Can Images Desensationalise Abortion?

ArtReview / Sep 20, 2023 / by Wendy Vogel / Go to Original

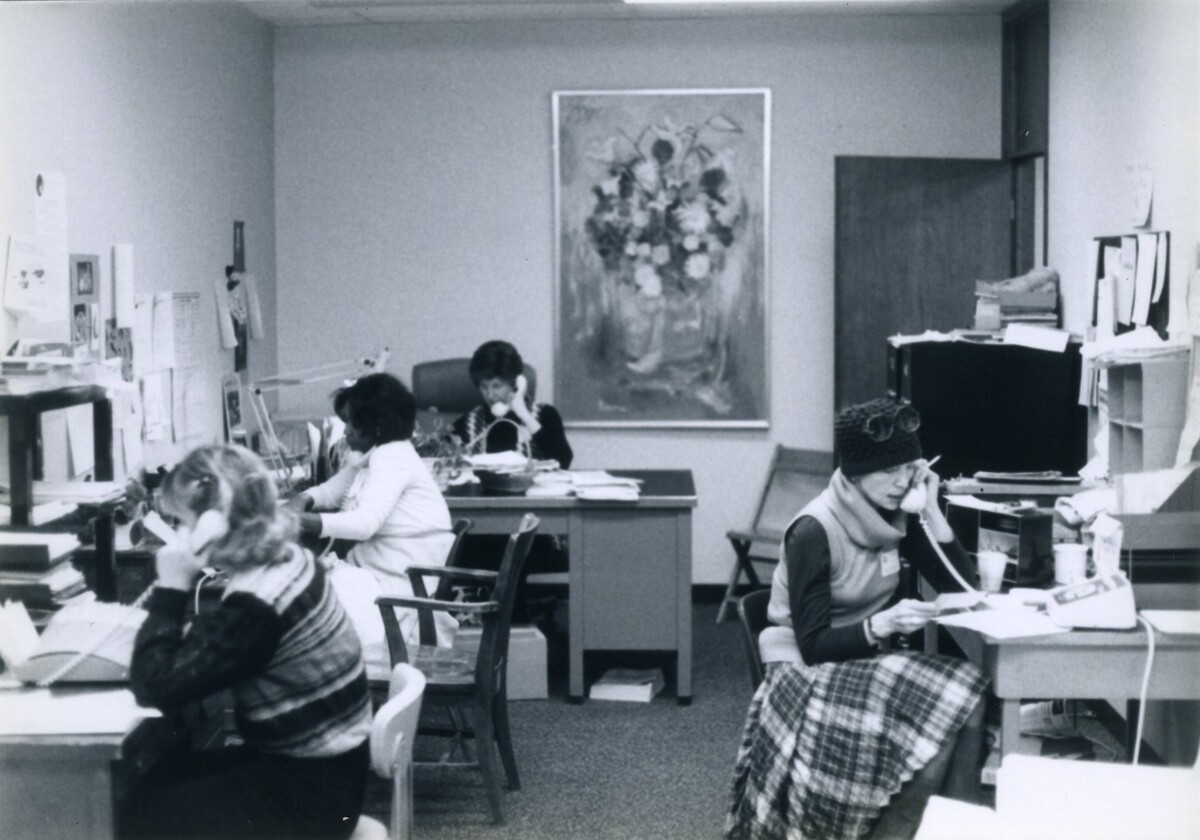

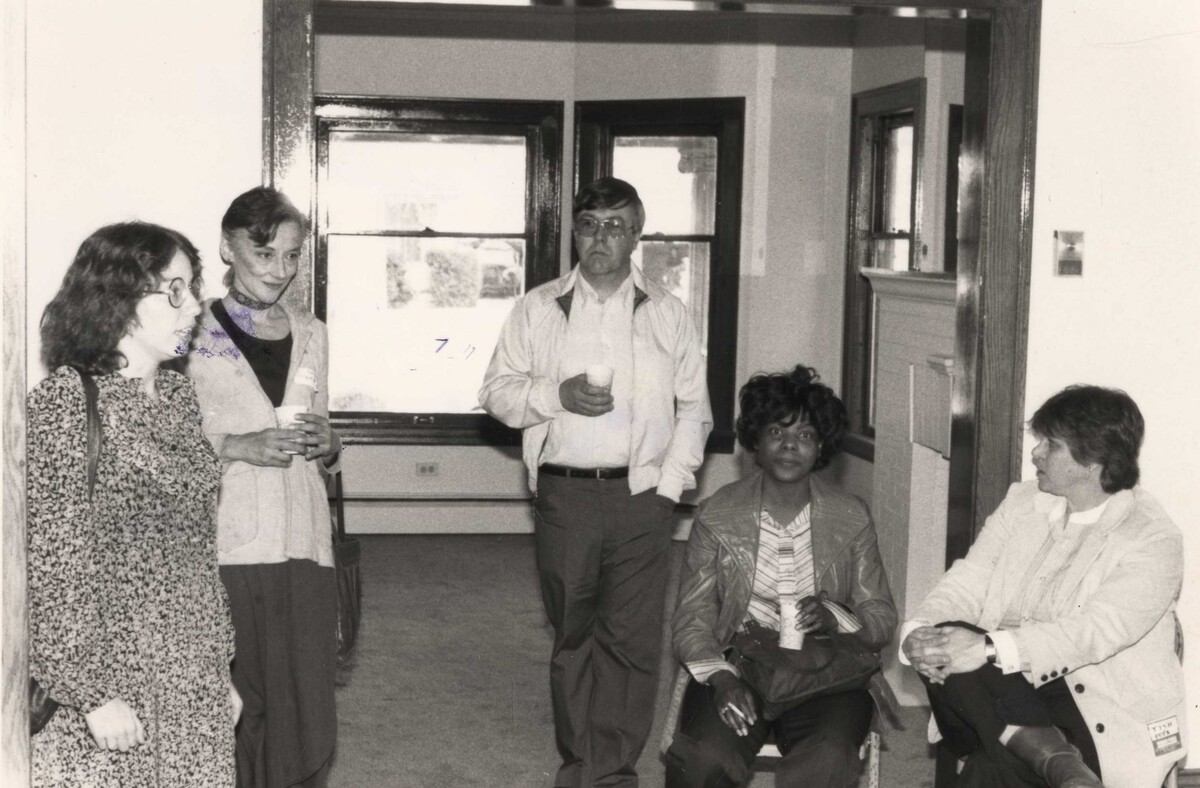

Source material from Carmen Winant, The last safe abortion, 2023. Courtesy Carmen Winant, from Preterm, Cleveland

Carmen Winant’s new exhibition raises the question, what type of abortion imagery is radical now?

