What to See in N.Y.C. Galleries in September

The New York Times / Sep 4, 2024 / by Will Heinrich and Travis Diehl / Go to Original

This week in Newly Reviewed, Will Heinrich covers Mike Cloud’s painterly sculptures, black-and-white photos by Joanne Leonard and Brittany Nelson, and Jeff Way’s endless color grids.

CHELSEA

Mike Cloud

Through Oct. 26. Thomas Erben Gallery, 526 West 26th Street, 4th floor, Manhattan; 212-645-8701; thomaserben.com.

Each of the six works in Mike Cloud’s spectacular show at Thomas Erben begins with a tall and narrow wooden frame leaning against the wall. Hanging from the top edge of every frame, which is angled to evoke a guillotine, is a large triangle or star roughly constructed from broom handles. Colored pencils, No. 2 pencils or wooden spoons jut out from many of the handles’ intersections, and a mop head made from shredded canvas is attached to each corner.

Cloud cuts canvas to fit each of the stars’ interior sections and paints them with rainbows, pie charts and snowflake patterns in vivid, oily, impeccably chosen colors. He also glues on canvas hearts adorned with football-like rows of stitches and hamsa-like hands, which he turns to birds by painting on beaks and legs, as in a grade-school Thanksgiving project.

Another strip of canvas runs across the front of each piece, on which Cloud paints a web address from Wirecutter, The Athletic or The New York Times. They lead to such disparate articles as one about the ambassador of Israel’s wearing a yellow star to the United Nations and another explaining how to clean a smelly tent.

What’s astonishing about these pieces is how distinctly they still read as paintings, despite all these elements of sculpture, mixed-media collage, postmodern deconstruction and Rauschenberg-era expansion of the canvas. Cloud’s trick is that he uses those elements to expose the visual interest and untapped power of the sheer, painterly relationship between a flat canvas surface and a set of wooden stretcher bars.

CHELSEA

Joanne Leonard/Brittany Nelson

Through Oct. 19. Luhring Augustine, 531 West 24th Street, Manhattan; 212-206-9100; luhringaugustine.com.

How do you conjure a human presence without any humans? Consider this beautifully hung two-person photography show.

Joanne Leonard’s small, closely focused black-and-white photos include nary a human, though there is one cat and one row of uncanny doll hands. Shot and printed in the 1970s and 1980s, when Leonard was a working single mother, they show kitchen and laundry-room countertops in her home and others’.

But whether it’s the submissive slump of a half-empty packet of napkins, the jaunty tilt of an enameled dust pan or the gaping, orthodontic exposure of a couple of crowded dishwasher trays, each one of these tableaus offers as much personality as Marcel Marceau. There’s no doubt that these spaces are inhabited.

During a residency at the SETI Institute, Brittany Nelson used a hand-held spotlight and a medium-format camera from the early 1980s — it’s about as old as she is — to photograph the 42 dish antennas the institute uses to search the skies for alien life. Some are half hidden in shadow; others loom as large and white as some kind of cosmic egg. Unmistakable in all of them is a very particular sense of self-conscious loneliness, as you listen to the echo of your footsteps while crossing an empty room.

TRIBECA

Jeff Way

Through Oct. 5. Storage, 52 Walker Street, 4th floor, Manhattan; storageartgallery.com.

Sometime in the late 1960s, Jeff Way sprinkled pure acrylic pigment over a primed canvas and made a grid pattern with a chalk line. When he was satisfied, he fixed everything into place by spraying on medium. In one early example of the series, which he calls “eccentric squares,” the red lines are crisp and closely set so that despite the blue and yellow notes and the rust-colored fog that envelops the whole, the piece bears a clear relationship to the Cartesian serenity of 1960s minimalism.

Soon, though, Way turned up the tension with louder colors and a more widely spaced grid that left room for discrete, Rorschach-like clouds of pigment in every cell. A few times he emphasized the gritty, unresolved texture of his process by working in white on white. Sometimes the pigment seems to float and disappear; occasionally he cast down colors so thickly that the grid was hardly visible.

More recently Way has been painting grids with a brush or drawing them with colored pencils. “Jeff Way: Then & Now (1970-2024),” down the block from his longtime TriBeCa studio at Storage Gallery, includes a number of bright, plaid-like drawings and paintings just as electric as the older work. Way goes over and over every surface until the tiny bits of white left exposed are practically shooting out into the gallery.

CHELSEA

Mike Cloud

Through Oct. 26. Thomas Erben Gallery, 526 West 26th Street, 4th floor, Manhattan; 212-645-8701; thomaserben.com.

