Samuel Levi Jones

4Columns / Jun 16, 2023 / by Aruna D’Souza / Go to Original

Samuel Levi Jones: Conscious Intuition, installation view. Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. Photo: Thomas Müller. Pictured, center foreground: Trojan Horse, 2023. Pulped encyclopedia pages and law-book covers, crate. Far left, on wall: Holding Space, 2023. Deconstructed and pulped law book, medical books, and bound-newspaper covers on canvas.

Samuel Levi Jones: Conscious Intuition, Galerie Lelong & Co., 528 West Twenty-Sixth Street, New York City, through June 17, 2023

• • •

Samuel Levi Jones’s 48 Portraits (Underexposed), made in 2012, while he was still working on his MFA at Mills College in Oakland, is the starting point for the artist’s latest show at Galerie Lelong. For the past decade or so, Jones has been thinking about books—encyclopedias, medical texts, law journals, bound volumes of newspapers—as well as other traces (such as flags) of larger political, cultural, and legal systems of authority and control. He tears these apart (or perhaps, more politely, deconstructs them) and refashions them into quilt-like canvases, rendering their original content mostly illegible.

Samuel Levi Jones, 48 Portraits (Underexposed), 2012. Suite of forty-eight inkjet prints on recycled Encyclopedia Britannica paper, each 24 1/2 × 22 inches. Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. © Samuel Levi Jones.

48 Portraits (Underexposed), Jones’s monochromatic gridded wall installation, is an origin point for much of what has come since, but it explicitly takes on another authoritative system: that of art history. In 1972, Gerhard Richter presented his own 48 Portraits in Germany’s pavilion at the Venice Biennale. The paintings were based on pictures culled from encyclopedias and dictionaries of (mostly dead) white men—scientists, writers, musicians, and other thinkers. On the surface, the installation reads as a pantheon of European cultural achievement. On closer inspection, however, it’s apparent that the figures were chosen largely, perhaps even primarily, not for their brilliance but for the directions their heads were turned in the source photographs—they all pivot toward a center point, as if their gazes had been orchestrated. For Richter, who like many of his peers was haunted by his elders’ complicity in the Holocaust, these intellectual forefathers were suspect; it’s not surprising that this pantheon looks more like a mausoleum.

Samuel Levi Jones, 48 Portraits (Underexposed), 2012 (detail, James Baldwin). Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. © Samuel Levi Jones.

Almost fifty years later, a friend gave Jones a set of the Encyclopedia Britannica—from 1972, no less. The artist had noticed that Richter’s piece excluded women (a fact long remarked upon) and people of color (a fact almost never mentioned). He began poring over the compendium’s pages to find out who else Richter could have included had he wanted to. The pickings were slim. So Jones decided to recreate Richter’s work, using photos of Black people (twenty-four men, twenty-four women) left out of the encyclopedia’s supposedly comprehensive scope, from Duke Ellington and W. E. B. Du Bois to Madam C. J. Walker and Mildred Loving. He darkened the portraits, making the installation appear, at first glance, like an array of black squares; it takes time to make out the faces. It’s a graceful conflation of medium and message: “They’re fighting for exposure,” Jones has said about these figures, too often erased from official histories. Contrary to Richter’s sepulchral gambit, Jones brings his subjects back to life.

Samuel Levi Jones: Conscious Intuition, installation view. Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. Photo: Thomas Müller. Pictured, right wall: Conscious Intuition, 2022–23. Pulped law-book covers, pulped US flag, and stars from US flag on canvas. Triptych, each 30 × 30 × 2 1/2 inches.

To underline the incompleteness of that 1972 Encyclopedia Britannica, Jones printed each face on paper made from its pulped pages. In the fourteen other works on view in Conscious Intuition, all from 2022 and 2023, Jones revisits his early gesture, using paper slurry to fashion paintings, sculptures, and even another installation. A triptych that shares the name of the exhibition is made by pulping law-book covers and a US flag; the flag’s fabric stars are laid into the work’s gloopy surfaces. Each panel consists of a black left half; a red, dirty white, or dark blue right half; and a stark white, Barnett Newman–esque “zip” running down the center—“who is afraid of red, white, and blue?” Jones seems to ask.

Samuel Levi Jones, Discerning Faculty, 2023. Deconstructed and pulped law books, medical books, bound-newspaper covers, and US flag on canvas, 40 × 70 inches. Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. © Samuel Levi Jones. Pervious Page.

