Interview: Charisse Pearlina Weston by Zoë Hopkins

BOMB / Jul 29, 2024 / by Zoë Hopkins / Go to Original

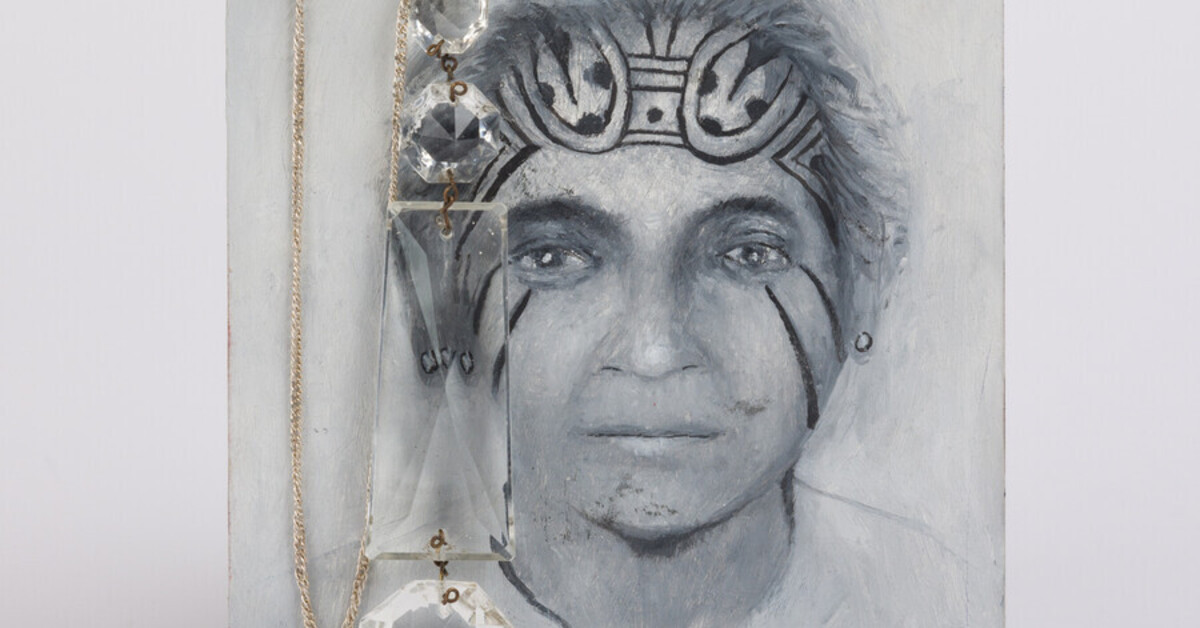

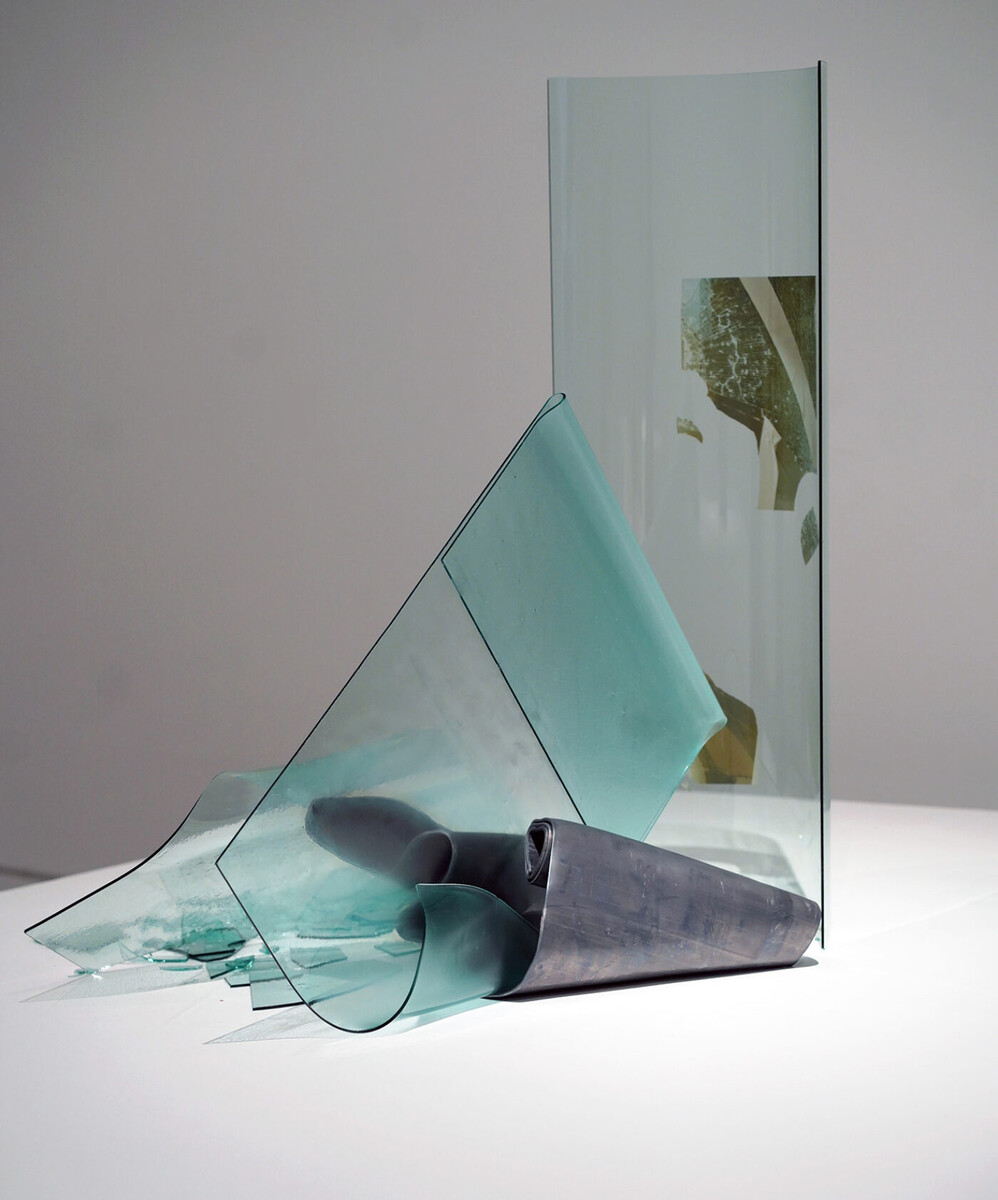

Charisse Pearlina Weston, to lift the flesh of its flesh, the bone of its bone (Brockton Trial Court, June 3, 2020); after collapse, 2022, slumped and enfolded glass, photographic decal, etched text, lead. Photo by Charisse Pearlina Weston. Courtesy of the artist.

One must move carefully around Charisse Pearlina Weston’s work. Made of glass, concrete, and lead, her sculptures require a certain caution and engender an uncomfortable awareness of their instability. For Weston, the fragility of the materials with which she works is a metaphor for the danger of being in the world while Black. Like the constant ruptures and arrests that structure Black life, the sculptures evoke the possibility of a break, of tearing and terror at any moment. These realities are also literally embedded in Weston’s work through photographs and textual inscriptions. Archival images and ones from her own life burrow into the folds of her sculptures alongside lines of her poetry. Weston was recently an Artist in Residence (AIR) at the Studio Museum in Harlem and was featured in the 2022–23 Studio Museum AIR show at MoMA PS1 in New York City. Her work un- (anterior ellipse[s] as mangled container; or where edges meet to wedge and [un]moor) (2024) is currently on view at the Whitney Biennial.

Zoë Hopkins

First of all, massive congratulations on your recent bevy of awards, the announcement of your gallery representation with Jack Shainman, and of course the Whitney Biennial. There’s a whole world of things to celebrate and congratulate you on.

