Jen Bervin and Dianna Frid

BOMB / Sep 15, 2016 / Go to Original

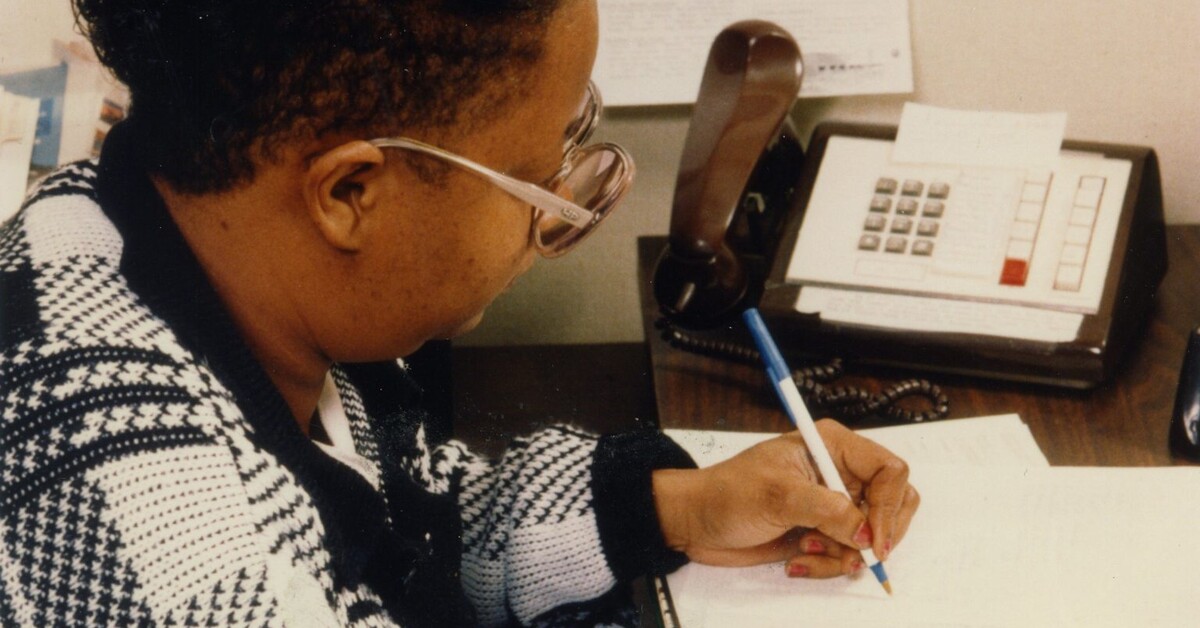

Dianna Frid, NYT. APRIL 24, 2014, RICHARD H. HOGGART, 2014, embroidery floss and graphite mounted on canvas, 15 × 20 inches. Photo by Tom Van Eynde.

Restoring, overwriting, removing, and color-coding are just some of the actions that come to mind looking at the interdisciplinary works of Jen Bervin and Dianna Frid. Each in her own way explores the intersection of text and textile, where writing is a physical, intimate gesture. Both artists employ embroidery, sewing, and weaving to craft works that test the boundary between the visible and the legible.

To immerse oneself in the projects of Bervin and Frid is to be reminded that poetry lies in wait—in dusty Latin tomes, in ornate capitulares, in New York Times obituaries—to be revealed through radical acts of transformation. Their practice is one of palimpsest, in which existing text is repurposed through a combination of buildup and erasure to uncover what is essential.

Frid creates sculptures, installations, and artist’s books, often involving found text and archival material. Her recent book, Apuntes, thread-annotates photographs of classical Greek and Roman sculpture with suggestive pattern diagrams from weaving manuals.

Bervin’s work includes performances, drawings, and conceptual projects. She has published nine books, including Emily Dickinson: The Gorgeous Nothings (Christine Burgin/New Directions, 2013), the first full-color facsimile edition of Dickinson’s manuscripts.

The artists exchanged studio visits on the occasion of Bervin’s latest project, Silk Poems, a work written in nanoscale in the form of a silk biosensor, on view in Explode Every Day at MASS MoCA through April 2017.

—Sabine Russ

Jen Bervin

Is it fair to say that you make inexplicable work about knowledge?

Dianna Frid

(laughter) Yeah. That’s nice. It makes me think of Lucretius and his poem “De rerum natura.” He found a way to describe natural phenomena and the forces that shape them not as the result of divine intervention but as part of a larger dynamic system. The fact that he chose to do that through poetry reminds me of what you often say: “Poetry has work to do.”

