Caroline Kent ‘Writing’ Visually at Hawthorn Contemporary

Shepherd / Mar 10, 2020 / by Shane McAdams / Go to Original

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE GALLERY

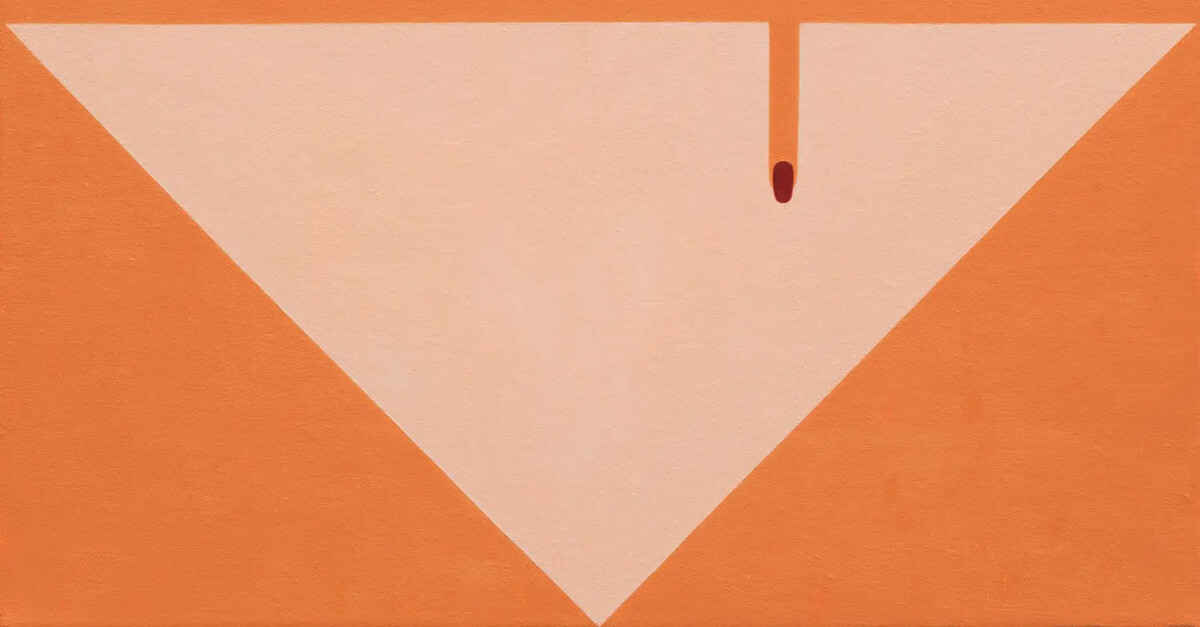

Caroline Kent’s large rectilinear wall painting completed in tonal orange struck me quickly as one of those rare colors that has few immediate associations. I might have disregarded my stray observation if other ambiguities hadn’t subsequently presented themselves. The painting itself mimics a large work on canvas for a moment before being recognized as a carefully taped off shape with slightly skewed angles and a conspicuously removed notch on the lower left. Two sculptural quotation marks slyly bracket the entire painting, and when they’re noticed, the whole piece—indeed the show itself, aptly titled “Writing Forms”— moves unmistakably from the realm of visual forms to that of language.

As a child, I aspired to possess Crayola crayon sets with the greatest number of colors. I wanted 64 with a sharpener but was forced to make do with 16. I dreamed of the unicorns that lived in boxes of 128, thinking there were colors from other dimensions. I became a grown-up the day I realized that every new color was simply a shade or tint of those in my paltry sets of 16. Still, the names given to those colors, those interstitial hues in-between the others—cornsilk, carnation, thistle—carved out new sensory pathways in my mind, nearly equivalent to those unseen wavelengths of light might have. This is of course is a testament to the power of language rather than color theory.

This meditation gripped me as I took in Kent’s abstract painterly quotation and confirmed how cleverly she smuggled my own associations with color over the border into the dimension of language. Withholding symbolic handles—fire- engine red, or banana yellow, or sky blue—or any tangible content, she managed to make that pictorial quotation about universal color and form; a quote about abstraction and not of it, even while it looked like it.

