Photography’s Past and Present at the Getty Center

The Wall Street Journal / May 29, 2024 / by William Meyers / Go to Original

The exhibition ‘Hippolyte Bayard: A Persistent Pioneer’ examines one of the lesser-known originators of the medium, while ‘Nineteenth-Century Photography Now’ tracks the continuing influence of its early practitioners and techniques.

How many people understand the technology their cellphones use to produce a photographic

image? Almost none. “Hippolyte Bayard: A Persistent Pioneer” and “Nineteenth-Century

Photography Now,” two exhibitions at the Getty Center through July 7, take us back to the

beginnings of photography when those who made pictures experimented constantly with the

materials and chemicals they used. In 1839, Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre announced his

process for fixing a positive image on a metal plate, the daguerreotype: He was awarded a

pension by the French government. In England, that same year, William Henry Fox Talbot

announced to great acclaim his process for fixing a negative image on paper; the negative could

then be used to make many positives. The two are frequently cited as the founders of

photography, but Hippolyte Bayard (1801-1887), who also in 1839 demonstrated his process for

fixing a positive image on paper, is mostly forgotten. The Getty Center has the largest collection

of Bayard’s prints outside of France, and Carolyn Peter, assistant curator of photographs, has

organized an exhibition to raise awareness of his achievements.

Bayard was a bureaucrat, with a day job at the Ministry of Finance, and lacked the political

connections that boosted Daguerre’s reputation and the wealth that aided Talbot. But over the

years he made constant improvements in several processes, took admirable photographs, and was

appreciated by his contemporaries. The gallery the exhibition is housed in is painted a dark

Tuscan green because the prints must be protected from excessive light, and because many of the

pictures were taken in Bayard’s green-leafed suburban garden. In the center of the room is a

vitrine in which sits “Dessins photographiques sur Papier: Recueil No. 2” (“Photographic

Drawings on Paper: Collection No. 2”), the album from which the Getty obtained 145 of

Bayard’s experiments with different processes on paper. Microfade testing that measures

sensitivity to light determined which prints were stable enough to be exhibited; others are shown

in facsimile, and the entire album can be viewed digitally.

Because of the very long exposure time a direct positive print required, the subjects of two

examples (shown in facsimiles) are statues, “Still Life with Statuettes” and “Bather by É.-M.

Falconet, Bust and Medallion” (both 1839). The spectral “Lace Glove” (1843-46) is a

Cyanotype, a process invented by John Herschel that Bayard sometimes used. He took cityscapes

in parts of Paris near his office, such as “View of Rooftops and the Vendôme Column” (about

1846) and “Place de la Concorde” (c. July 6, 1848), both salted paper prints, and also of sites

close to his home in Breteuil; “Windmills of Montmartre” (1842), another salted paper print, is

an example.

Bayard participated in successful commercial portrait studios, and he was the first photographer

to create an extensive series of self-portraits. A handsome, intelligent-looking, and appealing

man, he sat still for the long exposure time needed for “Self-Portrait” (1845-49) and stood, but

leaned on a barrel, for “Self-Portrait” (1847); both are salted paper prints (although the first is a

facsimile), and both were taken in the bright sunlight of his garden. In “Hippolyte Bayard and the

Invention of Photography,” the catalog edited by Karen Hellman and Ms. Peter, there are more

self-portraits, including “Self-Portrait With the Legion of Honor” (c. 1863-69); he stands proudly

wearing the rosette awarded him after the French government in 1863 finally recognized his

scientific and artistic contributions.

Ms. Hellman, a former associate curator, inspired by her work with the Bayard materials,

conceived “Nineteenth-Century Photography Now” as a way to access the influence that early

photographers still have. The exhibition includes work from the past by 23 named and three

anonymous photographers plus an additional 16 included in an album; there are 21 present-day

artists. It is organized around five themes: Identity, Time, Spirit, Landscape and Circulation. The

picture that serves as an introduction to the show is “Untitled ‘point de vue’” (1827) by Joseph

Nicéphore Niépce, a faded heliograph on pewter, that Daido Moriyama keeps a reproduction in

his studio; the wall text quotes him saying, “it serves as a gentle daily reminder to be mindful of

the origins and essence of photography.” There are two photographs by Mr. Moriyama prompted

by Niépce’s bit of primitive technology.

