DePaul Art Museum reckons with dearth of Latinx artists in U.S. collections

Chicago Tribune / Jun 25, 2021 / by Lori Waxman / Go to Original

Before viewing LatinXAmerican, a vigorous and timely exhibition of 40-plus artists of Latinx heritage that fills the entire DePaul Art Museum, you must first pass a 12-foot-tall green plumed headdress. Installed in the museum’s front windows, the transparent image depicts a 500-year-old relic, many times enlarged, that is said to have belonged to the Aztec ruler Moctezuma II, who gifted it to a Spanish conquistador. It currently belongs to the Museum of Ethnology in Vienna, Austria, where it is the subject of repatriation claims by the Mexican government. Meanwhile a replica sits in the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City.

To create this towering picture — through which, depending on the light and your position, can be glimpsed the El train, Fullerton Avenue and the museum interior — artist Claudia Peña Salinas blended photographs of the original and its copy. Neatly encapsulating ideas of authority, patrimony, authenticity and hybridity, “Quetzalli,” named for the bird that provided its 500 feathers, is the perfect entryway to LatinXAmerican.

And yet, “Quetzalli” is technically a stand-alone project and not part of the exhibition proper. But then LatinXAmerican is not

a classic show of its kind, focused on the identity of a marginalized group as understood through its art. It does not provide thematic groupings of artworks nor biographical information on the included artists. It in no way essentializes what it means to be a person of Latinx descent who lives in the United States.

Instead the exhibition, which is part of DPAM’s multi-year Latinx Initiative, is concerned with examining and ultimately righting structural wrongs, the kind perpetrated by major American museums, whose collections, according to a 2018 survey, contain just 2.8% of work by artists of Latinx heritage, despite the fact that Latinx people make up 18.5% of the U.S. population. LatinXAmerican is basically a collections show, drawn from the holdings of DPAM, but one that takes a critical look at what isn’t there as much as what is, temporarily plugging those holes with works made by some of the most exciting artists of today, many of them Chicagoans.

What’s here, then, is what you get with any truly robust group show: good to great art, by makers familiar and not, in a surprising variety of media and styles, hung in ways that stimulate connection-making without being burdensome.

The main gallery opens with Ester Hernandez’s print of a skeleton girl in a huipil and ICE cuff, a biting riff on the Sun-Maid raisins box. Maybe the “Sun Raid” girl gets you thinking about portraiture, about how value is ascribed through the figures of generals, martyrs, society ladies and, yes, even fictional farm maidens. Want to think about grocery stores and their shelves full of political, social and cultural consequence? Look left, to Alberto Aguilar’s trio of hand-lettered signs, the kind typically found in the windows of Mexican food shops, but here featuring words that playfully challenge assumptions about cultural difference rather than advertise the price of chicken parts.

Look right, to José Lerma’s suite of four portrait paintings, copies of canvases that hang in the Art Institute of Chicago, rendered in the standard construction materials of silicone applied to burlap stretched over standard doors. Those portraits hang atop a wallpaper sketched by Lerma as a teeming mass of hundreds of unidentifiable people. Maybe now consider the invisibility of immigrant labor and its tortured relationship to land politics? Look back to the left, where hangs a cotton tapestry, striated brown from being rubbed against the rusty corrugated metal border fence that has run along the San Diego-Tijuana border since 1994, in the area where Tanya Aguiñiga grew up. That’s a kind of wallpaper, too.

