‘The Last Safe Abortion’ – A photo exhibition at the Minneapolis Institute of Art

MPR News / Aug 9, 2023 / by Alex V. Cipolle / Go to Original

Artist Carmen Winant installs “The Last Safe Abortion” in early August.Courtesy of the Minneapolis Institute of Art

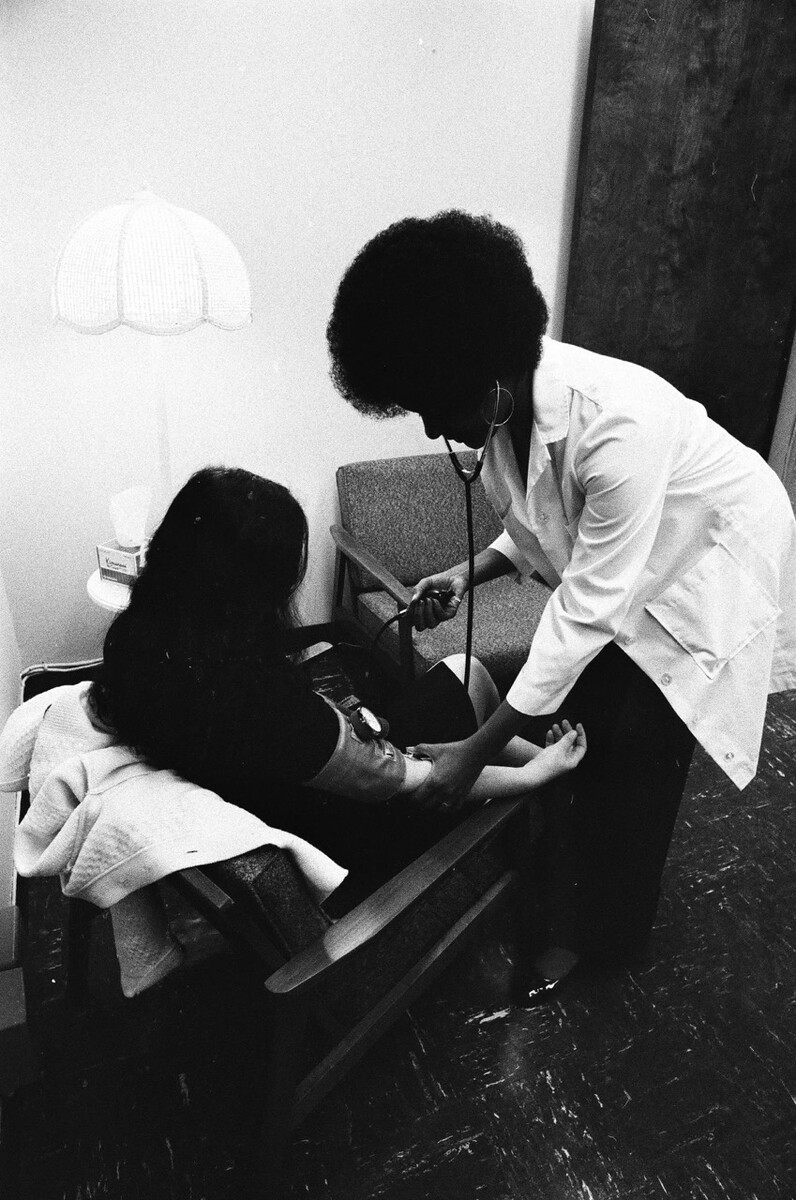

At the Minneapolis Institute of Art, there is a series of archival photographs on display that document a patient in the before-and-after process of a surgical abortion circa the 1980s.

The series is part of the new Mia exhibition “The Last Safe Abortion” by Ohio-based artist Carmen Winant. The exhibition includes hundreds of historic, archival and contemporary photographs taken across the Midwest, defined by Winant as Minnesota, Iowa, Nebraska, Kentucky, Indiana, Illinois, North Dakota and Ohio.