The Identity section has a lovely portrait by Julia Margaret Cameron of her grand-niece,

“Florence After the Manner of the Old Masters” (1872), and a circular print 33 3/16 inches in

diameter by Carrie Mae Weems of four reclining children, “After Manet,” from the series “May

Days Long Forgotten” (2003); both are modeled on classical paintings. It also has “Affaire

Alaux, Faubourg St. Honoré – L’Assassin” (Nov. 2, 1902), a print by Alphonse Bertillon, the

inventor of the mug shot, showing the mustached villain full-face and in profile; it is

accompanied by over 20 pictures of sites that played a significant role in Bertillon’s life taken in

2012 by Stéphanie Solinas employing a “crime scene” approach.

The ghosts, demons and transmogrifying creatures that are features of Japanese Noh plays and

movies seem to animate the 13 pictures Lieko Shiga took in London in 2005. She said, “When I

saw a series of spirit photographs from the nineteenth century, I felt a strange sense of familiarity

and sympathy.” Ms. Shiga’s images are in the Spirit section, as is “Seated Woman With ‘Spirit’

of a Young Man” taken by an unknown American tintypist about 1865-75. Spirit photographs

include faint images of departed loved ones and are, of course, fakes.

Mark Ruwedel’s statement in a wall text notes that “The legacy of nineteenth-century

expeditionary photography was most important to me when working on my Westward series.” He

cites Timothy O’Sullivan, Alexander Gardner and A.J. Russell. The Landscape section has a

print by A.J. Russell, “Embankment No. 3 West of Granite Cannon. [Wyoming]” (April 1868),

and seven pictures by Mr. Ruwedel: “Union Pacific #39 (After A.J. Russell)” and “Union Pacific

#67 (After A.J. Russell)” (1994 and 1996, respectively) and five others with no specific

acknowledgments but clearly influenced by his 19th-century mentors.

Some contemporary photographers adopt not only their predecessors’ subject matter, but their

outdated technologies as well, exploiting the unique qualities these technologies possess. Andrea

Chung is represented in the Circulation section by four cyanotypes she took in 2016. Khadija

Saye has nine hand-printed silkscreen prints from original tintypes dated 2019 to 2020 in the

Spirit section. There are three ambrotypes from 2017 by Laura Larson and seven decidedly

archaic looking ones by Myra Greene from 2017-2018, all in the Identity section.

It is going on two centuries since successful methods of fixing an image were first discovered,

and photographic technology has now been brought by continuous development to your

cellphone, but serious artists still look to those who went before for inspiration and for ideas on

how to co-opt the past

‘Portrait in the Garden’ (c. 1847), by Hippolyte Bayard. Photo: Getty Museum

How many people understand the technology their cellphones use to produce a photographic

image? Almost none. “Hippolyte Bayard: A Persistent Pioneer” and “Nineteenth-Century

Photography Now,” two exhibitions at the Getty Center through July 7, take us back to the

beginnings of photography when those who made pictures experimented constantly with the

materials and chemicals they used. In 1839, Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre announced his

process for fixing a positive image on a metal plate, the daguerreotype: He was awarded a

pension by the French government. In England, that same year, William Henry Fox Talbot

announced to great acclaim his process for fixing a negative image on paper; the negative could

then be used to make many positives. The two are frequently cited as the founders of

photography, but Hippolyte Bayard (1801-1887), who also in 1839 demonstrated his process for

fixing a positive image on paper, is mostly forgotten. The Getty Center has the largest collection

of Bayard’s prints outside of France, and Carolyn Peter, assistant curator of photographs, has

organized an exhibition to raise awareness of his achievements.

