Making Connections Through Clay at Frieze London

The New York Times / Oct 3, 2024 / by Ray Mark Rinaldi / Go to Original

The gallery Patron will display works by Noé Martínez from his “Racimo” (“Bunch”) series at Frieze London. His hanging works often include small ceramic pieces that reference the rattles and musical instruments found at archaeological digs. Evan Jenkins, via the artist and PATRON Gallery

When Frieze London invited Pablo José Ramírez to curate a themed section for its 2024 edition, he knew right away that he wanted to feature clay. He already had a list in his head, he said, of ceramic artists whose work he hoped to show together.

Some of them he knew through his current position as a curator at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, others from his previous job as curator of Indigenous and First Nations art at Tate Modern in London. Some were Indigenous, and some were not.

But all of the artists were thinking alike, in a way: they were reaching back into the past, and drawing upon pre-colonial traditions once commonly used to make everyday bowls, tools and totems, to create ceramics that addressed current topics of concern for many contemporary artists, like migration, human displacement and personal identity.

“It’s contemporary art, but at the same time it’s ancestral art, but at the same time it’s material culture,” said Ramírez during a recent video interview.

“Smoke,” as the section is now titled, will feature 11 artists, represented by eight galleries. The galleries will be lined up together within the fair, but separated by transparent fabrics so that they appear to connect into a single environment — a departure from the usual rows of walled-off dealers that visitors more often encounter at fairs like Frieze, Art Basel and the Armory Show.

“It will be a little more like an art exhibition and a little less like a booth situation with all these little white cubicles,” said Ramírez.

That setup is possible, Ramírez pointed out, because most of the ceramics in “Smoke” are three-dimensional objects best displayed on pedestals or directly on a floor. Unlike most galleries that sell at art fairs — and that tend to focus on paintings — his galleries did not need walls to begin with; the moment was waiting to be seized, he said.

But uniting all of the works in one space also helps him drive home a point he wanted to make with “Smoke,” and that is about ceramics itself as an art form.

The artists in the exhibition who are not Indigenous all happen to be migrants —people who moved from their birthplace to another country. Ramírez believes there is a connection between the objects made by the Indigenous artists and those made by expatriate artists that is enabled specifically by the medium they work in.

Clay comes directly from the earth and because of that has a singular power to communicate profound stories about land itself — land inhabited, lost, left behind— and that is what these artists are doing, implicitly and abstractly, through their attempts to “explore both diasporic and Indigenous histories,” he said.

That link makes room on the roster for ceramists like Noé Martinez, an artist from Mexico, whose kiln-fired pieces, presented by Patron Gallery of Chicago, are inspired by objects recovered from archaeological sites in La Huasteca, where his ancestors are from. The centerpiece of Patron’s display will be selections from Martinez’s “Racimo” (“Bunch”) series, for which he brings together small ceramic pieces into hanging works that reference the rattles and musical instruments found at digs.

But the concept behind “Smoke” is also wide enough to include artists like Lucía Pizzani, a Venezuelan expatriate now living in London. Pizzani is not Indigenous, though her work borrows from long-held traditions of her native country.