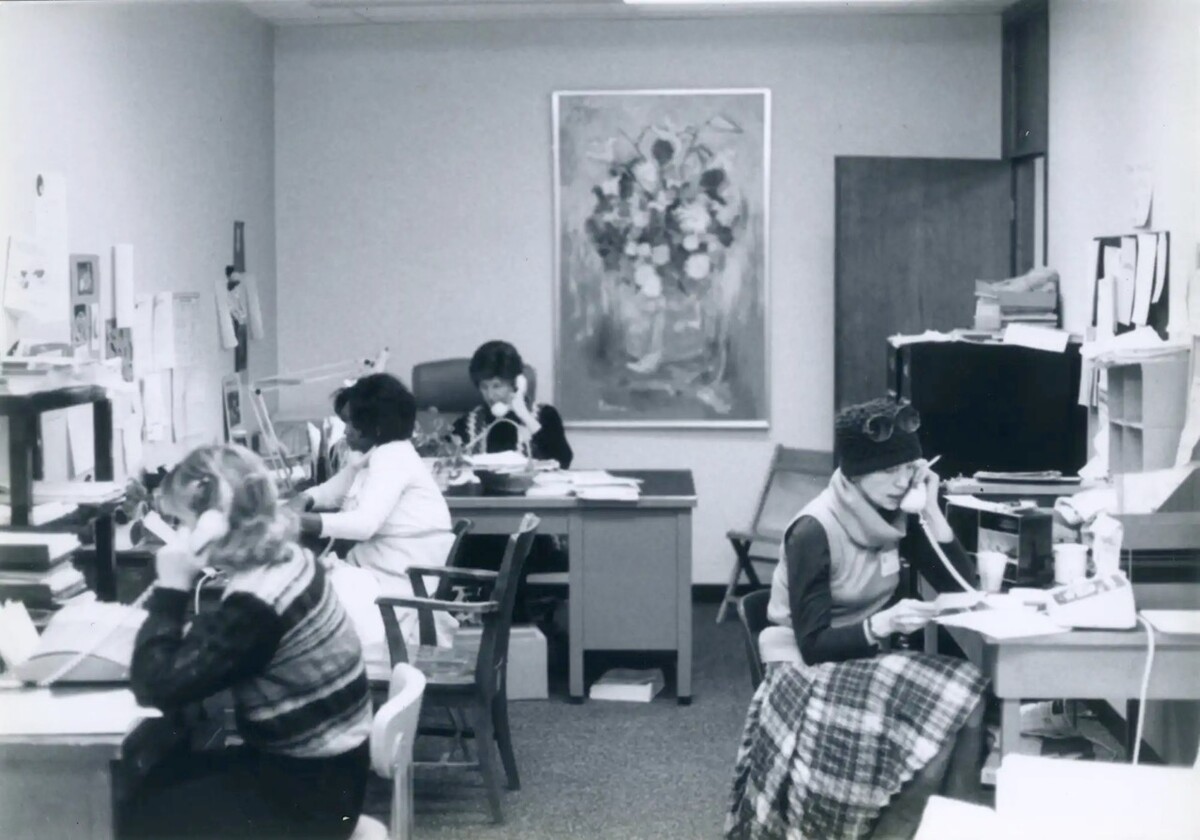

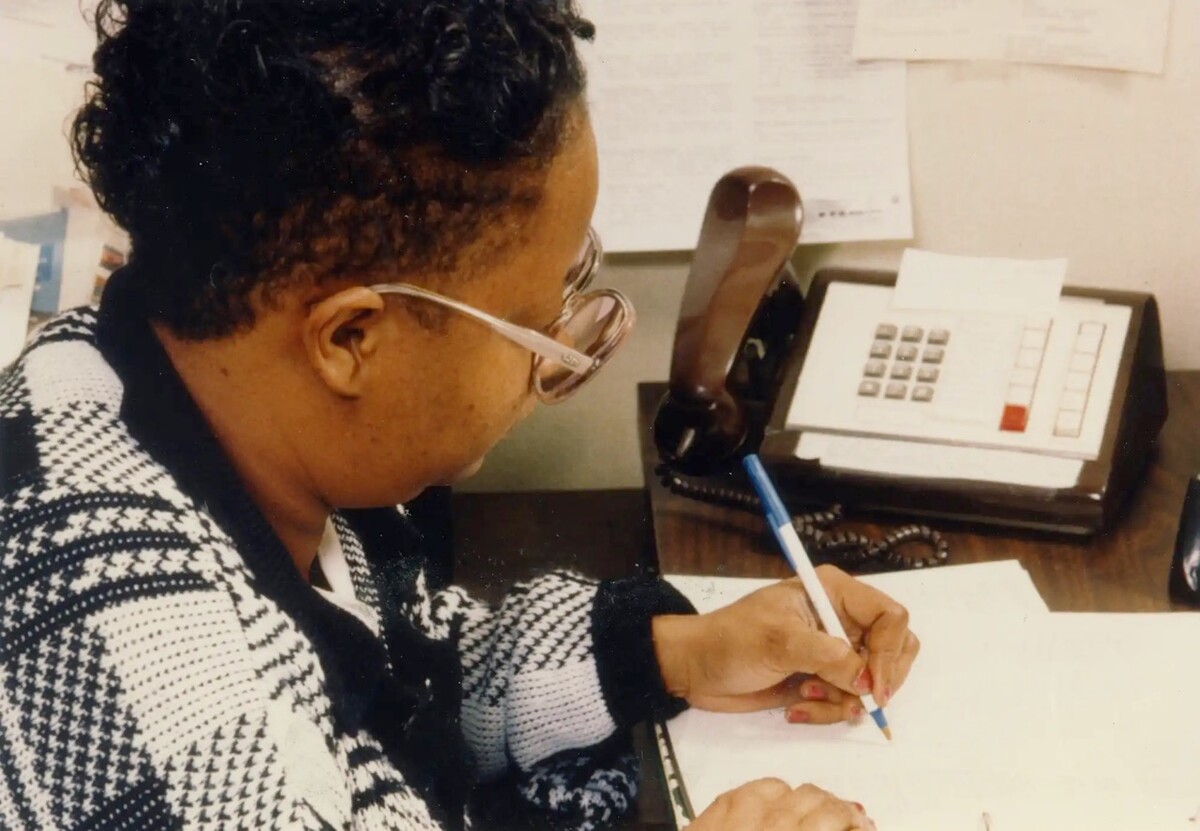

The photos span from around the Roe v. Wade ruling in 1973 to the Dobbs v. Jackson decision in 2022 and its aftermath. They highlight the daily lives of reproductive health care workers — scheduling appointments, conducting training sessions, tending to patients.