Charisse Pearlina Weston

Thanks. It’s been a whirlwind, but more like a quiet whirlwind.

ZH

To get started, I want to ask a question about your Queens Museum exhibition in 2022. You once told me a story about a glass sculpture in that exhibition shattering halfway through the run of the show. That state change feels indicative of the way your work is bound up with unpredictability and risk. What kind of questions do working with glass allow you to express?

CPW

Glass has been an interesting and generative material for me because of its fragility and the danger inherent to its breaking; I’m intrigued by the omnipresence of collapse implicit within its materiality. Even a sculpture with the most stable foundation can falter. The piece you’re referring to, to lift the flesh of its flesh, the bone of its bone (Brockton Trial Court, June 3, 2020); after collapse, shattered because of an atmospheric shift in the gallery that caused its lead base—which supported a hot-folded pane of glass flanked by another slumped panel with a photograph from one of the 2020 BLM protests affixed to it—to soften and shift under the weight of the glass it held. As a result, the balancing pane fell and shattered. I then reconstructed that component and incorporated the new iteration back into the sculpture alongside the shards of the original pane that had not been disturbed. So, the meaning of the piece—a balancing of a formed, delicate body atop an already compromised foundation against the backdrop of protest—expanded to include not just the possibility of collapse but the actual instance of it through the presence of the shards.

