In Her Latest Exhibition, Brittany Nelson Searches For Connection Everywhere From Mars to Montana

Cultured / Feb 7, 2024 / by Paloma Baygual / Go to Original

“I can’t make you love me” at Chicago’s PATRON Gallery offers a unique exploration of the parallels between space exploration and queer identity.

“The two dominant feelings that I have grappled with, especially in my formative years, are a loneliness for something you maybe can’t yet describe, and a palpable distance from whatever that thing might be,” says Brittany Nelson.

In her latest exhibition, “I can’t make you love me” at Chicago’s PATRON Gallery, the artist likens her youth as a queer kid in Montana to the experiences of Mars-roving robots and closeted writers from the annals of literary history. This investigation into the nuances of queer existence and post-war space exploration never strays too far off-planet, rooted firmly in Nelson’s upbringing—even as she questions the legitimacy of her own terrestrial nature.

From automated typewriters to single-channel videos of a haunting visit to the Hat Creek Observatory, the artist’s unconventional works delve into themes of otherness, solitude, and the enduring quest for community. Throughout the works on display, she illuminates a startling contrast between the vast cosmic expanse and intimate human emotion. To mark the show’s opening, Nelson dove into the significance of her material choices, the personal implications of her art, and the surprising unstaged moment that completed her video work.

CULTURED: How did science fiction become an interest for you?

Brittany Nelson: For me, art and science fiction are very similar; there is such an excitement at how avant-garde one can be in these worlds. In science fiction, you have an opportunity to think bigger, to be unconstrained by time, and to play out thought experiments. I’ve always loved the genre in cinema, but it was really my interest in James Tiptree Jr. (the pen name of Alice B. Sheldon) that got me into the literary world, and now I’m consuming as much as possible. She writes about worlds in which humans experiment with different forms of sexuality and embodiment, and where the boundaries of this planet either don’t apply or get stretched so thin they can no longer retain their original shape. I have a reverence in that she developed a framework for herself to escape the limitations of her life and the cultural era she was mired in. I often think of my time growing up and living in Montana, and I fantasize about a time machine that would allow me to go back and find the same freedom.

CULTURED: Where do you see the connection between the extraterrestrial and queer life?

Nelson: That is something I feel so deeply it is always hard to put into words, which is certainly why I try in many ways and from different angles to express it in the artwork. The more obvious answer is that it is about otherness, which is an experience we can all feel in some form or another and through a myriad of perspectives. At this point in the search for extraterrestrial life, we are finding nothing but silence. At the same time, queer life has been, and still is in ways large and small, rendered invisible.

Because of where and when I was born, these invisibilities have really formed my relationship to the world and how I move within it. The two dominant feelings that I have grappled with, especially in my formative years, are a loneliness for something you maybe can’t yet describe, and a palpable distance from whatever that thing might be. I feel a connection and fascination to the people and machines that are searching deep within the vacuum of the universe for a signal someone else is there. They are very proactively trying to close the gap and this soothes the feeling of impossibility I had as a young person to do this for myself.

CULTURED: What about analog technologies keeps you coming back to them?

Nelson: There are so many things I can say about my love affair with antiquated photographic processes. There is a level of manipulation by hand that is so tactile when making images; it allows my body to intervene into the material and leave a record of my touch. It is also a real collaboration with the volatility of the chemistry and how much control I can exert or choose to exert over it. I really thrive in an environment with endless variables to play with. There are so many photographic techniques, some historically important and others more obscure, that have their own unique visual language, but I am particularly interested in the processes that rely on light reacting to metals. To take something as fleeting as a small flash of light and inscribe it into silver, for me, is putting photography on the same grandiose scale as casting a sculpture in bronze.

CULTURED: How do you think this collection builds upon your existing body of work?

Nelson: A good friend of mine in the art world compared each body of work I create to adding one more line to a poem that is slowly being written over the years. This is really how I challenge myself to think about making work—with a long-term sensibility. None of the individual works or series are separate from each other, they are all meant to live in the same room together. In particular, the new video work “I can’t make you love me” feels like the most personal thing I’ve made, in part because I am performing (unseen) for the camera with a spotlight, but also because the video is an encapsulation of a series of six nights I spent alone out in the field with the 42 radio telescopes, built specifically for the SETI Institute. The institute was founded in 1984 and is a network of over 100 astronomers, astrophysicists and astrobiologists conducting research in the search for signals from extraterrestrial intelligence. This was a defining experience for me. During the day the telescopes would observe the sky, searching for signals of someone else out there. But at night, when the telescopes were pointed downward in their resting position, I would go out and search for them.

