Artist Charisse Pearlina Weston: ‘This is a kind of violence that’s been naturalised, but it’s not natural’

Financial Times / Apr 26, 2024 / by Maegan Dolan / Go to Original

Portrait of Charisse Pearlina Weston, shot for the FT by Stephanie Mei-Ling

Charisse Pearlina Weston grew up in Houston, Texas, near the birthplace of rhythm and blues label Duke/Peacock Records, and it was while listening to its artists that she developed a deep appreciation for the blues cover. She loves how it can feel like a radically different song depending on who’s singing it.

“I think maybe [blues covers are] one of the things that got me really interested in repetition, in the way that a return to something is not a recuperation, but it’s actually an opening out into another space . . . It opens up sonic possibilities,” she says when we meet at her studio in Harlem, a five-storey red-brick building that housed breweries until Prohibition shut them down.

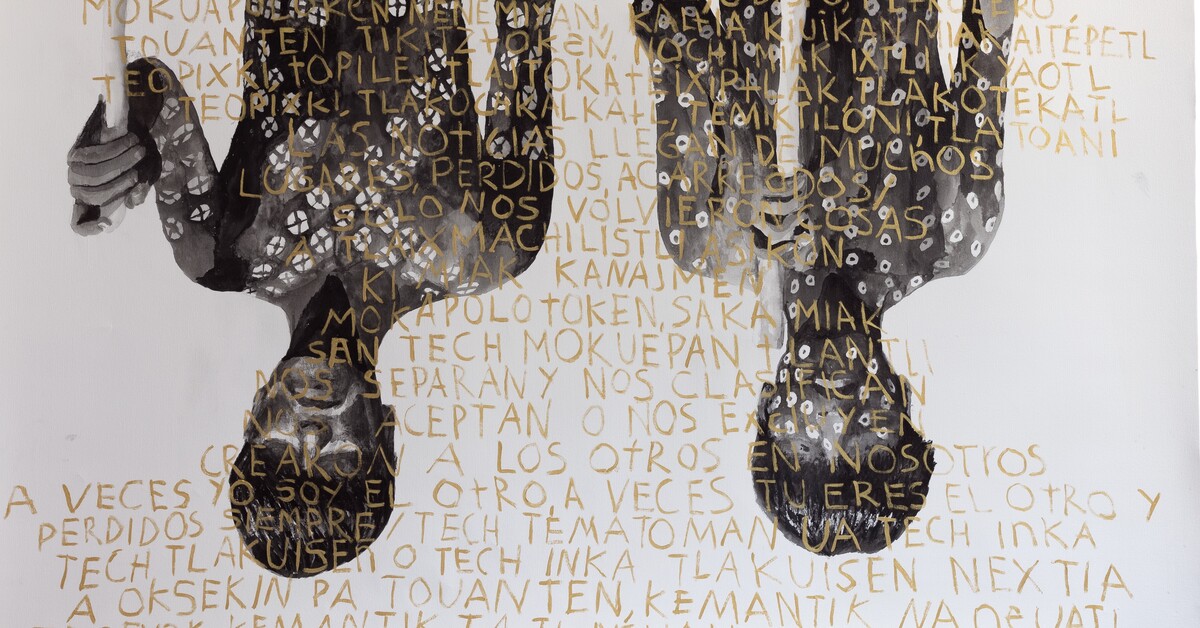

These volatile possibilities are visible in Weston’s work, which often uses glass in precarious ways. In the current Whitney Biennial, panes of glass are strapped together to form one large panel hanging from the ceiling at a steep angle, disrupting movement through the gallery space, while in a group show at MoMA PS1 Weston’s smaller-scale sculptures counterpoised slumped (heated then moulded) glass, lead, concrete, etched text and photographic stickers. Her work will also be at Frieze New York with Patron Gallery.

‘of [a] tomorrow: lighter than air, stronger than whisky, cheaper than dust’ (2022) by Charisse Pearlina Weston © Courtesy the artist/Queens Museum. Photo: Hai Zhang

In her work, Weston returns to historical images and text, but the way she replays these references is more like a blues cover than a plain rendition. She morphs and distorts archival images and text, enfolding, layering and deconstructing them into urgent, emerging forms. Her intent is not to replay the past but rather an act of awareness that the past is being replayed in the present: “I’m using the fact that this keeps happening over and over again to remind us that this is a kind of violence that’s been naturalised, but it’s not natural.”

Weston studied painting and art history as an undergraduate before shifting to conceptually focused work. She had returned to Houston and fell in with a group of supportive artists who were interested in installation and social practice. “I never thought of myself as a sculptor until I got to grad school and realised that I was really interested in the way that sculpture can transform and manipulate the spaces that we’re in.”

In her Harlem studio, she is working on a new series of sculptures that use two-way mirror glass, the sort in interrogation rooms so a witness or suspect can be spied on. When she heats the glass in the kiln to collapse and mould it, the glass becomes opaque and the new shape has an iridescence, appearing oceanic and fluid. Weston has been interested in playing with transparency and opacity since she began working in glass in 2016. Perhaps making the glass opaque is a poetic gesture: opacity is a form of resistance.

