Ripped

CCQ Magazine / Apr 18, 2016 / by Rhiannon Lowe / Go to Original

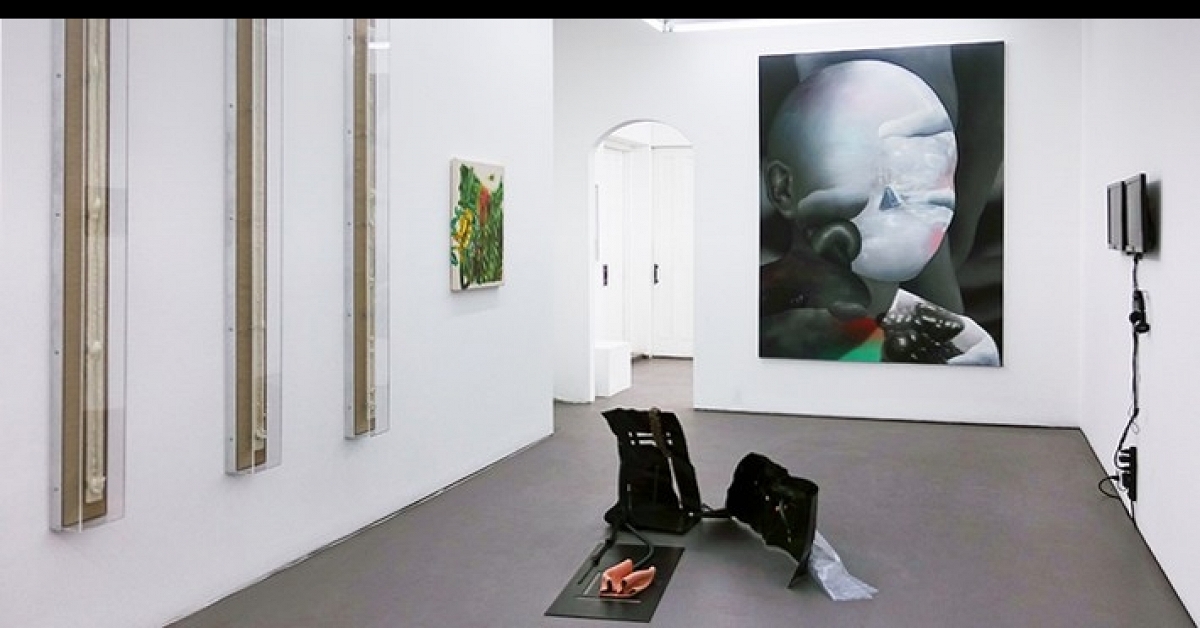

Chicago-based Samuel Levi Jones subverts world views perpetuated by old law books and encyclopedias into aesthetically intriguing touchstones for debate. He talks to Rhiannon Lowe as he prepares for his solo exhibition at The Arts Club.

Rhiannon Lowe:What led you to start working on issues surrounding the injustices meted out to African Americans in the US?

Samuel Levi Jones:I had a great-uncle who was lynched in his (which is also now my) home town in 1930. My father had to learn how to swim in the river as a child during the ’50s, because he was not allowed in the local pool. Then, there’s my own experience of being profiled [by the police], pulled over and harassed, together with the wider and continual marginalisation of any persons due to race, gender or class; it’s all led to my addressing such issues.

