Caroline Kent: Confidence On Canvas

Chicago Gallery News / Aug 26, 2024 / by Alison Reilly / Go to Original

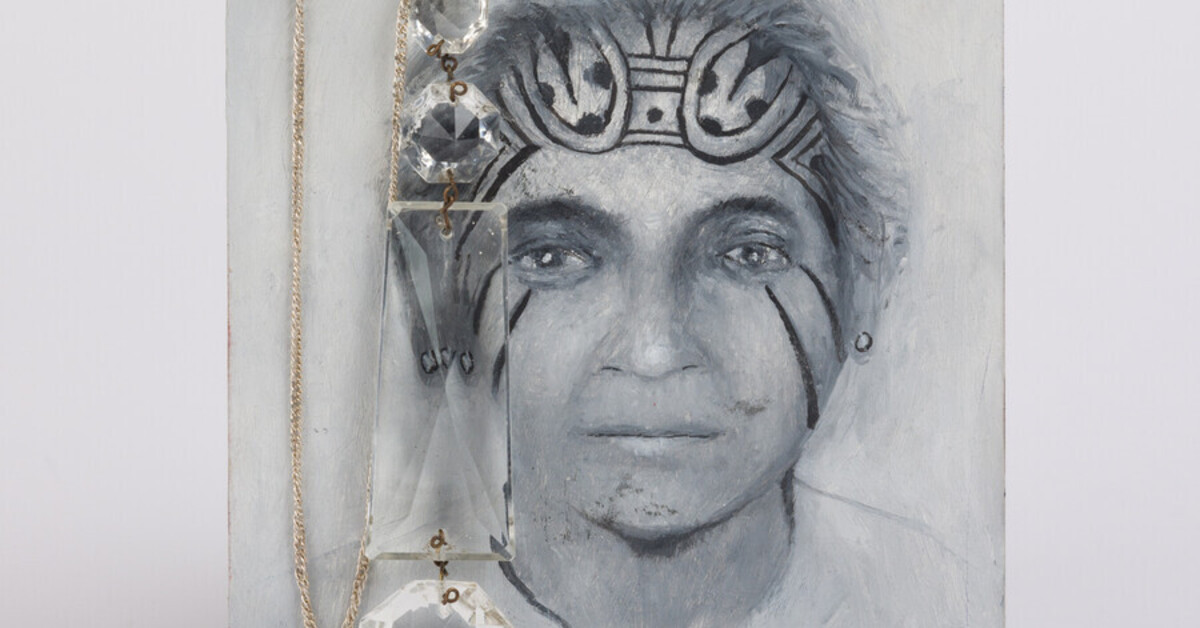

Caroline Kent. Photo: Evan Jenkins.

When Caroline Kent and I spoke in late July, she was attending a writing workshop at Northwestern University. Working from what felt like a Victorian-era study at Scott Hall, she cherished the opportunity to sit with her ideas, without interruption. By the third day, she said she was hitting her stride and started writing as soon as she arrived in the morning. An athlete who found art as an undergraduate student at Illinois State University, Kent uses writing to gain clarity about her visual art practice. She trusts the process of making, values hard work and practice, and has an acute understanding of herself. Her compelling abstract paintings, works on paper, and installations showcase her own visual language. This fall, through a collaboration with Amtrak, Kent will present her work in a large-scale public installation at Chicago’s Union Station.

CGN: Could you tell me about your own writing?

Caroline Kent: My relationship to writing comes out of having kept a journal for a long time and using it as a creative space, even in how I once documented my days. I don’t have that practice anymore. But when I get time to write, I try to always write about my practice, always thinking of it having legs and arms that can go in different directions.

CGN: How does your writing affect your visual art?

CK: My practice has painting as its center but branches off into text-based works or ideas around language. And more recently, I’ve been using this writing workshop at Northwestern to work on a one-act play, to write expanded ideas around different projects like Victoria/Veronica. Writing helps deepen and bring breath to the work that then can move outside of painting and speak to other mediums, whether that’s installation or considering an entire room as opposed to an art object.

Right now I’m working on a project for La Trienal with El Museo del Barrio (New York) that’s coming up this fall. I was invited to present some of my work, and they gave me a wall. Am I going to hang an art object on it? Am I going to paint something on it? The writing ends up helping me make formal decisions and choices about how I want the work to function in the presentation of the exhibition, whether it’s the abstract language painted on a large canvas or whether it needs to be reduced down to simple shapes on Belgian linen. Those kinds of distinctions are interesting for me to be really selective about when I am presenting the work– what kind of narrative do I want to build in the work and what do I want to say this time?

CGN: When you’re in your studio, how do all the different media that you’re working with come together?

CK: In the studio, what I really appreciate is that I can work on the wall on something large and then I can move immediately and look over to the table. They’re all in the same room. And even when I’m making works on paper, I like to have them sit out in the room together, because they start to speak to one another. What happens on a larger canvas ends up happening on a work on paper. They all end up getting influenced.

Caroline Kent: Space | Shadow | Script, PATRON Gallery, Chicago, September 2022. Photo: Evan Jenkins.