‘of an intimacy who leaps and whirls within the warring of itself’ (2023) by Charisse Pearlina Weston © Courtesy MoMA PS1/The Studio Museum in Harlem. Photo: Kris Graves

‘breach (a notion of freedom)’ (2019) by Charisse Pearlina Weston © Photo: Paul Salveson

Weston was already using sheets of glass in her work when the Black Lives Matter movement was dominating the news; she had started thinking about how you might represent the constant risk of violence and the omnipresence of anti-Blackness after the death of Sandra Bland in a jail cell in 2015, a woman close to her age who grew up near Houston. “There was something about glass . . . with so many contradictions embedded in this material’s structure, that made it feel like it could represent both the risk of anti-Black violence and also this capacity for shape-shifting and moving beyond, in-between it.” She began moulding the glass and hot-folding by hand, a process that “imbues a risk of precarity, which mirrors the anxiety of the Black experience in the US”.

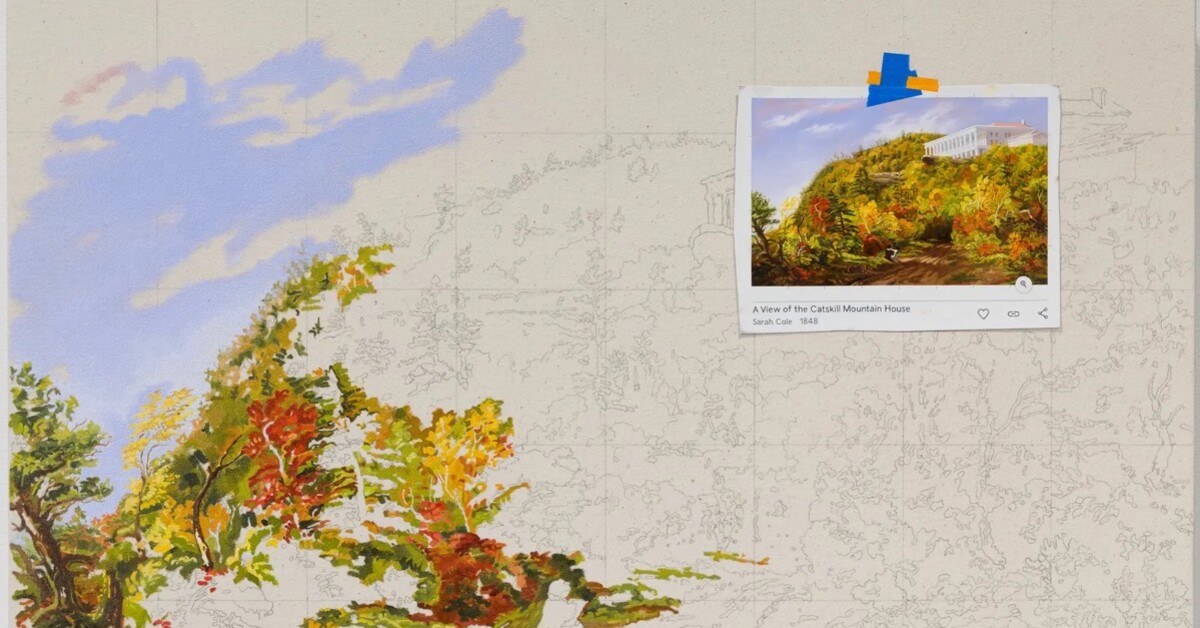

Some of Weston’s sculptures evoke the loose organic forms of architect Frank Gehry’s maquettes — the way the eye is led along a shape’s edge, like a path drawn in space. When I suggest this, she smiles as she remembers her studio in Irvine, California, where a small gap ran in the floor from wall to wall. One day, she balanced sheet glass in the deep divot, installing a translucent wall across the room. The glass edges caught the sunlight and drew long, linear shadows on the floor, which she photographed, printed and began to work on again, carving with broken glass and affixing crushed glass in geometric shapes, further abstracting the refractions into something expressionistic, which refuses legibility.

Detail of ‘An Appeal, but, in Particular, Very Expressly, To (i sink)’ (2019) by Charisse Pearlina Weston © Courtesy the artist. Photo: Paul Salveson

And so we return to music: these two-dimensional works are named after blues songs. Weston says: “I feel like [the blues] is so important in terms of being an expression of a certain kind of Black intimacy, Black interior life.” Without hesitation, she says her favourite blues singer is Bobby “Blue” Bland, a 1950s Duke recording artist (more recently sampled on Jay-Z’s 2001 album The Blueprint).

Weston describes some of her works as “analogous to a blues moan that can’t be held back”. The historical weight and political concepts reverberating around her during the creation process contain an urgency that she must voice. “We as artists are not here to give people answers. We’re here to help people ask questions — questions they might have never asked.”