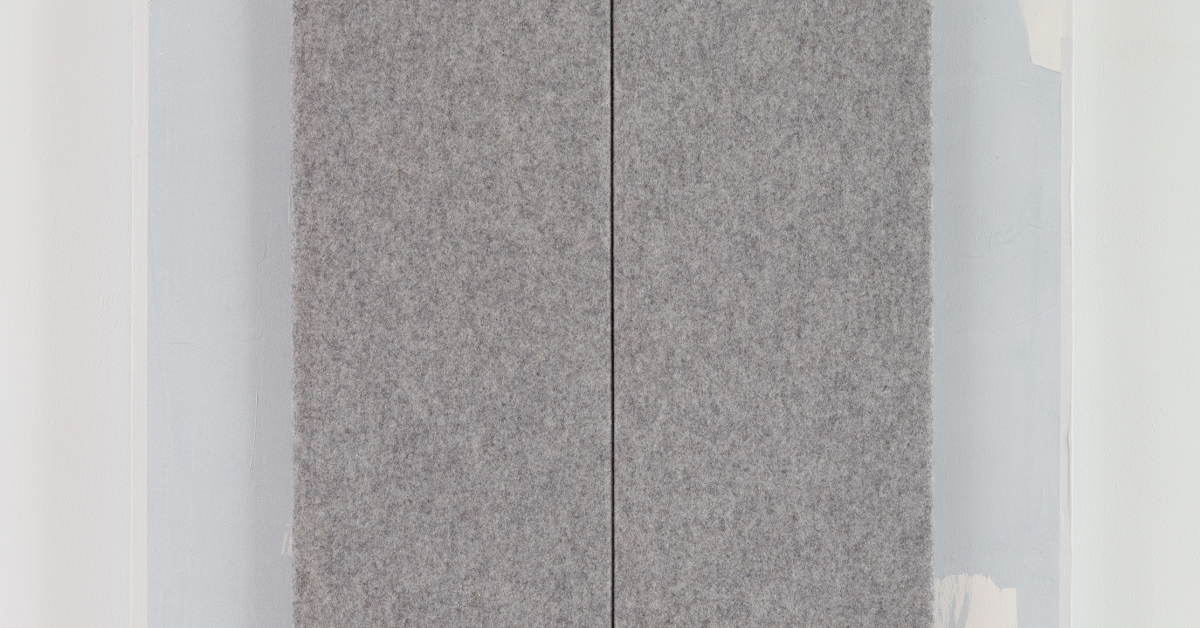

RL:What is the nature of the books you deconstruct?

SLJ:The books are symbols, signifiers of systems of power. The encyclop3â„4dias represent a form of control of knowledge. I’ve been living with the material of the books after I have deconstructed them; they have been here, lying around on the floor, for a year or more. The material is very specific, especially the law books that I have been working with. The very nature of the material is such that it has a direct link to the things that consume me and I feel need to be addressed. I like coming into my space and it’s all there; I’m living with the material of my practice.

RL:Your work addresses societal issues. How can making material canvases in the age of Twitter contribute to the conversation around the struggle for equality?

SLJ:Social media may have a louder voice and a broader reach, but it can be confusing. Social media is not always an agent for change. The canvas is not a solution on its own; it’s a gesture that helps with sharing thoughts and ideas. I was aware of the issues that I address well before the existence of social media. Social media informs me of events that are a result of the issues. They are simply symptoms of a larger problem. Most times, the issues that I see in social media anger me. Art calms me down.

RL:Have you changed vehicles of expression since you started practising?

SLJ:In my early 20s I was connected to the art world by my camera. It was a tool that I used, allowing me to navigate my life events and thoughts. The sewing machine is now the tool of my practice. The work manifests on canvas, which references painting, and the work also reminds me of quilting. There are parallel relationships between art hierarchies, recorded histories and social structures.

RL:Books are tactile, odoriferous things, are you happy for people to touch your work?Ӭ

SLJ:I don’t discourage them from touching, no. When people come to my studio, they say it smells like a library. I’m used to it, so I don’t notice it anymore.”¨

RL:Your compositions are very satisfying aesthetically.

SLJ:Yes, I am looking for that – the political nature of the work to be transformed into a tactile, visually pleasing object. The aesthetic appeal is a way to entice people in and spur conversation.

RL:There’s a similarity between the art gallery or museum and the encyclop3â„4dia – in their separation, categorisation and creation of context. Do you look for a particular political and social context in which to install your work?

SLJ:I want my work to be experienced in whatever space it’s shown. I had a show in a non-profit space in Oakland, and someone asked me if I felt that my work had reached a level that surpassed showing there. I said: “Not at all.” Oakland is a politically charged place; there was an interest in having my work there and people were willing to experience it —CCQ

Samuel Levi Jones is showing at The Arts Club in Mayfair, London from 13 April Р10 September 2016 samuellevijones.comӬtheartsclub.co.ukwedelart.com