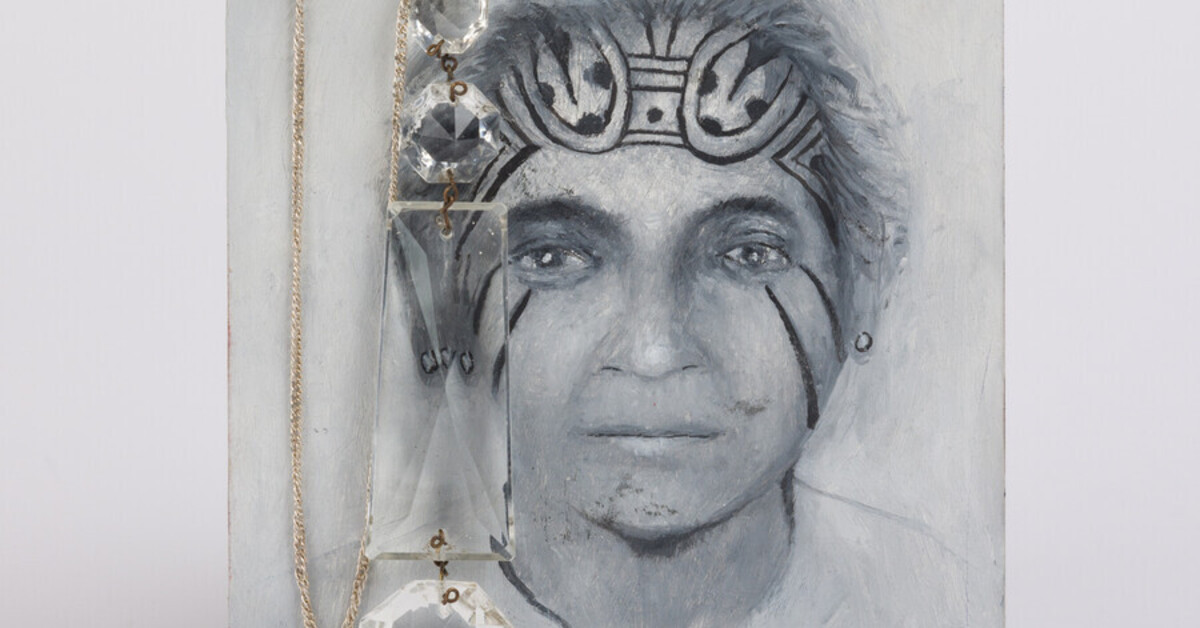

Mike Cloud, “Erdan Yellow Star of David,” 2024, oil on canvas, wooden broom sticks and cooking spoons, colored pencils and canvas strips. via Mike Cloud and Thomas Erben Gallery, New York

Each of the six works in Mike Cloud’s spectacular show at Thomas Erben begins with a tall and narrow wooden frame leaning against the wall. Hanging from the top edge of every frame, which is angled to evoke a guillotine, is a large triangle or star roughly constructed from broom handles. Colored pencils, No. 2 pencils or wooden spoons jut out from many of the handles’ intersections, and a mop head made from shredded canvas is attached to each corner.

Cloud cuts canvas to fit each of the stars’ interior sections and paints them with rainbows, pie charts and snowflake patterns in vivid, oily, impeccably chosen colors. He also glues on canvas hearts adorned with football-like rows of stitches and hamsa-like hands, which he turns to birds by painting on beaks and legs, as in a grade-school Thanksgiving project.

Another strip of canvas runs across the front of each piece, on which Cloud paints a web address from Wirecutter, The Athletic or The New York Times. They lead to such disparate articles as one about the ambassador of Israel’s wearing a yellow star to the United Nations and another explaining how to clean a smelly tent.

What’s astonishing about these pieces is how distinctly they still read as paintings, despite all these elements of sculpture, mixed-media collage, postmodern deconstruction and Rauschenberg-era expansion of the canvas. Cloud’s trick is that he uses those elements to expose the visual interest and untapped power of the sheer, painterly relationship between a flat canvas surface and a set of wooden stretcher bars.

CHELSEA

Joanne Leonard/Brittany Nelson

Through Oct. 19. Luhring Augustine, 531 West 24th Street, Manhattan; 212-206-9100; luhringaugustine.com.

Joanne Leonard, “Ann Arbor, MI,” 1976-85, gelatin silver print image. via Joanne Leonard and Luhring Augustine, New York

How do you conjure a human presence without any humans? Consider this beautifully hung two-person photography show.

Joanne Leonard’s small, closely focused black-and-white photos include nary a human, though there is one cat and one row of uncanny doll hands. Shot and printed in the 1970s and 1980s, when Leonard was a working single mother, they show kitchen and laundry-room countertops in her home and others’.

But whether it’s the submissive slump of a half-empty packet of napkins, the jaunty tilt of an enameled dust pan or the gaping, orthodontic exposure of a couple of crowded dishwasher trays, each one of these tableaus offers as much personality as Marcel Marceau. There’s no doubt that these spaces are inhabited.

