Susie Barstow’s life was a grand adventure but her art was erased

The Washington Post / Jul 24, 2023 / by Philip Kennicott / Go to Original

A historic house museum mounts an exhibition that challenges the conventional narrative of American landscape art

CATSKILL, N.Y. — Susie Barstow is said to have walked 10 to 12 miles a day and sometimes more than twice that. She climbed all the major peaks of the Adirondack, White and Catskill Mountains, traveled the country from end to end, spent time in Europe staying current with developing art trends, and ventured as far as India, China and Japan. She was a successful artist, with an established studio in Brooklyn and elite clients and students. At a time when art was a men’s club, Barstow built not only a commercially successful career, but a formidable reputation as a landscape artist.

So how can it be that Barstow is receiving her first retrospective exhibition since her death a century ago? “Women Reframe American Landscape,” now on view at the Thomas Cole National Historic Site, offers not only a beguiling introduction to her accomplished work, but a case study in the dynamics of historical erasure. Unlike how Hollywood might tell the story of her career, as a struggling artist’s heroic attempt to be recognized, included and patronized, this exhibition presents a more complex truth. Barstow was successful until she was forgotten.

And the forgetting was not just the passive neglect in which the renown of the artist, if they lack posthumous champions, decays into oblivion as new forms and styles supplant older ones. It was more active, and intentional, the work of scholars and critics decades after Barstow died. That process was driven by a critical agenda, the need to invent a plausible and appealing history of American art, with a clear sense of progress and purpose, while burnishing away things that do not quite fit the neat, linear arc of that storyline.

Barstow was born in 1836, to a prosperous upper-middle class merchant family. She was well educated, including time at Rutgers Female Institute and the Cooper Union, and by the 1870s, she had built a successful career as an independent painter. The exhibition includes work made from the 1860s until the early years of the 20th century, including landscapes that would have been familiar to Thomas Cole, the most influential of the first generation of Hudson River School painters, a loosely defined group of landscape artists mostly based in and around New York in the middle of the 19th century. She also painted more topographically dramatic scenes of the American West and European landscapes with a gauzy and poetic bent.

She was working at a time when the idea of a Hudson River School was being defined and debated. Cole had made his home in the Catskills, and flourished as a painter devoted to the scenery of the Northeast, as well as dramatic allegorical series and architectural fantasies. Barstow arrived on the scene as the Hudson River School was starting to feel passé, at least to many critics and younger artists who increasingly had the opportunity to study in Europe.

In the middle of the 20th century, when scholars began paying more serious attention to 19th century American art and the Hudson River School painters, Barstow, along with other female artists included in this exhibition, was left out of the story. The curators of “Women Reframe the American Landscape,” Nancy Siegel, Kate Menconeri and Amanda Malmstrom, have dramatized this moment by pairing the retrospective of Barstow with a second exhibition of contemporary women artists installed in Cole’s historic home and original studio.