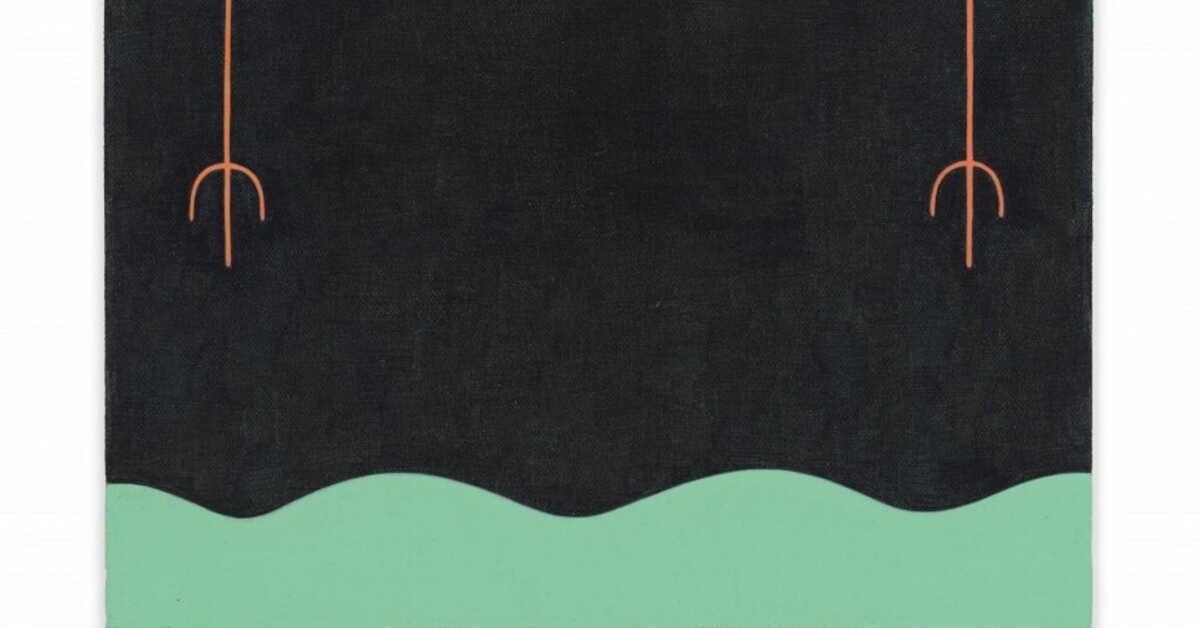

On the wall opposite the large wall piece, four smaller abstract paintings in dull flesh tones on black backgrounds complicate the ongoing semiotic inquiry. As she did with color, Kent addresses concrete subject matter with a similarly willful desire to force ambiguity. The black forms in these paintings feel caught in-between crude figuration and formal abstraction, living in an altered version of a colorless color. Each painting is framed by a theatrical hood that encourages a representational and performative read. But all these quasi- corporeal forms live in a figure/ground holding pattern as signifiers of content rather than representations of it.

A tapered painted plinth at the back of the gallery eludes easy identification. Eight feet high, drab orange again, with a pink cutout grate at the top, it insists on being identified as a nameable symbol that never quite arrives. Lingering in textual mode after the earlier parentheses, I struggled and failed to eventually place the sculpture’s symbolic derivation. I left the show a little puzzled, still wondering if the sculpture was meant to be read or simply seen. After a day or two of stewing, I concluded that the answer was probably “both.”

That particular sculptural element, like the other work in the greater installation, represent forced collisions between languages: of art and writing, of abstraction and text. Seeing any language in its most orthodox function, we tend to normalize it, forgetting its biases and modalities. Kent urges us to stay awake and resist the sensational possibilities of her media. Marshall McLuhan said, more than five decades ago, that “the medium is the message,” and his statement is as true as ever at Hawthorn Contemporary through April 18.