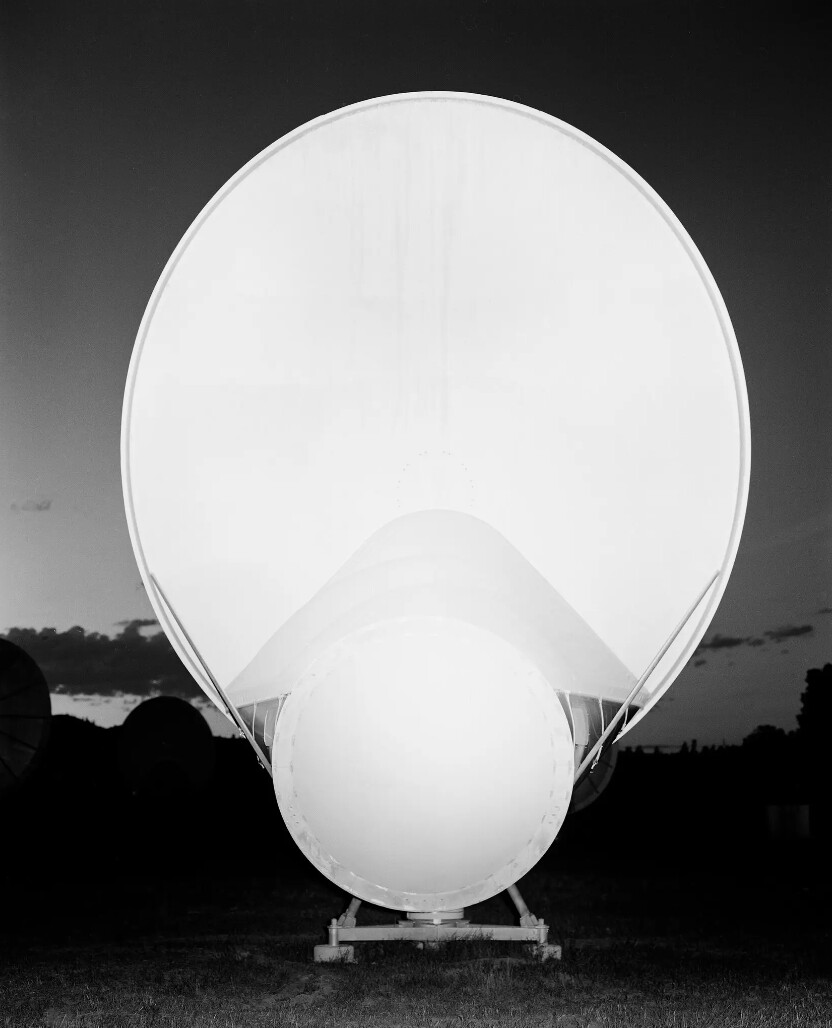

Brittany Nelson, “Overexposed Telescope,” 2024, handmade gelatin silver print image. via Brittany Nelson, Luhring Augustine, New York and Patron, Chicago

During a residency at the SETI Institute, Brittany Nelson used a hand-held spotlight and a medium-format camera from the early 1980s — it’s about as old as she is — to photograph the 42 dish antennas the institute uses to search the skies for alien life. Some are half hidden in shadow; others loom as large and white as some kind of cosmic egg. Unmistakable in all of them is a very particular sense of self-conscious loneliness, as you listen to the echo of your footsteps while crossing an empty room.

TRIBECA

Jeff Way

Through Oct. 5. Storage, 52 Walker Street, 4th floor, Manhattan; storageartgallery.com.

Installation view of “Jeff Way: Then & Now: 1970-2024” at the Storage gallery. via Jeff Way and Storage, New York; Photo by Kea Kapoi

Sometime in the late 1960s, Jeff Way sprinkled pure acrylic pigment over a primed canvas and made a grid pattern with a chalk line. When he was satisfied, he fixed everything into place by spraying on medium. In one early example of the series, which he calls “eccentric squares,” the red lines are crisp and closely set so that despite the blue and yellow notes and the rust-colored fog that envelops the whole, the piece bears a clear relationship to the Cartesian serenity of 1960s minimalism.

Soon, though, Way turned up the tension with louder colors and a more widely spaced grid that left room for discrete, Rorschach-like clouds of pigment in every cell. A few times he emphasized the gritty, unresolved texture of his process by working in white on white. Sometimes the pigment seems to float and disappear; occasionally he cast down colors so thickly that the grid was hardly visible.

More recently Way has been painting grids with a brush or drawing them with colored pencils. “Jeff Way: Then & Now (1970-2024),” down the block from his longtime TriBeCa studio at Storage Gallery, includes a number of bright, plaid-like drawings and paintings just as electric as the older work. Way goes over and over every surface until the tiny bits of white left exposed are practically shooting out into the gallery.