CULTURED: Where do you see the throughlines between the various series on view in this exhibition?

Nelson: Every work in this series is a different attempt to reach out and connect with someone or something else. I think these works also delight in their own failures to do so … The video work “I can’t make you love me” is maybe the most blatant work about the failure to connect. There is a particular scene in the video from a nearby lava tunnel. You see what appears to be disembodied spotlights emerge from around the corner and then a voice from behind the light asks me, “Are you a person?” This was entirely unscripted and a very fortuitous moment because this stranger did not say, “Is someone there?” He says specifically, “Are you a person?” I was honestly not sure what to answer at first. Yes, but I don’t feel like one.

CULTURED: Much of your work here appropriates other pieces or materials. What is your process like when reimagining source material to make it your own?

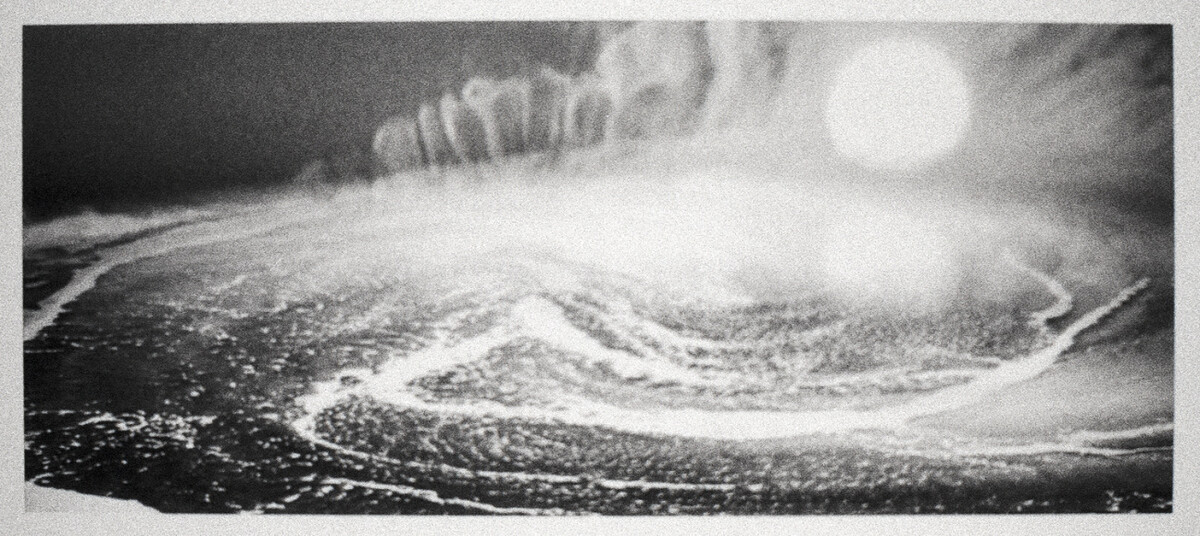

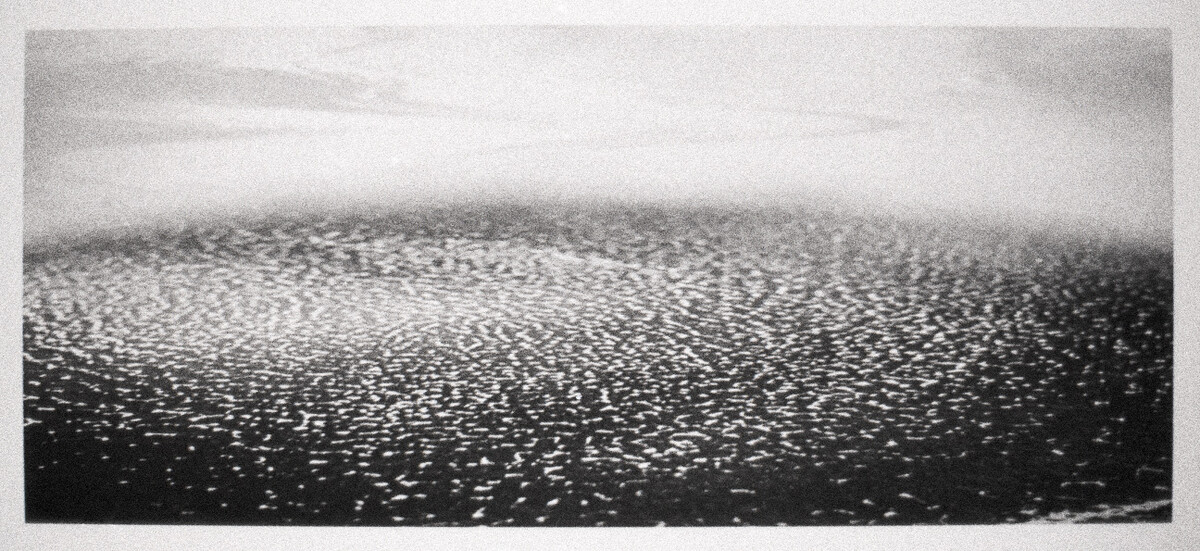

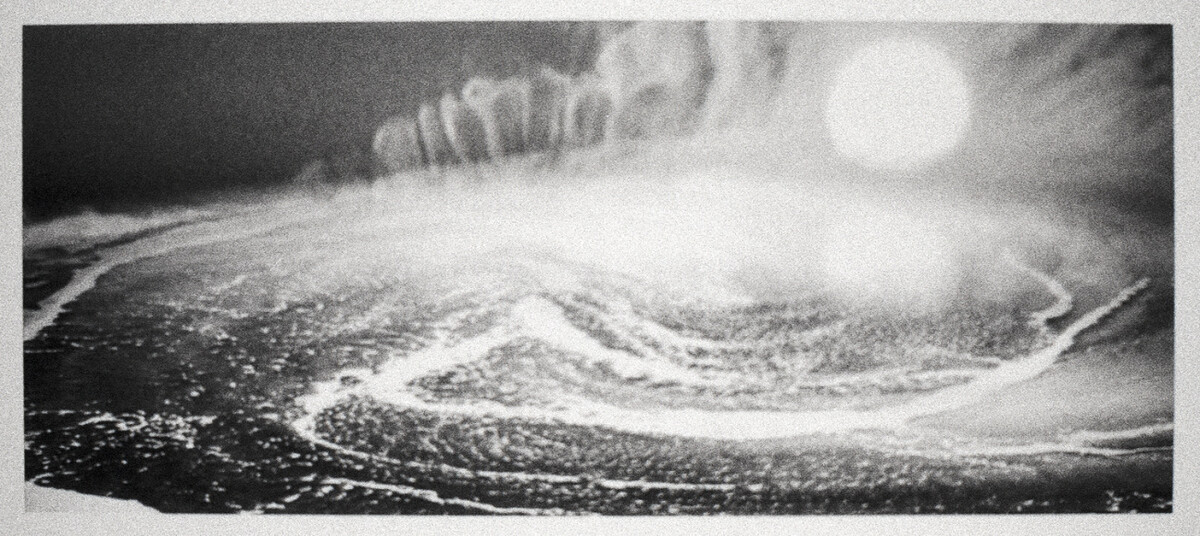

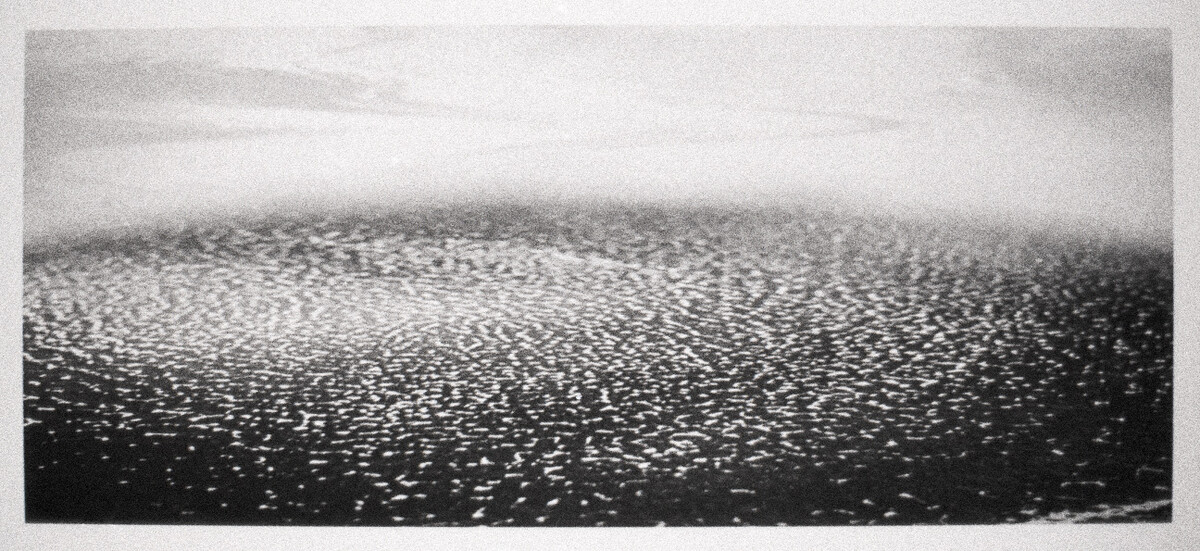

Nelson: Often, I am more interested in how images function in the world than in creating new ones. I want to take images that have already circulated and had an interesting life, and make you see them newly with all the connotation and baggage that I experience. For instance, with the work I had done previously with the Mars rover Opportunity image archive, I was seeing these landscapes of Mars being shared mostly on science and technology related websites and blogs, and there was an intense