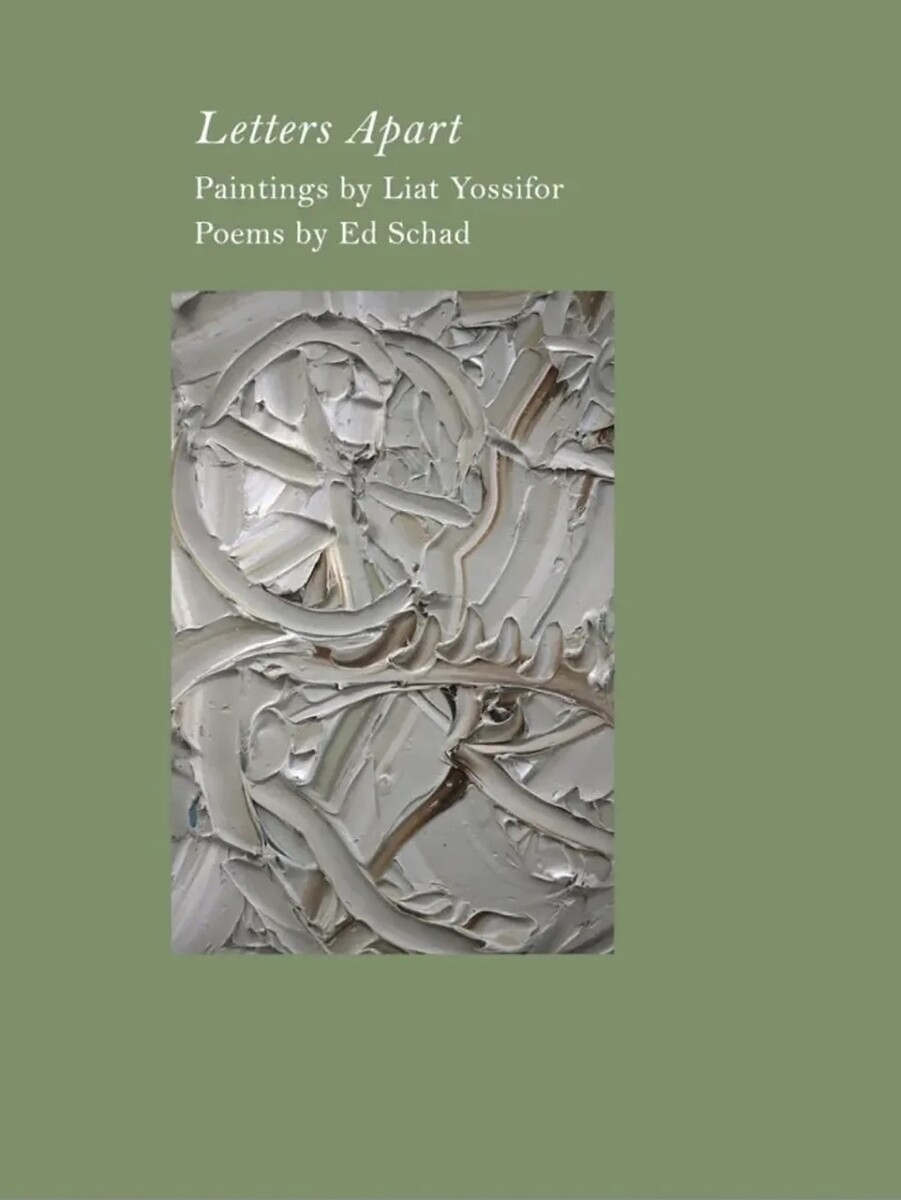

Letters Apart

The Art Section / Sep 1, 2023 / by Ed Schad and Liat Yossifor | / Go to Original

Published by DoppelHouse Press, Los Angeles, California and copublished with La Verne University, La Verne, California 2023