JB

You use a Lucretius quote in that beautiful piece Be Made of Laughing Particles.

DF

“Surely a man can laugh and not be made of laughing particles.”

JB

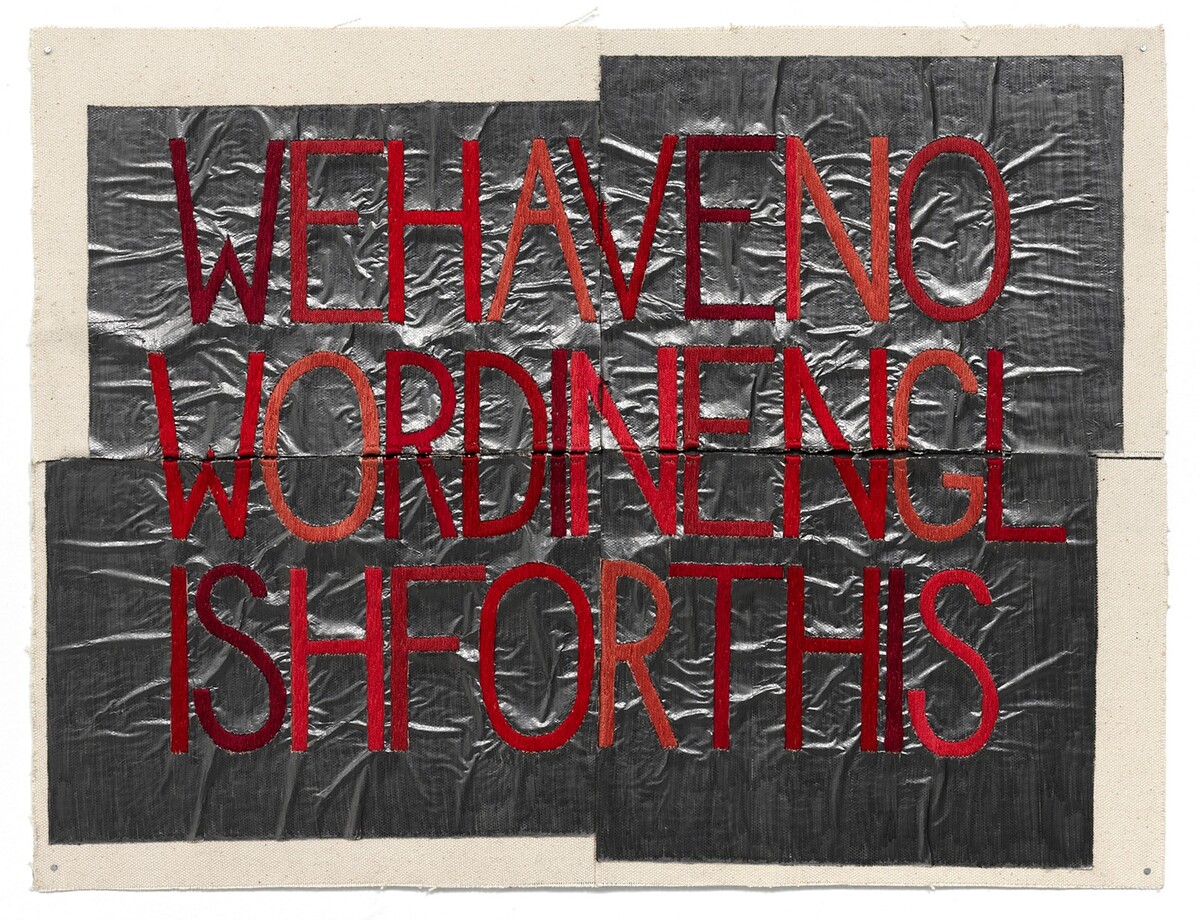

Yes, I love that. I’ve noticed how you foreground the inexplicable in what you choose to excerpt. For instance, “WE HAVE NO WORD IN ENGLISH FOR THIS,” from your series Words from Obituaries, taken from a New York Times obituary of Richard H. Hoggart. The full sentence reads: “We have no word in English for this act which is not either a long abstraction or an evasive euphemism, and we are constantly running away from it, or dissolving into dots.”