The surgical abortion series is staged, a sort of educational exercise for a clinic in Ohio. The story begins with images of a woman making a phone call to schedule an appointment and a staff person picking up on the other end at the clinic. It unfolds with more photos — sitting in a waiting room, getting blood drawn, ending with the woman recovering with a heating pad, reading a magazine.

“It’s so beautiful,” says Winant. “The power of photography as a heuristic device of teaching and learning, that there are things that we do in our lives frequently, that we don’t see.”

“I thought that was very moving and effective, and was really such a reminder of the overall thrust of the project,” Winant adds of the series, “by virtue of using images, photographic images, as a tool in service of community, education and coalition.”

“I’m reminded of how we need each other in the struggle — how important it is to normalize this work — and I’m reminded that these are human beings.” — Carmen Winant.Courtesy of Iowa Women’s Archive, University of Iowa

Winant is an art professor at Ohio State University who also describes herself as a feminist, part-time activist and mother of two. She has been working on “The Last Safe Abortion” since 2019, with the collaboration of the Mia’s Casey Riley, the chair of global contemporary art and curator of photography and new media.

Riley says the exhibition illustrates that history isn’t solely composed of monumental moments.

“History is also showing up to work and answering the phone and talking to your colleagues and celebrating a birthday, or whatever, just all of that mundane stuff,” Riley says.

“When you look at this all put together you realize what a movement is: A movement is a collective enterprise. A movement is something that inspires a number of different people to act on an everyday basis towards these goals that may feel kind of abstract, but actually are incredibly consequential and meaningful and grounded in our life.”

Riley says this is a unique exhibition for the Mia. “There hasn’t been a project like this,” Riley says. “But I’d also say that there’s a lot of art that’s thinking about reproductive health.”

Winant has long been what Riley describes as a “lens-based” artist. She works with the camera and plumbs photographic archives to investigate women’s and LGBTQ+ issues.

Winant says she purposely chose banal, quotidian, “unsensational” imagery for the exhibition, rather than photos of protests or confrontation, to normalize the labor behind reproductive rights.

“Because the visuality of abortion has been really harnessed and weaponized by anti-abortion activists … Utilizing photography really effectively as an ideological tool,” Winant explains. “So, it became really important for me to think about how to [counter] that with photography and thinking about the visuality of this care work.”

“History is also showing up to work and answering the phone and talking to your colleagues and celebrating a birthday, or whatever, just all of that mundane stuff.” — Casey Riley.Courtesy of Special Collections, Cleveland State University

In an Aug. 8 article, Vanity Fair states that Winant is “building a new visual language around abortion.”

The Mia provided Winant the resources to complete the project to do archival research at many institutions, including the University of Minnesota’s Social Welfare History Archives, and working with clinics such as the Red River Clinic in Moorhead, Minn., and Whole Woman’s Health of Minnesota in Bloomington, Minn. Winant herself traveled to clinics to take her own photographs as well.

“It was really important to me to think about not just how I relate to abortion access and care and legislation on some grand ideological scale,” Winant says. “But really to think about how and where it operates where I live, how it affects me and my neighbors, and my students and my children.”

Winant says it was a slow, sensitive process making contact and building trust with clinics, especially after the Dobbs decision removed federal protections for abortion. Two of the states Winant included in the project, North Dakota and Indiana, instituted full bans after the fall of Roe. Over the course of the project, Winant says, the clinics essentially became “war zones.”

“It felt really urgent as I worked. Clinics that I was working with were shuttering as we were in conversation,” Winant says. “In that regard, it was unlike any project that I’ve ever worked on in real-time in regard to the real-world stakes.”

“It felt really urgent as I worked. Clinics that I was working with were shuttering as we were in conversation.” — Carmen Winant.Courtesy of Iowa Women’s Archive, University of Iowa.

The name for the exhibition, “The Last Safe Abortion,” came verbatim from discussions with health care workers.

“They all almost verbatim iterated the same version of this sentence, which is: ‘We will provide the last safe abortion in — fill in the blank — Ohio, Indiana, North Dakota, Kentucky, etc.,” Winant recalls. “It was a statement that struck me as being so resolute, full of resilience, and also so elegiac — as a matter of not if, but when.”

Through the years of this project, Winant says she found that most health care workers were increasingly tired — but committed.

“They were staying and doing their work. They were finding solutions through, but they’re people and, you know, they’re angry, and they’re also terrified,” she says. “I’m reminded of how we need each other in the struggle — how important it is to normalize this work — and I’m reminded that these are human beings.”

“The Last Safe Abortion” will be on view in the Mia’s Perlman Gallery through Dec. 31. Winant will give an artist talk Sept. 21 at the Minneapolis museum.