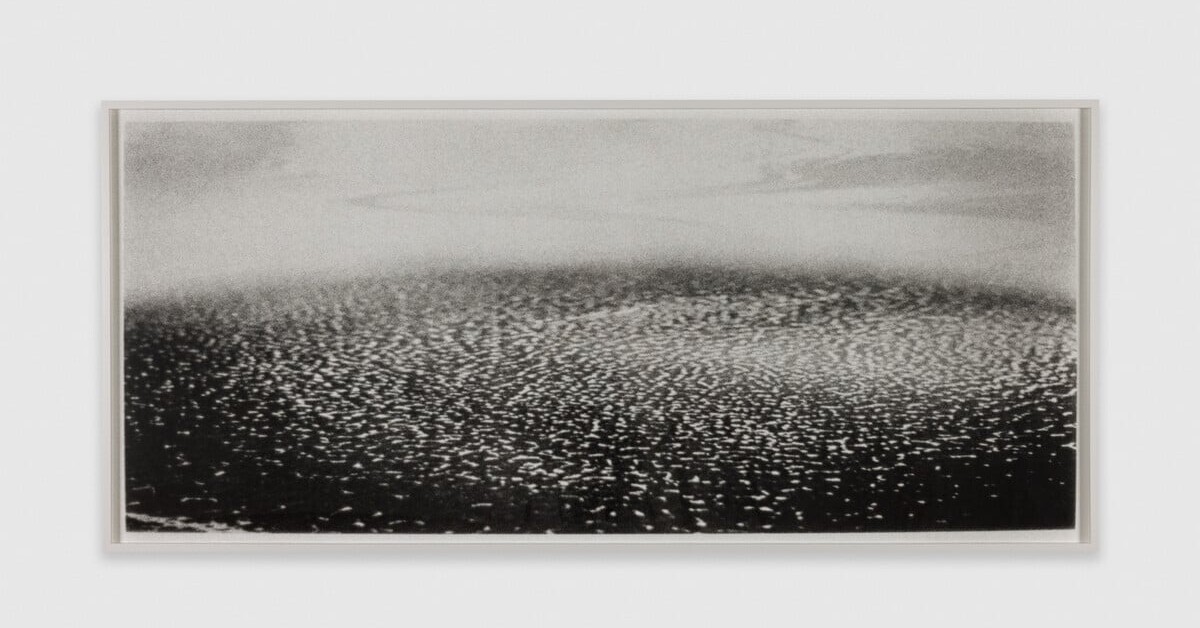

Raina begins with burlap, the rough kind used for sacks of rice. Most often it is raw; sometimes she procures it already pigmented in bright shades of blue and yellow. Occasionally the pieces are sewn together to create a larger, unpredictably grafted skin. Loosely woven together from rough strands of jute, this support is medium-resistant and porous, leaking light from a thousand tiny wounds. Raina mines this permeability by working both sides of a painting, so that forms created on the verso scar the front in ghostly traces. She also abuses her humble ground by applying graphite with great force in repetitive loops and swirls to create cloud- and vessel-like shapes that shadow the painted fields. By bruising a surface that otherwise resists saturation, Raina manages to achieve staggeringly intense colors and effects. Documenting the exhausted energy of their creator, her images wear their battle scars on edges stained with graphite and oil-pastel dust.