DF

The word in question is the word fuck. Hoggart was a British professor of English and a star witness in the trial of D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover. He spoke the words you’ve just cited when defending the publication of an uncensored edition of the novel. For my series Words from Obituaries, which I describe as text embroideries on graphite, I devised a color-coded system to classify the lifework or profession for which the recently deceased will be remembered. I use grays for war criminals. Blue is for doctors, healers, and psychoanalysts. I haven’t made any in brown yet, but it will be for historians and journalists. Pink is for anybody who worked with language—publishers, poets, novelists, linguists, authors, and translators. Red is for educators. Purple is for entertainers who were not artists, and these include athletes, entertainment agents, and other kinds of impresarios. Orange is for artists, designers, musicians, but not writers.

JB

Yellow is the largest section on your chart.

DF

Yellow is for dissidents, activists, and humanitarians. But a humanitarian can also be a writer or a doctor or an entertainer. Lifeworks overlap. In classifying, I’m also alluding to the absurdity of classification, because no one is reducible to just one thing. All systems start out idiosyncratically. Think of planetary nomenclature, for example.

JB

In your chart, the series title, Words from Obituaries, is in purple—for a performer or an athlete?

DF

Words from Obituaries is an endurance project! (laughter) I’ll probably be working on it for the rest of my life. On Kawara is a model.

JB

Do you at some point start mixing colors according to ratios?

DF

No. That’s where the voice-over—my term for the voice in your head that’s frequently nudging you with directions—says, “Keep it simple, otherwise there are too many options.”