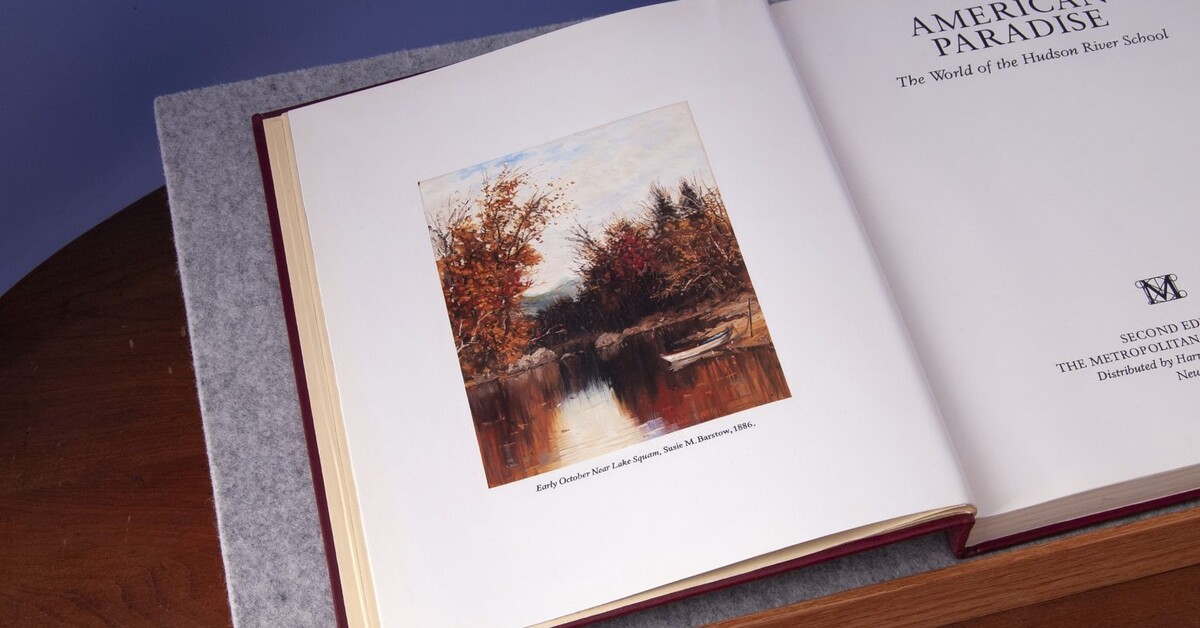

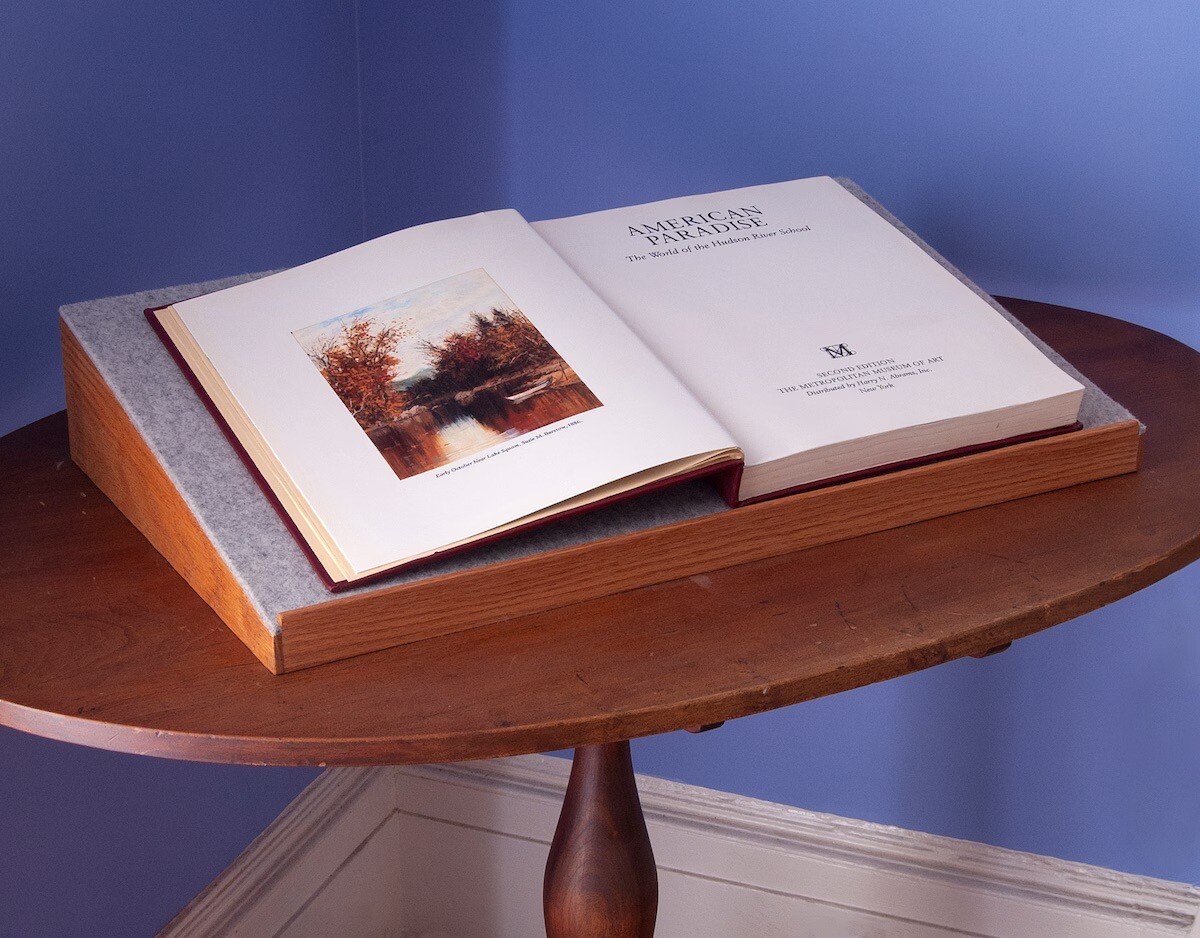

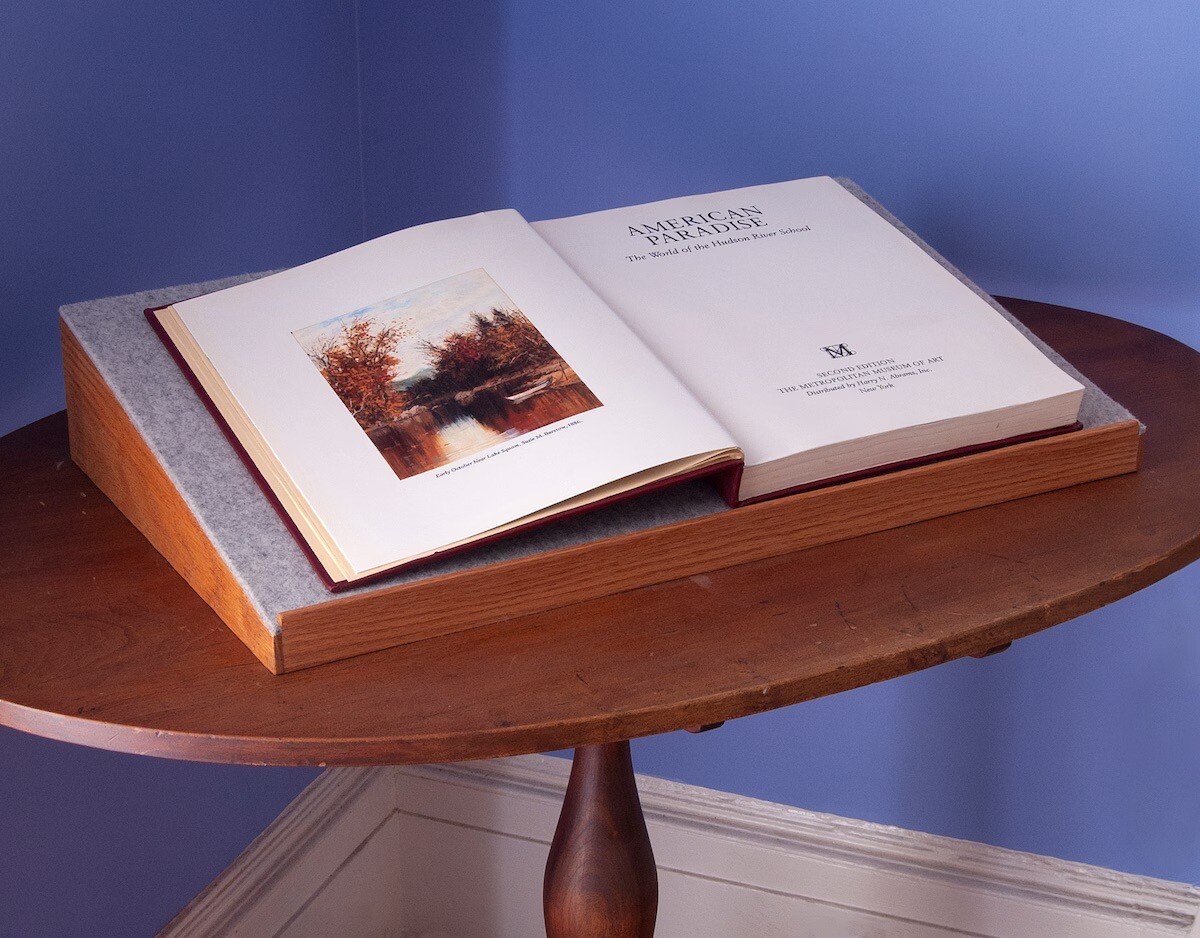

It is a strong, thoughtful, disconcerting show by some of this country’s best artists, including Jaune Quick-To-See Smith, Teresita Fernández, Kay Walkingstick and the Guerrilla Girls, that argues with old and settled ideas about American landscape. Among those works is a trompe l’oeil sculpture by Anna Plesset, depicting a subtly altered art catalogue for a landmark exhibition of Hudson River School artists at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “American Paradise (Second Edition)” depicts the title pages of that book with one of Barstow’s landscapes included as the frontispiece. In fact, the 1987 exhibition included no work by any woman artist.