CGN: What is a typical day in your studio?

CK: My studio is in my home. In the morning, once I get in there–I learned this trick from someone I don’t remember where, but they told me, if you have a problem when you first go into your studio in the morning of knowing where to start, it’s always good to leave something for yourself to do the day before so that you can go in and start without having to think and make decisions, but continue something. I always try to leave some painting for myself to do.

It’s my warmup. It gets me into it.

I’ve got headphones on, and typically I’m listening to / watching a BBC crime drama. I’m not always looking at the screen, but I’m listening to the dialogue and it gives my mind something to grab onto while I’m working. I usually work until lunch, then I break and come back and check email and things like that, but I get back into the studio. I would say on average, it’s about a five- to six-hour day. Then it goes back to kids, husband, life. All the other stuff that’s so easy to get distracted by when you’re in your house. I try to stay pretty focused.

CGN: What are some of your earliest memories making art?

CK: This is a funny question because there are two things that stick out to me from my childhood. One of them is that I used to leave writings around the house–just scribbles on a notepad. Recently, my mother has been sending me these as she’s been combing through boxes and bins of things. We had a typewriter at one point, and I remember typing up these conversations about my sister’s boyfriend and asking what his intentions were. I read them now and I’m thinking, this is exactly somehow related to what I’m doing now.

And then another thing while I was growing up–this is much more abstract. I didn’t have a name for it. There were moments like during a car ride across the flat land of driving from Sterling, Illinois to Rockford, staring out at cornfields and bean fields. I would have the strangest ideas about things I would do. And I can’t give you an example because they’re so weird for me now, but I remember later on in life, recognizing a lot of these abstract ideas I had really fit into the language of art. Those are some of my earliest memories.

CGN: You grew up in Sterling?

CK: I went to elementary and high school in Sterling,and my parents still live there.

CGN: And Rockford, you visited?

CK: My grandparents lived in Rockford, and so my father would drive us there all the time. There were six of us in a station wagon, four girls in my family. And we would all drive to and from Rockford.

Caroline Kent, A witness comes, beckoned from beyond, 2024, Acrylic on canvas. Photo: Evan Jenkins, Courtesy PATRON Gallery.

CGN: You said leaving notes for yourself relates to what you’re doing now. Could you talk more about that?

CK: The notes were these small scenarios. They’re little snippets of theatrical descriptions of life. Some of the things that I’ve even been working on more recently–I have a series called Typewriter Works, where I pair different descriptions of characters with abstract paintings on paper. I make a painting, and it dries on the paper and then I feed it through the typewriter. In this way, I am synthesizing a character that I have seen in a film or in my imagination. I think that’s the connection I can see clearly. When I was younger, I was inventing a lens on how I was perceiving myself, my teachers, how my parents viewed me, writing about my sisters’ lives and making these funny, inflated, idealistic writings.

CGN: When did you start identifying as an artist or make the decision to be an artist?

CK: I feel like I was late in the game in some ways. Art didn’t awaken in me until I was in college. I was at university, and it was there that I walked into a gallery. My twin sister and I, we would go around and check everything out from the theater department to watch plays, to the art gallery, coffee shops. It was the nineties, the alternative scene. I remember the nineties aesthetics in art. Collage was big. I have such a clear idea of going back to my dorm room and starting to work in collage. That was the moment when I was like, this is the thing I want to do, but I didn’t know how to get there until a mentor friend of mine guided me to really consider making art my major. And I remember thinking, but I don’t know how to draw, I don’t know how to paint, and just telling myself, okay, I guess I’m just going to be the artist who learns when they’re 20.

That kind of confidence, I would call it confidence looking back because it was such a big decision to tell yourself, when you feel there’s a deficiency, maybe I should have been doing this since I was three or four. But I think it came out of athletics and being able to push my body and know what pain was, getting to the other side of physical challenges. I think because of track and field, it helped me decide, well, I guess I’m going to do it in a non-traditional way.

CGN: I love that. How long do you think it took you to get confident in your own skills? Was it something you picked up immediately?

CK: I invited it immediately and it brought a satisfaction, but I don’t think that I felt confident in art making. I wasn’t thinking about it because I did feel such a freedom with it. I finished up my undergrad degree and I had taken a lot of intro classes, but after that I took seven years off before I went to grad school. In that interim time I ran into a charming professor from Illinois State, Harold Boyd, who I really adored. I ran into him on the street in Minneapolis. I said, I’m about to go to the Peace Corps, and what do I do with art? How do I continue making it if I’m doing this completely other thing? And he said, well, you need something to make art about. You need some depth, you need experience, you need life, and so don’t consider this not conducive to your art practice. That was so helpful. The confidence came probably after graduate school. That’s when I felt confident and understood what I was doing. And to be honest, I wasn’t pursuing confidence, but I was getting confident by really understanding my own practice and developing it and getting legs under it.

Caroline Kent: This Space for Correspondence, Casey Kaplan, New York, November 2023.

CGN: How was your experience being part of the Peace Corps in Romania?

