Carmen Winant, Collier Schorr and More on Their Love For Chantal Akerman

AnOther Magazine / Oct 31, 2023 / by Kitty Grady / Go to Original

In 1976, at the age of 25, the late Belgian director Chantal Akerman created her masterpiece, Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles – a 201-minute epic about a housewife whose daily activities over three days are reproduced on film in hyperrealist duration. In it, Jeanne peels potatoes, tidies the house and turns tricks. Her routine, however, becomes a pressure cooker, waiting to bubble up and boil over.

Officially voted the ‘Greatest Film of All Time,’ in Sight & Sound’s decennial poll of critics and filmmakers earlier this year, Jeanne Dielman and Akerman finally got the mainstream recognition they deserved. Yet among so many feminist thinkers, artists, filmmakers and moviegoers, Akerman’s entire body of work – from her Chaplin-esque debut Saute Ma Ville to her Proust-inspired La Captive – has always occupied a place of veneration.

Her Voice: Echoes of Chantal Akerman, curated by Anne Ruygt at FOMU in Antwerp, is an exhibition of the director’s kissing cousins. Manon de Boer, Moyra Davey, Collier Schorr, Frida Orupabo, Carmen Winant, Gabby Laurent and Joanna Piotrowska, are seven contemporary artists whose photography and film work has been inspired by the Belgian filmmaker. The show – whose floor plan is designed after that of Jeanne Dielman’s apartment – features work that is far from homogenous: Frida Orupabo’s puppet-esque collages of women sit beside Carmen Winant’s ode to the American road trip she and her mother shared out of time; Collier Schorr’s two-channel Akerman Ballet, interprets Je, Tu, Il, Elle as a dance, while in the Hemlock Forest Moyra Davey’s obsession over the director’s death is more introverted. Meanwhile, Gaby Laurent and Joanna Piotrowska explore the body and domesticity. Opposite De Boer’s photo-sculpture Her Voice (which gives the show its name) is a bench where you can sit and listen to Akerman reading her story A Family in Brussels.

“I haven’t tried to find a compromise between myself and others. I have thought that the more particular I am, the more I address the general,” said Akerman. A Venn diagram of artists with Akerman at the prismatic centre, the exhibition proves the veracity of her words. Below, AnOther spoke to six of the artists – Collier Schorr, Frida Orupabo, Gabby Laurent, Manon de Boer, Moyra Davey and Carmen Winant – on the legacy and influence of the Belgian filmmaker.

“It was film stills from the bedroom scenes that lead me to Jeanne Dielman. The room is so aesthetically pleasing – the green walls, the heavy and dark wooden furniture, the mirror and cosmetics. And the stillness within each shot – the routines, the day-to-day activity – was so recognisable. Also, the portrayal of aloneness, trauma, and anger were felt strongly through Jeanne’s movements. At the time I was working as a social worker in an organisation for sex workers, and I felt Akerman’s portrayal of Jeanne was a strong and complex one, which didn’t reduce or objectify her. My contribution consists of collages from different shows and years. My work centres on Black life and Black experiences, especially Black womanhood: how we have been and still are portrayed, as well as finding ways to break with these narratives, which resonates with Akerman’s work.”

Collier Schorr

“I first saw Chantal Akerman’s film Je, Tu, Il, Elle in the early 1980s. It was the first time I saw two women having sex. It was the first time I saw a lesbian artist. I forgot about it until ten years ago when I started feeling the urge to perform with my subjects. Those impulses brought me back to Akerman, who was both a director and an object of her work. What I saw 40 years later, was that the film was a dance. That the movements were choreographed and blocked out: I was watching Judson Church mixed with Donald Judd and Robert Morris. I had always felt that female artists who inhabited their work were beautiful and female-presenting and that I was forever locked out of being able to exist as a spectacle. Akerman’s body, unlike an actress, was awkward and performative, vulnerable and powerful in its ordinariness.”