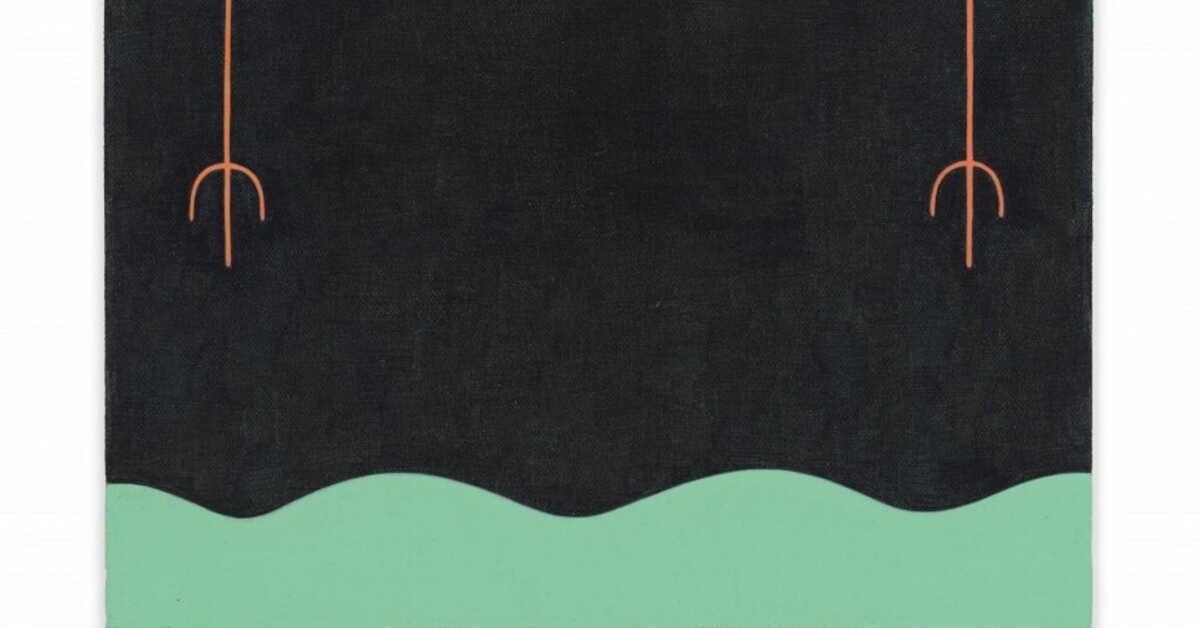

The front gallery offers a sequence of artists whose work depends on the potent relationship of words to color, sound, shape and form. Caroline Kent pairs brief typewritten texts — startling descriptions of a man drinking coffee, a woman who turned into a snake — with blotches of pastel and black paint, creating combinations whose poignancy belies their randomness. In an ongoing series, Dianna Frid embroiders phrases into paper so densely covered with graphite it appears to be a molten metal out of which the letters arise. On view is a volatile set, based on the newspaper obituaries of two men, one an anti- Castro dissident, the other a close ally of the Cuban leader; interpretation of the chosen quotes and even the color of their thread will depend on your personal politics.

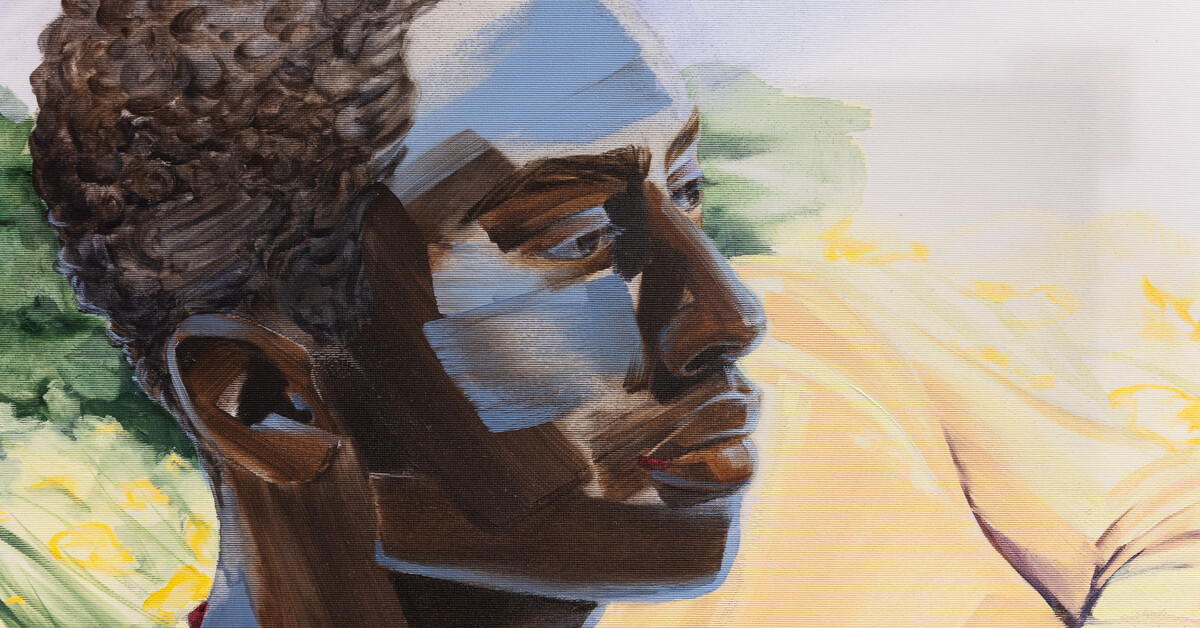

Upstairs is a chapel-like room, centered around Salvador Jiménez-Flores’s fantastical totem pole, an 8-foot-tall ceramic cactus sprouting spikes, masked luchadors, bricks and shimmering sunglasses, topped by the eagle and serpent of the Mexican flag. Arrayed around it are saints of all sorts: Sam Kirk’s radiant stained-glass portrait of a blue-haloed woman with skin in every shade of brown; Vincent Valdez’s Native American boxer, badly beat up, pierced by arrows, but, like Saint Sebastian, still standing; and Rodrigo Lara’s diminutive memorials of plastic grass, little marble tiles, and porcelain figures expertly modeled but pierced by hollows and gashes that reveal process and pain.

The exhibit goes on, upstairs and down, with Alejandro Jiménez-Flores’s impossibly delicate plaster reliefs, encasing flower petals and dirt, and Edra Soto’s elegant MDF screen, based on Puerto Rican porch architecture and displaying green liquor bottles, scrubbed clean after being found on her daily neighborhood walks. There’s a photograph of Maria Gaspar lying on the ground in the Marin Headlands of Northern California, nearly undetectable in her custom suit of dry grasses, and Nicole Marroquin’s posters commemorating events, activists and institutions central to the history of Chicago’s Latinx community.

More than half of the artworks in LatinXAmerican are part of the museum’s collection, with about a dozen having been acquired in the past two years alone. The rest are on loan from the artists, but with any luck, and a lot of institutional (and donor) commitment, the next time they are on display, their labels will say, “Collection of DePaul Art Museum.”