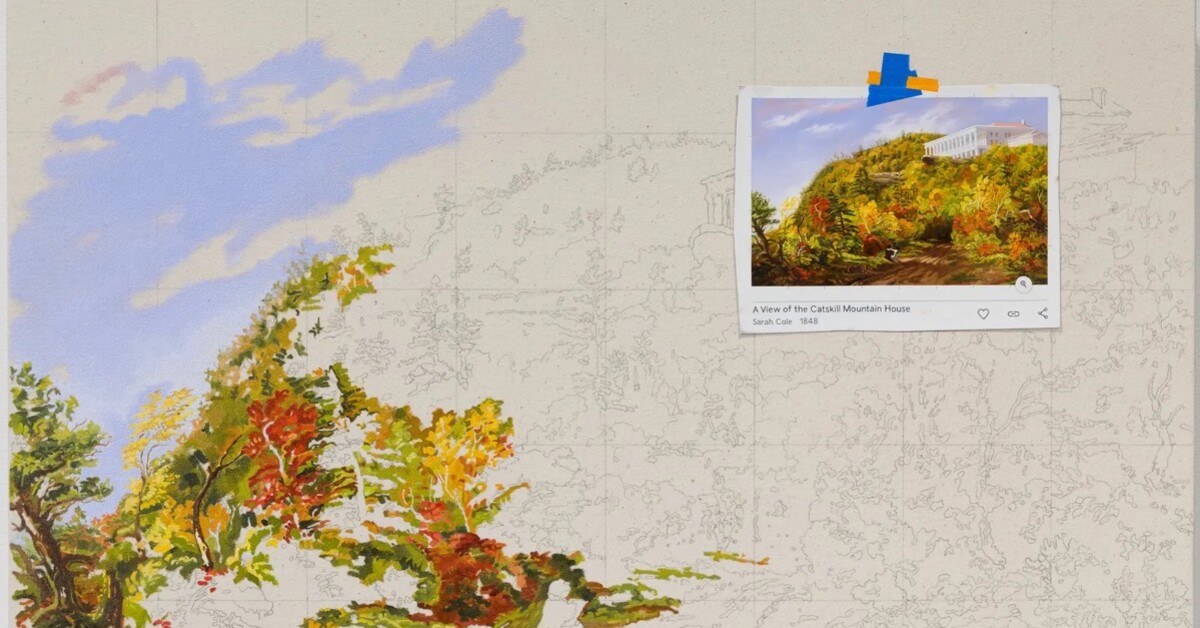

Letters Apart, Paintings by Liat Yossifor and Poems by Ed Schad, 2023 page 58/59; Liat Yossifor, Eye and Circle, 2020, oil on paper, 11 by 8 inches,Collection Turki Al Khater, Doha, Photography by Jeff Mclane, Los Angeles

Most know Ed Schad from his curatorial work at the Broad Museum in Los Angeles. His exhibition William Kentridge: In Praise of Shadows was brilliant, with its unforgettable breathing machine, the “elephant,” and the inclusion of the map of Palestine halfway through the space. In 2020, Ed’s exhibition, Shirin Neshat: I Will Greet the Sun Again, was titled after a poem by Forugh Farrokhzad. In preparing this exhibition, Ed immersed himself in the work of Iranian poets such as Ferdowsi, Attar (Sholeh Wolpe’s translation of Conference of the Birds), Nizami, and Hafez, amongst others. But the reason I was not surprised to learn that Ed is a poet is how he reacts to visual art, for instance an oil sketch by Constable, or a small oil on tin-plate iron by Goya. He understands scale and what needs to be said and what can be left out. From years of talking with him about painting, I think he is most drawn to studies, prints, etchings, and the small paintings that we need to read, not the ones that hover above us.

Our project together, , was not supposed to be a book. Early on in the pandemic, we started a correspondence where Ed wrote in response to my works on paper; it was just something to do. About ten paintings and poems into the pandemic, we realized it was much more. After over sixty paintings and poems, we knew we had something that was simultaneously a tough record of those days and an escape from them. In his poems, Ed gathers and breaks down his childhood memories while contouring each painting with words. It feels as if he is writing to a painting, and yet the collection evokes a parallel world that is private to Ed.