Bayard was a bureaucrat, with a day job at the Ministry of Finance, and lacked the political

connections that boosted Daguerre’s reputation and the wealth that aided Talbot. But over the

years he made constant improvements in several processes, took admirable photographs, and was

appreciated by his contemporaries. The gallery the exhibition is housed in is painted a dark

Tuscan green because the prints must be protected from excessive light, and because many of the

pictures were taken in Bayard’s green-leafed suburban garden. In the center of the room is a

vitrine in which sits “Dessins photographiques sur Papier: Recueil No. 2” (“Photographic

Drawings on Paper: Collection No. 2”), the album from which the Getty obtained 145 of

Bayard’s experiments with different processes on paper. Microfade testing that measures

sensitivity to light determined which prints were stable enough to be exhibited; others are shown

in facsimile, and the entire album can be viewed digitally.

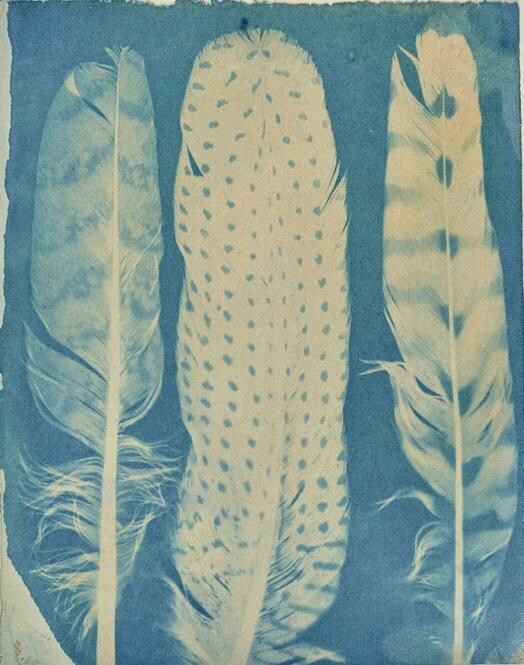

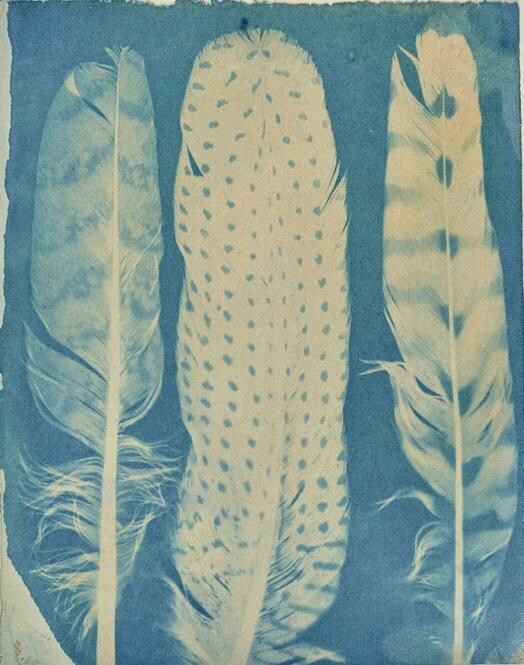

‘Three Feathers’ (c. 1842-43), by Bayard Photo: Getty Museum

Because of the very long exposure time a direct positive print required, the subjects of two

examples (shown in facsimiles) are statues, “Still Life with Statuettes” and “Bather by É.-M.

Falconet, Bust and Medallion” (both 1839). The spectral “Lace Glove” (1843-46) is a

Cyanotype, a process invented by John Herschel that Bayard sometimes used. He took cityscapes

in parts of Paris near his office, such as “View of Rooftops and the Vendôme Column” (about

1846) and “Place de la Concorde” (c. July 6, 1848), both salted paper prints, and also of sites

close to his home in Breteuil; “Windmills of Montmartre” (1842), another salted paper print, is

an example.