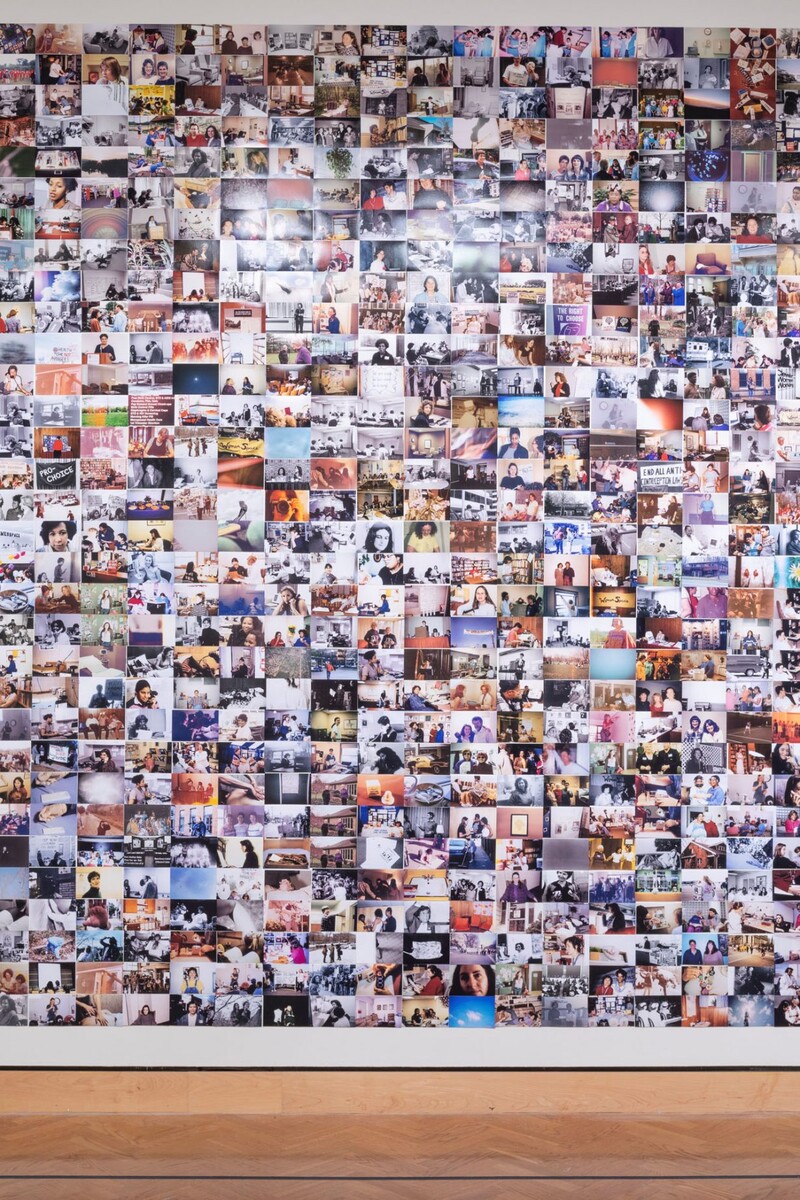

Artist Carmen Winant is known for photographic collages that visualize labour and the feminist networks that support it. My Birth (2018) featured over 3000 images of birthing culled from books, magazines and other printed sources. Then, for A Brand New End: Survival and its Pictures, an exhibition and book produced by The Print Center in Philadelphia in 2022, Winant culled photographic material from the archives of the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence and Women in Transition. Her current solo exhibition at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, The last safe abortion, comprises large-scale collages of new and scanned archival photographs from reproductive health clinics across the Midwest — including Minnesota, where the exhibition is held, and Ohio, where the artist lives. At a time of eroding abortion rights in the U.S., viewers might be surprised at what they see – and don’t see – in these works. What is seen: lots of images of women answering telephones, posing with colleagues and celebrating occasions like birthdays and Take Your Daughter to Work Day. What is not: images of violent protests, anti-abortion propaganda, anguished patients.

The last safe abortion opened in August, just over a year after the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade. Following the reversal of Roe – a legal statute guaranteeing the federal right to an abortion up to foetal viability – abortion has been banned, limited or put at risk in 26 states and three territories. Rather than dramatize the political, religious or philosophical debate of the current war on abortion in the U.S., Winant’s series recognizes the everyday labour of the people who keep clinics running. A large part of that work involves answering the phones – which, as the artist says, are still ringing off the hook – along with other, ‘profoundly un-visual’ organizational tasks. Winant worked on the project for four years, gathering images from university libraries, historical societies, museum collections and clinics themselves. The resulting collages include photos from active medical facilities, as well as now-shuttered spaces. In an interview with Vanity Fair, Winant explained that the title of her exhibition came from real conversations she had with providers across the Midwest. ‘Almost all of them said the exact same sentence to me, verbatim … which was: “We will offer the last safe abortion in blank” – Ohio, North Dakota, Indiana.’ (Minnesota, where the project is currently on view, is one of the region’s most liberal states; it has codified abortion protection into state law.)

Source material from Carmen Winant, The last safe abortion, 2023. Courtesy Carmen Winant, from Preterm, Cleveland

With the encouragement of the exhibition’s curator, Casey Riley, Winant also shot photographs in three clinics located in Ohio, Minnesota and Iowa (though the artist trained as a photographer, she has not incorporated her own imagery in a project for years). In a loosely gridded collage are multiple images of clocks, waiting rooms, office workers, medical staff sterilizing equipment and airplane views. The composition breaks down linearity in favour of a mind-map-like arrangement of photographs. The result encourages the eye to take in the scene holistically. While the timepieces intone the countdown clock to abortion access – the number of weeks one is pregnant, mandatory waiting periods, the amount of time before a state restricts access – the straightforward look of the pictures also evokes a timelessness.