CK: It was a super interesting time because it was such a contrast to American life. I knew that I was feeling a certain way about American culture, and I wanted a kind of diversity that I only saw watching international films. Going [to Romania] gratified this desire to have a very different kind of experience other than an American one, though it also was very challenging. It was hard to be away from the familiar, but it helped me grow and experience a lot of really wonderful things, not only the foods and the culture and the people I met and the children I taught, but the landscape was incredible, as was visiting monasteries and learning another language and going to these Romanian Orthodox churches where most people stand the entire service. Going through the forest and traveling with friends for an hour, and then running into an old woman there who’s gathering up pussy willows, giant ones – I was like, ‘Where am I?’

CGN: How did you decide to pursue an MFA and go to graduate school?

CK: I had been living in Minneapolis for a while and I had traveled, lived abroad. I’d come back home and had a temp job to reintroduce myself back into American life. I knew I needed something more. That was the moment when I was like, okay, what do I want to do? I’m at another kind of crossroads. I liked art, but I had been out of any connection with the contemporary art world. I ended up taking advanced painting and drawing at the University of Minnesota. I was really incredibly zealous. I was excited, and I overproduced. My professors saw something in that and were like, you really should consider the MFA program. So I put together my portfolio. Three people were accepted that year for painting and drawing, and I was one of them. That was the most encouraging and exciting news. I still remember to this day the phone call I received when they told me I was chosen out of 130 applicants. I really felt it marked a moment in my life that illuminated a path forward.

CGN: How long have you been in Chicago, and how has living here affected your practice as an artist?

CK: I’ve been in Chicago since 2017. I was living in Minneapolis, and it had a rich art community, but I was ready for more. I think any artist that works in a smaller city, at some point, you either make a commitment to be there for the long term or you start getting the itch to move. My husband was offered a position here at UIC in the art department. It expanded our practices in many ways. Part of that was more visibility, connecting to a larger network of artists. It took me a couple of years before I really got comfortable here in Chicago and maybe even longer. I moved to Garfield Park and the intensity was of high contrast. It took me a while, but there are so many great things that I love about Chicago. It was great to see such diversity having come from Minnesota. And the city has a kind of energy, seeing Lake Michigan, there’s nothing like it. The cultural history here, there’s still so much for me to discover in Chicago.

Caroline Kent: A short play about watching shadows move across the room, The Queens Museum, Queens, NY. December 2023. Photo: Hai Zhang

CGN: You mentioned the upcoming triennial with Museo del Barrio. What else are you working on?

CK: I’m working on a project for Amtrak right now, and it’s going to debut at Union Station in the fall. It is a vinyl mural project that I’m designing for interior windows in their downstairs space. I feel like it’s really going to transform Union Station. I’m also working on a commission with the U.S. Embassies Project, a program where artists are commissioned to make work for different U.S. embassies around the world. Then I’m making work for my own practice. Sometimes as an artist, my artwork leaves my studio so fast. I don’t live with it. If I have an exhibition coming up, and there’s some really lovely works that I want to live with for a while. Well, it goes to the exhibition. And if it does get placed with a collector or an institution, it never comes back. And so what did I have? Six months with that piece, that’s it. It’s nice to always be making work that will live with me, that will stay in the studio, that I can keep, that I can continue to think about and be inspired by. I’m often making work for my own personal archive.

CGN: Do you keep an archive of your work?

CK: It can be tricky. But I’m just getting better at learning to save things and hold on to them. Not only for myself, but thinking about what I will leave to my children. I have three children and I want them to keep the archives of their parents’ work.

CGN: Are they interested in art at all?

CK: My daughter, Nina is eight, my son, Kent is ten, and Ysabella my stepdaughter is the oldest, she’s 19. They were each very creative when they were young. We definitely are a home of makers. They’re always making something, gluing something, whether it’s my son making a contraption for Legos, or my daughter is making bookmarks, painting or gluing something together. She’s a sewer. My youngest, Nina, is really in a creative moment with sewing, crochet, drawing, making, all of it.

CGN: That’s great to kind of watch them experiment with all those things.

CK: It’s helpful being parents that are makers, because when your kids are like, ‘Oh, I want to do this thing.’ We just go into our studios and we’re like, ‘All right, let’s do it. What do you need? We’ll do it this way. We’ll build it.’ Those are really great teaching moments.

CGN: What about teaching at Northwestern? How has that affected your art practice?

CK: As an artist, it can be such an isolating, singular path. When you’re making in your studio and you’re trying to exhibit, it can feel like your peers aren’t always on the same path with you. Teaching is such a great balance for my soul, because it gives me opportunities regularly to give back and pour into other students and share with them and break bread with them. In a way, that feels counter to thinking about the art market. It’s a hard topic for a lot of artists to talk about, because it’s about money in exchange for art. What can be rewarding is when I have an exhibition–for example, I have a mural up at the Queens Museum right now–and I can talk about that experience and share what I learned and gained from working with an institution and be able to share that with graduate students. When I can give in a way that can plant seeds and inspire something alongside academia, that is really a rich and holistic piece of my life.