- Liat Yossifor, Los Angeles, CA

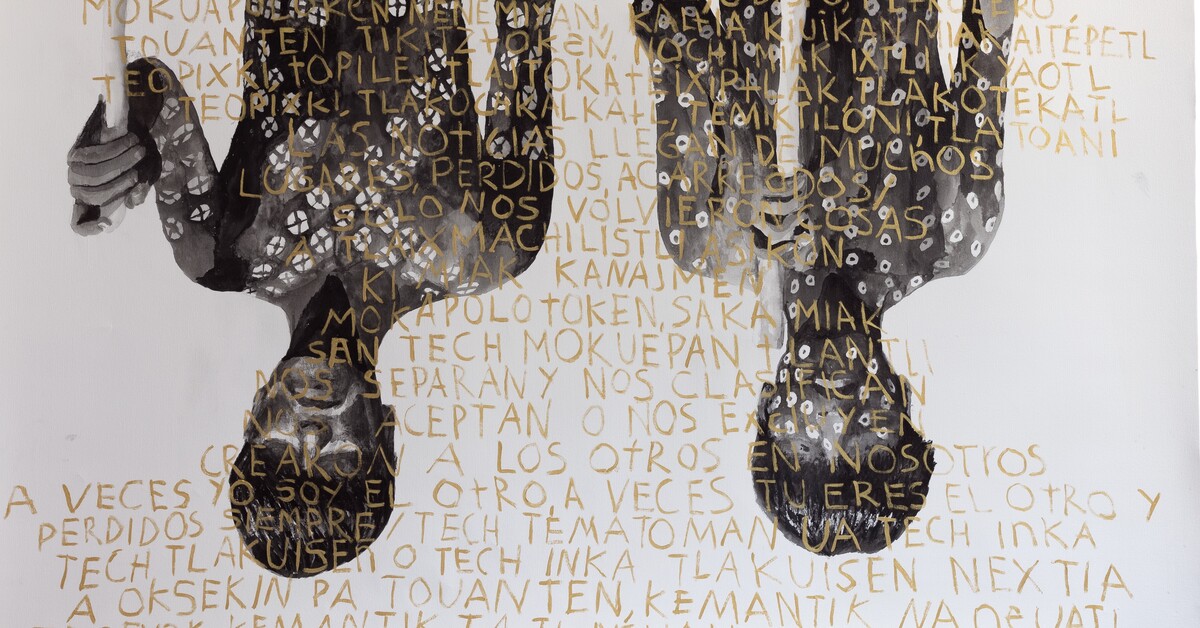

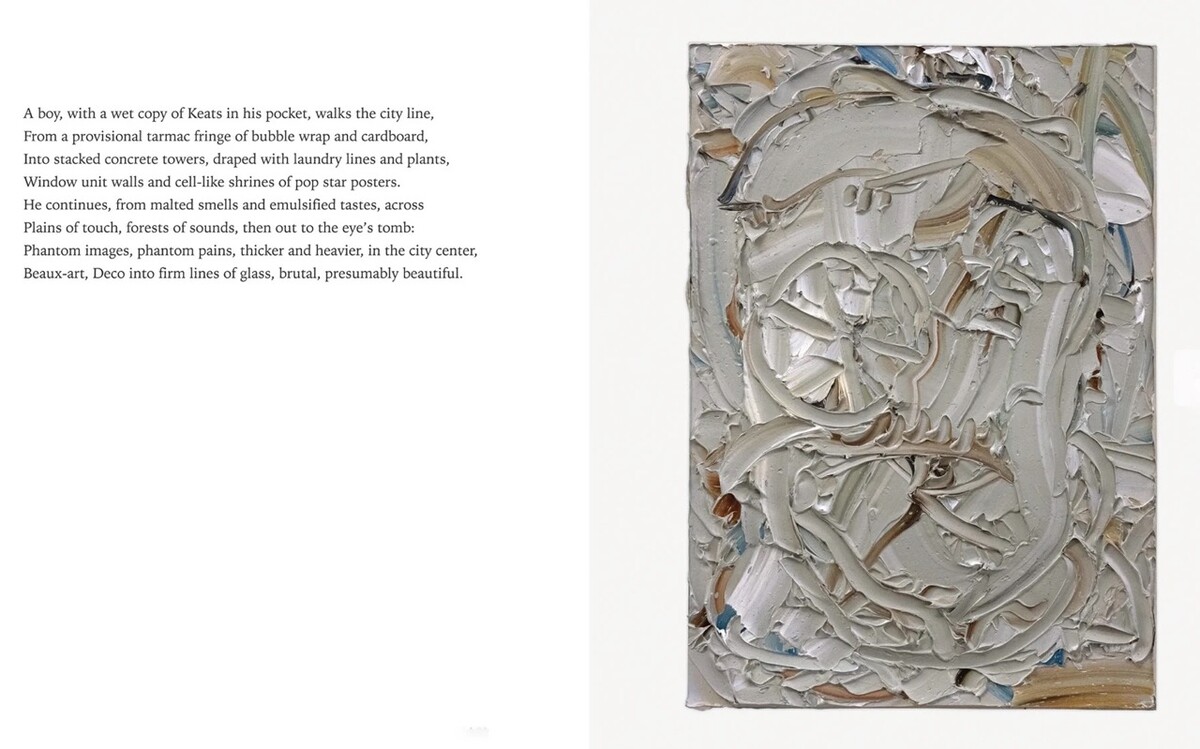

Letters Apart, Paintings by Liat Yossifor and Poems by Ed Schad, 2023 page 72/73; Liat Yossifor, Figure and Earth, 2021, oil on paper, 12 by 9 inches, Private collection, Sydney, Australia, Photography by Jeff Mclane, Los Angeles

Liat Yossifor: Letters Apart is a two-year project and a record of the pandemic. I read one poem at a time during our correspondence, but later, when I read it in full as a collection, I was surprised by how it moves through the stages of the pandemic. Some poems line up totally with the paintings and others jump off the painting/poem page and go elsewhere. Can you speak about one poem of your choosing that had “a mind of its own,” so to speak?

Ed Schad: There are two poems that come specifically to mind: the last poem, which is a list of “Things I Lost,” and a poem about rivers. I think when I wrote those poems I was in a place where no matter what I was doing or involved with, I kept tumbling back home to Texas. Sometimes, there is no door out of your memory. Although your paintings are some of the most amazing corridors around — sometimes I find that your paintings seem like those wonderful expansive hallways in ancient rooming houses that are just as amazing as the rooms themselves — I just could not find a way out of myself. With the river poem, all I needed was one crisscrossing fluid brush stroke to jump into the water of every river I have had a relationship with. With the last poem, I wanted to gather many of the threads and fragments that I had gathered in all these poems and simply declare that I was okay with the fact that I was not sure what they added up to.