romanticism in these images that I feel needed to be acknowledged. This robot was only supposed to live ninety days and is instead wandering alone (her twin having died seven years previously) 14 years later and is taking images looking back at her own tracks through the landscape.

This landscape also looked very similar to my hometown in Montana, which was a very remote and gay-unfriendly city. These images from the rover were rife with loneliness and isolation for me, and it became my mission to encode those feelings back into them. I appropriated these landscapes and recreated them in as bromoil photographic prints, a pictorialist-era process from the 1920’s where the image is slowly remade by hand with lithographic ink and brushes. Most of the images created in the process were also landscapes. The marks of how they were made and handled exist everywhere in these images; they are suddenly now messy and alive.

All images courtesy of Brittany Nelson and PATRON Gallery.

“The two dominant feelings that I have grappled with, especially in my formative years, are a loneliness for something you maybe can’t yet describe, and a palpable distance from whatever that thing might be,” says Brittany Nelson.

In her latest exhibition, “I can’t make you love me” at Chicago’s PATRON Gallery, the artist likens her youth as a queer kid in Montana to the experiences of Mars-roving robots and closeted writers from the annals of literary history. This investigation into the nuances of queer existence and post-war space exploration never strays too far off-planet, rooted firmly in Nelson’s upbringing—even as she questions the legitimacy of her own terrestrial nature.

From automated typewriters to single-channel videos of a haunting visit to the Hat Creek Observatory, the artist’s unconventional works delve into themes of otherness, solitude, and the enduring quest for community. Throughout the works on display, she illuminates a startling contrast between the vast cosmic expanse and intimate human emotion. To mark the show’s opening, Nelson dove into the significance of her material choices, the personal implications of her art, and the surprising unstaged moment that completed her video work.

Brittany Nelson

CULTURED: How did science fiction become an interest for you?

Brittany Nelson: For me, art and science fiction are very similar; there is such an excitement at how avant-garde one can be in these worlds. In science fiction, you have an opportunity to think bigger, to be unconstrained by time, and to play out thought experiments. I’ve always loved the genre in cinema, but it was really my interest in James Tiptree Jr. (the pen name of Alice B. Sheldon) that got me into the literary world, and now I’m consuming as much as possible. She writes about worlds in which humans experiment with different forms of sexuality and embodiment, and where the boundaries of this planet either don’t apply or get stretched so thin they can no longer retain their original shape. I have a reverence in that she developed a framework for herself to escape the limitations of her life and the cultural era she was mired in. I often think of my time growing up and living in Montana, and I fantasize about a time machine that would allow me to go back and find the same freedom.

