A Blazing, Brilliant Whitney Biennial Heralds a New Kind of Body Art

ARTNews / Mar 13, 2024 / by Alex Greenberger / Go to Original

Paintings by Suzanne Jackson at the 2024 Whitney Biennial. Photo: Christopher Garcia Valle

If the Whitney Biennial really must reflect the United States as it stands right now, this year it had a particularly tall order.

The show had to deal with growing discontent surrounding war abroad, particularly in Gaza, and it also had to portray mounting anger at home, where conservative-led legislatures and the pandemic have threatened the lives of many Americans. And that’s not to mention that the country is at a crucial inflection point, with a presidential election coming in November.

But rather than taking up any of that, curators Chrissie Iles and Meg Onli have veered in a different direction. Their exhibition, which opens to the public on March 20, is light on loud, explicit political statements and heavy on conceptual art about bodies in flux. It’s the most challenging Whitney Biennial in several editions, and also the best since 2017.

Iles and Onli’s show, titled “Even Better Than the Real Thing,” marks a turn away from the opulence of the past couple Whitney Biennials, which privileged lush art, sometimes to a fault. A number of works here even revisit Minimalism, a movement that rejected visual pleasure in favor of flinty industrial forms arranged neatly into rows and grids.

Charisse Pearlina Weston is showing a sculpture formed from semi-translucent smoked glass sheets that tilt downward and hang above viewers’ heads. The sculpture, with a lengthy title that is just about as inscrutable as the object itself, contains a secret: its elements were borrowed from Weston’s 2022 show at the Queens Museum, where a bigger version of these glass plates obstructed the entryway to a gallery. Here, this new work—called un- (anterior ellipse[s] as mangled container; or where edges meet to wedge and [un]moor), and styled in that way, with irregular italicization and spacing—blocks a wall, much the same way Minimalists cut off parts of white cubes with their spare objects.

Charisse Pearlina Weston, un- (anterior ellipse[s] as mangled container; or where edges meet to wedge and [un]moor), 2024. Photo: Christopher Garcia Valle

The work finds an analog in Carolyn Lazard’s Toilette (2024), a group of ready-made medicine cabinets that encase Vaseline instead of drugs. Arranged on the floor back-to-back, these cabinets are evocative of Donald Judd’s steely stacks. Yet Lazard’s work, sleek as it may be, is anything but clinical—it suggests a human touch via the inclusion of lubricant. In these works, Weston and Lazard have literally given Minimalism a second life.