LY: As for things adding up, the poems have a location in Texas. This is not a small detail since it gives the poems a home. Your poems were on my mind when I visited Texas. I looked for these coded moments from your poems of how a place works, a place that was otherwise foreign to me. “Things I Lost” starts with a sentence I understand to be about belonging somewhere, and I thought of places I tried to be a part of. The process is slow; we are not in charge of it. I want to ask more about Texas since it comes up in all kinds of shapes and moments from your childhood throughout the book. You are from a complicated place. I read about the stickiness of candy, the snakes on a farm, the sweat, the heat. It’s also a troubled relationship; nothing feels like simple nostalgia, at least not now in recruiting these memories for today’s poems.

ES: When my grandmother died several years ago, I took a walk on her and my grandfather’s farm and on top of the sadness of losing them, I realized that the land, which had been my intimate when I was growing up, was not only alien but even hostile to me. As a kid, I would adventure in that land. I would imagine the corn pickers were the long snouts of dinosaurs and that the grasses were a jungle to be explored. When I encountered an insect or a water moccasin or a snapping turtle, I would study them and hang out with them. I knew every inch of the farm and would follow the natural footpaths of the cows as different routes to the same goal, which was visiting my grandparents. However, it did not feel like a metaphor for loss when I realized that I feared the same grasses as an adult, that I was worried about snakes and was deeply uncomfortable walking through the cockleburs and the thistles. This book is just getting started with understanding how this happened, the gradual division between me and my friends and that land. I would like to write another volume of poems about that day. Evidence of that day can be found all over Letters Apart and maybe that day wants more from me. There is the working mystery of how the land enters the body, but there is also the mechanistic and worldly mystery of how the same land can leave you.

