Love, Fiction and Deep Space: A Review of Brittany Nelson at Patron

Newcity Art / Feb 27, 2024 / by Susan Aurinko / Go to Original

Brittany Nelson, “Starbear and Mars Clouds 1,” 2021, gelatin silver print, 13″ × 10.5″ × 1″/Photo: Brittany Nelson and Patron Gallery

Between 1971 and 1976, extensive letters were penned to science-fiction writer Ursula Le Guin by someone calling themself James Tiptree Jr. who was, in reality, science fiction author Alice B. Sheldon. This exchange, which lasted five years, was the inspiration for the research that yielded this exhibition, Brittany Nelson’s third solo show at Patron Gallery. Nelson’s fascination with the correspondence and its relation to both space and gender creates an intriguing foray into life and the outer space.

Entering the gallery, one is met by a custom-made desk with a typewriter built into it, perpetually typing the word “Starbear,” Tiptree/Sheldon’s flirtatious pet name for Le Guin. The name in blue ink is scattered across the page wherever it would have appeared in Tiptree’s copious letters. Nelson uses the typewriter, a non-human writer, as a metaphor for Tiptree’s pseudonym. This piece sets the tone for a remarkable exhibition.

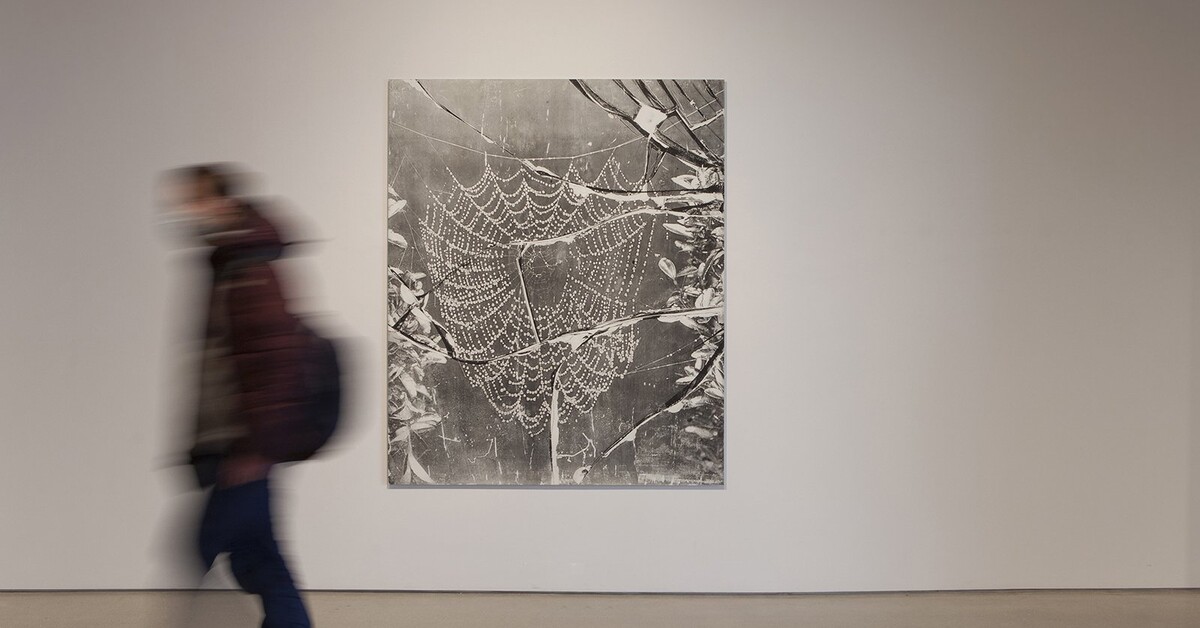

Brittany Nelson, “Solaris Ocean #2,” 2023, unique silver gelatin print, 32.375″ × 72.375″/Photo: Brittany Nelson and Patron Gallery