Carolyn Lazard, Toilette, 2024. Photo: Christopher Garcia Valle

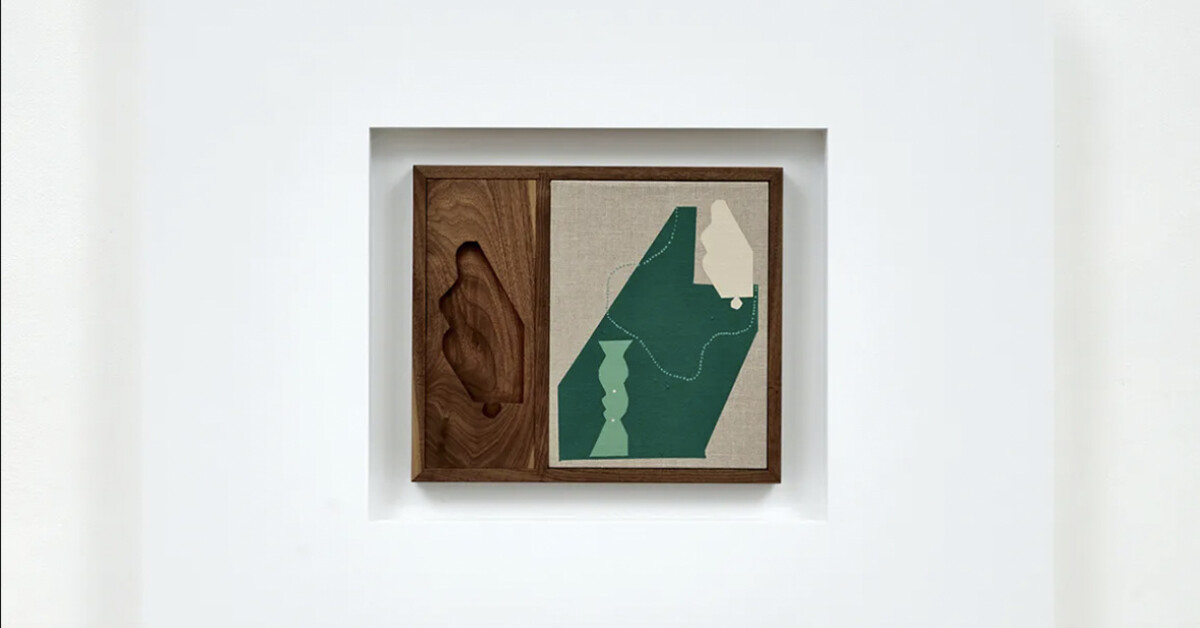

Many works in this biennial are clean, largely colorless, and slick. There are Jes Fan’s elegant sculptures, for which his spine, leg muscles, and innards were CAT scanned and 3D-printed, with the latter being embedded in the wall and barely visible; these abstracted parts are supplemented with oozy-looking glass elements draped across them. There are Harmony Hammond’s cryptic paintings, which are formed from reused fabrics that suggest bandages concealing mostly healed wounds. Peek around these white strips, and you may even spot a glimpse of blazing red paint.

Works by Harmony Hammond at the 2024 Whitney Biennial. Photo: Christopher Garcia Valle

Running through a central stairwell many visitors will use, there is Holland Andrews’s Air I Breathe: Radio (2024), a sound piece composed of echoing caws and booming hums. These sounds are sometimes transcendent and other times strange—Andrews made them by manipulating their voice using an effects processor. The sounds come from a series of speakers that hang in the middle of the staircase (a related work also plays in the museum’s publicly accessible freight elevator). Seen from above, those speakers look a bit like a spine’s vertebrae.

This Whitney Biennial seems to presage a new kind of body art, albeit one that is quite different from the strain seen in the 1960s and ’70s, when artists—particularly women artists—created their work using their arms, legs, and genitals. The goal back then was to show that an artist’s body cannot be divorced from their work. That now appears to be the objective once more. But now, those arms, legs, and genitals have dissolved entirely, fading away into architectural forms, fabrics, and everyday objects that merely resemble body parts. Perhaps this is all a response to the gradual paring back of bodily autonomy in this country—the unraveling of Roe v. Wade, a flotilla of anti-trans bills. Then again, these artworks are deliberately evasive, and their makers do not seem much interested in timeliness. Theirs is a kind of bodiless body art that channels alternate corporeal states without ever directly representing them.

Works by B. Ingrid Olson at the 2024 Whitney Biennial. Photo: Christopher Garcia Valle

It’s not that these artists have sought to vanquish the body from art-making—quite the opposite. Take one gorgeous sculpture from 2021 by Karyn Olivier composed of found buoys suspended above a tangle of multicolored ropes. The work’s title is How Many Ways Can You Disappear, the suggestion being that, while many bodies have fallen prey to the watery depths of the ocean, traces of their presences always linger behind. Bodies without bodies, frames without artworks, architecture without purpose: these all recur in a show of ironies and contradictions. The paradoxes are meant to be deliberately frustrating, nowhere more so than in Nikita Gale’s TEMPO RUBATO (STOLEN TIME), 2023–24, an installation that contains an unvarnished piano that plays on its own accord. Gale has rigged this instrument so that it cannot make any noise, however—the only audible music is the repeated clickety-clack of the keys moving against one another. Meanwhile, the lighting turns up and down dramatically, expectantly awaiting a musician who will never arrive. Works like TEMPO RUBATO decline to perform to the viewer’s liking. In doing so, they refuse their viewers’ gaze, mirroring an unwillingness by many artists here to participate in structures that seek to oppress them. It does not seem like a coincidence that Iles and Onli have loaded this Whitney Biennial with Black and trans artists.

Paintings by Mavis Pusey at the 2024 Whitney Biennial. . Photo: Christopher Garcia Valle

If there is a key to unlocking this mysterious, tough exhibition, it may be the paintings of Mavis Pusey, a Jamaican-born artist who spent a significant chunk of her career in Chelsea, not far from the Whitney. During the ’70s, Pusey, the only dead artist in the Whitney Biennial’s main section, painted shutters, boards, and window frames that smash against one another. While apertures are frequently represented, it is impossible to see through them—Pusey typically depicts what’s held within as a block of muted color. These works tempt viewers with the possibility that desolation may be revealed, only to deny viewers access to the world that Pusey envisions. There is, of course, an entire universe beyond the US that typically goes unrepresented in most Whitney Biennials. That is once again the case in this show, which contains no explicit references to Israel’s war in Gaza, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the crisis in the Congo, and the conflict in Sudan. With the exception of Demian DinéYazhi’s sculpture that includes the word “genocide” and a memorable Diane Severin Nguyen video about reenactments of the 1937 Nanjing Massacre, there’s not much about global strife at all. But it seems unfair to ding the show for that lacuna, since it feels like a conscious choice on the part of many of the show’s participants who were born abroad. Unlike some of the homegrown talents more inclined toward minimalism, these artists tend to represent traumas both past and present through decadence rather than disturbance.