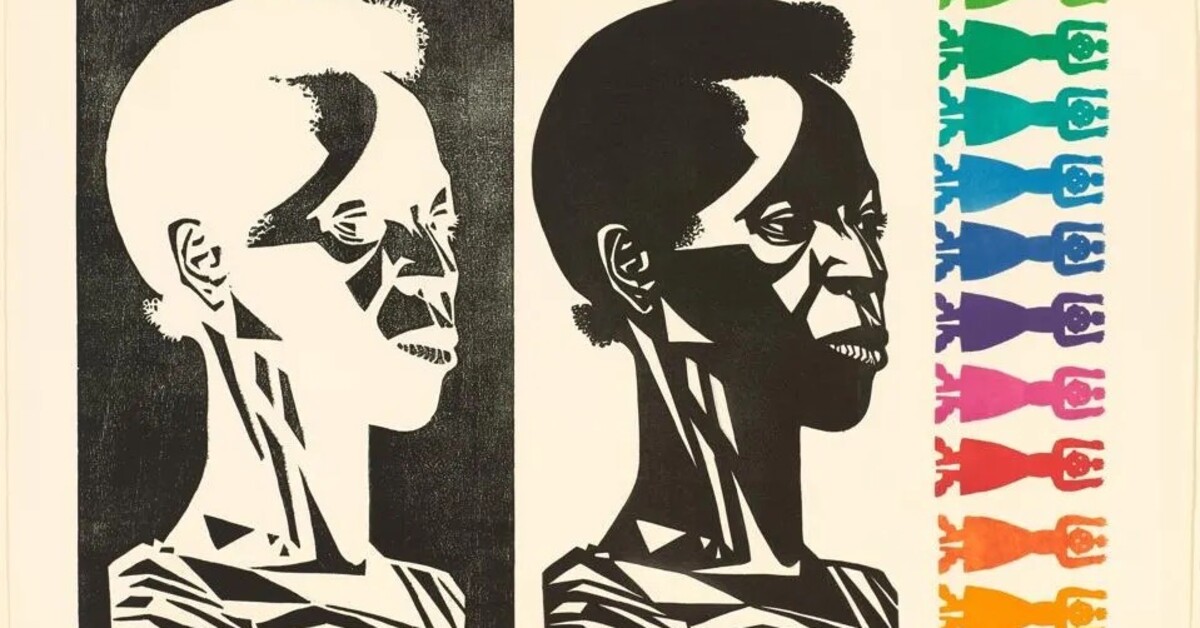

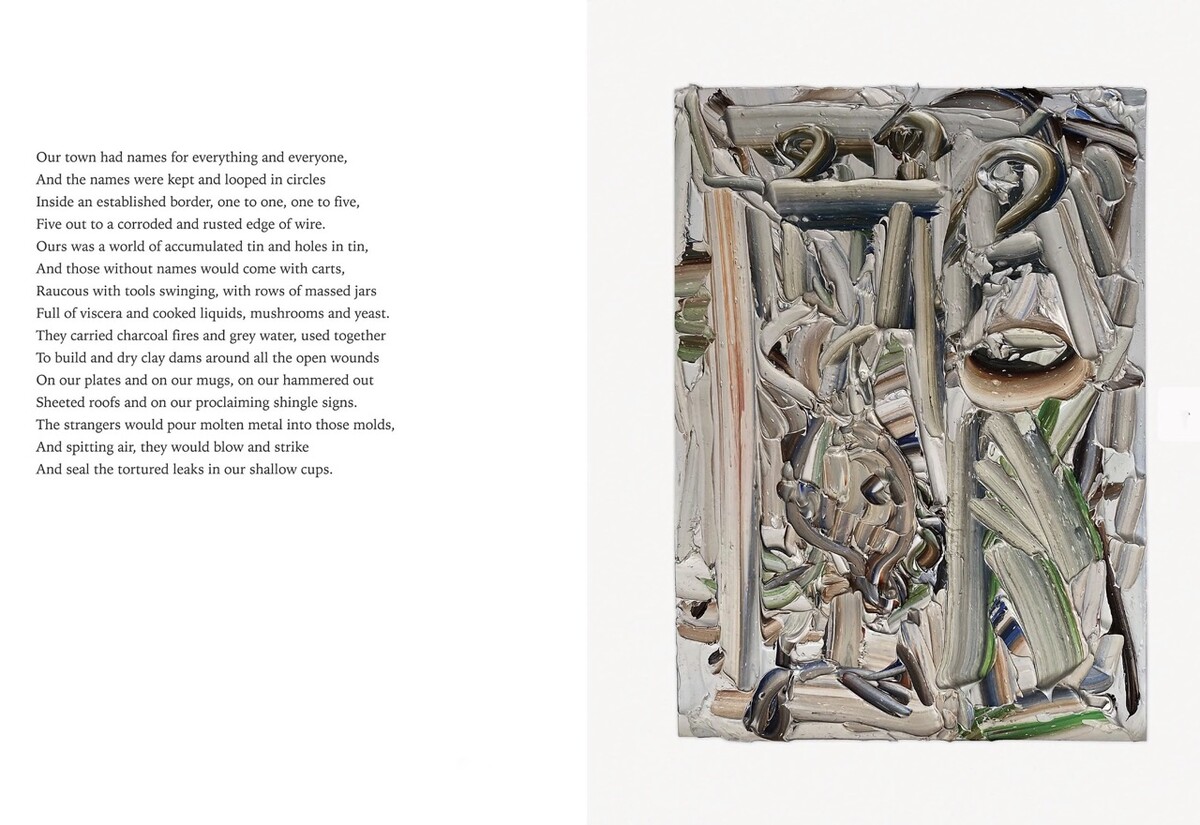

Letters Apart, Paintings by Liat Yossifor and Poems by Ed Schad, 2023 page 20/21; Liat Yossifor, Letters III, 2020, oil on paper, 11 1/4 by 8 1/4 inches,Private collection, Sydney, Australia, Photography by Jeff Mclane, Los Angeles

LY: I hope you will write this Texas volume. That’s why I think it’s fitting that the book ends with “Omens”; it makes me curious to read your next chapter as a poet.

During the poetry reading we held at The University of La Verne, we were asked about the order of things. I sent you a painting and received a poem, and every poem I received influenced the next painting. Poems inspired certain temperatures in paint. This is because I printed the poems and took them to the studio and read while painting. As for your process, I would like to ask if the fact the paintings are letter-sized influenced your writing? Did you compose with the actual objects in mind? Or as screen images? Sometimes, when I view historical works online, it feels even more personal to me. It’s on my screen as if it were made for me. The paintings were transmuted to you like letters, about oil paint but not the real experience of oil on paper. Did that play a part in your writing?