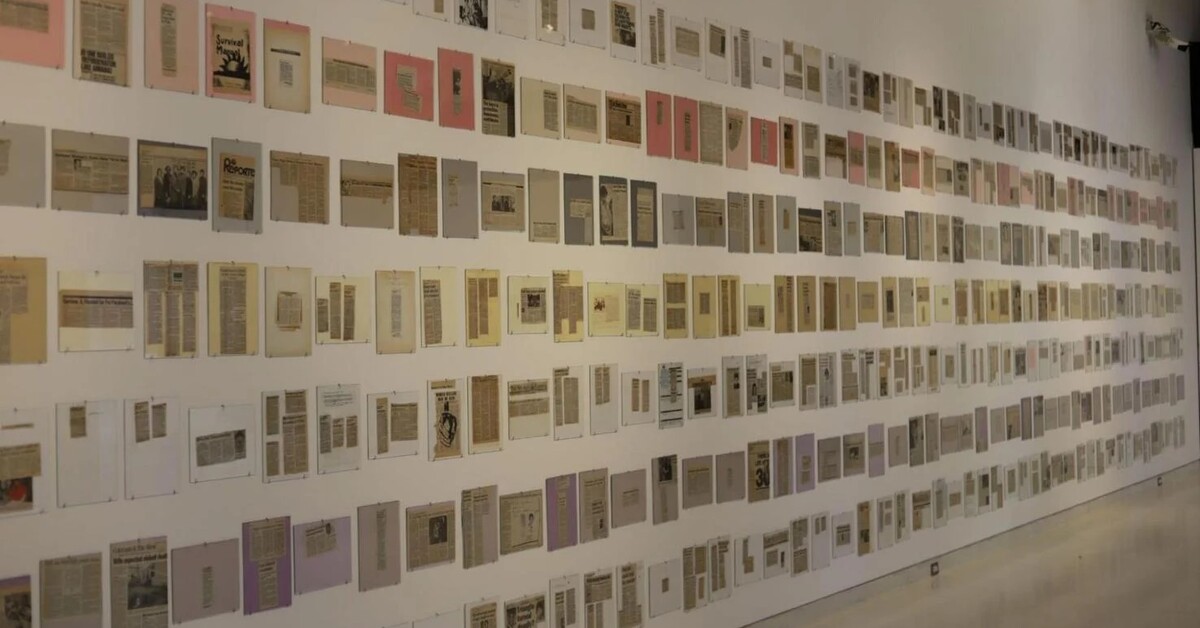

In the large gallery, stills from Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1972 film “Solaris,” in which a psychologist is sent to a space station to investigate the mental problems of the station’s cosmonauts and discovers that the water on the planet draws repressed memories and obsessions from those who drink it. Using one of the last extant Fotar Enlargers from the 1950s, Nelson has created impeccably printed, large-scale gelatin silver prints of these film stills, in all their grainy and blurred glory, to represent the existential nature, not only of the film, but of life itself. We are there, as the evil ocean swirls around us and past and present become future. It is of note that Nelson’s processes are as adept at time travel as science fiction itself. Also in the large gallery are a series of lovely small diptychs in which the lefthand image is a page of Tiptree’s letters to Le Guin, paired with a film still from the Tarkovsky film. The letters are subtle—only the word “Starbear” appears, in its locations on the actual letters.

Brittany Nelson, video still of “I can’t make you love me,” 2023-2024, single-channel video/Photo: Brittany Nelson and Patron Gallery

The absolute blackness of the project space is perfection for Nelson’s video installation, “I can’t make you love me,” wherein she hauntingly pairs music by Bonnie Raitt and others with footage from her research trip to Hat Creek Radio Observatory in Northern California. Nelson joins spotlights sweeping the landscape with captured images of the technology designed to search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence. The satellite dishes turn slowly, longingly searching for validation of life in space. The eight-minute video is mesmerizing, both poetic and eerie, and draws the viewer like a magnetic force. I watched it through twice and would have gladly stayed longer. The music, the sense of time and place, real or imagined, is seductive, much as the letters from Tiptree/Sheldon must have seemed to Le Guin. The fantasy of those letters is repeated in Nelson’s video, making a case for the human desire for meaning and connection. Each of us is an island, forever reaching for another, or in the case of Nelson’s work, the other.