In a phone call, Winant explained that the project was ‘a way to countermand the anti-choice visual propaganda that weaponizes photography’. Her creation of an alternative visual archive of abortion connects the project with her earlier works. But the images’ neutrality feels strategically calibrated to today’s political climate. In May 2023, the Lewis-Clark State College in Idaho censored an exhibition featuring several artworks about abortion and reproductive health. The exhibition, titled Unconditional Care: Listening to People’s Health Needs, curated by the artist Katrina Majkut, reopened at the Rochester Contemporary Art Center in New York this month. Furthermore, Winant’s work aligns with second-wave feminist art that visualizes care work historically ignored in art. Consider Mierle Laderman Ukeles’s decades-long commitment to highlighting domestic and sanitation labour, which she outlined in her Maintenance Art Manifesto of 1969. (Key line: ‘After the revolution, who’s going to pick up the garbage on Monday morning?’) Or Chantal Akerman’s film Jeanne Dielman 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), depicting the real-time domestic labour of a widow and single mother – monotonous until it’s not.

What does it take to convince others of the radical stakes in this fight for reproductive justice? In 2020, two years before the repeal of Roe, I mustered my own attempt at raising consciousness in an article about a spate of recent exhibitions that addressed reproductive rights and abortion. I grounded the story in a narrative about my personal experiences as a volunteer Planned Parenthood patient-escort in Houston, Texas, circa 2010. At the clinic, I came face to face with the vocal – at times terrifying – anti-choice protestors. In my article, I juxtaposed my memories of clashes with protestors against artworks that offered a new, different visual approach to pro-choice discourse. Historically, images of abortion have been dominated by metaphor on the left – from the no-more-coat-hangers graphic to the subtly stigmatizing 1990s slogan coined by Bill Clinton, ‘keep abortion safe, legal and rare’. The right has favored gruesome pictorial strategies focused on fetal personhood. The artists and exhibitions addressing the topic circa 2020, in my article, had crafted bold slogans countering shame around the procedure: Abortion Is Normal, Shout Your Abortion, Thank God for Abortion. Winant’s project builds on this legacy, with a more sober tone.

Carmen Winant, The last safe abortion, installation view at Minneapolis Institute of Art, 2023. Courtesy Minneapolis Institute of Art

Before speaking with Winant, I revisited some older documentary Carmen Winant, The last safe abortion, installation view at Minneapolis Institute of Art, 2023. Courtesy Minneapolis Institute of Art | Pervious Page material on the U.S. reproductive justice struggle, including the PBS Frontline episode ‘Abortion Clinic’ from 1983. Filmed just ten years after the Roe decision legalised abortion, it was the first U.S. television programme to show an abortion procedure. Despite its journalistic both-sides-ism – the footage includes interviews with religious anti-choice activists, as well as pregnant people who choose not to terminate – it was one of the most radical and graphic televised representation I have seen of the topic.

The episode features the Reproductive Health & Counseling Center in a Philadelphia suburb. Located in a former library, the clinic is full of period-era mismatched décor – a small rainbow mural, several different swatches of patterned wallpaper, shag carpet; no security guards, metal detectors or bulletproof glass. The patients counseled are young, mostly single, financially insecure women, often interviewed without the presence of parents or guardians. The youngest person in the film to terminate her pregnancy, Barbara, is a 17-year-old freckle-faced mother of a two-year-old. The cameras follow patients from their intake counseling to the process of undergoing a vacuum-aspirated abortion, seemingly without anesthesia, in a clean but minimal procedure room. In today’s polarizing climate, it’s hard to imagine such an unflinching, medicalized look at the procedure – on national television.

This raw piece of TV journalism sought to expose the realities of abortion at a time when the anti-choice movement was gaining power under Ronald Reagan’s administration. Forty years later, in the wake of physical and symbolic violence against providers, it is easy to see how such an earnest journalistic project could be sensationalized by that movement. Winant’s photographic project, by contrast, presents a mundane look at the work of abortion clinics as healthcare in high demand. But there is radically in its conviction without the need to moralize, and its interest in highlighting the workers who are often unseen. Although Winant considers her work distinct from documentary, she says, ‘I’m interested in making something that feels serviceable’. In this project, what seems most serviceable is the proliferation of images – thousands, across decades, attesting to the healthcare work that has been performed throughout history, and will continue, in networks of organized, feminist care.