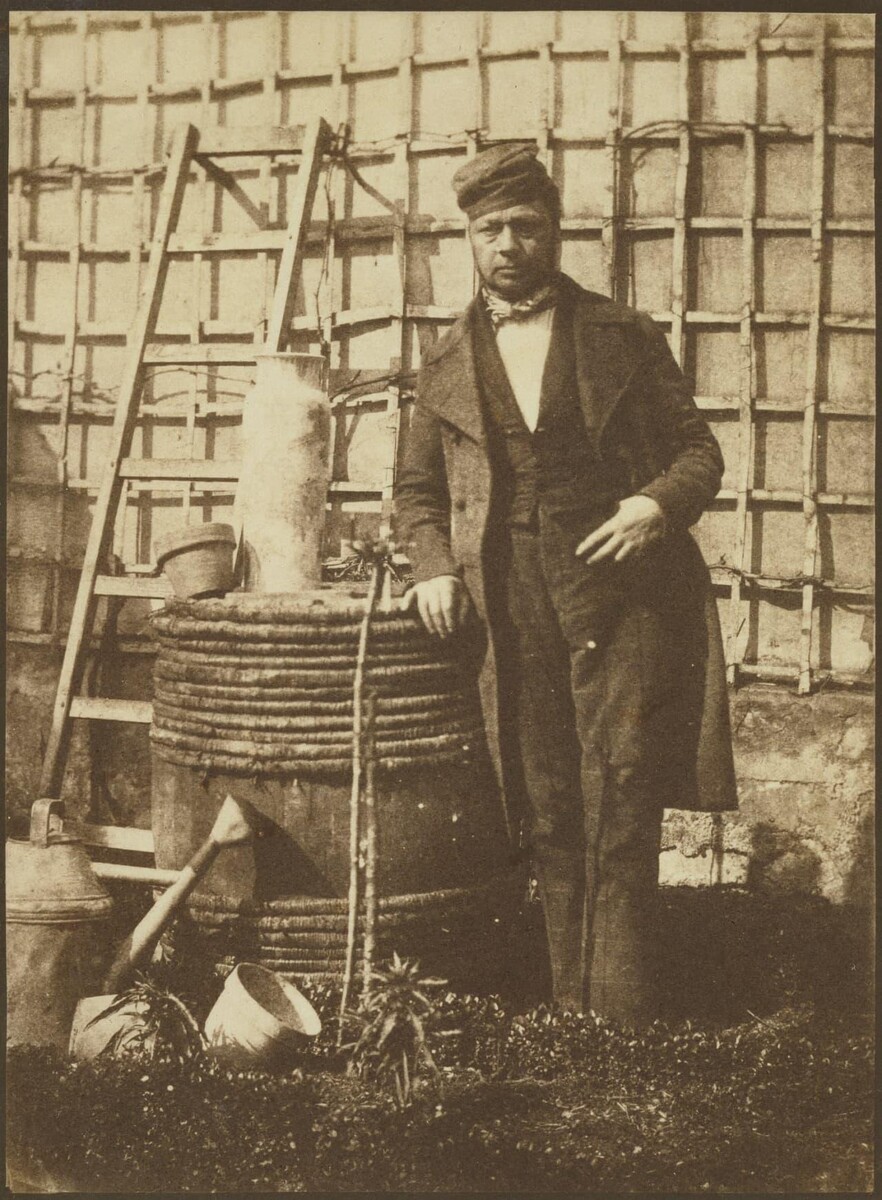

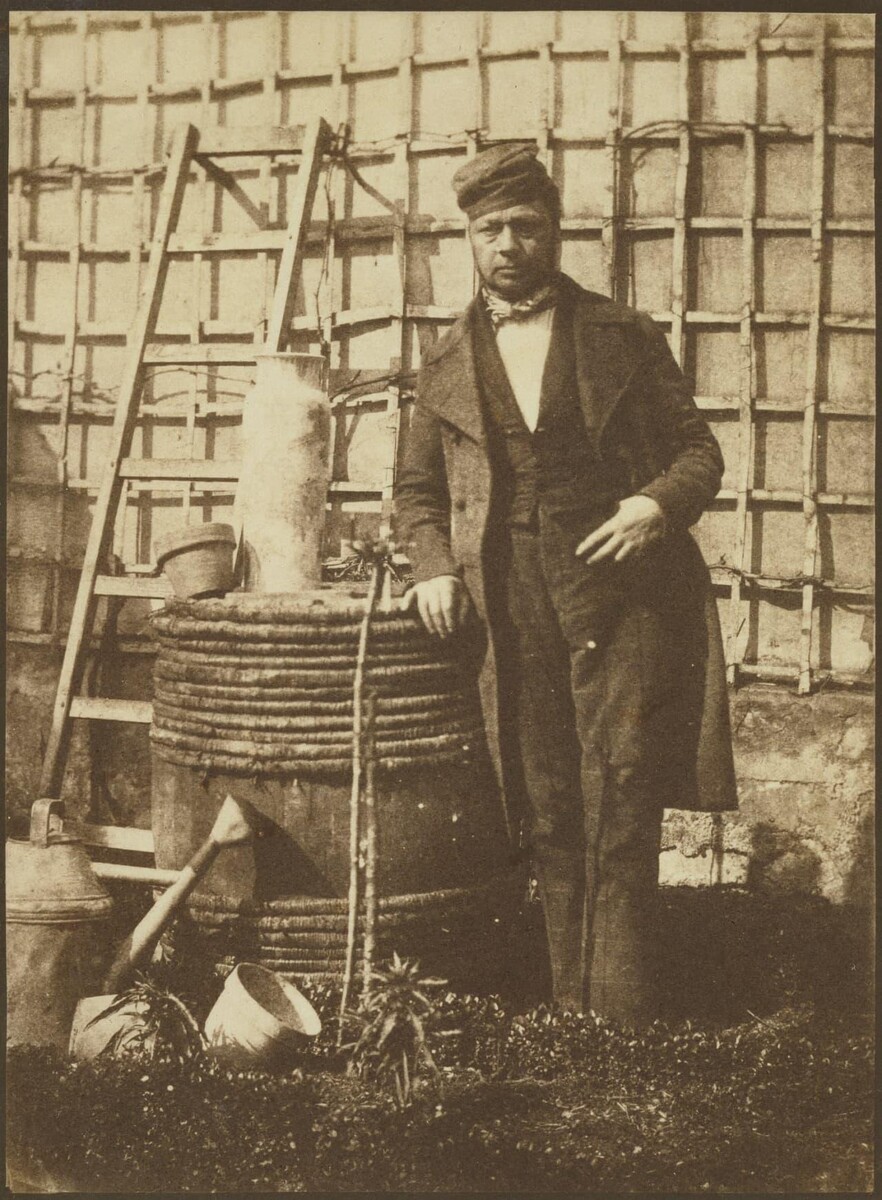

Bayard’s ‘Self-Portrait’ (1847). Photo: Getty Museum

Bayard participated in successful commercial portrait studios, and he was the first photographer

to create an extensive series of self-portraits. A handsome, intelligent-looking, and appealing

man, he sat still for the long exposure time needed for “Self-Portrait” (1845-49) and stood, but

leaned on a barrel, for “Self-Portrait” (1847); both are salted paper prints (although the first is a

facsimile), and both were taken in the bright sunlight of his garden. In “Hippolyte Bayard and the

Invention of Photography,” the catalog edited by Karen Hellman and Ms. Peter, there are more

self-portraits, including “Self-Portrait With the Legion of Honor” (c. 1863-69); he stands proudly

wearing the rosette awarded him after the French government in 1863 finally recognized his

scientific and artistic contributions.

Ms. Hellman, a former associate curator, inspired by her work with the Bayard materials,

conceived “Nineteenth-Century Photography Now” as a way to access the influence that early

photographers still have. The exhibition includes work from the past by 23 named and three

anonymous photographers plus an additional 16 included in an album; there are 21 present-day

artists. It is organized around five themes: Identity, Time, Spirit, Landscape and Circulation. The

picture that serves as an introduction to the show is “Untitled ‘point de vue’” (1827) by Joseph

Nicéphore Niépce, a faded heliograph on pewter, that Daido Moriyama keeps a reproduction in

his studio; the wall text quotes him saying, “it serves as a gentle daily reminder to be mindful of

the origins and essence of photography.” There are two photographs by Mr. Moriyama prompted

by Niépce’s bit of primitive technology.