“As a Jew and a feminist, I’ve long connected with Akerman’s work. The thing that struck me about her films was the waiting. As women, we become stilled: waiting for periods, waiting for husbands to come home … In my thirties, I read Akerman’s book My Mother Laughs. I’m interested in how she described herself as a daughter until the day she died: ‘an old child’. It was as meaningful as being a mother. In my work, I combine frames from Super-8 films my mother made on a road trip when she was 18 with my own photographs from a similar trip. We start to merge, to see through each other’s eyes. I’m interested in the potential of intergenerational feminist exchange. That is what feels exciting about this exhibition. Akerman is gone, [but] her work, legacy and commitments remain. That is what makes feminism seem so vital and alive – the way we wrestle with what came before.”

Manon de Boer

“News From Home made a great impression on me. The main thing was her voice. I thought how different Akerman’s voice was to someone like Jean-Luc Godard’s. The male voice has much more authority, like it wants to teach you something, whereas Akerman’s is more vulnerable. That really struck me as something feminist, that the voice has a physical presence. When I was asked to create an image based on Akerman’s work, I decided to film the words ‘Her Voice’ on 16mm. But rather than project it as a film I created a sculpture of it as two circles, an eternal loop. Akerman never fears duration. I read she hates films where people say, “I forgot the time”. She said that’s awful that you could forget, because it is so important to be in time. That’s something that is important for me in my work – that you really experience time passing.”

Moyra Davey

“The first Akerman film I saw was Saute Ma Ville. I thought all the simple make-do devices were extraordinary: making sound effects with her voice. I got to know Babette Mangolte, Akerman’s cinematographer, whilst at UC San Diego. The shot on the 1 train in News From Home [which Davey recreates in Hemlock Forest] is a technical coup. The train is swaying all over the place and there’s this amazing depth of field, even though there’s not much light in a subway car. You’re not allowed to do that kind of thing without a permit, so it was a challenge to myself to see if I could get away with it. Eating marshmallows covered in powdered sugar [after Chantal’s sugar-eating scene in Je, Tu, Il, Elle] was a scene I enjoyed shooting so much. I got kind of high eating it, allowing myself this crazy indulgence.”

Gabby Laurent

“Jeanne Dielman is all about a woman doing something over and over again. But I think of this repetition or ritual as a way to escape pain. It’s how I view my project on falling. By falling again and again, I mask my pain – it’s about accepting loss and dealing with grief. For me, Jeanne’s daily acts also mask pain. There’s a point where they fall apart, and that’s where her fury emerges. There’s a lot of pain in News from Home, too. It’s very simple – using street scenes of New York and reading letters from her mother – but the two things together are very powerful. When the sound of the narrator is drowned out by the sound of traffic, that, for me, might be the most succinct thing an artist has ever done. It’s exactly how I feel when I’m talking with the people closest to me. It’s not even miscommunication. It’s just like you’re not hearing each other anymore.”

Her Voice: Echoes of Chantal Akerman is on show at FOMU in Antwerp until 10 March 2024.

Officially voted the ‘Greatest Film of All Time,’ in Sight & Sound’s decennial poll of critics and filmmakers earlier this year, Jeanne Dielman and Akerman finally got the mainstream recognition they deserved. Yet among so many feminist thinkers, artists, filmmakers and moviegoers, Akerman’s entire body of work – from her Chaplin-esque debut Saute Ma Ville to her Proust-inspired La Captive – has always occupied a place of veneration.

Her Voice: Echoes of Chantal Akerman, curated by Anne Ruygt at FOMU in Antwerp, is an exhibition of the director’s kissing cousins. Manon de Boer, Moyra Davey, Collier Schorr, Frida Orupabo, Carmen Winant, Gabby Laurent and Joanna Piotrowska, are seven contemporary artists whose photography and film work has been inspired by the Belgian filmmaker. The show – whose floor plan is designed after that of Jeanne Dielman’s apartment – features work that is far from homogenous: Frida Orupabo’s puppet-esque collages of women sit beside Carmen Winant’s ode to the American road trip she and her mother shared out of time; Collier Schorr’s two-channel Akerman Ballet, interprets Je, Tu, Il, Elle as a dance, while in the Hemlock Forest Moyra Davey’s obsession over the director’s death is more introverted. Meanwhile, Gaby Laurent and Joanna Piotrowska explore the body and domesticity. Opposite De Boer’s photo-sculpture Her Voice (which gives the show its name) is a bench where you can sit and listen to Akerman reading her story A Family in Brussels.