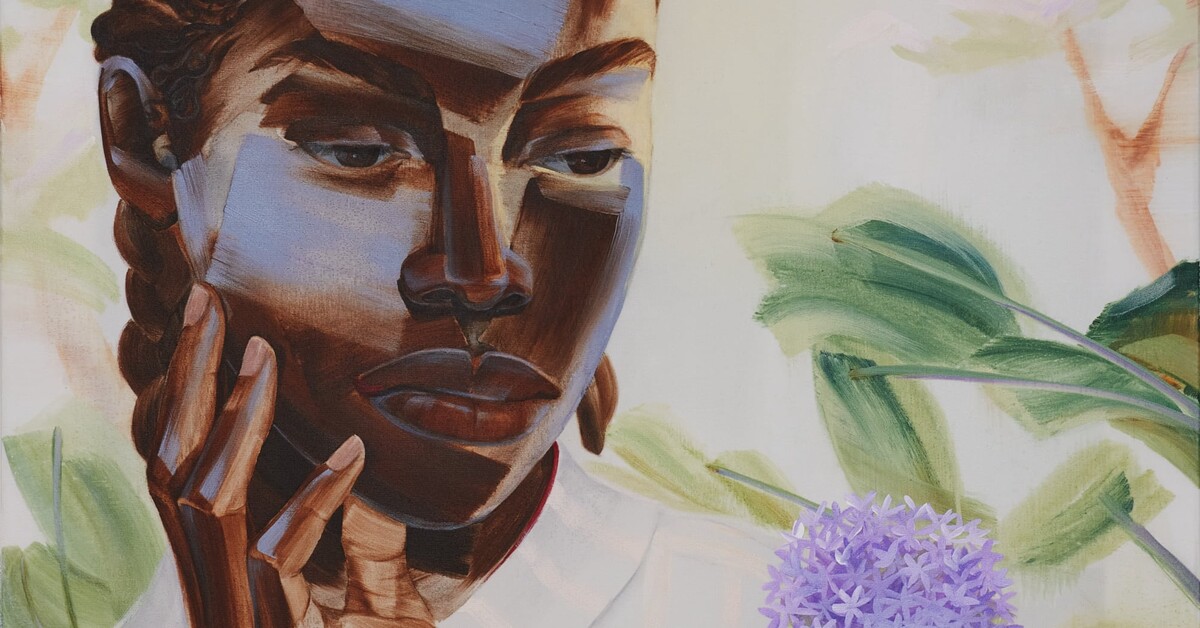

The Cecilia Brunson Projects will show works at Frieze London by Lucía Pizzani, including a series of totem-like objects like this one, “Flora Totem Pino” (2023). via the artist and Cecilia Brunson Projects

Several of the pieces she will exhibit, with Cecilia Brunson Projects of London, were created during a recent residency at El Cercado studio, located on Isla de Margarita, an island north of the Venezuelan mainland, where pre-Hispanic ceramic making is still practiced. The works are made with local clay, which is shaped, dried and then fired over an open flame, rather than in a kiln.

She will also show a series of totem-like objects she made of English clay for Whichford Pottery, in Warwickshire, some 80 miles from London. Pizzani imbues her artworks with a timeless aura by decorating them with symbols from nature, including imprints made from plants.

“I try to find symbols and things that connect us as humans, that you can find throughout history and in different geographies,” she said during a video interview. “So, like the snake, the spiral, a lot of the imagery that I use, maybe you can place it, but maybe not, and it’s something that unites us in the unconscious.”

Other artists presented in “Smoke” include Adán Vallecillo (via Galería Extra of Guatemala City), whose work examines social and environmental impacts of mining in Honduras where he lives; and Karla Ekaterine Canseco, who lives in Mexico City, and Roksana Pirouzmand, who lives in Los Angeles (co-exhibited by Murmurs gallery in Los Angeles). Canseco’s ceramics look at the lore behind the popular Mexican dog breed Xoloitzcuintli, while Pirouzmand makes wall-mountedpieces that resemble female forms and explore themes of memory and violence.

In his art, Adán Vallecillo examines social and environmental impacts of mining in Honduras where he lives. His collages are expected to be shown by Galería Extra of Guatemala City at Frieze London. via the artist

Ramírez handpicked the artists who will appear in “Smoke,” which is different from the way most art fair operations come together. More often, galleries apply to rent booths, bringing the artists of their own choosing — people they want to promote and think they can sell — to the event.

Turning that process around meant convincing the galleries in the section to follow his curator’s instincts, and to feature work that might not have been what they had in mind for the Frieze London audience, and then to showcase that work as part of a cooperative and somewhat experimental effort.

“It’s about trusting the gallery, and also about the gallery trusting your proposal. Because for the gallery, it’s a big investment,” said Ramírez.

Emanuel Aguilar, Patron Gallery’s co-owner, said such invitations do require a lot of consideration. Galleries need to adjust their marketing, and artists need to prepare a significant amount of product in time for any show they participate in.

“We talk to the artists, and if it makes sense in every possible way — whether that’s conceptually, or bandwidth-wise for both the artist and for the gallery — we accept the offer,” he said.

But, in its chosen artist, Martinez, Patron felt it had the perfect fit, and the gallery is throwing itself into the moment.

Because Martinez sometimes finds relics that inspire his art along beaches in southern Mexico, the gallery is bringing in piles of sand for the fair, which it will use as a surface on which to display Martinez’s ceramic objects.

Aguilar said he also liked the idea of being part of something that shuffles the ordinary art fair experience. Galleries and fairgoers alike often complain about the sameness of these events, even across international borders.

“We’re an industry that supposedly is about ideas and innovation and inspiration, and we do very little of that, in particular with our trade fairs,” he said.

“Smoke,” with its strong theme and unusual style, was something he wanted to support, he said.