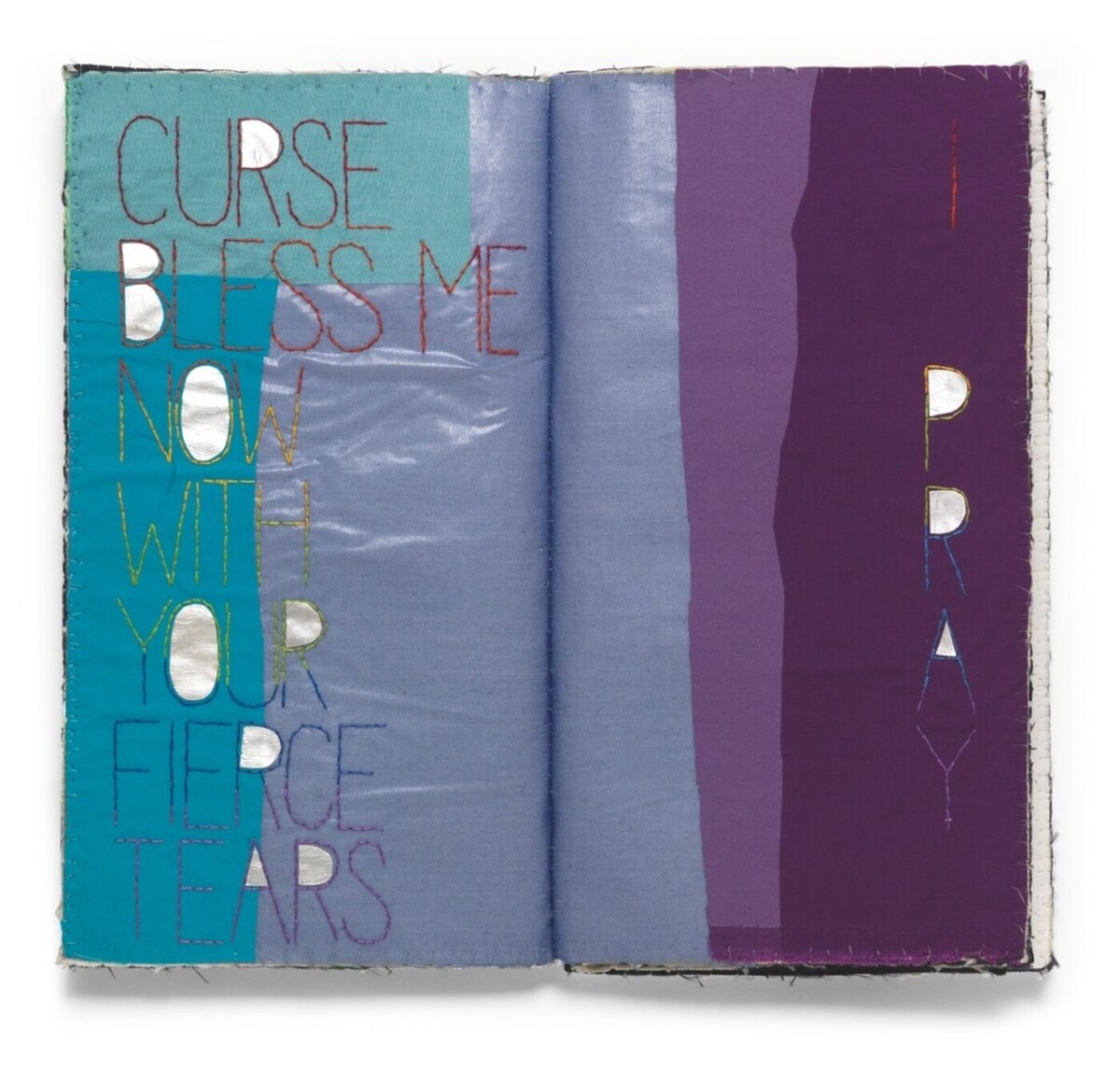

Dianna Frid, from Against the Dying of the Light, 2010, cloth, aluminum, paper, thread, and paint, 8 × 6 inches (closed), 9 × 11.75 inches (open). Photo by Tom Van Eynde.

JB

When you’re plotting out your excerpt in your notebook, I see that you count letters. This seems to relate closely to prosody, but also to spatial considerations when you’re embroidering the phrase. Do different letters count differently?

DF

No, only by necessity the letter I counts for less because it takes up less space.

JB

Do you have a character limit for these works?

DF

More or less. The longest one so far is thirty-seven characters: “ITS OUTSIDERS AND OUTLAWS NOW MORE THAN EVER.” That’s from a Harry Crews obit. He was a fierce novelist and essayist I didn’t know before I read about him. The original was: “The literary world needs its outsiders and outlaws, now more than ever, and with Mr. Crews’s passing there are very, very few of them left.” It’s the only obituary related to this ongoing project that has made me cry.

JB

There’s solemnity in the series, but also humor. It feels piercing, but it resists being only about death.

DF

At first, I resisted the funny ones. For example, “HIS LAST WEBSITE” was one of the earliest works. I couldn’t look at it, and had to put it away for the longest time. I felt that it was an insult because it was funny. Hillman Curtis was a noted new media designer, and he died very young.

JB

I appreciate the way you use enjambment in Words from Obituaries—the way it slows reading and renders the words mysterious again.

DF

This happens especially within a single word, for example, in “OF FIRE IN WEIGHTLESSNESS,” an excerpt from the obituary of Janice Voss, a scientist and astronaut who studied fire in zero-gravity environments. It is very difficult to read because of the enjambment at the letter G.

JB

It brings me back to the experience of first learning to read, of the word itself being mysterious, and maybe not quite legible. Similarly, in your artist book Against the Dying of the Light, when the interior space of the letter is filled in, like the inside of an R, I experience the kind of reverie that I slip into when doodling or sewing.

DF

Ah reverie! Sewing by hand is physical. The repetitive act of making can be trance-inducing and meditative. Of course, I’ve done the opposite, too, and I’ve damaged my back from sitting for hours. Repetitive activities can also become boring and frustrating. But in the best of moments I’m able to lose the self.

JB

I wanted to ask you about how you structure sewing. You refer to it as a rhythm. Do you have certain rules for how you go about it?

DF

The rhythm changes if I’m interrupted, so I thread a lot of needles and have them all ready to go to avoid interruptions. When one length of thread is used up, there’s another one right next to it. To be honest, sometimes when I start, I’m already in a state of interruption because I’m so agitated or anxious with anticipation. It takes a while to interrupt the interruption, to get into that space of breathing.

JB

For me too. Soon after I finished making River—the 230-foot hand-sewn scale model of the Mississippi in sequins—I realized that I had a new problem on my hands. For ten years, whenever I needed to calm down, to quiet my mind, I’d sew it for a while. When it was finished, I lost that kind of time. Most of my projects are cerebral research projects, so I need a new River!

Jen Bervin, River (detail), 2016, sequins, tyvel, mull, and thread, 230 feet (curvilinear). Photo by Charlotte Lagarde.

DF

There’s a purgatory called “being between projects.”

JB

There is. When I first came to your studio I noticed that there’s a choreography of stations going on in here. Can we talk about that large mixed-media work over there?