A small sign asks visitors not to touch the sculpture, which is displayed on a table as if some absent scholar was just about to return to its perusal. I reached for the book instinctively, even before I could process the message to keep my hands off. The first response I registered intellectually was: It is not real. There is both delight in the idea that an artist’s skill has successfully fooled you, as well as the kernel of skepticism that keeps us from being subsumed or engulfed or enslaved by illusions.

Delight and skepticism have not always been well balanced in the history of American landscape. Cole is an artist who delights us, and his home is a pilgrimage site for people who love the landscape of the Hudson River and the idealized way in which Cole and his successors presented it. But as the women and Native American artists in this exhibition point out, his idea of landscape celebrated a pristine wilderness, empty and unsullied by human hands. In fact, he lived during an age of terrible and cruel displacement of Native peoples off lands they had inhabited, tended and altered for centuries.

Also, during his lifetime, the landscape he loved was being rapidly despoiled by logging and industry. So, his paintings, like many others made during the 19th century, deny both the past and future of the land depicted, how it was always inhabited and is so easily destroyed. They reduce the act of looking at the landscape to pure pleasure, without any sense of obligation, responsibility or ethical engagement.

We might ask if Barstow, as a female artist, made paintings that function any differently. It is hard to describe her work without adjectives freighted with gender connotations. In general, she favored intimate views of nature, often in vertical format which creates a sense of the viewer being in and among the trees rather than surveying the breadth of a scene. Many of them are lightly domesticated, with a glimpse of a house or a small boat left idle by absent actors. Texture and detail predominant over grandeur and scale.

In one of the most striking paintings, the 1885 “Pool in the Woods,” once owned by preacher and abolitionist Henry Ward Beecher, water seems to have pooled on a roadway or some cleared surface, reflecting the autumn light and yellow leaves, beneath a long architectural nave formed by inclined trees. Transcendentalism seems balanced with a fading sense of Christian spirituality, all held together by a thin sheet of water over a man-made incursion into nature.

One senses Cole would have condescended to this work. In a short tract known as the Lecture on Art written around 1845, he made scale essential to the impact of landscape painting. Small paintings were to birdsong as grand landscape paintings were to mighty church organs: “Space is as necessary for effect in painting as volume of sound in music.”

That idea likely lingered in the subconscious of male scholars when the Hudson River School was being analyzed and celebrated in the middle of the last century. Smaller works, intimate in focus, rich in observation and speaking more of bodies at one with nature rather than minds enraptured by its grandeur, likely fell by the wayside. And along with it, the entirety of careers and legacies like the one Barstow built.

The Cole house does impressive work for a small historic museum. The new exhibition is a model for how one can both respect and be critical of historic figures, the times they lived in and the work they left behind. The Cole house curators and stewards get the mix of delight and skepticism just right. Barstow’s paintings, along with the contemporary works included in this show, add complexity and nuance to the history of American landscape.

CATSKILL, N.Y. — Susie Barstow is said to have walked 10 to 12 miles a day and sometimes more than twice that. She climbed all the major peaks of the Adirondack, White and Catskill Mountains, traveled the country from end to end, spent time in Europe staying current with developing art trends, and ventured as far as India, China and Japan. She was a successful artist, with an established studio in Brooklyn and elite clients and students. At a time when art was a men’s club, Barstow built not only a commercially successful career, but a formidable reputation as a landscape artist.

So how can it be that Barstow is receiving her first retrospective exhibition since her death a century ago? “Women Reframe American Landscape,” now on view at the Thomas Cole National Historic Site, offers not only a beguiling introduction to her accomplished work, but a case study in the dynamics of historical erasure. Unlike how Hollywood might tell the story of her career, as a struggling artist’s heroic attempt to be recognized, included and patronized, this exhibition presents a more complex truth. Barstow was successful until she was forgotten.

And the forgetting was not just the passive neglect in which the renown of the artist, if they lack posthumous champions, decays into oblivion as new forms and styles supplant older ones. It was more active, and intentional, the work of scholars and critics decades after Barstow died. That process was driven by a critical agenda, the need to invent a plausible and appealing history of American art, with a clear sense of progress and purpose, while burnishing away things that do not quite fit the neat, linear arc of that storyline.

Barstow was born in 1836, to a prosperous upper-middle class merchant family. She was well educated, including time at Rutgers Female Institute and the Cooper Union, and by the 1870s, she had built a successful career as an independent painter. The exhibition includes work made from the 1860s until the early years of the 20th century, including landscapes that would have been familiar to Thomas Cole, the most influential of the first generation of Hudson River School painters, a loosely defined group of landscape artists mostly based in and around New York in the middle of the 19th century. She also painted more topographically dramatic scenes of the American West and European landscapes with a gauzy and poetic bent.