One of the things that attracts me to glass is that its state change can represent the instability of meaning as well as the possibility for a new formation. I think about it in terms of making a way out of no way or conjuring an otherwise, through and in spite of the event of breaking. And then, of course, I think of the ways that working with these types of materials—lead, glass, and concrete—and contending with their instability and fragility runs counter to the ways we think about artwork as a finished commodity. I like to imagine leaning into these attributes as a quiet resistance to some of the parameters of the art market and to the overarching societal insistence on an irreversible completion that fixes things, people, and meaning in place. It’s much harder to own something that shifts form because it risks slipping through your fingers.

Charisse Pearlina Weston, to lift the flesh of its flesh, the bone of its bone (Brockton Trial Court, June 3, 2020); after collapse, 2022, slumped and enfolded glass, photographic decal, etched text, lead. Photo by Charisse Pearlina Weston. Courtesy of the artist.

ZH

Glass is of course also transparent. Yet in many of your writings and in the conversations I’ve had with you, words like opacity and withholding have come up, which is an interesting counterpoint to the material transparency of glass. What does that tension between opacity and transparency yield for your work?

CPW

I’ve spent the last few years researching the symbolic and material registers of glass in modern and contemporary society. Historically, transparency has been imagined as an aspirational ideal: it is supposedly capable of transforming our world into one without secrets. Transparency renders us, the whole of our interiors, open and legible. At the turn of the twentieth century, in a world still reeling from the aftermath of a world war as it was on the cusp of another, there was this prevalent fantasy that glass, as a new architectural material, could make manifest transparency in the built environment. The hope being that this new architecture would engender a different kind of understanding of each other that would ultimately lead to less war and conflict. Now, we see this is not the case at all; in fact, glass is one of the most important materials in surveillance technologies. This archaic interpretation of transparency benefits only a certain group of people. A lot of the work that I do with glass is about inverting transparency. So, I layer and reuse material and withhold visual access to certain components of the work, creating an architecture of interior life. Édouard Glissant writes about the Western obsession with transparency and unmitigated access that only essentializes the Other. It’s a kind of access that masquerades as an intimacy with those around us, but this knowing ultimately functions as a justification for violence that’s enacted on other people, as if to say, Because I know you, your desires, your sins, you deserve what I’m giving to you.

ZH

Precisely. Glissant also writes about how transparency and globalization occasion a flattening of difference or a universalizing reduction of cultural complexity to smooth, uniform invariability. It’s interesting, to that end, that your sculpture so often involves curvature. The glass snakes, twists, and turns. What brought you to that vocabulary of curvilinearity?

CPW

Initially with these curves, I was really interested in enfoldment as a way of creating another kind of interior and a space for concealment. I was contextualizing the fold as a kind of heterotopia, in a way. But recently, I’ve been thinking of the fold more as a form of repetition, which is already an element of my work. I am thinking of the fold as the instance of the body turning back into itself to repeat itself or an unarticulated part of itself.

Installation view of Charisse Pearlina Weston, of the. (immaterial. black salt. translucence), 2022, text on vellum, photographic decals on slumped glass, handmade wooden benches from Black Metropolis, produced by Robert Weston Sr., dimensions variable. Hessel Museum of Art, Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York. Photo by Olympia Shannon. Courtesy of the artist.

ZH

Your practice is research-based and archival. I’m curious to know where your research begins?

CPW

I begin my research with a specific question or topic in mind, which inevitably opens out into something else. It’s like a spreading vine. For instance, looking at the material history of glass is what led me to looking at surveillance technologies, which led me to the broken windows theory, which led me to make work about Occupied Look, a 1980s initiative led by the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development that involved installing decorative window decals on abandoned buildings in the Bronx. It all unfolds slowly in this way.

ZH

I really appreciate how your practice manages to be so entrenched in research and dense with history, while also being suffused with poetics. We’ve talked about the conceptual poetics of your work, but there are also literal lines of poetry subtly inscribed or etched in your sculptures, particularly in the glass. Can you share a bit about your relationship to poetry and how you came to involve text in your art?