DF

It’s called Weave, and it’s fairly new. It was going to be a book when I started. You can still see the structure of the pages in the structure of the field where the components are located.

JB

It has a medieval manuscript feel because of the serif letters and—

DF

—the capitulares! What are they called in English?

JB

Drop caps.

DF

Yes, thanks. Historically capitulares were at the beginning of a section, and they were decorated and framed in their own space, often a rectangle within the field of the page.

JB

It feels like something is breaking open in that piece. Is it still in process?

DF

No, it’s finished. This is an example of a work telling me what to do. It went through many lives, but it needed something for a long time. And I figured out that it needed the bands of the warp, of cloth made in the loom.

JB

There’s also so much reflective light.

DF

It is because of the aluminum foil; I keep coming back to it as a material—it’s mirrorlike, but it’s not a mirror. It changes when you stand in front of and around it. A couple of months after I started what I imagined was going to be an artist’s book, I figured out that the piece couldn’t be that when it didn’t flow as a sequence. Basically, it spelled out a word broken into several spreads. But that was not enough of a sequential experience. Ulises Carrión, in “The New Art of Making Books” (1975), talks about how a book is a sequence of moments. It can be akin to a cinematic experience of time, even if the book operates like a collection—think Ed Ruscha. This unfolding over time was not working with what eventually became Weave. I more or less had to plunge into the unknown in order to rescue what I had. I used the embroidered serif letters but fragmented each one by splitting them from within the grapheme and placing them farther apart from each other. I was guided by basic nonverbal formal problems that never go away in making work. No matter how conceptual one gets, the problems of form and matter carry through. In the best moments, they contribute to the irreducibility of the experience of a work.

Dianna Frid, Weave, 2015, embroidery floss, aluminum foil, paint, and cloth on paper, mounted on canvas, 78 × 60 inches. Photo by Tom Van Eynde.

JB

It’s so exquisite, what you’ve done.

DF

It has been helpful to notice that I’m terrified when I am working without a system. While a system gives you a sense of direction, sometimes it’s also helpful to say, “There is not going to be voice-over.” In addition to a voice in the vicinity of your head, a voice-over can also be another’s perceived authority telling you what to think about a work through an ancillary tag rather than through your own experience of it.

Think of Forrest Bess, whose work is perhaps along the same vein as Hilma af Klint’s. Or Richard Tuttle at his best. There seems to be something other than a voice-over guiding their works. I’ve had moments when I’ve felt a little bit of that.

JB

One writer mentioned Arte Povera in relation to your work, and I thought that reference seemed so right.

DF

Yeah, for sure. There are two artists from that movement whose works are very important to me, but so different from each other—Giuseppe Penone and Alighiero Boetti. In the case of Boetti one could immediately think of embroidery as a connection, but for me it’s more that he recognized how a village of Afghani artisans he employed could bring into focus the modularity of letters in relation to textiles. That’s a text-textile connection. And in the case of Penone, it is in the clear relationship of how the body of the artist gives form to matter, and, one could argue, vice versa.

Then there is the Brazilian artist Mira Schendel. Maybe her work arises from a system, too, but when I first saw her floating letters at The Drawing Center in the late ’90s I was blown away. They are mystical! But you know that. I’m not trying to make a binary between having a system and having no voice-over. For me it’s just helpful to allow the work to gestate in the space of the unknown.

JB

If you had to think of two works you’ve done that exemplify the spectrum between having a system and not having one, which ones would you point to?

DF

Words from Obituaries is system-based, although there are variables. At the other end of the spectrum would be my book Ranuras, which is Spanish for “furrows,” or “grooves.”

JB

Can you say how?

DF

Not having the voice in my head is terrifying, yet important. It means that I might change my mind late in the process and begin again because what I thought was important at the beginning later falls away. Ranuras had two beginnings—I made it twice. I can’t even remember what the process was other than I had just been researching the collection of the Francisco de Burgoa Library in Oaxaca for an exhibition, and I had to begin to think through all the books that I’d examined while I was there. Most of them were in Latin or archaic Spanish and dealt primarily with premodern and early modern science treatises from Aristotle to Diderot and beyond. I was paralyzed at first and simply had to start with something. So I got busy and I knew that if Ranuras failed as a book, I would start again, and, if necessary, again after that. The title “cracks” or “furrows” gave me permission, however terrifying, to admit that there could be cracks or unwelcome intrusions in my own process.