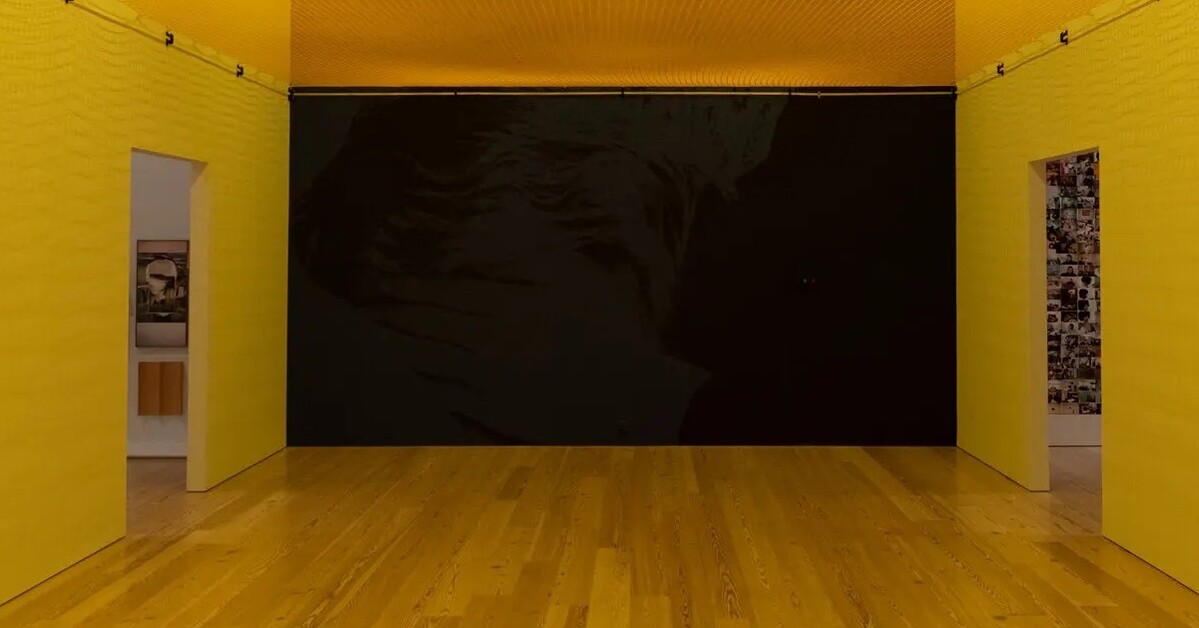

Maja Ruznic, The Past Awaiting the Future/Arrival of Drummers, 2023.©MAJA RUZNIC/PHOTO BRAD TRONE/COURTESY KARMA/COLLECTION OF THE ARTIST

Maja Ruznic, a New Mexico–based painter, recalls her time spent in an Austrian refugee camp after her family’s flight from war-torn Bosnia in Deep Calls to Deep (2023), a transcendent image of a solitary figure lost in a sea of green. Chilean artist Seba Calfuqueo channels her Mapuche heritage with TRAY TRAY KO (2022), a video in which she traipses around a verdant forest while dragging a long blue sheet of fabric; the iridescent garment seems to bend alongside a river and caress the dirt beneath, which Chilean loggers have sought to abuse for their own purposes. Santo Domingo–born choreographer Ligia Lewis revisits a 1521 revolt by enslaved people in the Dominican Republic in A Plot, A Scandal (2023), a video that culminates in the artist ecstatically dancing, crossing herself, sticking out her tongue, and flailing around in a moment of pure liberation.

Seba Calfuqueo, TRAY TRAY KO (still), 2022.©SEBA CALFUQUEO/PHOTO SEBASTIAN MELO/COURTESY THE ARTIST

In a handful of cases, the art here is itself freed from having to remain fixed and permanent. One of the few showstopping moments in a largely sedate exhibition comes courtesy of Suzanne Jackson, an octogenarian painter at the top of her game. She’s presenting a group of abstractions that are mounted to the ceiling and walls by hooks. Done using acrylic set within gel, a technique that she has called “acrylic on acrylic,” these paintings are speckled with refuse—trashed mesh, pistachio shells, shredded mail, and more. The works are like flayed skins that have been slathered in color; they will sag over the course of the show’s run, essentially aging in real time.