CULTURED: Where do you see the connection between the extraterrestrial and queer life?

Nelson: That is something I feel so deeply it is always hard to put into words, which is certainly why I try in many ways and from different angles to express it in the artwork. The more obvious answer is that it is about otherness, which is an experience we can all feel in some form or another and through a myriad of perspectives. At this point in the search for extraterrestrial life, we are finding nothing but silence. At the same time, queer life has been, and still is in ways large and small, rendered invisible.

Because of where and when I was born, these invisibilities have really formed my relationship to the world and how I move within it. The two dominant feelings that I have grappled with, especially in my formative years, are a loneliness for something you maybe can’t yet describe, and a palpable distance from whatever that thing might be. I feel a connection and fascination to the people and machines that are searching deep within the vacuum of the universe for a signal someone else is there. They are very proactively trying to close the gap and this soothes the feeling of impossibility I had as a young person to do this for myself.

CULTURED: What about analog technologies keeps you coming back to them?

Nelson: There are so many things I can say about my love affair with antiquated photographic processes. There is a level of manipulation by hand that is so tactile when making images; it allows my body to intervene into the material and leave a record of my touch. It is also a real collaboration with the volatility of the chemistry and how much control I can exert or choose to exert over it. I really thrive in an environment with endless variables to play with. There are so many photographic techniques, some historically important and others more obscure, that have their own unique visual language, but I am particularly interested in the processes that rely on light reacting to metals. To take something as fleeting as a small flash of light and inscribe it into silver, for me, is putting photography on the same grandiose scale as casting a sculpture in bronze.

CULTURED: How do you think this collection builds upon your existing body of work?

Nelson: A good friend of mine in the art world compared each body of work I create to adding one more line to a poem that is slowly being written over the years. This is really how I challenge myself to think about making work—with a long-term sensibility. None of the individual works or series are separate from each other, they are all meant to live in the same room together. In particular, the new video work “I can’t make you love me” feels like the most personal thing I’ve made, in part because I am performing (unseen) for the camera with a spotlight, but also because the video is an encapsulation of a series of six nights I spent alone out in the field with the 42 radio telescopes, built specifically for the SETI Institute. The institute was founded in 1984 and is a network of over 100 astronomers, astrophysicists and astrobiologists conducting research in the search for signals from extraterrestrial intelligence. This was a defining experience for me. During the day the telescopes would observe the sky, searching for signals of someone else out there. But at night, when the telescopes were pointed downward in their resting position, I would go out and search for them.

CULTURED: Where do you see the throughlines between the various series on view in this exhibition?

Nelson: Every work in this series is a different attempt to reach out and connect with someone or something else. I think these works also delight in their own failures to do so … The video work “I can’t make you love me” is maybe the most blatant work about the failure to connect. There is a particular scene in the video from a nearby lava tunnel. You see what appears to be disembodied spotlights emerge from around the corner and then a voice from behind the light asks me, “Are you a person?” This was entirely unscripted and a very fortuitous moment because this stranger did not say, “Is someone there?” He says specifically, “Are you a person?” I was honestly not sure what to answer at first. Yes, but I don’t feel like one.

CULTURED: Much of your work here appropriates other pieces or materials. What is your process like when reimagining source material to make it your own?

Nelson: Often, I am more interested in how images function in the world than in creating new ones. I want to take images that have already circulated and had an interesting life, and make you see them newly with all the connotation and baggage that I experience. For instance, with the work I had done previously with the Mars rover Opportunity image archive, I was seeing these landscapes of Mars being shared mostly on science and technology related websites and blogs, and there was an intense romanticism in these images that I feel needed to be acknowledged. This robot was only supposed to live ninety days and is instead wandering alone (her twin having died seven years previously) 14 years later and is taking images looking back at her own tracks through the landscape.

This landscape also looked very similar to my hometown in Montana, which was a very remote and gay-unfriendly city. These images from the rover were rife with loneliness and isolation for me, and it became my mission to encode those feelings back into them. I appropriated these landscapes and recreated them in as bromoil photographic prints, a pictorialist-era process from the 1920’s where the image is slowly remade by hand with lithographic ink and brushes. Most of the images created in the process were also landscapes. The marks of how they were made and handled exist everywhere in these images; they are suddenly now messy and alive.