JB

Ranuras is not a text-based work; it is pictorial. Weave, on the other hand, is hard to describe as simply text. There is no syntax because the letters are split, and one can imagine that other letters are mixed inside existing ones in a way that you hadn’t done before.

DF

Part of it was an accident. Sometimes intention comes into play after something unconscious is made manifest. I’m not ascribing intention to the inanimate object, but the work has an intention, so to speak, that exceeds my own.

JB

Not being able to read what Weave says, I work so much harder to come up with words: I keep reading “empathy,” in the upper part, though I can’t point to how I come to that.

DF

It’s important that I never reveal the word, because that would stop its potential to be always different, always something else. Allowing myself to break open a word by splitting its graphemes was like passing through the combinatory space of all the letters in one word to all other possible words.

JB

That moment when you can’t recognize a word is so much like the shift from one language to another. When you’re first learning a second language, you’re mystified at what you’re hearing—recognizing some things and not understanding others. You’re paying a lot of attention because you’re trying to get your bearings. For your show in the Burgoa Library, you switched to Spanish?

DF

Spanish is my first language, but I used it here for the first time in my adult life as an artist.

JB

Will that continue?

DF

I don’t know. I’m in love with the English language. It’s so succinct. I imagine you know this well as an artist and a writer steeped in this language. This brings me to your own writing and your recent work. What was the genesis of the Silk Poems?

JB

A writer I know wrote a piece for Slate on new scientific and technological uses for silk. This fiber has been used for 5,000 years, but it can now exist in a liquid state, and the medical potential for it is huge because it’s universally biocompatible with the human body. Knowing that I often work at the intersection of text and textile, the writer contacted me to see if I might be interested in collaborating on something. So we went to visit the silk lab at Tufts University’s biomedical engineering department. It was quite a revelation. One of the things that struck me was that silk film is being developed as a bioactive sensor. Using nano-patterning as an optical device—the same way a butterfly wing changes color in the presence of a drop of acetone—silk can register a visual change. A year later, I was still thinking about what might be written in silk at that scale inside the body. I wanted my approach to such a tiny sensor to reflect the long intercontinental history that shaped silk culture, and I wanted to trace it myself. What you can get in a library or an archive is different from what you can get if you go to a place. I wanted all of it.

DF

So you wanted the research and also the encounter on site, the travel?

JB

Yes. A Creative Capital grant made it possible to visit over thirty international textile archives, medical libraries, and sericulture sites in North America, Europe, the Middle East, and Asia. I learned that the development of silk keeps pace with the rise of the earliest languages. You find words for silk as early as Oracle script, which was the first written language in China, used largely for divination.