She was working at a time when the idea of a Hudson River School was being defined and debated. Cole had made his home in the Catskills, and flourished as a painter devoted to the scenery of the Northeast, as well as dramatic allegorical series and architectural fantasies. Barstow arrived on the scene as the Hudson River School was starting to feel passé, at least to many critics and younger artists who increasingly had the opportunity to study in Europe.

In the middle of the 20th century, when scholars began paying more serious attention to 19th century American art and the Hudson River School painters, Barstow, along with other female artists included in this exhibition, was left out of the story. The curators of “Women Reframe the American Landscape,” Nancy Siegel, Kate Menconeri and Amanda Malmstrom, have dramatized this moment by pairing the retrospective of Barstow with a second exhibition of contemporary women artists installed in Cole’s historic home and original studio.

It is a strong, thoughtful, disconcerting show by some of this country’s best artists, including Jaune Quick-To-See Smith, Teresita Fernández, Kay Walkingstick and the Guerrilla Girls, that argues with old and settled ideas about American landscape. Among those works is a trompe l’oeil sculpture by Anna Plesset, depicting a subtly altered art catalogue for a landmark exhibition of Hudson River School artists at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “American Paradise (Second Edition)” depicts the title pages of that book with one of Barstow’s landscapes included as the frontispiece. In fact, the 1987 exhibition included no work by any woman artist.

A small sign asks visitors not to touch the sculpture, which is displayed on a table as if some absent scholar was just about to return to its perusal. I reached for the book instinctively, even before I could process the message to keep my hands off. The first response I registered intellectually was: It is not real. There is both delight in the idea that an artist’s skill has successfully fooled you, as well as the kernel of skepticism that keeps us from being subsumed or engulfed or enslaved by illusions.

Delight and skepticism have not always been well balanced in the history of American landscape. Cole is an artist who delights us, and his home is a pilgrimage site for people who love the landscape of the Hudson River and the idealized way in which Cole and his successors presented it. But as the women and Native American artists in this exhibition point out, his idea of landscape celebrated a pristine wilderness, empty and unsullied by human hands. In fact, he lived during an age of terrible and cruel displacement of Native peoples off lands they had inhabited, tended and altered for centuries.

Also, during his lifetime, the landscape he loved was being rapidly despoiled by logging and industry. So, his paintings, like many others made during the 19th century, deny both the past and future of the land depicted, how it was always inhabited and is so easily destroyed. They reduce the act of looking at the landscape to pure pleasure, without any sense of obligation, responsibility or ethical engagement.

We might ask if Barstow, as a female artist, made paintings that function any differently. It is hard to describe her work without adjectives freighted with gender connotations. In general, she favored intimate views of nature, often in vertical format which creates a sense of the viewer being in and among the trees rather than surveying the breadth of a scene. Many of them are lightly domesticated, with a glimpse of a house or a small boat left idle by absent actors. Texture and detail predominant over grandeur and scale.

In one of the most striking paintings, the 1885 “Pool in the Woods,” once owned by preacher and abolitionist Henry Ward Beecher, water seems to have pooled on a roadway or some cleared surface, reflecting the autumn light and yellow leaves, beneath a long architectural nave formed by inclined trees. Transcendentalism seems balanced with a fading sense of Christian spirituality, all held together by a thin sheet of water over a man-made incursion into nature.

“Pool in the Woods” is an oil on canvas painting by Susie Barstow. (John Groo/Harriet Beecher Stowe Center)

One senses Cole would have condescended to this work. In a short tract known as the Lecture on Art written around 1845, he made scale essential to the impact of landscape painting. Small paintings were to birdsong as grand landscape paintings were to mighty church organs: “Space is as necessary for effect in painting as volume of sound in music.”

That idea likely lingered in the subconscious of male scholars when the Hudson River School was being analyzed and celebrated in the middle of the last century. Smaller works, intimate in focus, rich in observation and speaking more of bodies at one with nature rather than minds enraptured by its grandeur, likely fell by the wayside. And along with it, the entirety of careers and legacies like the one Barstow built.

The Cole house does impressive work for a small historic museum. The new exhibition is a model for how one can both respect and be critical of historic figures, the times they lived in and the work they left behind. The Cole house curators and stewards get the mix of delight and skepticism just right. Barstow’s paintings, along with the contemporary works included in this show, add complexity and nuance to the history of American landscape.