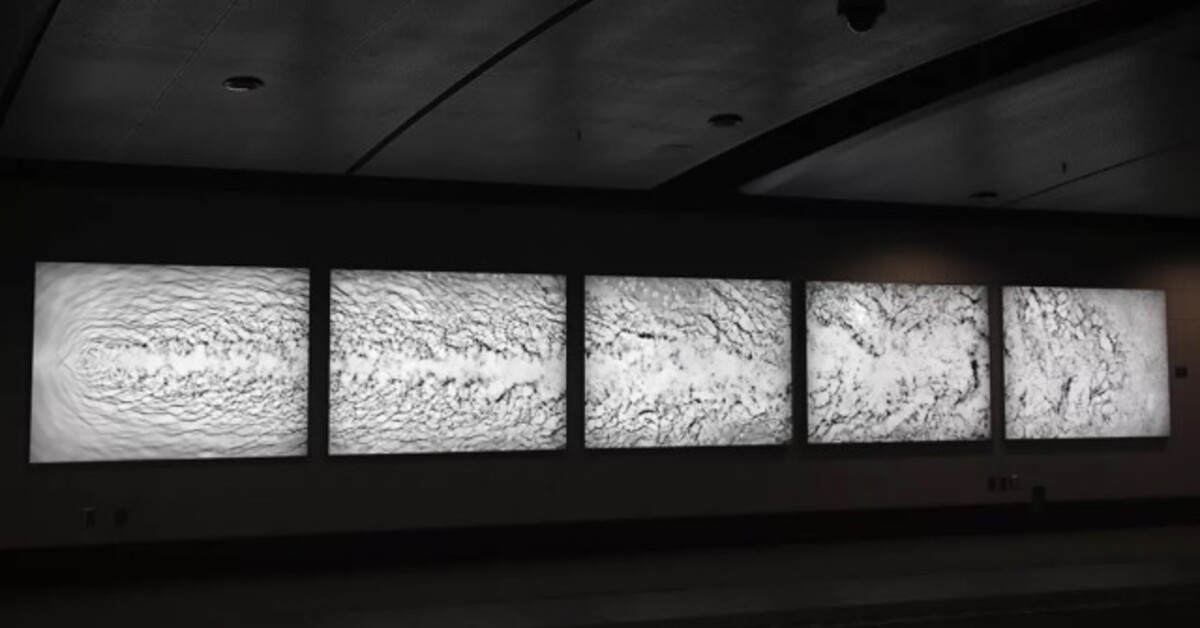

Certain works are intentionally unfinished. A wall has been set aside for a work by JJJJJerome Ellis, who will write a musical score that will be scrawled here as the show progresses. At press time, the wall was entirely blank. Meanwhile, an entire gallery has been awarded to works by Lotus L. Kang, who has unfurled large sheets of unfixed photographic film that will continue to develop as times goes on. Today, their surfaces are apricot-like shades of orange; next week, they may turn a very different hue; in a hundred years, perhaps they will be completely white. And, abutting a sun-splashed window, there is Eddie Rodolfo Aparicio’s Paloma Blanca Deja Volar / White Dove Let Us Fly (2024), an imposing hunk of amber that contains within it documents related to the activities of white activists in New York and Los Angeles, the artist’s hometown. As light continues to hit this work, the documents contained within will move about—heat will place pressure upon the texts explaining the white activists’ views, and so will critical eyes seeking to read these words. Meanwhile, the amber will transform, changing shape across the next few months. When I walked by, shards of the stuff had already hit the floor, where they were crunched beneath the feet of passersby.

Work by Lotus L. Kang at the 2024 Whitney Biennial. Photo: Christopher Gracia Valle.

Now for the big question: What’s any of this got to say about America? First, that American history is hardly set in stone—its contents are likely to shift as they are disturbed, as is the case with Aparicio’s sculpture. Second, that the core tenets of the nation’s culture—those recognizably American things such as the Founding Fathers and the Statue of Liberty—do not hold much relevancy for a generation that is mostly disinterested in them. This unpatriotic note is noisily sounded by Kiyan Williams’s sculpture Ruins of Empire II or The Earth Swallows the Master’s House (2024), an earthen depiction of the north section of the White House that appears to sink into an outdoor balcony. (An aluminum sculpture of the Black trans activist Marsha P. Johnson, also by Williams, gleefully looks on.) The Williams piece stands out in this sober show for its lack of subtlety and for its engagement with a distinctly American subject. Right now, it is one of the show’s rare misses, but as the work is exposed to the elements, it will likely transform into something much less obvious. I preferred the tattered, knotted American flag that appears in a Ser Serpas installation on the ground floor that is filled with garbage. The flag rests here on a disused piece of a sectional relegated to the corner—which is perhaps where the Stars and Stripes belongs during these depressing times. Nearby, there are barbells, a fire hydrant tipped on its side, half a broken mirror, and an exercise ball trapped in a tent armature.

Kiyan Williams, Ruins of Empire II or The Earth Swallows the Master’s House, 2024. Photo: Christopher Garcia Valle.

The Serpas installation, with all its tossed-off matter, looks a bit like the aftermath of a night of debauchery. In the context of this biennial, it also functions like an elegy for a celebratory moment post-lockdown when a state of normalcy had somewhat returned. It has finally come to an end. The party’s over, but it sure was fun while it lasted.