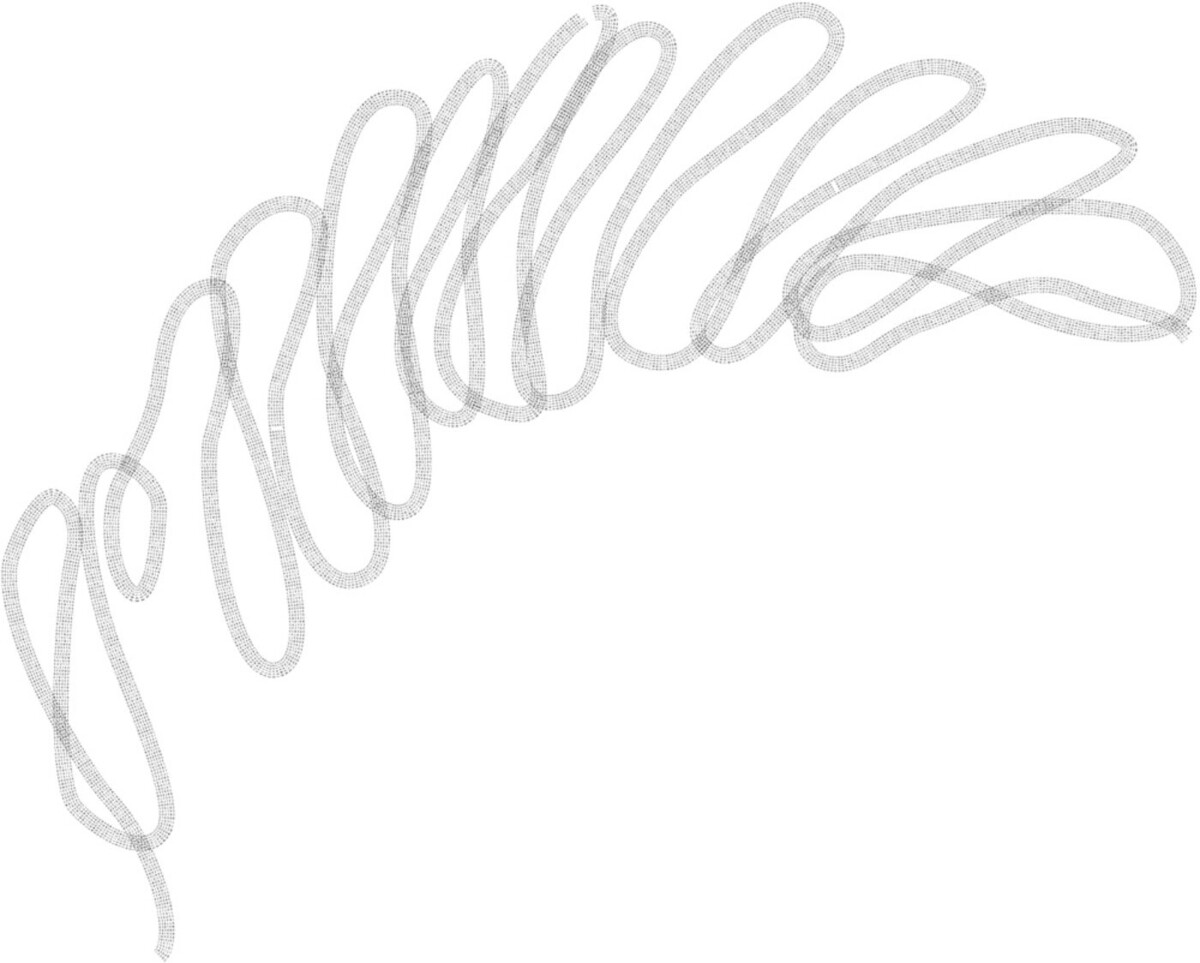

Jen Bervin, poem strand modeled on cocoon writing, from Silk Poems, 2016. Typeset by Heather Watkins Studio.

DF

Jen Bervin, poem strand modeled on cocoon writing, from Silk Poems, 2016. Typeset by Heather Watkins Studio.

You mean the I Ching?

JB

Even earlier. Oracle script is primarily written on bone or plastron, the shells of turtles, and it’s carved—an incised language. There are characters for silk, silkworm, silk cloth, and so on that go back to the eleventh century BC. I play with that in the poem because the Chinese radical for silk, 絲 (pronounced sı¯), precedes something like 300 words in Chinese.

DF

Do the silk membranes offer us possible new locations for writing or inserting code into the body?

JB

The gold letters of the poem on my silk film are based on new biosensor transmitter technology. To my mind, the ideal recipient of the poem is a person who needs the sensor to monitor a serious medical condition. I wonder what a silkworm would have to say about this protective thing it made with its body inside another. Here’s this creature whose entire existence is predicated on transformation, on cycles of living and dying.

Silkworms cannot survive in the wild and they require considerable human care. They live about a month and eat an astounding amount of mulberry leaves during their five instars—humans grow and harvest leaves for them, chop the leaves fine for the newborns, and clear the shit the worms produce. If the pupa isn’t stifled in its cocoon to preserve the filament, if it’s allowed to emerge, it lives three weeks longer at most. But the silkworms can’t fly, they only flutter. In the poem, the silkworm’s perspective is that “a wing is a thing that gets you there.” They want to find their mate and have sex before they die. I was thinking of their in star cycles as small rebirths and deaths—going to sleep and waking up days later in an old skin with a new skin inside of it.

Detail of Silk Poems, 2016, nano-imprinted gold spatter on silk film. Photo by Bradley Napier.

DF

I love that! The poem is made with the body of a creature who makes the silk on which it is inscribed! And then there is the human body! You’re thinking of the poem as implanted in the body of a person and what it would be to live with this poem inside your body.

JB

A close friend of mine is going through chemotherapy at the moment, which destroys cells in the body. Silk is not like that—it’s completely biocompatible. We like it, and it likes us. If you’re ill, monitoring your health with a silk biosensor under your skin occupies serious mental energy. It would be so much better for the mind and spirit to have something bringing other values and qualities to that space. That’s really how this idea originated, as an added protection in a spiritual way.