“I haven’t tried to find a compromise between myself and others. I have thought that the more particular I am, the more I address the general,” said Akerman. A Venn diagram of artists with Akerman at the prismatic centre, the exhibition proves the veracity of her words. Below, AnOther spoke to six of the artists – Collier Schorr, Frida Orupabo, Gabby Laurent, Manon de Boer, Moyra Davey and Carmen Winant – on the legacy and influence of the Belgian filmmaker.

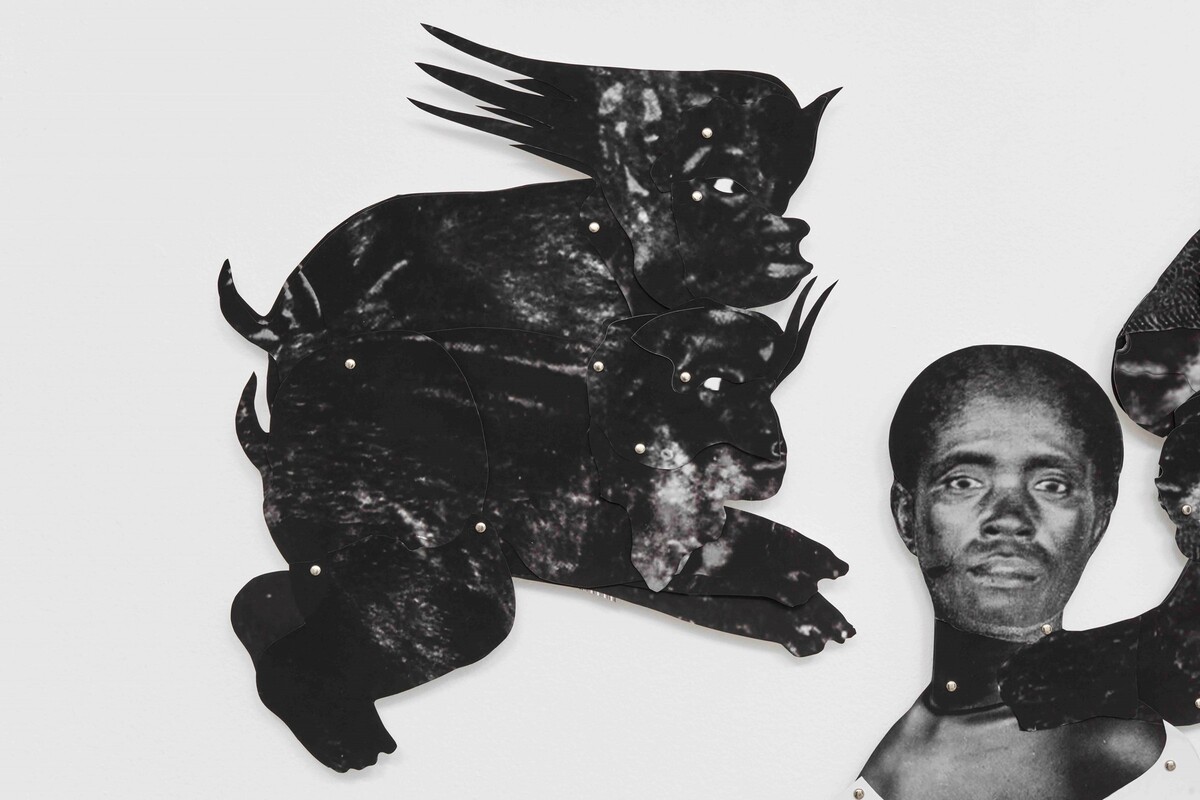

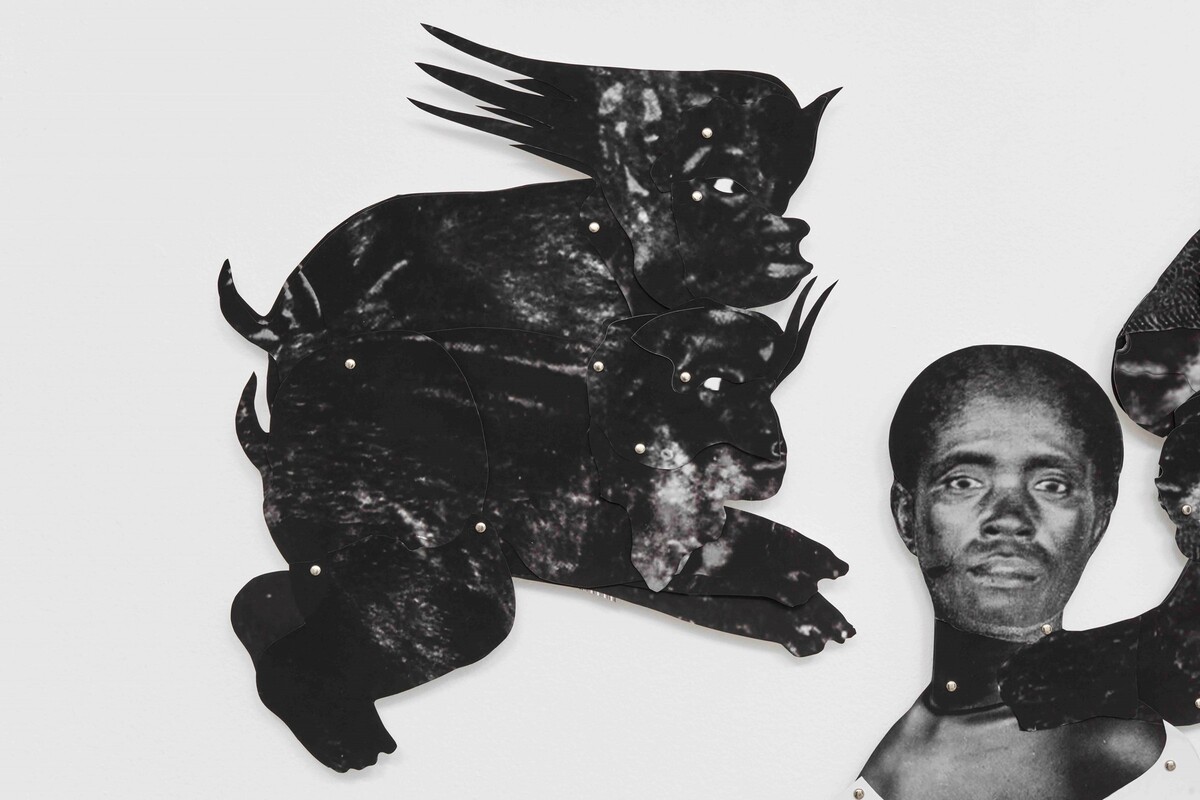

Frida Orupabo, Untitled, 2019© Frida Orupabo. Courtesy The Artist and Galerie Nordenhake Berlin/Stockholm/Mexico City. Photo: Carl Henrik Tillberg

“It was film stills from the bedroom scenes that lead me to Jeanne Dielman. The room is so aesthetically pleasing – the green walls, the heavy and dark wooden furniture, the mirror and cosmetics. And the stillness within each shot – the routines, the day-to-day activity – was so recognisable. Also, the portrayal of aloneness, trauma, and anger were felt strongly through Jeanne’s movements. At the time I was working as a social worker in an organisation for sex workers, and I felt Akerman’s portrayal of Jeanne was a strong and complex one, which didn’t reduce or objectify her. My contribution consists of collages from different shows and years. My work centres on Black life and Black experiences, especially Black womanhood: how we have been and still are portrayed, as well as finding ways to break with these narratives, which resonates with Akerman’s work.”