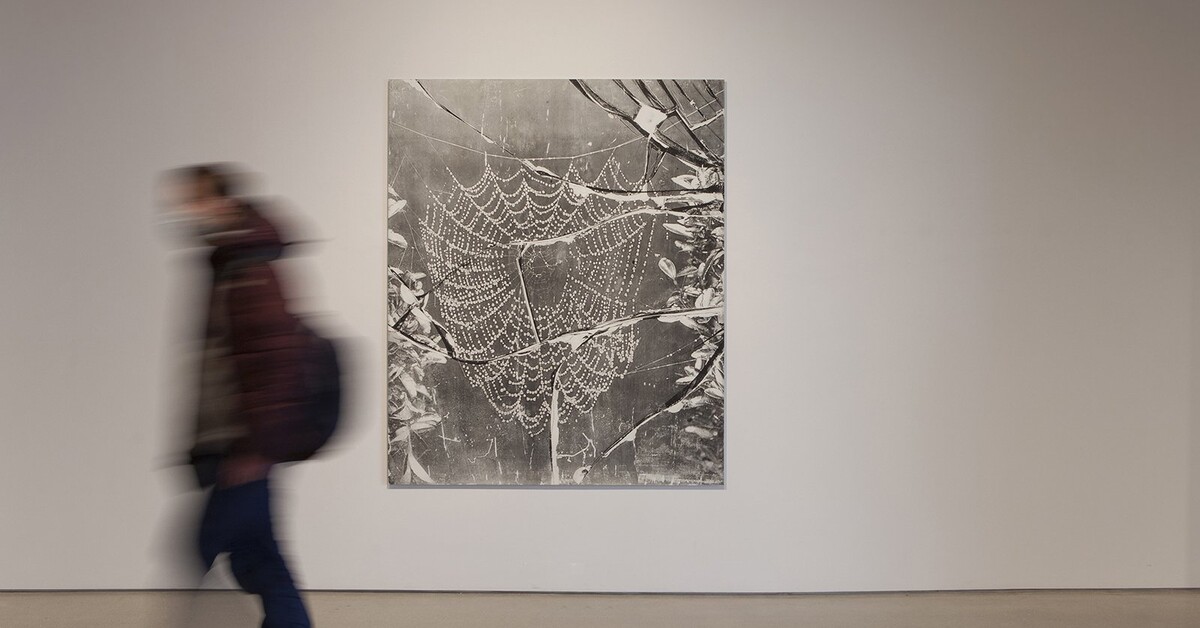

Scarring—both psychic and physical—is an apt metaphor for the materiality that ensues from Raina’s method. Like cicatrices, or tissues that form over a wound, the blemished surfaces of her paintings conjure the counterfactual through their disfigurement of front and back. What could have been different, and what might be different still? In Wish It Was Otherwise; Lack Of—Revisited, 2022, Raina returns to the aftermath of the New Delhi crime scene via a fleshy pink figure that hovers vertically on the work’s surface. Tubular forms that recall the rod used to penetrate and disembowel Singh intersect with vaguely intestinal organic yellow, brown, and magenta shapes that would appear as innocent abstractions in any other context. From a purely formal point of view, the painting embodies a transcendent convergence of figuration and abstraction. Considering their genealogy, however, the work’s hatched and fragmented elements invoke devastated embodiment, even as their jewellike tones enrapture. Bisected by a sky-colored crack in the canvas’s dun-hued ground, the headless body floats up, mesmerizing viewers in its ascent beyond the contours of the frame.

In an era in which artworks often sacrifice passion for polish, abstraction rarely feels so urgent. Inspired by historical anticolonial resistance and the ongoing struggle against patriarchal oppression, Raina’s most recent canvases are both haunted by femicide and infused with the spirit of feminist resistance. While painting, the artist became fixated on the horrifying death of twenty-three-year-old Jyoti Singh (1989–2012), who was riding a bus in New Delhi when attacked by a group of men, who raped and murdered her. The incident and subsequent legal case generated widespread protests and coverage around the world. Born in the city of Delhi one year after Singh, Raina allowed a wrenching identification with the victim to permeate her art. Conjuring the insurgent legacy of Rani Lakshmibai (1828–1858)—who died in combat while helping to lead the Indian rebellion against British domination—the Indian-born, Brooklyn-based painter pressured abstraction to find a way of speaking to gendered violence. The resultant works, which salvage shards of beauty from the wreckage of atrocity, activate a dialectic between transgression and transcendence.

Raina begins with burlap, the rough kind used for sacks of rice. Most often it is raw; sometimes she procures it already pigmented in bright shades of blue and yellow. Occasionally the pieces are sewn together to create a larger, unpredictably grafted skin. Loosely woven together from rough strands of jute, this support is medium-resistant and porous, leaking light from a thousand tiny wounds. Raina mines this permeability by working both sides of a painting, so that forms created on the verso scar the front in ghostly traces. She also abuses her humble ground by applying graphite with great force in repetitive loops and swirls to create cloud- and vessel-like shapes that shadow the painted fields. By bruising a surface that otherwise resists saturation, Raina manages to achieve staggeringly intense colors and effects. Documenting the exhausted energy of their creator, her images wear their battle scars on edges stained with graphite and oil-pastel dust.

Scarring—both psychic and physical—is an apt metaphor for the materiality that ensues from Raina’s method. Like cicatrices, or tissues that form over a wound, the blemished surfaces of her paintings conjure the counterfactual through their disfigurement of front and back. What could have been different, and what might be different still? In Wish It Was Otherwise; Lack Of—Revisited, 2022, Raina returns to the aftermath of the New Delhi crime scene via a fleshy pink figure that hovers vertically on the work’s surface. Tubular forms that recall the rod used to penetrate and disembowel Singh intersect with vaguely intestinal organic yellow, brown, and magenta shapes that would appear as innocent abstractions in any other context. From a purely formal point of view, the painting embodies a transcendent convergence of figuration and abstraction. Considering their genealogy, however, the work’s hatched and fragmented elements invoke devastated embodiment, even as their jewellike tones enrapture. Bisected by a sky-colored crack in the canvas’s dun-hued ground, the headless body floats up, mesmerizing viewers in its ascent beyond the contours of the frame.