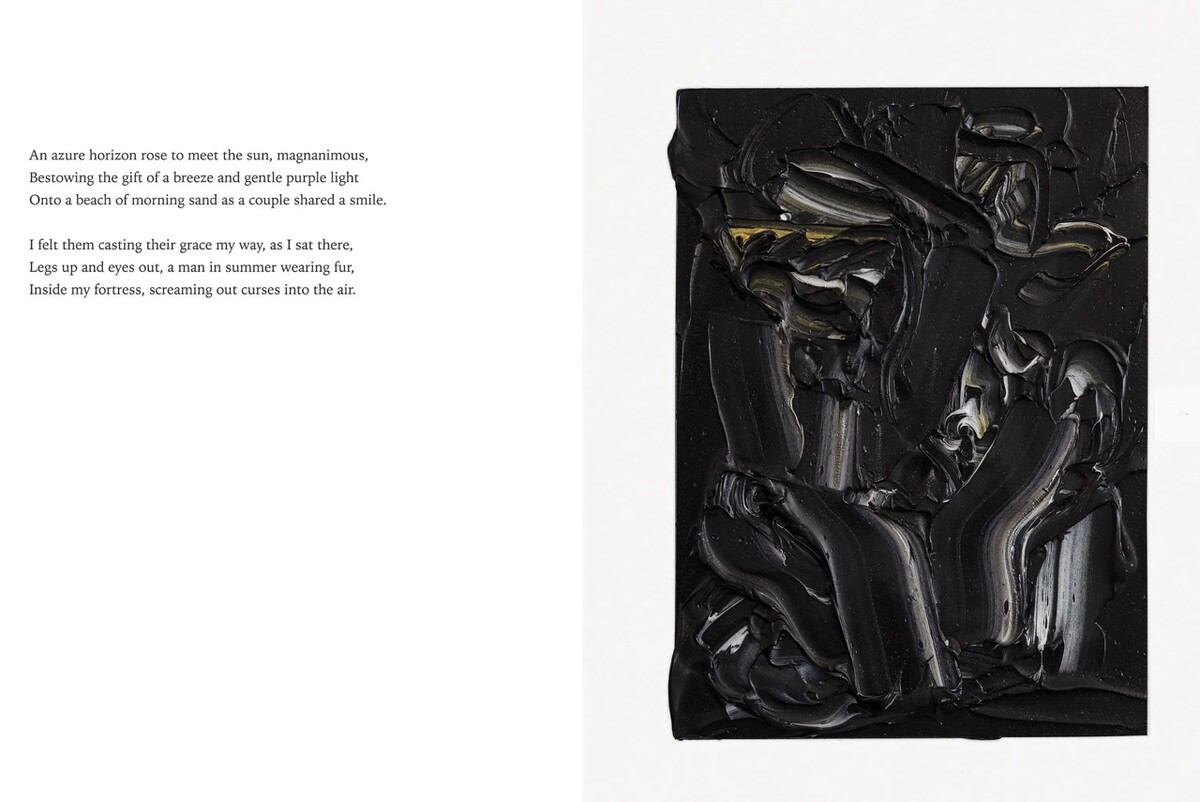

I ask these questions while reading “An azure horizon” again. This is a small large painting and the poem also feels small and large. Please talk about scale, screens, and the distance from the real experience of things that was also the pandemic.

ES: I am not sure if you remember but I think our first conversation — over ten and maybe as many as fifteen years ago — was about scale. We talked about how some artists are naturals at large sizes but cannot make a small work of art to save their lives, and that one of the challenges of being an artist was perpetually tilting against the natural affinities of scale. The small size of your paintings mattered to me. I like to write small poems and my large poems are clunky and full of rhetoric, which my voice cannot handle. I have never published one. One interesting fact that you may not know about how I worked with your paintings is that I spent a lot of time zooming in on the screen, sometimes having just inches of the work filling up the visual field. Sometimes, the depth of