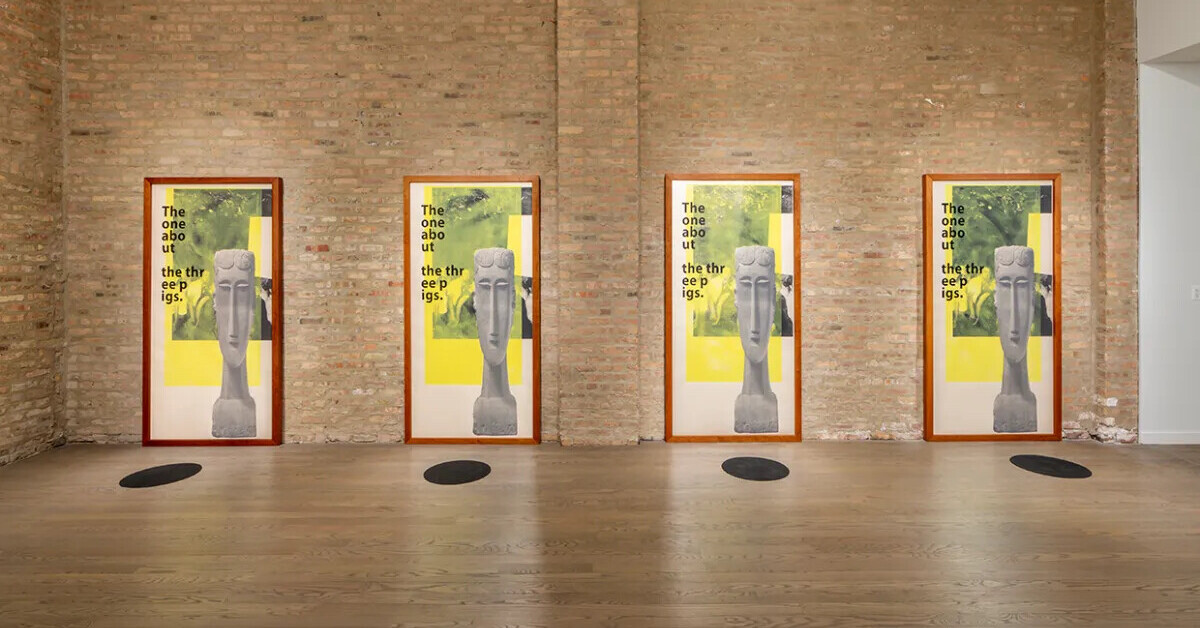

Collier Schorr

“I first saw Chantal Akerman’s film Je, Tu, Il, Elle in the early 1980s. It was the first time I saw two women having sex. It was the first time I saw a lesbian artist. I forgot about it until ten years ago when I started feeling the urge to perform with my subjects. Those impulses brought me back to Akerman, who was both a director and an object of her work. What I saw 40 years later, was that the film was a dance. That the movements were choreographed and blocked out: I was watching Judson Church mixed with Donald Judd and Robert Morris. I had always felt that female artists who inhabited their work were beautiful and female-presenting and that I was forever locked out of being able to exist as a spectacle. Akerman’s body, unlike an actress, was awkward and performative, vulnerable and powerful in its ordinariness.”