DF

Are you thinking of it as a talisman?

JB

Yes, as a layer of protection for the mind but also as a carrier for a tremendous cultural history. It’s a tiny sensor, but the Silk Road spans a quarter of the equator.

DF

Are you nano-inscribing the film? Or are you writing or typing?

JB

I’m writing the poem and working with a designer to format it. After that, I work with scientists at Tufts who will nano-fabricate it. The strand design resembles a weft thread or a beta sheet. Its pattern comes from a photograph of how the silkworm lays down its silk filament in the cocoon, and the enjambed six-letter line comes from the DNA repeat so that the poem’s form draws from both.

DF

So one has to read in a boustrophedon sense, that is, in both directions?

JB

Yes, the strand line, which is printed at a very tiny scale, folds and reverses. To read it, you have to use a microscope.

Image of filament as written by the silkworm in its cocoon, from Silk Poems, 2016

DF

Will there be a reading experience in another form?

JB

Yes, you’ll encounter two forms of it in the exhibition Explode Every Day: An Inquiry into the Phenomena of Wonder, at MASS MoCA. There’ll be the poem encoded on the silk film and the poem in the form of a book, along with a video by Charlotte Lagarde about the research process.

DF

I can’t wait to see it. What are you working on next?

JB

I’m really excited about giving my full attention to Su Hui’s Reversible Poem. During the silk research in Suzhou, China, I came across Su Hui’s poem, “Xuanji Tu,” a reversible poem that has 7,000 possible readings, written by a woman in the fourth century. The original, an embroidered poem, has been lost; it’s primarily known by the story associated with it: Su Hui’s husband had taken a concubine and relocated far away for work. She sent him this poem as a letter—both brilliant and effective, it brought him back, alone.

DF

That embroidery poem clearly had a job to do.

JB

Sure did! It’s one of the most complex poems ever written, and one of the earliest recorded by a woman. It’s just so big and marvelous. It needs its own space. Next year, Charlotte Lagarde and I will be back in Suzhou to follow three Chinese embroidery masters—women of different ages—as they read, discuss, and embroider Su Hui’s poem in a highly specialized double-sided silk embroidery technique at the Suzhou Embroidery Research Institute. From that year-long experience, we plan to create an installation with audio, film, and textile components and a Su Hui book.

DF

The writing that I know of yours is writing you do on preexisting works by other authors. Are there instances where you’re writing the whole text?

JB

Some of my poems are contextual, created directly within specific preexisting texts. Nets is written within Shakespeare’s sonnets, The Desert within John Van Dyke’s prose meditation on natural appearances in that landscape, and while others like The Silver Book, A Non- Breaking Space, and Silk Poems come from a vast swath of aggregated thoughts, speech, and writing—mine and others’. Poems created from preexisting texts have come to be known as erasure poetry, but I dislike the term. It bothers me because I’m trying to make poems that point to the fact that many voices can be present in a text. I find the idea that we write alone laughable, even egotistical. Poetry is a palimpsest that has been endlessly rewritten—it’s a social space we share with others.

DF

Etymologies alone point to that.

JB

Absolutely. And archives. A palimpsest is literally a skin that has been written and rewritten.

DF

You mentioned that your work’s existence in the archive is as important or as necessary to it as its place in exhibition spaces.

JB

It’s a relief to know your work lives in a place where others can find and read it; that it’s being conserved, cared for, and exhibited there. I feel at home in libraries and remain in awe of their potential. How did you approach your show in the Oaxaca archive?

DF

When I went to Mexico to do research at the Burgoa, the librarians were perplexed that somebody would be interested in books they could not read, since the books were mainly in Latin. How do we relate to the past through materials, not just texts that are left behind to be reinterpreted through the lens of our time? In your work I find reassurance that spaces known as archives matter; they’re kept alive in this posthumous intergenerational correspondence.

JB

You often get asked about the relationship of embroidery to women’s work, and you’ve said you’ve had an observation. What is it?

DF

I have a retort, yes, for when somebody tells me that my work, or “this kind” of work, is “feminine.” Regardless of the tone of the question, I’ll simply say, “Yeah, it’s feminine!” There’s a formidable history and an important lineage of women’s work there. But when it comes down to it, the spirit of making something manually, meditatively, and slowly, at times, by necessity, is not about gender or sexual identity. It’s a human need.