one of your cuts or complex passages of buried color were enough to start the sounds and the images of the poem on their way. It is funny you mention that azure horizon poem because I thought about its buried yellows quite a bit, almost like a perfect feeling rising at a particularly bad moment in one’s life, daring one to be happy, daring one to embrace the simple wonders of things. We talk a lot about Max Beckmann’s ocean paintings — how incredible they are in their willful refusal of anything sublime or beautiful. How could I not put Beckmann in a beach chair on a beautiful day? And how could he be wearing anything but a fur coat?

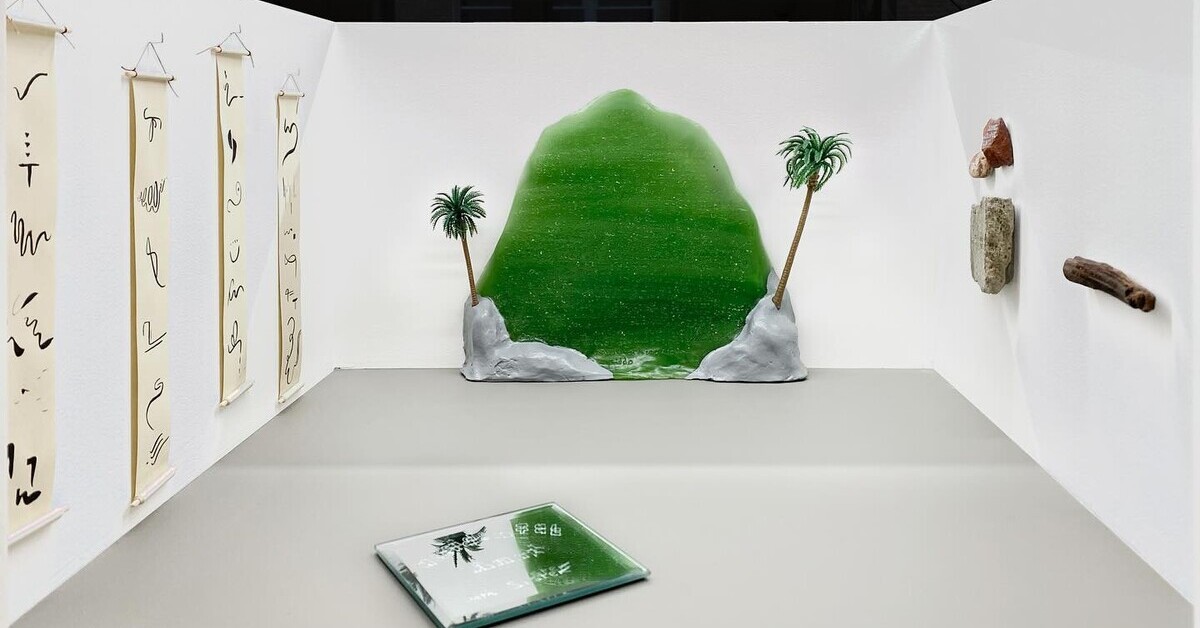

Letters Apart, Paintings by Liat Yossifor and Poems by Ed Schad, 2023 page 16/17; Liat Yossifor, Soft, 2020, oil on paper, 12 1/4 by 8 1/4 inches, Photography by Jeff Mclane, Los Angeles

LY: Small Landscape, Viareggio, 1925, Frankfurt, is a Beckmann painting that is a poem if he ever wrote one. The painting for “An azure horizon” probably happened from staring at this painting for too long.