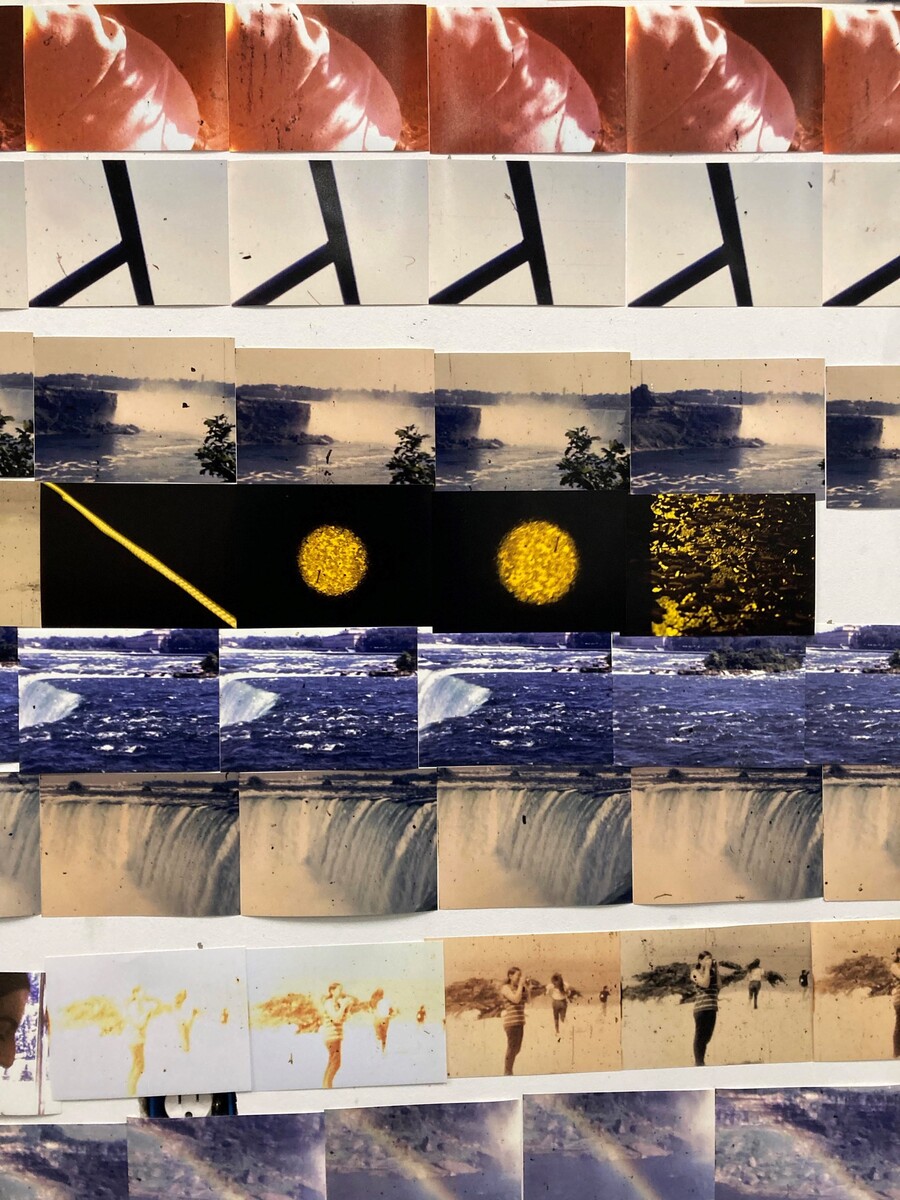

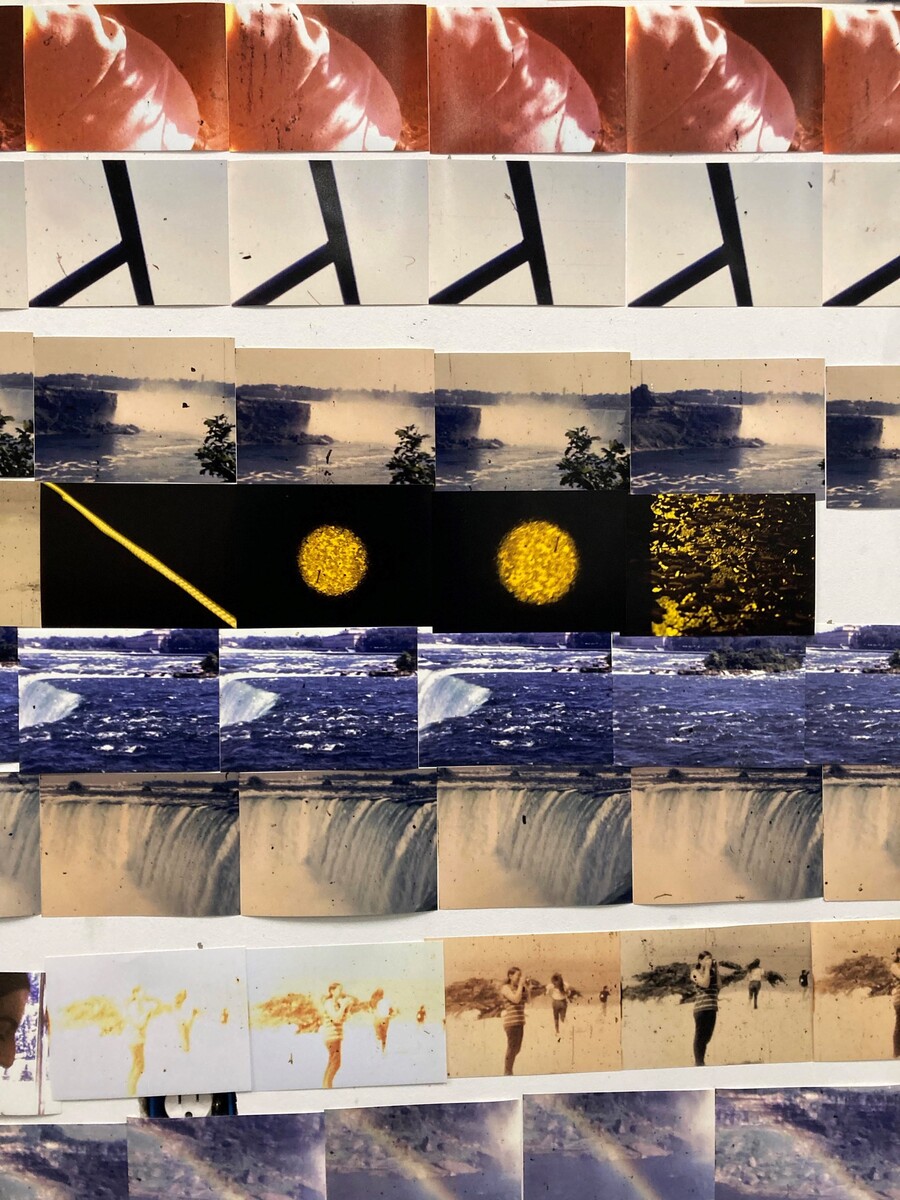

My Mother and Eye (detail), 2023© Carmen Winant

“As a Jew and a feminist, I’ve long connected with Akerman’s work. The thing that struck me about her films was the waiting. As women, we become stilled: waiting for periods, waiting for husbands to come home … In my thirties, I read Akerman’s book My Mother Laughs. I’m interested in how she described herself as a daughter until the day she died: ‘an old child’. It was as meaningful as being a mother. In my work, I combine frames from Super-8 films my mother made on a road trip when she was 18 with my own photographs from a similar trip. We start to merge, to see through each other’s eyes. I’m interested in the potential of intergenerational feminist exchange. That is what feels exciting about this exhibition. Akerman is gone, [but] her work, legacy and commitments remain. That is what makes feminism seem so vital and alive – the way we wrestle with what came before.”

Manon de Boer

“News From Home made a great impression on me. The main thing was her voice. I thought how different Akerman’s voice was to someone like Jean-Luc Godard’s. The male voice has much more authority, like it wants to teach you something, whereas Akerman’s is more vulnerable. That really struck me as something feminist, that the voice has a physical presence. When I was asked to create an image based on Akerman’s work, I decided to film the words ‘Her Voice’ on 16mm. But rather than project it as a film I created a sculpture of it as two circles, an eternal loop. Akerman never fears duration. I read she hates films where people say, “I forgot the time”. She said that’s awful that you could forget, because it is so important to be in time. That’s something that is important for me in my work – that you really experience time passing.”