The Identity section has a lovely portrait by Julia Margaret Cameron of her grand-niece,

“Florence After the Manner of the Old Masters” (1872), and a circular print 33 3/16 inches in

diameter by Carrie Mae Weems of four reclining children, “After Manet,” from the series “May

Days Long Forgotten” (2003); both are modeled on classical paintings. It also has “Affaire

Alaux, Faubourg St. Honoré – L’Assassin” (Nov. 2, 1902), a print by Alphonse Bertillon, the

inventor of the mug shot, showing the mustached villain full-face and in profile; it is

accompanied by over 20 pictures of sites that played a significant role in Bertillon’s life taken in

2012 by Stéphanie Solinas employing a “crime scene” approach.

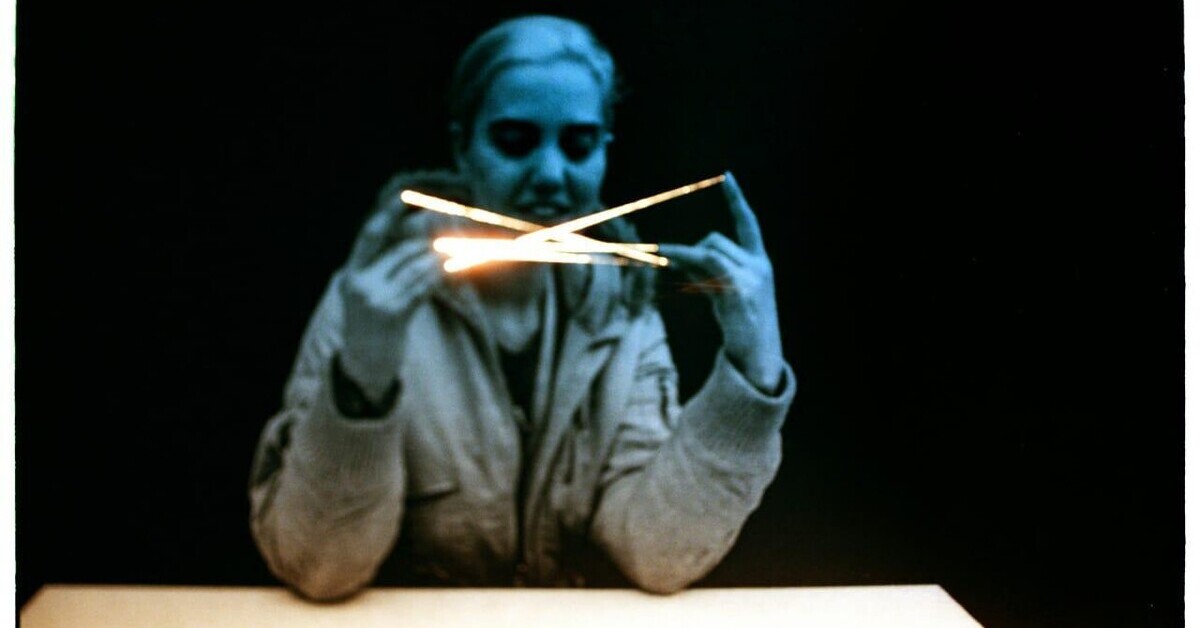

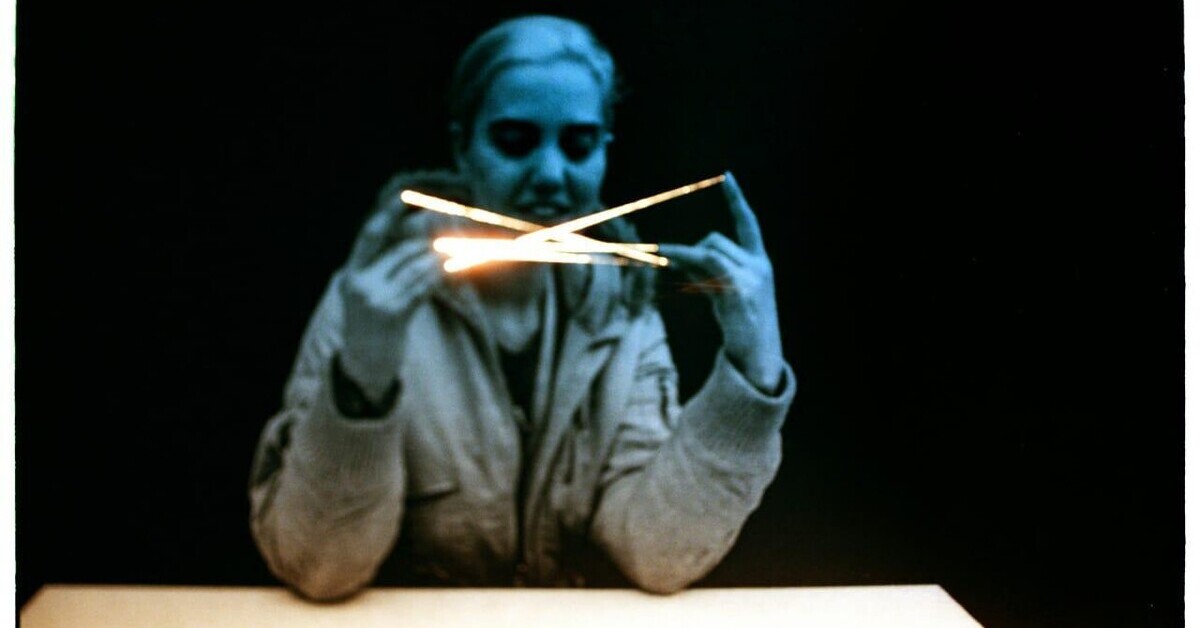

‘Talking with Me’ (2005) by Lieko Shiga. Photo: Getty Museum

The ghosts, demons and transmogrifying creatures that are features of Japanese Noh plays and

movies seem to animate the 13 pictures Lieko Shiga took in London in 2005. She said, “When I

saw a series of spirit photographs from the nineteenth century, I felt a strange sense of familiarity

and sympathy.” Ms. Shiga’s images are in the Spirit section, as is “Seated Woman With ‘Spirit’

of a Young Man” taken by an unknown American tintypist about 1865-75. Spirit photographs

include faint images of departed loved ones and are, of course, fakes.