CPW

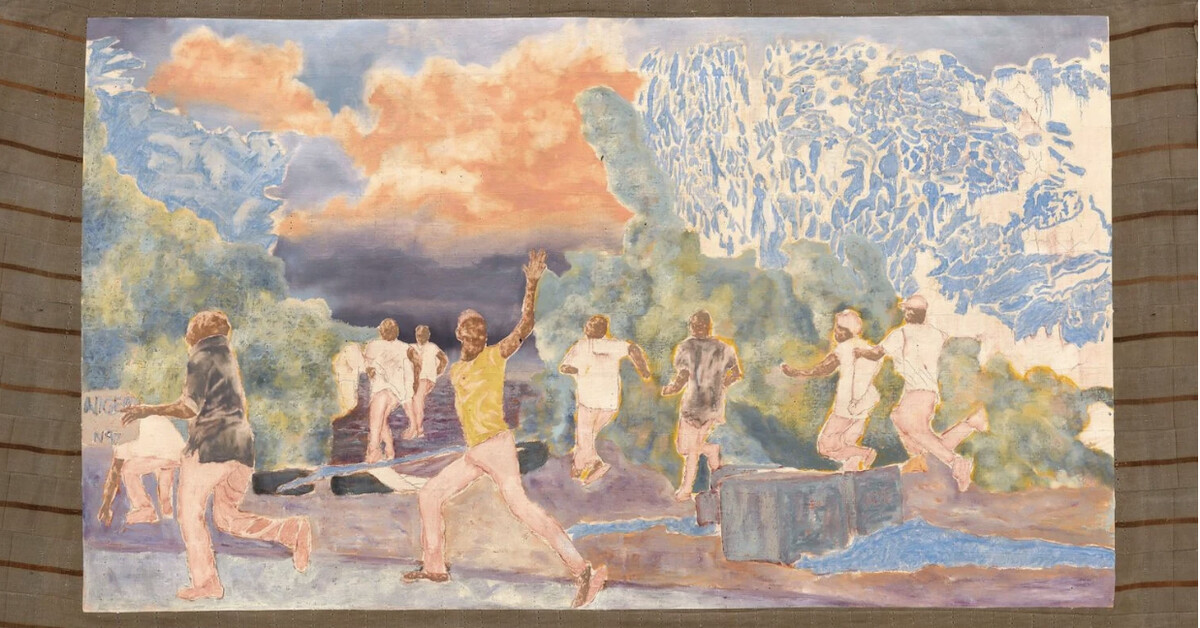

I’ve always been really interested in writing, but it took me a while to see how it could manifest itself in my work. It started with two installations I did at Project Row Houses in Houston in 2014 and 2015. Both were entirely driven by a poetic text, which really opened my eyes to poetry and how I could use it to reinsert Black experience into my work, especially insofar as the visual lexicon of my work was and still is rooted in conceptualism and abstraction. From there I started doing a photographic series where I layered photos with semi-autobiographical text fragments printed on vellum. Later, I began incorporating sheets of glass into that work, with the most recent example of that series being the installation of the. (immaterial. black salt. translucence) (2022) that I did for the exhibition Black Melancholia, curated by Nana Adusei-Poku at Bard College in 2022.

Installation view of Charisse Pearlina Weston, un- (anterior ellipse[s] as mangled container; or where edges meet to wedge and [un]moor), 2024, laminated tempered glass sheets from the air, whiskey, dust of [a] tomorrow, and stainless-steel hardware. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City. Photo by Ron Amstutz. Courtesy of the artist.

ZH

Finally, I want to ask you about your work in the Whitney Biennial. The piece strikes the eye—and the body—quite forcefully and almost immediately as visitors step off the elevator. We’ve talked about your floor-based sculpture, but this work hangs overhead. It’s also flat and emptied of many of the elements that we’ve discussed, like photography, curves, and poetry. Can you talk a bit about these dynamics of form and display?

CPW

The piece at the Whitney is very much about an impending threat. I have been thinking of it as the pause before the moment of collapse. Like the breath one takes in just before something life-altering happens—a kind of bracing. It’s suspended in the air but hung quite low, so you experience a specific kind of tension, and pressure, and anxiety in spite of the fact that its infrastructure—a series of aircraft cables and stainless-steel hardware—is visible.

ZH

I was just about to use the word pressure. There’s an inevitable sense of tension in the feeling or awareness of the sculpture looming over your head, particularly since it’s made of glass. It also returns us to our earlier discussion around the atmospheric dimension of your practice: because the glass is tinted, the atmosphere of the gallery becomes shadowy, darker.

CPW

Yes, exactly. To address the second part of your question around the difference in form and material, this piece is an evolution of a series of installations that I was doing—I guess, that I continue to do—alongside the smaller sculptures. Those were balanced glass installations consisting of rectangular sheets of glass situated in space with the intention of shifting the architecture and volume, at a much smaller scale, of the space. To me, those pieces were important because they were a way for me to really engage with this idea of risk and precarity, the possibility of collapse, and the fragility of the material. The Whitney piece is a large-scale version of that, but the challenge for me was to try to figure out how to keep all of those elements intact while one is aware that it is suspended in a very particular way.

Charisse Pearlina Weston’s work can be seen in the Whitney Biennial 2024: Even Better Than the Real Thing at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City until August 11.