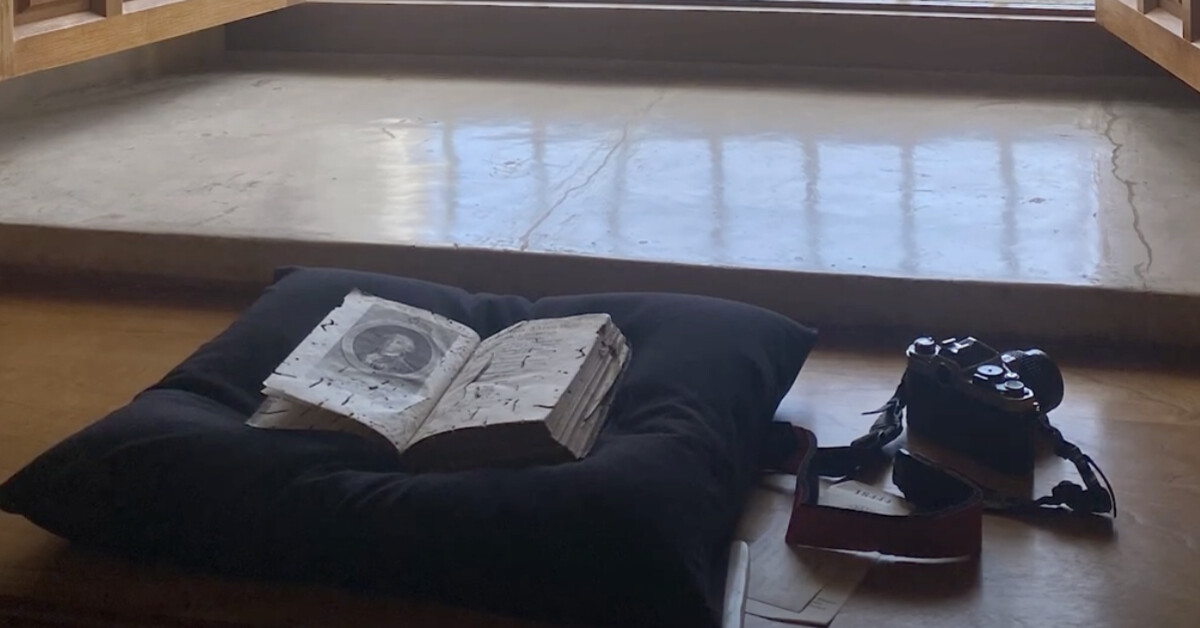

Moyra Davey, Hemlock Forest, 2016 (video)© Moyra Davey, Courtesy greengrassi, London; and Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne/New York

Moyra Davey

“The first Akerman film I saw was Saute Ma Ville. I thought all the simple make-do devices were extraordinary: making sound effects with her voice. I got to know Babette Mangolte, Akerman’s cinematographer, whilst at UC San Diego. The shot on the 1 train in News From Home [which Davey recreates in Hemlock Forest] is a technical coup. The train is swaying all over the place and there’s this amazing depth of field, even though there’s not much light in a subway car. You’re not allowed to do that kind of thing without a permit, so it was a challenge to myself to see if I could get away with it. Eating marshmallows covered in powdered sugar [after Chantal’s sugar-eating scene in Je, Tu, Il, Elle] was a scene I enjoyed shooting so much. I got kind of high eating it, allowing myself this crazy indulgence.”

Gabby Laurent

“Jeanne Dielman is all about a woman doing something over and over again. But I think of this repetition or ritual as a way to escape pain. It’s how I view my project on falling. By falling again and again, I mask my pain – it’s about accepting loss and dealing with grief. For me, Jeanne’s daily acts also mask pain. There’s a point where they fall apart, and that’s where her fury emerges. There’s a lot of pain in News from Home, too. It’s very simple – using street scenes of New York and reading letters from her mother – but the two things together are very powerful. When the sound of the narrator is drowned out by the sound of traffic, that, for me, might be the most succinct thing an artist has ever done. It’s exactly how I feel when I’m talking with the people closest to me. It’s not even miscommunication. It’s just like you’re not hearing each other anymore.”

Her Voice: Echoes of Chantal Akerman is on show at FOMU in Antwerp until 10 March 2024.