This brings up your poem “Durer at 32,” a reference to his watercolor The Great Piece of Turf, 1503, that shapes a gothic cathedral out of weeds. This poem feels simple next to some of the others, as if what you saw felt so obvious it just wrote itself. Another art historical reference, to Whistler, is in the poem “Wind and Fog and Rain.” You also shuffle references in “Dutch portraits with decapitating ‘ruffs.’” These art historical moments are all throughout Letters Apart. In your work and who you are, you are constantly surrounded and surrounding yourself with painting. This is a unique position to be in as a poet. Can you talk about this in regard to painting and also specifically for Letters Apart?

ES: I think in my art writing, I have struggled a long time with references. It is a fun parlor game to say that one painting looks like another painting and to try to be as obscure and as deep in that process of x looking like y as one can. However, after only a short time, that game is unsatisfying. One of things I loved about writing poems about your work is that I could discover references and then the act of poetry insisted that I leave them behind and find the life behind them. The painting on which “Durer at 32” is based looks like grass at times but it also looks like a skull, and I tried to locate an event in Durer’s life that encapsulated both images. I thought of the euphoria and confidence of scientific observation in his early drawings and how it all fell into doubt with melancholic angels and death on horseback after the death of his mother. There are poems that echo such transitions — as difficult as they are — elsewhere in the book, as some of the wonder of my own early experiences begin to take on gravity and tarnish. Paintings do form a great number of the source images of my memory, and they necessarily come into play as I work through how I feel and what I think about the day-to-day moments of my life. I like when these images arrive and inform. I feel close to art in those moments.

Albrecht Dürer, Great Piece of Turf,1503, Watercolour, pen and ink,15+7⁄8 in × 12+1⁄4 inches,Collection: Albertina, Vienna

LY: Throughout this project, you write direct lines that seem to be about an image in front of you, but then later in the poem you destabilize the image world. A good example is the poem “I imagine a horse head.” You spoke about this back-and-forth of looking at painting in some of your answers, but I wonder now if the act of looking has become a method of writing and did it ever hold you back? I believe your current project does not have to do with images. What is it like to write with and without images? What part of collaborating with an artist has been fulfilled and what still needs to happen for you in the future? What’s next?

ES: Writing poems about art is a strange business. Many years ago, I remember setting out to write poems about a particular artist — I won’t say whom — and I thought the work would be generative for writing. I would work every day and I spent many mornings waiting for something to happen. I thought that his works would have to result in poems and I believed in them as though I was waiting for a tree to bear fruit. I would watch and wait. Well, nothing happened and no poems were written, and I have no explanation for this. However, there is a room at The Met with Rosa Bonheur’s Horse Fair, 1855, and Gustave Courbet’s The Source of the Loue, 1865, that I simply can’t walk through without writing a poem. That room needs a poem from me every time. In other words, I am sure that artwork will continue to become poems in my life, though it is difficult to know what those artworks might be. As for what’s next, I have been writing Ghazals, a form that originated in 7th century Arabic poetry, and I am trying to see what I can do with that form, which traditionally is a mode of love poetry. To contemporary eyes and ears, though, Ghazals seem to embrace and investigate a sort of collaged and fragmented state of being. You will be happy to know that while I am writing my couplets, my dozens and dozens of couplets, that occasionally a painting will spring up and enter the poem as an image. Often when they enter a poem, it feels like that old Tumbler feed where one would Photoshop great works of art into ugly rooms. Yet, the more I work with them, the less they seem like disruptors and the more they seem like bizarre windows. I can tell you that I like looking through these windows.

Gustave Courbet, The Source of the Loue, 1864, Oil on canvas. H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929, Metropolitan Museum, New York, New York