Mark Ruwedel’s statement in a wall text notes that “The legacy of nineteenth-century

expeditionary photography was most important to me when working on my Westward series.” He

cites Timothy O’Sullivan, Alexander Gardner and A.J. Russell. The Landscape section has a

print by A.J. Russell, “Embankment No. 3 West of Granite Cannon. [Wyoming]” (April 1868),

and seven pictures by Mr. Ruwedel: “Union Pacific #39 (After A.J. Russell)” and “Union Pacific

#67 (After A.J. Russell)” (1994 and 1996, respectively) and five others with no specific

acknowledgments but clearly influenced by his 19th-century mentors.

Some contemporary photographers adopt not only their predecessors’ subject matter, but their

outdated technologies as well, exploiting the unique qualities these technologies possess. Andrea

Chung is represented in the Circulation section by four cyanotypes she took in 2016. Khadija

Saye has nine hand-printed silkscreen prints from original tintypes dated 2019 to 2020 in the

Spirit section. There are three ambrotypes from 2017 by Laura Larson and seven decidedly

archaic looking ones by Myra Greene from 2017-2018, all in the Identity section.

It is going on two centuries since successful methods of fixing an image were first discovered,

and photographic technology has now been brought by continuous development to your

cellphone, but serious artists still look to those who went before for inspiration and for ideas on

how to co-opt the past