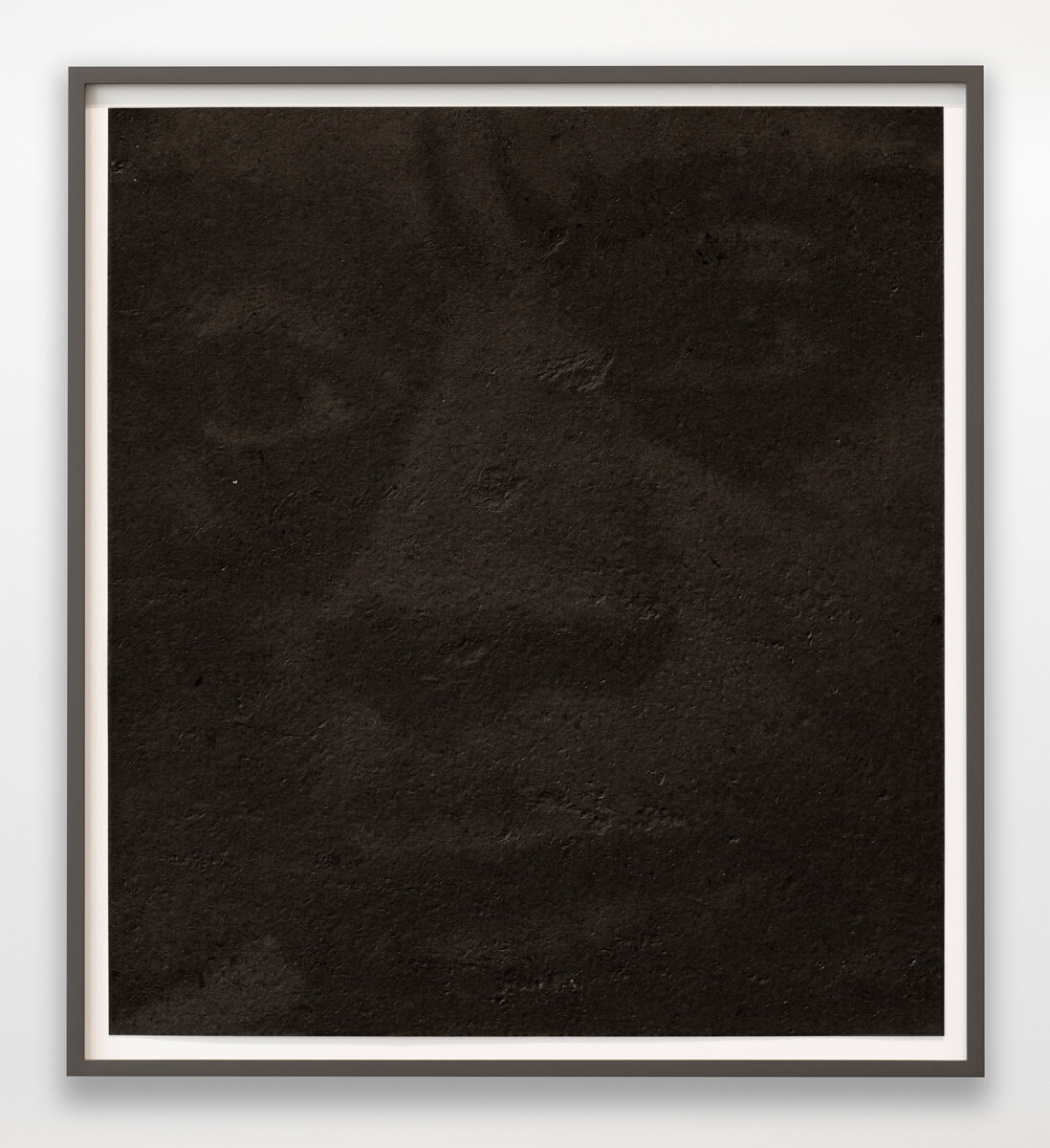

Many of the paintings in the show are framed so the edges are visible—look closely and you can see what’s underneath the stiff, scumbled top layer. In a talk at the gallery, Jones explained that he created these new works on top of his book-cover paintings, similar to the ones he’s been making for some years, constructed by sewing together torn-off jackets into a gridded, abstract composition. Holding Space and Discerning Faculty, two works hung near Conscious Intuition, allow that support to remain largely in view, the pulp being simply another rectangular element added to their colorful surfaces; in Pleasure from Pain and Dark Matter, the monochromatic, Ad Reinhardt–ian picture planes are occasionally punctuated by deconstructed book spines. By reusing these earlier book-jacket works as substrates, it’s as if Jones were taking aim at a new form of authority emerging from his own process, just like he takes aim at any other power structure.

Samuel Levi Jones: Conscious Intuition, installation view. Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. Photo: Thomas Müller. Pictured, left: Dark Matter, 2023. Deconstructed and pulped law-book covers on canvas. Right: Lost Truth, 2023. Pulped encyclopedia pages and pulped law-book covers, crate.

Two sculptures—Lost Truth and Trojan Horse—begin with wooden crates: Jones cast their interiors using pulped encyclopedia pages, applied a layer of pulped law-book covers to the resulting forms, and placed these objects on top of their new shipping crates. They stir up multiple associations: of how people were treated as cargo during the Middle Passage, and the (metaphorical) libraries full of knowledge that were lost in that act of human destruction; and of the monument, another vehicle for dominance and control. How not to see Trojan Horse as an abstracted equestrian sculpture—though its title evokes not eminence and prestige so much as a stealthy and malicious mechanism of annihilation? Here the monument becomes a symbol no less harmful than the partial histories offered in the tomes from which it was made. A sculptural installation, Library of Alexandria, consists of sparsely shelved volumes cast in this same recycled slurry. They are solid, unreadable, and even the paper they are constructed from is suspect for the information it ignores.

Samuel Levi Jones, The Library of Alexandria, 2023 (detail). Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. Photo: Thomas Müller. © Samuel Levi Jones.

The past two years have seen a rising tide of book-banning by right-wing politicians and activists across the country, as well as the rewriting of school textbooks to exclude histories pertaining to slavery and civil rights, sexual orientation, and gender, all in the name of “protecting children” (which children?) and “parental rights” (which parents?). In the face of this, Jones’s acts of destruction are, perhaps counterintuitively, cathartic. Forget the free-speech arguments and pearl-clutching at book-banning and burning: Jones’s work reminds us that the archive has always been ideologically suspect, has always been a mechanism of anti-Blackness and other forms of racism. Might as well puree the contents and make something better from the mush.

Aruna D’Souza is the 2022–23 W. W. Corcoran Professor of Social Engagement at the Corcoran School of Art and Design in Washington, DC and a contributor to the New York Times and 4Columns. She was awarded the Rabkin Prize for arts journalism in 2021.